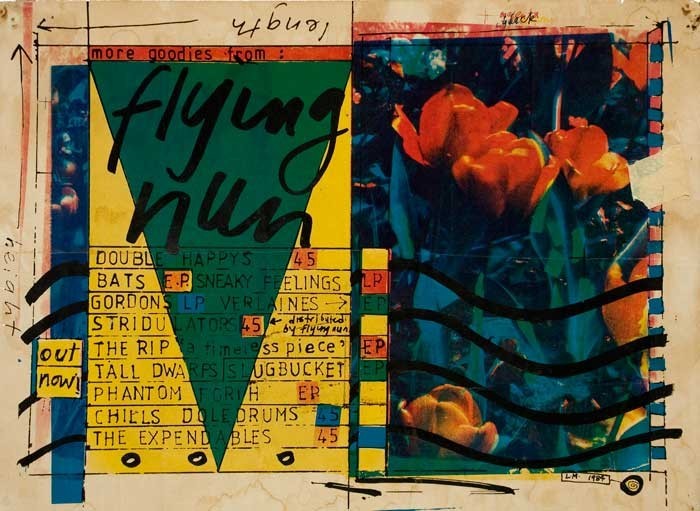

Artwork by Lesley Maclean

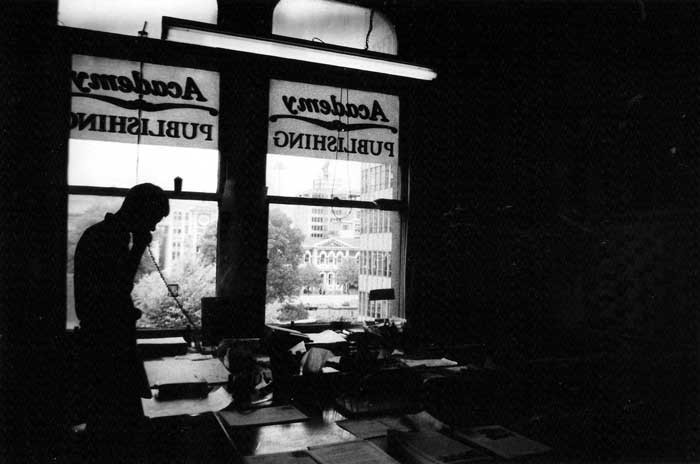

“The faithful know it’s there. Up a dusty timeworn staircase, two stories up in an ageing Queen St office block in Auckland’s central city. Behind the counter is former Look Blue Go Purple and current Olla drummer Lesley Paris. Behind her, through the open door of his office, I can see Roger Shepherd, Flying Nun Records boss and possibly the most non-showbiz record company executive in the industry.

“I’m sure Shepherd himself would cringe at being described so, but there’s no denying, that when he looked back on the first ten years of his label’s existence in September, he was looking back on achievement and innovation and more than a little chart success.

Roger Shepherd - photo by Alec Bathgate

“The part-time record label he started in Christchurch in 1981 is now one of the most successful in local music history. Some of its acts – Straitjacket Fits, The Clean, The Bats and The Verlaines – are either signed, or on the brink of signing to major international or big indie record labels. All tour successfully in America, Australia, Great Britain and some parts of Europe.”

Things were more of the moment when I wrote the above opening paragraphs to ‘Flying high on an alternative’ for the Christchurch Star in July 1991. In Auckland on job placement at Metro, I’d taken the opportunity to interview Roger Shepherd for a piece that celebrated Christchurch indie Flying Nun Records 10th anniversary. I’d been a label fan since my late teens and a professional writer for a few bare months.

When I told Metro editor Warwick Roger about the story soon afterwards, he said he’d love to run a feature on the label, but that I’d already missed the magazine’s long lead-in deadline. The Christchurch Star where I was stringing as a trainee journalist while studying at the University of Canterbury took the story and ran it in October 1991.

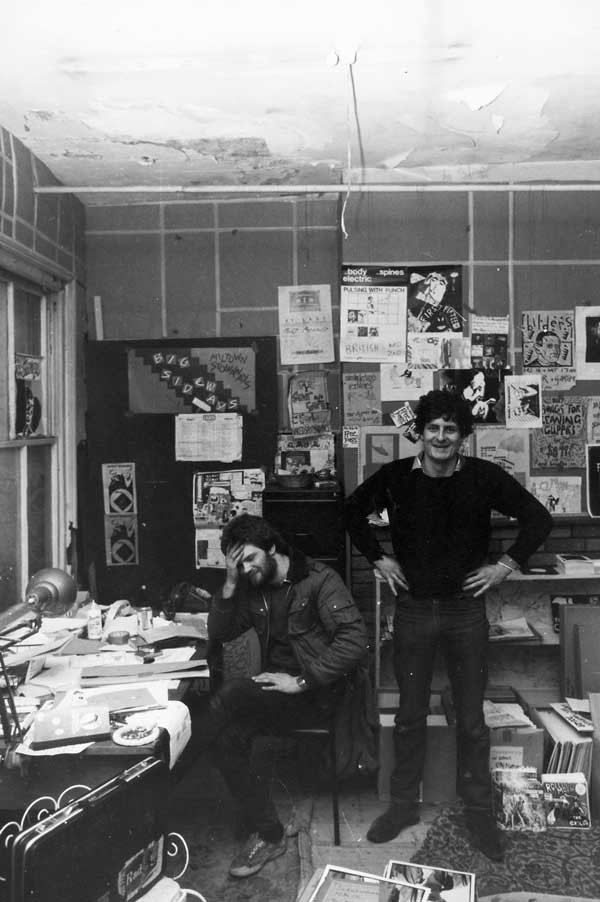

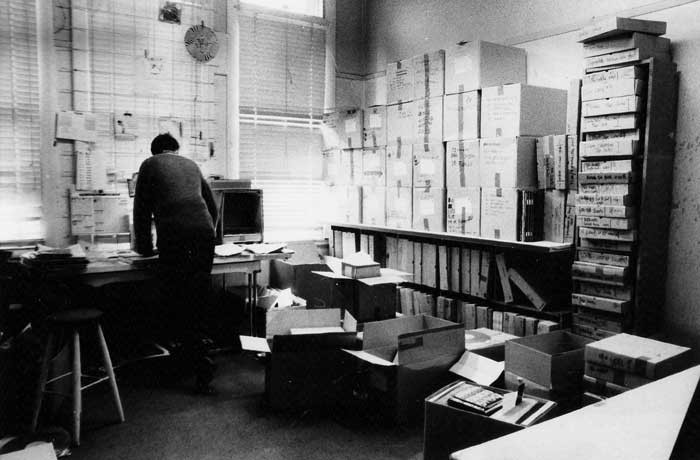

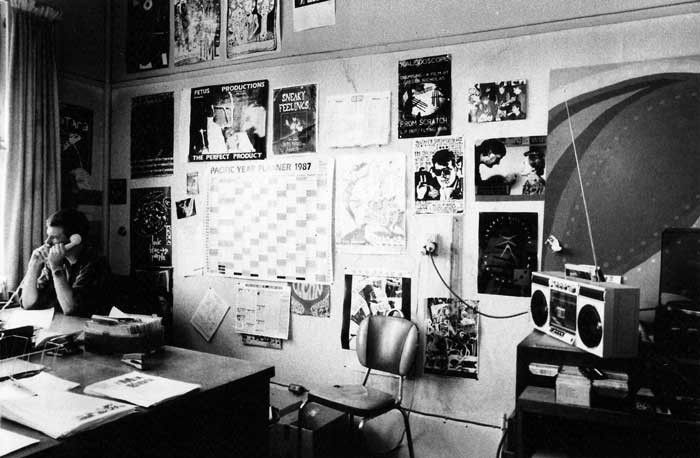

The Flying Nun office, The Dominion Building, The Square, Christchurch in the mid-1980s - photo by Alec Bathgate

Re-reading those words 25 years on, I see the expectation and aspiration the New Zealand post-punk community had for Flying Nun Records alongside an acceptance of the label’s gradual corporate embrace. The by-then well established tropes the Flying Nun community believed in and promoted are all onboard as well.

“There was all this great music happening. It was just good to record it and have the records as some sort of historical document,” Roger told me that day, noting the influence of early 1980s British independent record labels that had successfully (at least at first) bypassed the major record companies.

Roger Shepherd and Hamish Kilgour - photo by Alec Bathgate

“We were inspired by the punk and post-punk British bands that were being released, bands like Wire, the early Teardrop Explodes, Echo and the Bunnymen and the early Rough Trade releases. It was an exciting time musically,” he said.

The label’s move to Auckland in 1989 had been controversial, but as Shepherd explained: “We had to be that bit closer to markets and to the people who pressed our records. Auckland is also that little bit closer to the world. Some bands like Straitjacket Fits and The Chills are ambitious in what they want to do, and have gone after what they want to achieve, and in order to facilitate this, bands with track records are licensed to major record companies who have the dollars and cents to invest in a band. And that’s not just recording and airplay but marketing, touring and advertising a band properly. Touring somewhere like the US can be time consuming and expensive.”

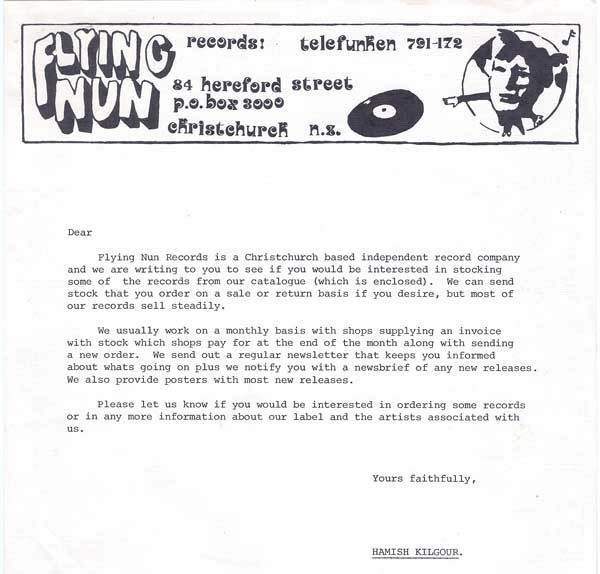

Hamish writes to retailers

Flying Nun retained control of what bands it signed and which records were released locally and in Australia, where they were distributed by Festival and Mushroom respectively. The economic climate meant that retailers were cutting back on the numbers of records being stocked. This made it harder for new bands to get exposure.

Shepherd had just returned from the influential New Music Seminar in New York, a vital forum for exposing music in the USA, and interest in New Zealand bands has never been higher. He took advantage of the trip to arrange distribution networks in Europe. Germany and Holland were outposts of New Zealand music fandom.

Typical of later reiterative tellings, I see now that I’d de-emphasised the label and era’s dark arty strand of The Gordons, Fetus Productions, The Pin Group, Phantom Forth, Marie & The Atom, Flak, Eight Living Legs, Naked Spots Dance, Children’s Hour, This Kind Of Punishment, Headless Chickens, S.P.U.D. and Skeptics in the piece in favour of the label’s ‘Dunedin Sound’ folk rock strand.

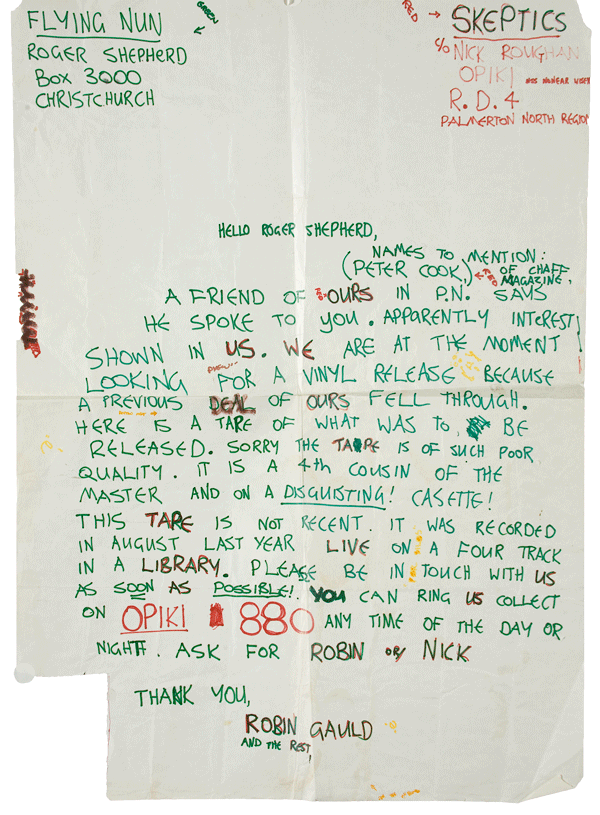

The Skeptics write to Roger Shepherd

A close reading of the records Flying Nun released between 1981 and 1986 shows nearly 40 percent came from Auckland acts, which I always put down to Chris Knox and Doug Hood’s influence. But the South Island groups were generally more accessible musically than the Auckland groups and survived longer.

I spoke to David Kilgour, Chris Knox and Martin Phillipps by phone for the 10-year anniversary piece and they were as open and articulate as I hoped they’d be.

“It [4-track recording] was practical at the time,” Chris Knox, one of the label’s key thinkers said, then noted the changing times. “But as Flying Nun have been able to get hold of more money, the pressure from Mushroom for higher production standards has come and things have changed. Back then it was for the sheer fun of recording with The Clean and being able to make records in your living room and seeing them in the shops.”

Knox had been a politicising agent on the emerging local scene. Based on his previous group Toy Love’s experience, he’d been quick to articulate dissatisfaction with major record labels, big recording studios and the traditional Australian tour slog. It was The Clean (as Knox suggests) who first fully seized the new possibilities.

In September 1981, Flying Nun Records had a shock hit with The Clean’s ‘Tally Ho’, the trio’s budget recorded debut single. Recorded on a simple 4-track, the record rose to No.19 in the charts and stayed in the Top 40 for nine weeks.

Shepherd described the band as awesome and felt they were never quite captured on record, but that it was their success that inspired Shayne Carter (Straitjacket Fits), Martin Phillipps (The Chills) and Graeme Downes (The Verlaines) to develop their talent.

‘Tally Ho’ was the first of the four Top 20 hits Flying Nun Records would have in 1981 and was only part of a brace of records Flying Nun released in that first year. The Christchurch music scene of the early 1980s was jumping and Shepherd drew heavily on it, releasing singles by The Pin Group, Mainly Spaniards, 25 Cents and The Builders. All are now collector’s items and that was something Shepherd has always fought against by trying, when economically possible, to keep all the label’s back catalogue in stock.

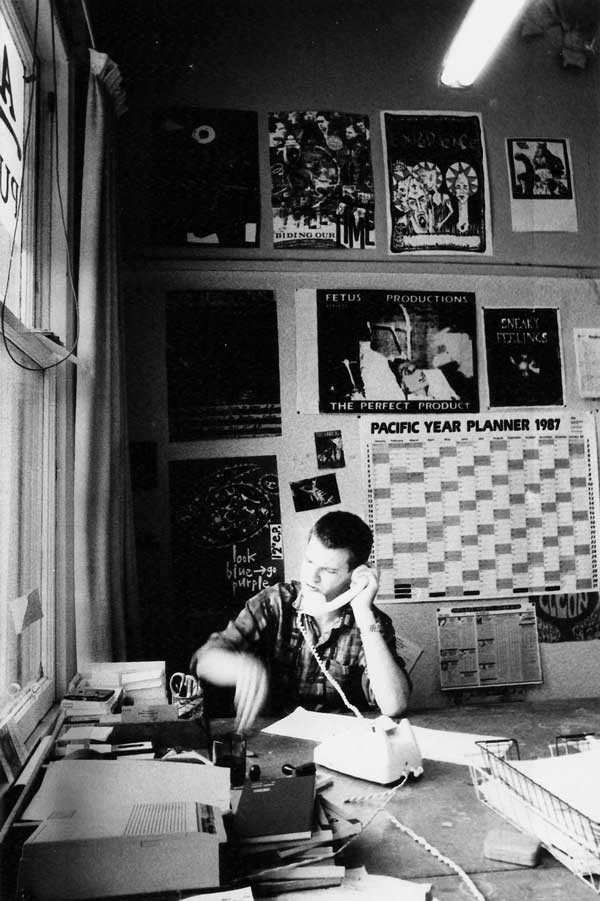

Designer Ian Dalziel in the Flying Nun office, The Dominion Building, The Square, Christchurch c.1985 - photo by Alec Bathgate

After The Clean and Toy Love the sound shouldn’t have been a surprise. But it was. The Chills had Martin Phillipps’ delightfully fey druggy pop. The Verlaines had the impassioned, almost overwrought Graeme Downes up front. There was the overtly 1960s strum of Sneaky Feelings while The Stones seemed to prefer the drone of The Velvet Underground and twisted minimalism of Wire.

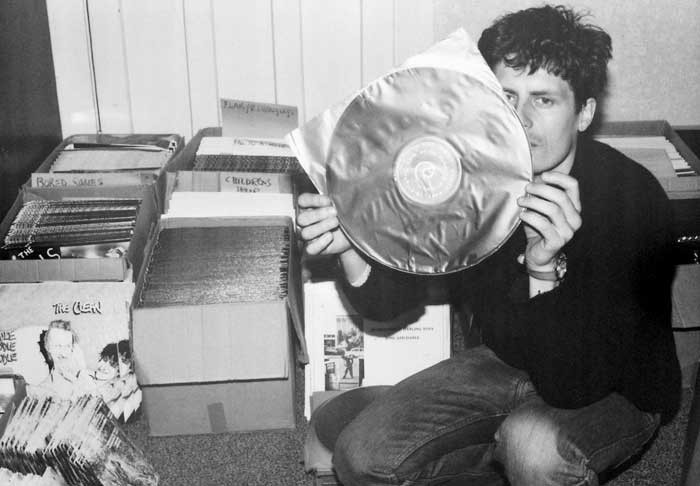

Hamish Kilgour in the Christchurch Flying Nun offices c.1984

In their wake came Look Blue Go Purple, The Bats, Dead Famous People, Jean Paul Sartre Experience, Goblin Mix, The Exploding Budgies, Able Tasmans, a rejuvenated Skeptics, Tall Dwarfs, Bird Nest Roys, Bailter Space, S.P.U.D, Doublehappys, The Great Unwashed, Headless Chickens, Children’s Hour, Straitjacket Fits and a number of one-offs.

The real difference from previous generations of local musicians was that many of the bands remained stubbornly based in New Zealand and made it a point of pride. It was an inward-looking perspective that while useful in cementing local identity also temporarily blinded them to their wider potential.

Roger Shepherd and Gary Cope in the Flying Nun offices in Gloucester St, Christchurch, 1987

America would prove to be the largest and most ongoing interest in New Zealand indie groups and anyone who had their records released or toured there seeded an enduring market for their music. But that took most by surprise even as late as 1991 when the full possibilities were still mustering.

The Clean reformed in 1988 and again the following year, releasing an epic album, Vehicle, then broke up. It was never intended as a permanent reformation and the band resumed their individual projects: drummer Hamish Kilgour with Playground (later The Mad Scene), bassist Robert Scott with The Bats and guitarist David Kilgour pursuing a solo path with backing band.

Kilgour still lived in Dunedin, Flying Nun’s spiritual home, when I spoke him in mid-1991. He proved refreshingly down to earth and seemed to have mixed feelings about the whole experience, stating, that at the time The Clean started recording with Flying Nun, there was no one else. The guitarist admitted that while in the early days touring overseas was a pipedream for the band, Toy Love’s experience in Australia had coloured the way they thought about going there.

“It meant more in the fact that we wouldn’t follow the Toy Love route and go to Australia and try to break through there. In the 1970s Australia was seen as the natural stepping-stone. Everyone did it. Split Enz, Dragon – we always thought we’d want to tour England or America.”

The label, its groups and their fans were no less enamoured of England than the early New Zealand punk and post-punk acts had been. Many went there as soon they could afford to in the mid to late 1980s. But with Australia now on the touring map and record release schedule that had well and truly changed. Flying Nun Records in 1991 was a large trading concern with 10 years’ worth of records and hits to its name.

They were a clannish bunch, the Flying Nun crowd. By the time I got to them for the Christchurch Star story, they were hunkered down like a robber band in the heart of New Zealand’s only real city. Among the assembled ranks that day was Paul McKessar, whom I vaguely knew from Hamilton.

Roger Shepherd in the Flying Nun offices, Christchurch 1987 - photo by Alec Bathgate

Like myself and many others, he was a provincial fan drawn into the excitement around the label and the music it enabled. McKessar would have first encountered the rising scene while steering the Waikato city’s “Flying Nun” band The Human Lawnmowers. Every population centre had a Flying Nun band. They were an important part of the picture. When the South Island groups toured north, sympathetic locals would often be the support act and a potential source of local organisation, accommodation and record buying and distribution.

No surprise then that many of the early Flying Nun Records fanzines came out of the less populated centres. Gisborne had Grant McDougall’s The Captain’s Fanzine, Nelson had Andrew Heal’s Whole Weird World and Hamilton had Ha Ha Ha, which predated them all.

That brings me to the second part of this story, that of Flying Nun Records as a national cultural movement around which many would build their identity in the coming years. You’ll find the historical facts – the dates, records, personnel and places – and some analysis of the label, its ongoing history and that of its groups and key players elsewhere on this site. But the story I want to tell next is more personal although not untypical. It’s the informed fan’s view from the outside looking in on a cultural phenomenon that is unfolding before their eyes and ears as they move slowly closer and closer to its centre.

The very act of buying the indie records and seeing the groups that sprouted from 1980 onwards in New Zealand was a statement of difference and of local confidence that many clearly needed.

The pop charts were an exciting part of that unfolding dynamic and available to all. Most of Flying Nun’s best records racked up significant public sales indicating a wide support base, tellingly for those groups who toured extensively and often.

Also important for provincial outliers was the label’s mail order service. Roger Shepherd and later Hamish Kilgour always slipped a letter into record orders. “Thanks for your cheque (much needed)! I suspect that you might find the High 30s Piano a bit rough, but the songs themselves are truly great. Hope you like it along with the other records. You’re right about shops in Hamilton. It’s very hard to get them to stock much of anything very interesting besides the few sure-fire records (Boodle etc),” Roger wrote me in mid-1982.

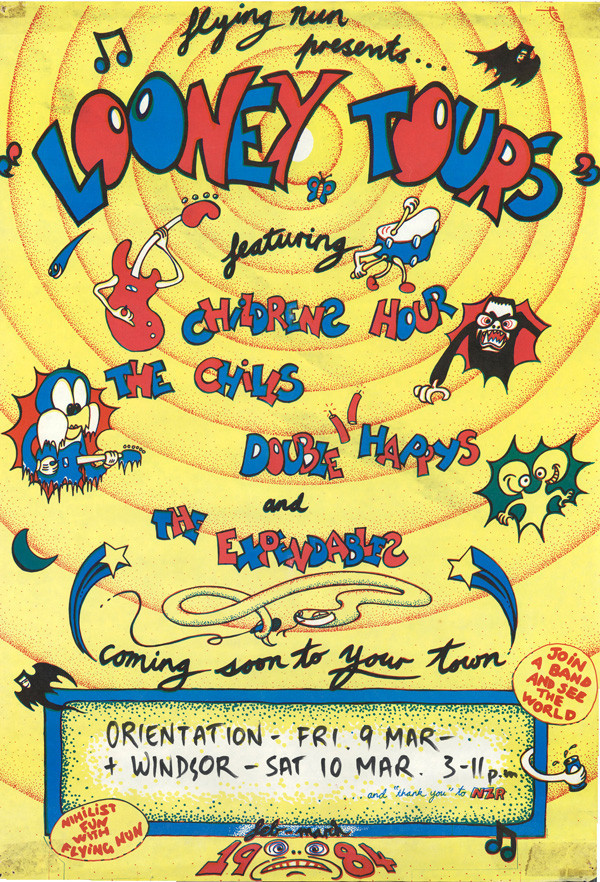

It wasn’t until early 1984 that the first Flying Nun Records bands arrived in Hamilton. The Great Unwashed appeared in late January and was chased soon after by a Looney Tour in early March. The first great package tour of the Flying Nun era was a surprise when it came. None of Looney Tours bands had released more than a handful of songs when The Chills, Children’s Hour, The Expendables and Doublehappys set out from Dunedin.

Aside from their timeless psych-pop tracks on the Dunedin Double compilation of 1982, The Chills had just one single out, ‘Rolling Moon’, backed with the burning psychedelic instrumental ‘Flamethrower’ and as-punk-as-they-got ‘Bite’. A Top 30 record for them in December 1982.

Brooding Auckland Birthday Party boys Children’s Hour (the future Headless Chickens) and Christchurch art-rockers The Expendables as They Were Expendable had one EP apiece – Flesh and Big Strain. Dunedin punk-pop brats Doublehappys had no records out at all. It was potential that drew us.

The audience at University of Waikato’s Wailing Bongo on 10 March 1984 was small, but that didn’t deter Doublehappys’ Shayne Carter and Wayne Elsey letting rip with sarcasm and a furious tuneful sound.

The Chills were slick. No sign of psychedelic or punk excess here. Martin Kean had replaced Terry Moore on bass and Peter Allison provided competent, but subdued keyboards as Alan Haig provided the relentless beat. Children’s Hour came on all dark and angry. They were a huge pregnant scowl of a band with sound to match. The Expendables had a sound beyond me then.

The bands retired afterwards to our four-bedroom “toilet” in a street opposite the Claudelands Showgrounds in Hamilton East. Someone had pot, bags of it, courtesy of a benevolent friend and we rolled numbers well into the early hours with Shayne Carter and Wayne Elsey as our flatmate Goochy distributed them in singlet and nylon shorts. In the tiny lounge The Chills’ Martin Phillipps strummed the soon-to-be released ‘Pink Frost’ on an acoustic guitar. Heaven.

Hamish Kilgour and Roger Shepherd in the Christchurch office of Flying Nun in early 1984 - photo by Stuart Page

My friends and followed the tour up to Auckland that weekend, crashing unannounced into Chris Knox and Doug Hood’s Summer St, Ponsonby home. Hood was there, as was Knox, who’d just become a father. They’d seen us outside debating who would knock on the door and thought it was the cops. Doug disappeared looking for a spliff, leaving Chris Knox to roll out the sarcy one-liners as he inked the dates on a pile of Netherworld Dancing Toys posters.

Doublehappys, who’d been recording in town that day, appeared with genial Children’s Hour bassist Grant Fell, who remembered us from Hamilton. They had a mix of the Doublehappys’ first single, which was superb, capturing Elsey’s whooping slide and world weary words and Carter’s chattering rhythm and peerless rock sneer.

In early May 1984, Bill Direen’s Builders arrived in Hamilton for a Left Bank Theatre show. The Verlaines followed in July. By then, the Waikato’s answer to the South Island groups had formed. There was only one group worth anything in the city in the early to mid-1980s. A snappy little guitar band called The Human Lawnmowers. The name came from a song on The MC5’s second album, Back In The USA, but their sound didn’t.

At their peak, The Human Lawnmowers were a VU influenced trio made up of Joe Flynn (guitar, vocals), Terry Edwards (drums) and Kent Ericksen (bass). Edwards and Flynn had played in a late version of The Accessories, a Hamilton mod band, who released two records – ‘The Accessory’ backed with ‘Friday Night’ in 1982 and the little-seen Spud and Veges 12” EP in 1983.

I was in the audience when The Human Lawnmowers played the Left Bank Theatre in November 1984. The three-piece was active on campus as well, playing with class Aussie act Hunters and Collectors in March 1985 at the Wailing Bongo. They were back the following month with Sneaky Feelings from Dunedin. There was a heckler in the crowd that night. “We’ve got your money,” Joe snapped, cutting him dead. He later struck up a strong rapport with the Sneakies’ David Pine.

Joe was a deep smart guy from Tokoroa. His parents were English. He was into The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, whose version of ‘She Said Yeah’ The Human Lawnmowers played.

By 1985 he’d developed a big thing for The Velvet Underground. The Human Lawnmowers played a whole set of VU tunes one show and a 20-minute ‘Sister Ray’ mono-riff wail-out another.

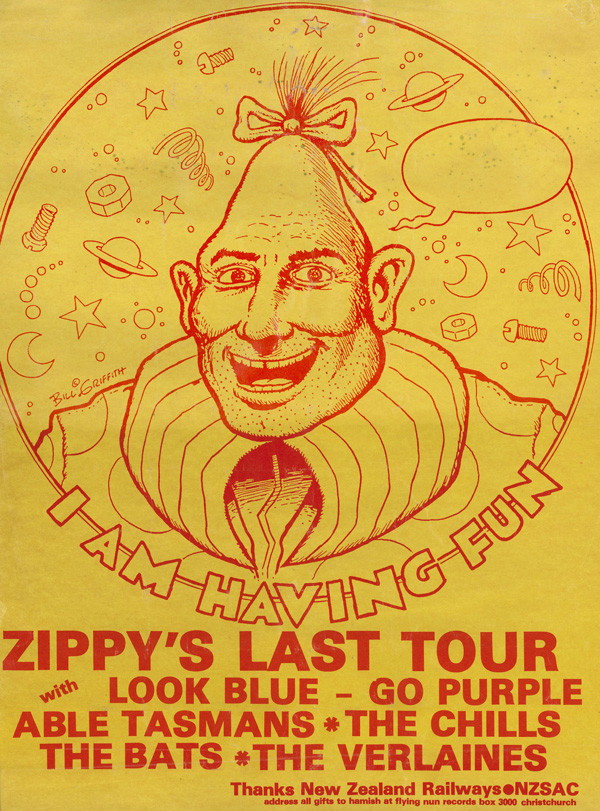

Orientation that year saw a second Flying Nun package show, Zippy’s Last Tour, arrive. It featured The Chills and Look Blue Go Purple, and they played at the Wailing Bongo on 4 March 1985. We were looking forward to seeing Look Blue Go Purple on the back of two tracks on the Songs from the Lowland compilation tape. They were the first all-women group on the scene since Marie & The Atom.

The Chills with Terry Moore back on bass had only released one single since their last visit. The okay ‘Doledrums’ backed with ‘Hidden Bay’ that climbed to No.12 in the pop charts in December 1984.

Martin Phillipps had some of his best years in the mid-1980s. Film from the era shows a fresh tight group with a packed set of organ driven folk and garage rockers. Terry Moore always lifted the songs up by playing a melody off of Phillipps’ guitar and the steady Germanic pulse of Alan Haig’s drums pumped them full of chill southern allure.

But little of that was ever caught on tape. There was only the promising Lost EP in 1985 and ultimately that was the problem. They’d been New Zealand’s most promising band for four years. “The Curse of The Chills”, Phillipps and keyboard player Peter Allison later called it.

In early 1985 my brother Gonzo finally purchased a car and we were in Auckland every second weekend trawling the record stores. I picked up REM’s Chronic Town EP at Sounds Unlimited in Newmarket at Joe’s request. He also recommended Fables Of The Reconstruction and Life’s Rich Pageant, which I duly bought.

We’d often linger afterwards in the city for shows at The Windsor Castle in Parnell, an early punk venue that was firing again. I’d never seen Toy Love live, and Tall Dwarfs, Alec Bathgate and Chris Knox’s studio project rarely played out so I jumped at the chance to catch them at the Windsor Castle on 6 April 1985 with Bird Nest Roys in support.

Tall Dwarfs opened with ‘Turning Brown And Torn In Two’, a menacing Knox tape loop and lyric with minimal accompaniment, then it was straight into ‘Shade For Today’, Alex Bathgate’s bleak folkie from Canned Music, before switching instruments again for ‘Beauty’; Knox to 12-string and Bathgate to bass.

Alec Bathgate was a revelation as he picked and chorded his way through the sinister eastern psych of ‘Clover’ and the feminist ‘Woman’. A long haired Mike Dooley, Toy Love’s drummer, joined them unannounced, rat tat tatting out a masterful ‘Maybe’ from Louie Likes His Daily Dip before going straight into an upbeat note sprinkled ‘Nothing’s Going To Happen’ powered by Dooley’s motorik drumming. ‘Gone To The Worms’, an old Toy Love tune was next, lumpy and lo fi. The trio would record the song for Tall Dwarfs’ first album – The Long And The Short Of It – their next release.

The tape loops were back for a fine ‘Brain That Wouldn’t Die’ and ‘The Crush’, both from Slug Bucket Hairy Breath Monster. “Graeme Jefferies,” a stooped Dickensian Knox urged and the stage filled with Jefferies, his brother Peter and Chris Matthews, all then playing in This Kind of Punishment, for a triple drum and guitar feedback strewn ending.

When I totalled Gonzo’s car during a work break our Windsor Castle excursions ceased. We skipped the Doublehappys show at Uncle Sam’s in Hamilton in mid-June 1985 because of it, one of only a few shows I regret missing. I picked up the newspaper a few weeks later and was shocked and saddened to see a small item reporting guitarist Wayne Elsey’s accidental death on the train back to Dunedin. The first real darkness in that enlightened movement.

I don’t remember seeing The Human Lawnmowers live again until April 1986 when they fronted before Hunters and Collectors at the Metropole at the north end of Hamilton’s main street. There’d only been Sneaky Feelings and Look Blue Go Purple’s Strawberry Sounds tour and Alpaca Brothers at the university that year and that was no longer enough.

My youngest brother Stu and I shifted south to Dunedin in May 1986. The omens had been good for the shift from the very first. On an initial exploratory earlier trip in 1986, I found a copy of issue five of Garage that had been left by a fellow fan in a phone booth in Wellington. A chance encounter that was a little spooky considering the music explored within was what was drawing us south. The first four issues had already been picked up from Auckland record shops or direct by mail. There would be one further magazine in 1986.

Garage was a compulsory read. It hit its straps around issue 3 and it became clear the first sustained attempt to chronicle the history of the punk and post-punk era in New Zealand was working. It focused primarily on Dunedin and the Flying Nun Records roster, but coupled that with a rough construction of musical antecedents from indigenous punk and an acceptable lineage of musical outsiders, including The Go Betweens, The Cramps and Jesus and Mary Chain and casualties such as Roky Erickson and Alex Chilton.

It proved a compelling mix. Editor and principal writer Richard Langston’s curiosity was in accord and a little ahead of the time.

It was possible then for records to appear and go with not much more than an advertisement, a mention in the rumours column, and a review in RipItUp. If the group had some profile and was still going, a small feature somewhere was possible, but disbanded groups with retrospective records such as The Clean, Bored Games and Victor Dimisich Band had fascinating backstories that often went untold.

Garage answered questions that the lack of media piqued. It gave space to creative voices that up until then had been little heard. It gave them context. In it you find Martin Phillipps comparing the Empire Tavern to a folk club – its denizens wrapped warm and cozy against the cold indifferent world outside – and Richard Langston watching as a busy Chris Knox distributed records in Auckland and later crashed through a plate glass window as Headless Chickens played.

The Kilgour brothers talked in revealing detail about their large body of songs and recordings. Peter Gutteridge spoke. Shayne Carter did likewise on the gestation and recording of ‘Randolph’s Coming Home’. Bruce Russell and David Swift reported on The Bats and The Chills in London. Bill Direen checked in for words about Conch3.

There were fascinating snippets of information such as the sales figures for Dunedin records in Dunedin and a blow by blow making of a Doublehappys video. Indie rock’s mid-1980s musical depth is revealed through introductions to Goblin Mix, George Henderson, Peter Stapleton, Roy Montgomery, Andrew Brough, Alpaca Brothers, Bird Nest Roys, The Rip and Look Blue Go Purple together with live reviews of newer emerging groups. Dunedin was busy with music and would remain so well into the 1990s.

The downside was Garage could at times be annoyingly exclusive, dismissively reporting The Clean as having sold six and half thousand copies of Boodle Boodle Boodle in “Squarehead, New Zealand”.

Wait a minute, New Zealanders bought six and a half thousand copies of Boodle up to 1986!!? I always knew The Clean’s appeal was wide. You found their records in the most unexpected places and reunion show audiences were never uniform. But even that tells you something. Garage was political. It was concerned with the politics of creating culture and identity in New Zealand. There is plenty of pointed opinion and a real desire to define or at least examine a sense of place and identity in the many interviews.

Garage also recognised that indie culture had an international context. That it belonged to a wider movement. That’s why the fanzine carried reviews of British indie pop groups The Shop Assistants, Primal Scream, The Weather Prophets, The Mighty Lemon Drops and The Servants and US post-hardcore talent such as Sonic Youth, Scratch Acid and The Meat Puppets. All groups we read about in NME.

I must have written Joe Flynn a letter from Dunedin because he turned up at Harbour Terrace one day for a few hours. The Human Lawnmowers had planned a South Island tour that had fallen through, but Joe had come anyway.

The Human Lawnmowers had been playing quite a bit up north in Auckland and Hamilton. Paul McKessar was managing them and arranging shows with Hunters and Collectors, Battling Strings, Insect and The Pterodactyls, at The Galaxy, The Rising Sun and Windsor Castle in Auckland in April through July.

The group had a few good originals by then, including ‘Razorblade Rosie’, which appeared belatedly on the Surf Music tape in the early 1990’s and ‘Damn Sure You’re On Drugs’ and ‘Fading Light’, but an attempt to record an EP for Flying Nun with The Chills’ Terry Moore was unsuccessful. When The Human Lawnmowers van and gear was stolen in Hamilton soon after, the group were gutted and never fully recovered.

In 1993, I got the chance to write up that southern move for Metro as the opening essay in a series called my best year yet.

“I’d spent the empty early summer dreaming to the words of Hunter S Thompson and Kerouac against a soundtrack of mid-period Flying Nun, Hüsker Dü, Love and Sonic Youth. Dreaming, thinking that all the roads through Paeroa lead out, and feeling very alone,” I wrote.

“My best friend Ray and youngest brother Stu were living in Dunedin, distant tempting Dunedin, flush with the country’s best bands and mystical venues like the Empire Tavern and Chippendale House, all fragments glimpsed through the stilted world of record inner sleeves and RipItUp rumours columns.”

I must have been still in the midst of it all mentally because I unconsciously rolled the first Dunedin stay in 1986 into another in mid early 1987. An old Paeroa friend came along for the second ride. “It was fun to take him along to the Oriental and the Empire to see all those wonderful Dunedin bands, when all he’d grown up on was a diet of tired cover bands and hippie outfits,” I wrote, then asked who remembered “The Orange and those neat 1960s kissed pop songs? What about Bird Nest Roys? It’s still one of the best gigs I’ve ever seen – that warm happy feeling they gave out and those slightly shambolic riffy tunes.

“We were all still Flying Nun groupies then. At the end of each day we’d sit around and run through the musicians we’d seen. Kathy Bull inside EMI, David Kilgour shyly strolling through the Octagon and Peter Jefferies just up the road in Evans Street.”

In mid-1987, I headed home to Paeroa, exhausted and ill. Stu followed at the end of the year. He was still amped up by the string of shows he’d seen before leaving, involving Snapper, Stephen, Trash, Tall Dwarfs, Jean Paul Sartre Experience, Straitjacket Fits, The Terminals, The Dead C, The Puddle, Goblin Mix, Mr Big Nose and Look Blue Go Purple.

I thought Dunedin had peaked, but it was only pausing. The city fair bristled with venues, including The Oriental Tavern, The Burgundy Bar, art space Chippendale House and the trusty Empire Tavern, where great groups were playing weekly.

Stu and I headed back to Hamilton for university in early 1988, a year that would offer only an occasional cameo and gem such as Headless Chickens with NRA at the Hillcrest Tavern and The Cake Kitchen at the Left Bank Theatre. The river city had a small local scene as well that included Watershed and Frybrain.

Straitjacket Fits could be forgiven for thinking that they were being stalked in the late 1980s. We saw all their early shows in Dunedin and now I was standing in the Garden Bar of the Golconda Tavern in Coromandel in early January 1989 waiting for the Fits to appear.

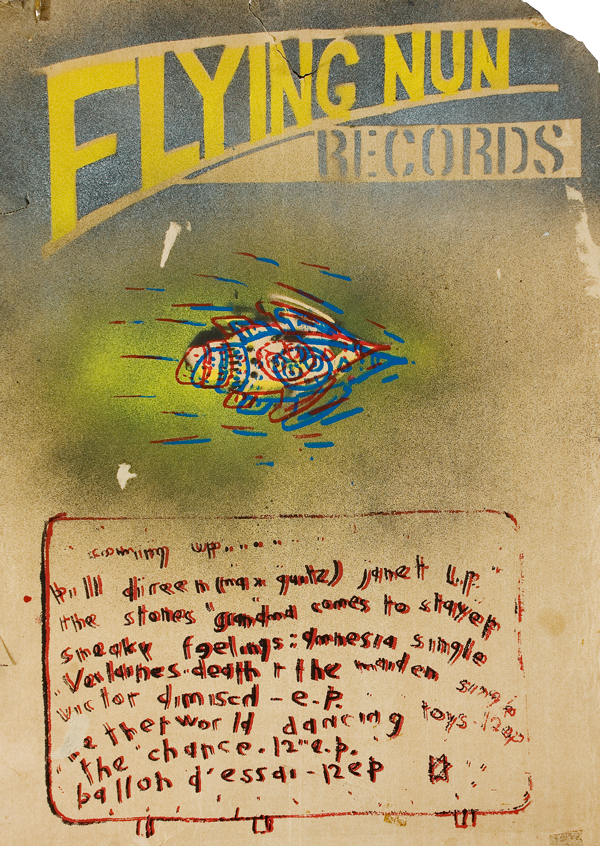

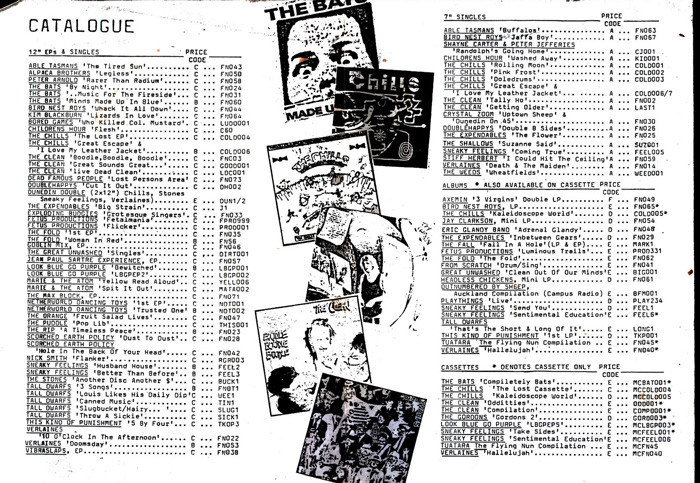

The 1987 Flying Nun catalogue

Two weeks on, Sonic Youth were in town for their first New Zealand show at the Powerstation supported by S.P.U.D. and The Verlaines. Daydream Nation, their breakthrough double album, had just come out. It’s predecessor, Sister, one of the defining albums of the 1980s had been released in New Zealand on Flying Nun Records and it seemed half of Paeroa was at the show together with everyone we knew from Hamilton and Auckland.

Back home in late 1990 after graduation, I applied for a place on the journalism programme at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch using a copy of Ha Ha Ha, which Stu and I had reactivated in 1989, and got in. As soon as I had the chance, I started writing about Flying Nun Records and the bands it released.

Truth be told, like many early followers, I felt the label’s heyday was over and had been for a while and despite a resurgence of second or third wind groups and the release of some of the label’s best albums in the late 1980s and early 1990s, our attention had shifted to Xpressway and the American music underground. But I remained as always, a critical fan, with a high degree of expectation, based on the standards the groups and label set early on.

Those groups and that indie label are still a central topic of conversation when I meet up with those that I shared the adventure of the 1980’s and 1990’s with. Many of the early records still sit in my collection and I’ll always make time to read what the central players have to say. Flying Nun Records, and that wide, welcoming community who fostered the label and its bands, coloured my life and outlook for good. It helped determine the path I took. Roger Shepherd, Doug Hood, Chris Knox, the brothers Kilgour, Martin Phillipps, Graeme Downes, Peter Jefferies and all the rest, my parents would like to have a word with you about that.

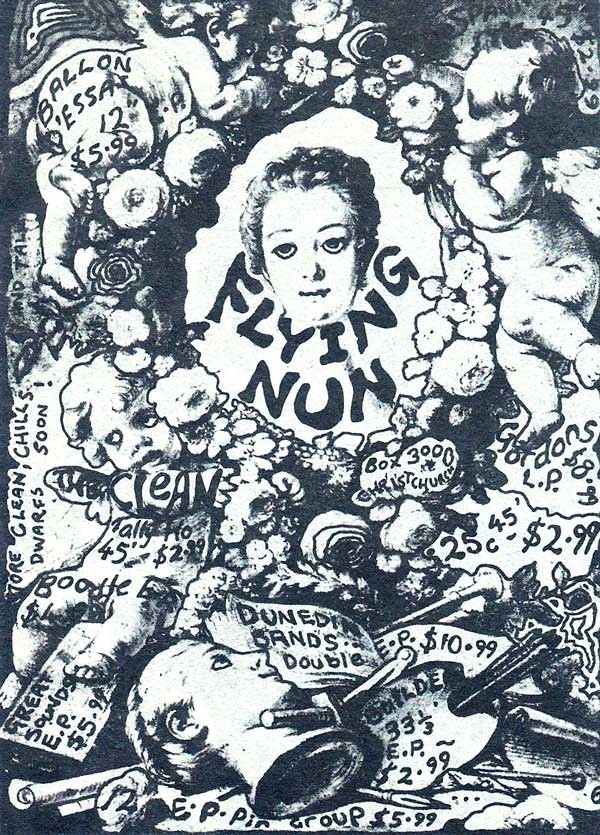

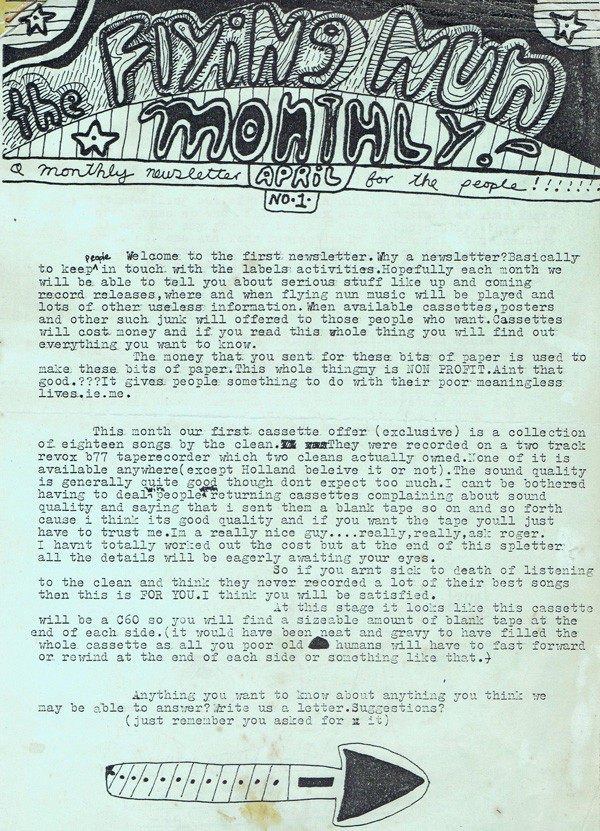

The first Flying Nun newsletter, April 1983

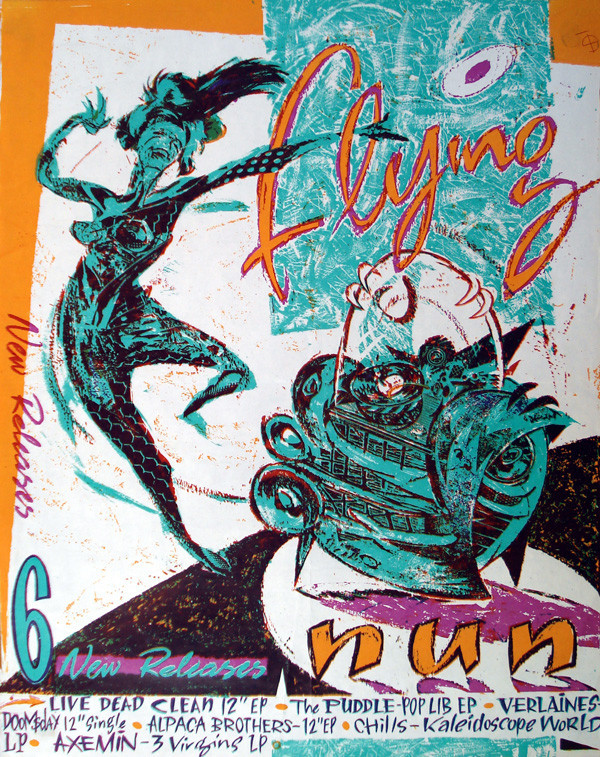

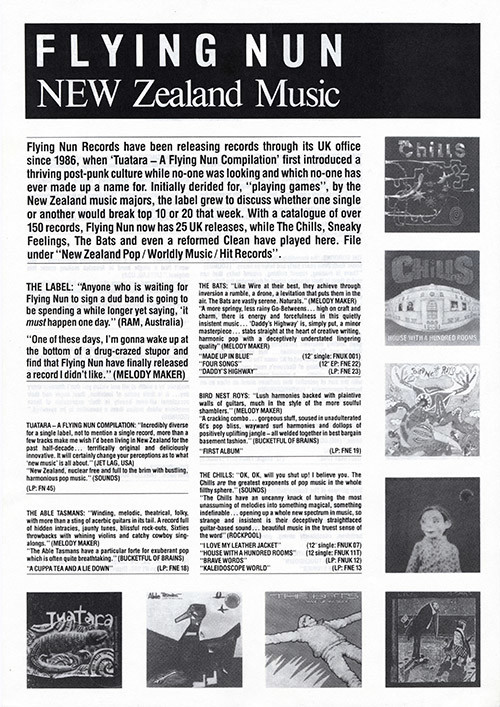

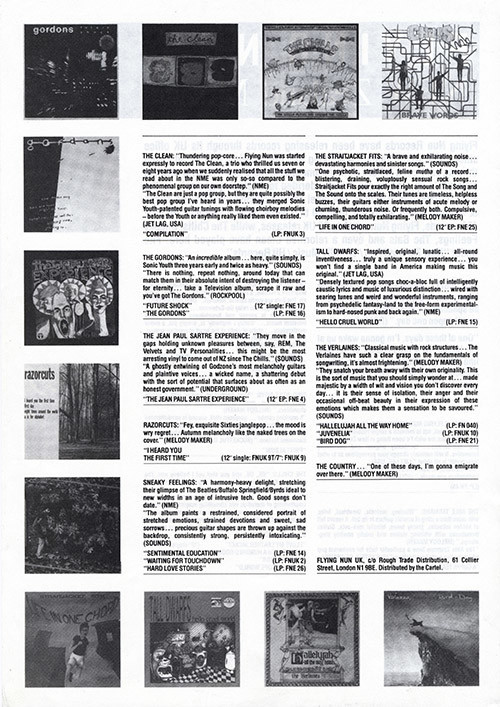

A Flying Nun Europe PR flyer issued by Rough Trade in 1989 - Simon Grigg collection