“You see I grew up in a brown neighbourhood

I learnt a few lessons like a white brother should

about the struggle that goes on and on and on

to be treated equal, because all hatred’s wrong.”

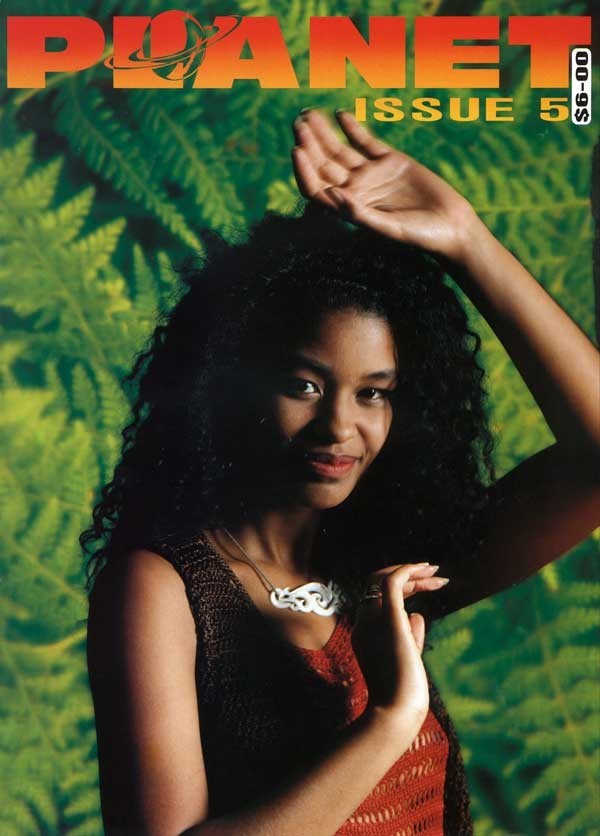

‘Colourblind’ – Matty J and the Soul Syndicate

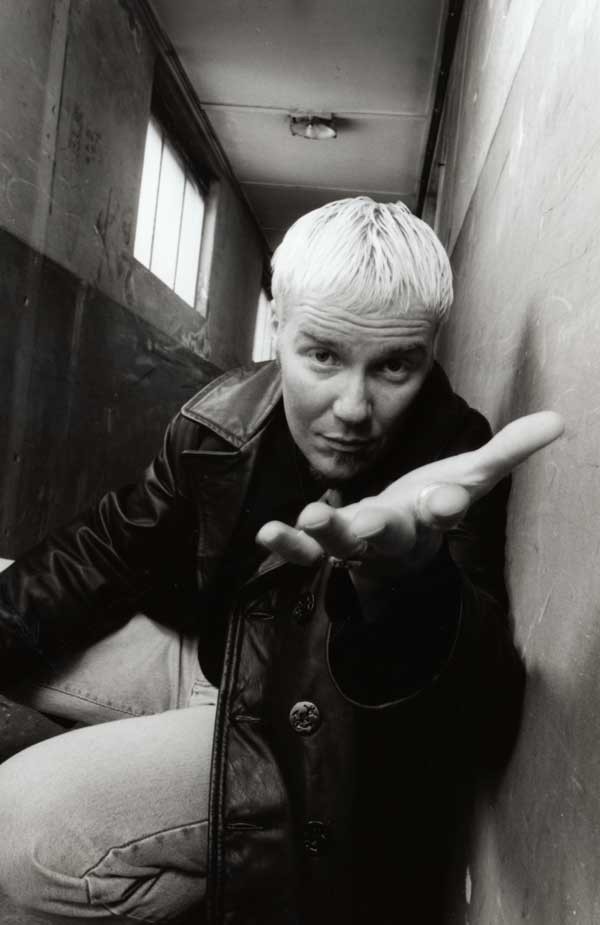

Matty J’s the guy in the blue denim dungarees behind the counter of Truetone Records in the Manukau City Centre rapping quietly with two beanie-wearing South Auckland homeboys about the latest dance sounds. The guy with the solid gold earring and the merest hint of a beard. He’s four days away from the release of his new swingbeat single ‘Colourblind’, a soulful dance track that draws on his experience of growing up in South Auckland and his love of black dance music.

Matty J and The Soul Syndicate

‘Colourblind’ is part of an explosion of Auckland dance and groove music edging its way onto the city’s more progressive radio stations and record shops, a local musical flowering of the large Auckland dance subculture, which draws its inspiration and style from black urban dance music and its identity from the culture of the performer.

Dance culture didn’t spring up overnight, nor is it limited solely to young Māori or Polynesians from South Auckland.

Dance culture didn’t spring up overnight, nor is it limited solely to young Māori or Polynesians from South Auckland. You’ll find just as many white, middle-class, inner-city types getting down with it, and smaller scenes have developed in parts of Auckland like Avondale where rap/ hip hop outfit 3 The Hard Way hold sway. It’s a youth subculture that’s pulling racial barriers down, not by assimilation, but by respect for the uniqueness of different cultural groups.

Matty J Ruys grew up white in a brown neighbourhood. When his parents [his father is Dutch and his mother is English] arrived from Australia in the late 1960s they settled in Bader Drive, a state house street in Mangere. The young Matty attended school with the sons and daughters of two earlier waves of urban immigrants: Māori drawn to the city in the 1950s, attracted by work at the Southdown and Westfield freezing works and in the developing industrial areas of South Auckland, and Pacific Island families seeking employment in the booming 1960s and early 1970s. His ears pricked early to the wealth of black American sounds finding favour among the kids of South Auckland, and Stevie Wonder and The Jackson Five were early favourites.

On Matty’s eighth birthday the Ruys shifted to Otangarei, a mainly Māori suburb of Whangarei where one day, while crossing his primary school field, he was set upon by a gang of Māori youths and beaten. The attack left him suffering almost daily from epilepsy for seven years, but it didn’t make him a bigot and his respect for Māori culture remained high. And you’d still find him and his mates, with their squares of vinyl down, practising their break dance moves to the Sugarhill Gang, Grandmaster Flash’s ‘The Message’ and Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Buffalo Girls’. In tune with the times he appropriated a street name from a fave Herbie Hancock tune, “Rocket”.

When he graduated from Tikipunga High School he was presented with a tongue-in-cheek award for the school’s best Māori/ Pākehā.

After school, Matty moved into mime and acting and changed location to Tauranga where he appeared in stage musicals, including one more in tune with his roots. Fight The Power was a hip hop musical which played to large crowds throughout New Zealand.

Matty J

Matty’s big break, however, came from the most unlikely of places – a Valentine’s Day special edition of Blind Date on which he sang the questions to the woman contestants. He was spotted by the Strawpeople’s Mark Tierney and subsequently sang backing and lead vocals on the 1993 World Service album.

More vocal work followed with Annie Crummer, Hinewehi Mohi, Moana and The Moahunters and House Party. Matty had also linked with former Coconut Rough and Street Talk keyboard player and composer Stuart Pearce to begin his own project, Matty J and the Soul Syndicate.

He finally returned to South Auckland in 1992 and secured a job at Truetone Records where he put his enthusiasm and knowledge of dance music to good use, importing the latest dance discs from overseas.

He has mana among the area’s young brown population, but it’s not instant mana. “When you meet new people, it’s ‘who are you, who do you think you are, where do you come from?’” he says. “The respect comes from living out here and being a part of the life. You get no respect unless you have an understanding of the people and where they come from. You’ve got to listen, not just talk, and have a love for the culture, food and the people.”

Dance music in South Auckland attracts a young crowd and draws heavily on American rap for its sound, style, attitude and role models. The words and sounds of the urban American black underclass speak directly to the kids. Black American-dominated sports, especially basketball, are also popular.

They have a lot in common: dark skins, low socio-economic status, aging near-identikit housing, young populations at risk from crime and unemployment, and societies dominated by a white ruling class. That the cool SA sounds are black and the clothing of its adherents an imitation of black American street wear says more about recognition of the similarity than slavish imitation. Among the area’s Samoan teenagers there is an additional stream of influence from American Samoa and the substantial Samoan expatriate population in California.

There’s also a downside. South Auckland youth gangs have adopted LA gang monikers like the Crips, Bloods and Ghetto Boys. Matty J describes South Auckland as “a smaller, less-populated South Central,” the mainly black area of Los Angeles torn by gang violence and drugs – but also home to some hot rap acts.

In spite of its popularity, there are few places in South Auckland for contemporary dance music fans to get together, and as a consequence, the movement is mainly underground, with enterprising fans hiring local halls and booking DJs and live rap acts like Radio Backstab, MC Slam and DJ Jam and the Pacifican Descendants.

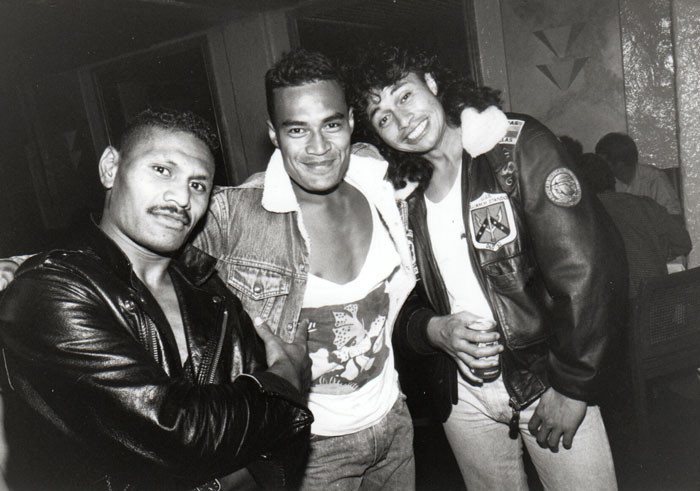

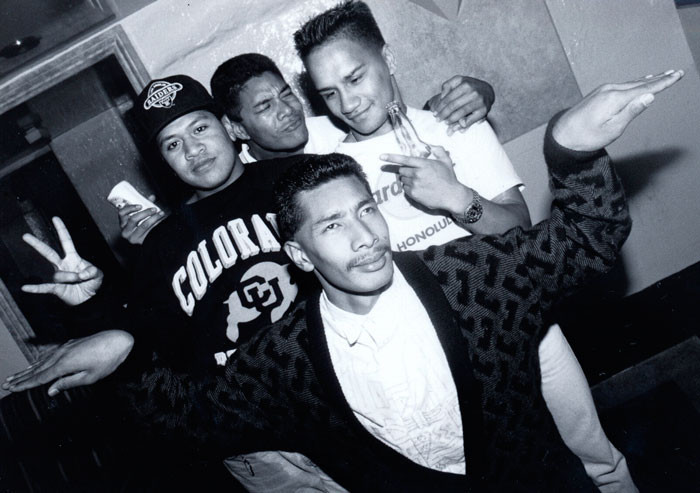

Pacifican Descendants

Nightclubs generally don’t cut it, but The Duke of Wellington Tavern in Mount Wellington and the New Soul Cafe in the Mid City complex off Queen Street are favoured out-of-area hangouts.

It’s not the music that instantly hits, however, it’s the dress. Around the corner from Truetone Records is Blitz, South Auckland’s major streetwear outlet. The clothes there aren’t cheap – it can cost up to $800 for a complete outfit. Throw in a Discman or Walkman, and the price tag for cool surpasses a grand. But price doesn’t deter. Fans will do without, scrimp and save to buy the latest Starter jacket, Vans, Airwalk and Fila trainers, 26 Red, Split, Mooks, Mossimo or Stussy shirts or vests and Workshop or Levis jeans.

Then there are the ever-present NBA caps, a colourful pork pie hat and coloured granny glasses or shades made popular by black groups like De La Soul and Arrested Development.

The clothes are so highly prized, some fans will just take them from others, and assaults for street wear aren’t unknown.

Behind the Blitz counter Eddie Wright is looking sharp in the latest streetwear and rapping keenly about acid jazz – the danceable jazz/ funk hybrid that has quickly gained favour among one section of the city’s dance community. With his little beard and bead-adorned Split shirt, he looks like a modern version of a 1950s beat bard.

Blitz has been open for a year, and despite the recession, trade has been good. Most of the brands popular with the dance culture are from overseas, aided by tariff-free importing, which has made offshore fashion quickly and more cheaply available. Two local brands, however – Workshop and Zeal – are deemed to be worthy of inclusion in any cool wardrobe.

Established two years ago, Zeal tapped directly into New Zealand and worldwide youth culture for clothing ideas. That’s not just dance culture, but surfing, skating and snowboarding. The label also looks back at styles from the 1960s and 1970s, with the new range of 50s-styled casino shirts harking back to the smooth styles made popular by Italian doo-wop groups and teen idols like Dion. For young women, the Zeal Babe label currently includes neon 1970s-look flares and laced side hip pants. By taking the best bits from older youth cultures and leaving out the embarrassing excesses, Zeal has lines that look neat in the 1990s and are surprisingly undated. With popular clothing lines in the youth market changing as quickly as fave dance songs, Zeal has fresh designs in the shops every 12 weeks.

New off the racks this season is Rave wear, the “Manchester look” popularised by that city’s white dance bands New Order, the now-defunct Happy Mondays and the Stone Roses, and a line of clothing influenced by the worldwide economic recession.

Recessionary clothing became popular as more and more young people joined dole queues or went to tertiary training. In both cases they had less money in their pockets, and the age-old op-shopping ritual became less a giggle and more a necessity, but the desire to look good didn’t dim. Suddenly old styles and fashions became popular again as adventurous but poor dressers hit the streets. Cue platform shoes, clogs and flares. The former lepers of fashion history now feature on a trendy stepper near you.

The pinched economic times also prompted a demand for cheap, hard-wearing clothing that looked good, and that’s when clothing companies like Zeal stepped in to manufacture items like denim railway shunters’ jackets and wide-leg jeans. Now, having reaching a sales peak in New Zealand, what one of the partners describes as “a commercial cottage industry” is expanding into Australia.

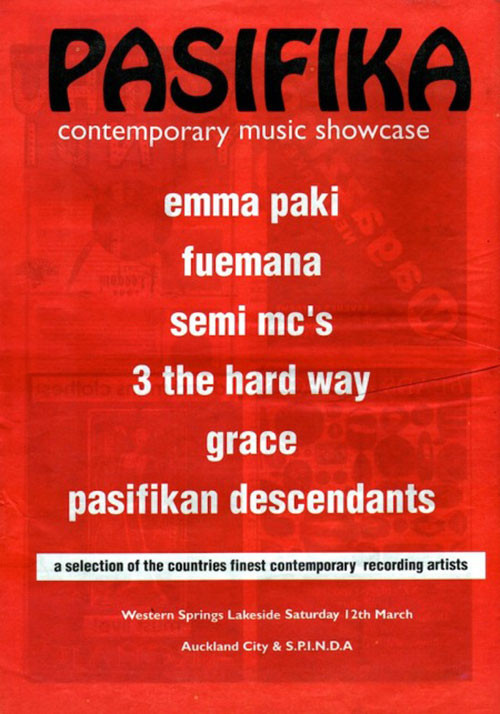

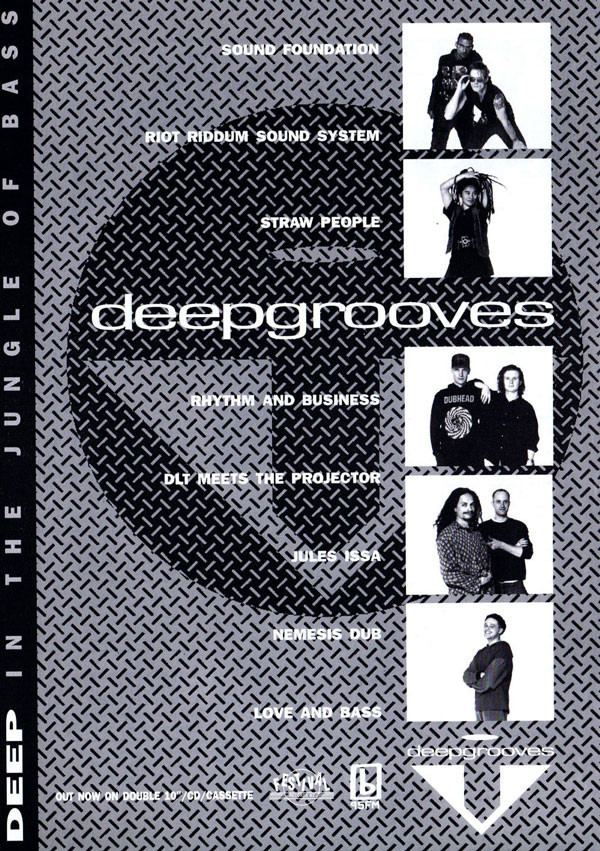

Tapping the same market, but the musical vein, is Auckland dance music label Deepgrooves, which recently set up a Sydney branch to break its roster of acts in Australia.

The advert for Deepgrooves Records first compilation, a double 10-inch

Label boss Kane Massey is one of a number of young Aucklanders revitalising local music by dipping into the city’s well of brown talent. He joins longtime black music fan Murray Cammick’s Southside Records, home to Māori chart act Moana and The Moahunters; newcomer Tangata Records includes Emma Paki and Gifted And Brown among its acts; and Pagan Records has dance mistress Merenia on board. Even Flying Nun Records, one of the last New Zealand bastions of three-chord pop and white guitar noise rock, has the very danceable Headless Chickens.

Deepgrooves releases cover the whole dance music spectrum from the High Street hip hop of Urban Disturbance and old school rap of 3 The Hard Way through the acid jazz of Cause Celebre regulars Freebass to the jaunty reggae of the Mighty Asterix and Jules Issa.

Freebass in Auckland's High Street, 1992. Left to right: Steve Harrop, his brother Ben, Ritchie Campbell, Ben Holmes, Nathan Haines, Juan Muzzio and Ben Gilgan - Photo by Alistair Guthrie/Simon Grigg collection.

Freebass at Cause Celebre

Around 1993, musicians included Nathan Haines, Joel Haines, Ben Harrop, Steve Harrop, Ben Holmes, Ritchie Campbell and Zane Lowe.

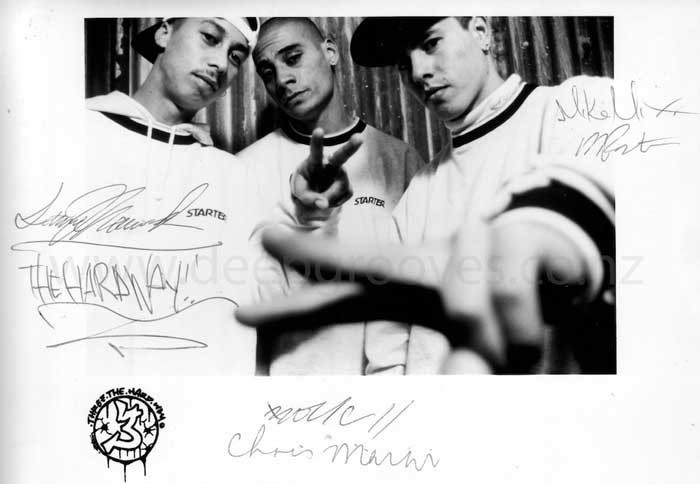

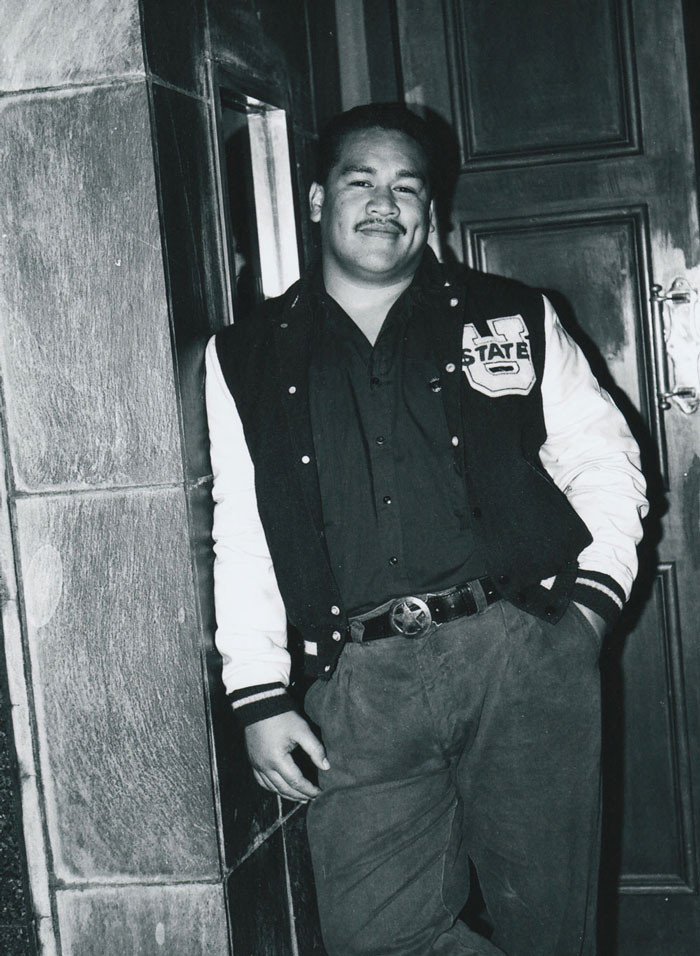

3 The Hard Way are a young street smart hip hop crew from Avondale. As their first release tells it, they’re “straight from the old school” of rap.

Their members have spent time in early Auckland rappers Total Effect, BB3 and Chain Gang, but it’s 3 The Hard Way now and the sounds and name fit just so. They’re West Auckland homeboys, they grew up there, and that experience is in the music – the early chaotic days listening to older brothers’ reggae, George Clinton, hard funk and early rap, cobbling together equipment from old Technics stereos, learning their sounds from DJ friends Nick Roy and John Petueli.

“The words are about what we’ve been through,” says rapper Boy C (Chris Maiai). “About how hard it was to get into the music. ‘When we first started we didn’t know anyone,” adds DJ Mike Mix (Mike Patton).

3 The Hard Way

First up from 3 The Hard Way is ‘Hip Hop Holiday’, a song based around a sample of 10CC’s ‘Dreadlock Holiday’. The sounds are hard, thanks to some assured DJing from Mike Mix and DJ Damage (Lance Manuel), but not so hard that a chart hit is out of the question. That’s fine with the band, they haven’t compromised the music they want to make, and they want as many people to hear the music as possible. Next up is a hip-hop version of Jimmy Cliff’s ‘Many Rivers To Cross’ to be followed by a song for their kids – Boy C and DJ Damage both have young sons.

It’s taken 3 The Hard Way a while to get into the studio, so now they’re not wasting any time. New Zealand On Air has proved that its ears aren’t too far from the street and has stumped up two recording grants and a video grant. And what 3 The Hard Way learn about recording, playing live and putting out records will stay in West Auckland. Part of the plan is to record and encourage other local outfits still struggling away in garages, moulding their sounds.

Talking to these three, it’s easy to know why dance music is the street buzz of the moment. Like the best new movements, it’s grown out of an underground scene and is propelled by young people jacked up on the sounds, but singing and rapping about their environments to an audience that can relate directly to those concerns and experiences. To borrow a phrase from black soul label Motown, it’s the sound of young brown Auckland, and it’s a new voice that’s seldom been heard here. With the swelling young Māori and Polynesian population rising in the city, there’ll be plenty of ears keen to hear songs that reflect their worlds.

Chances are those same ears will be tuned to Mai FM or bFM’s specialist dance music shows. Despite some criticism that it’s too conservative and lacks an ear for harder dance sounds, the Ngāti Whātua-owned Mai FM is a vibrant addition to the city’s otherwise ossified airwaves. It’s up, comfortable with its format, and spot-on with its audience.

Mai sales and marketing manager Vivien Bridgwater says the station is listened to by one third of Auckland teenagers under 19, with young Māori and Polynesians most strongly featured. It’s an audience long ignored by most Auckland radio stations. “Radio Hauraki knew it had a large Māori listenership because of the number of calls it got from South Auckland,” she explains. Good for the ratings, no doubt, but hardly pleasing to advertisers looking for listeners with loose bucks in their pockets.

Mai FM, however, draws its listeners from a wider group: young urban dwellers, many of whom lack their parents’ weighty antipathy toward things Māori.

Mesh at bFM's 1994 Summer Series in Albert Park. Mesh were one of the first bands to blend Pasifika with electronic technology, mixing traditional sounds and instruments with synths.

Meanwhile, up the hill and over Albert Park, bFM is still bursting from the airwaves with fresh sounds, some of the most inventive ads on air and that peculiar arrogance of young people still two steps away from the full-time workforce with half a degree in their back pocket.

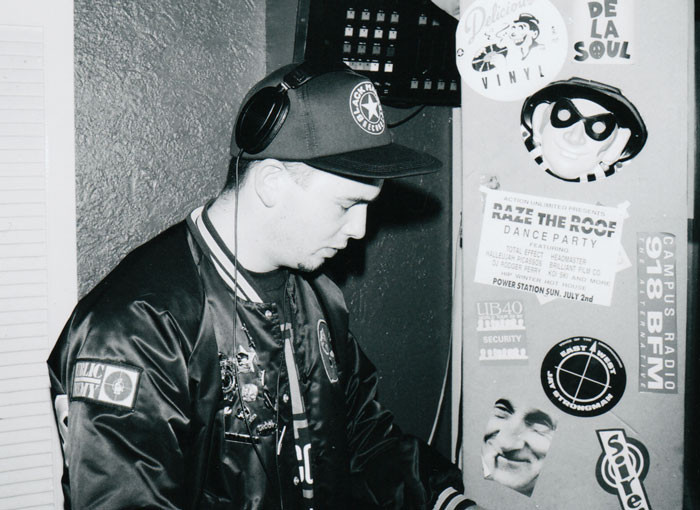

Programme director Graeme Hill puts the station’s dance content to the left of Mai’s, with harder-edged acts like Cypress Hill, Ice T and Body Count featuring. Local dance acts feature liberally in both the general playlist and on Freak The Sheep – the station’s well-regarded New Zealand music show which combines up-to-date releases with information and interviews.

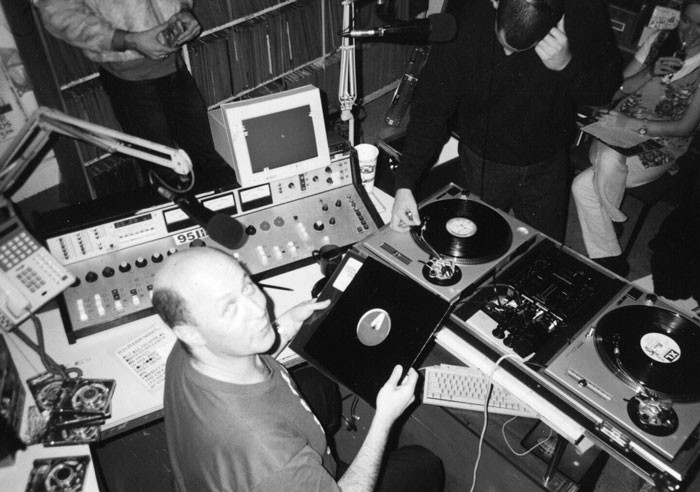

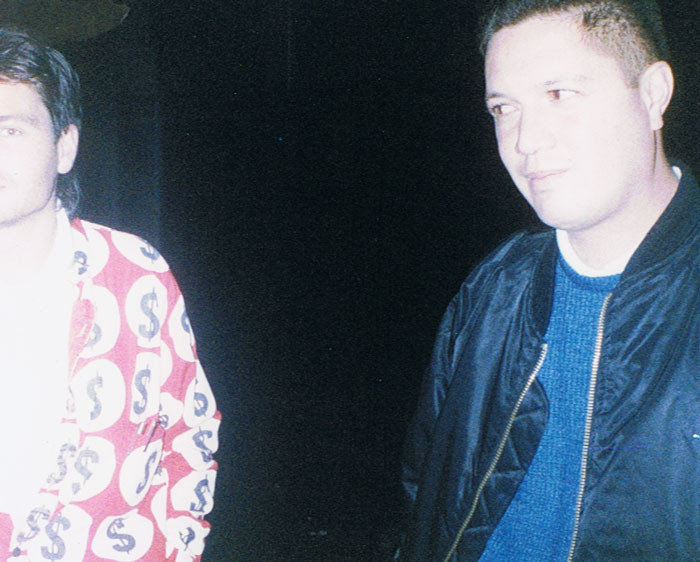

Simon Grigg and Rob Salmon, Beats Per Minute Show, bFM - Simon Grigg collection

The student station’s most popular specialist show is Beats Per Minute, a Thursday night dance music slot hosted by nightclub owner Simon Grigg. Back on back with BPM is the techno show, showcasing sounds from European dance floors, and Planet writer Stinky Jim chips in with his Stinky Grooves two-hour slot crammed with current ragga and reggae sounds.

Cut to High Street, Friday night. Seeing and being seen. That’s the scene outside Box and Cause Celebre. Out to the right of the entrance, a young guy is leaning casually against a bank window, dangling a cigarette from a teenage hand, checking the hang of a new Split top beneath a low-slung glitz bead necklace, glancing down at his new Timberland boots partly exposed under baggy wide-leg jeans, then coolly up again at a group of young women huddled together with a casual familiarity.

Time Sulusi on the door of Cause Celebre and Box - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

Closer to the door, an older fat guy with a mo, curly hair and a plunging open-neck shirt is arguing with the bouncer as a group of his fashion-victim friends mutter encouragement and look nervously around. “Does it make you look tough to talk like that?” the bouncer asks calmly, not looking to budge, reassured by the milling presence of dozens of young rappers, ravers and dance culture debris in that last descending stretch of the street between Freyberg Place and De Bretts.

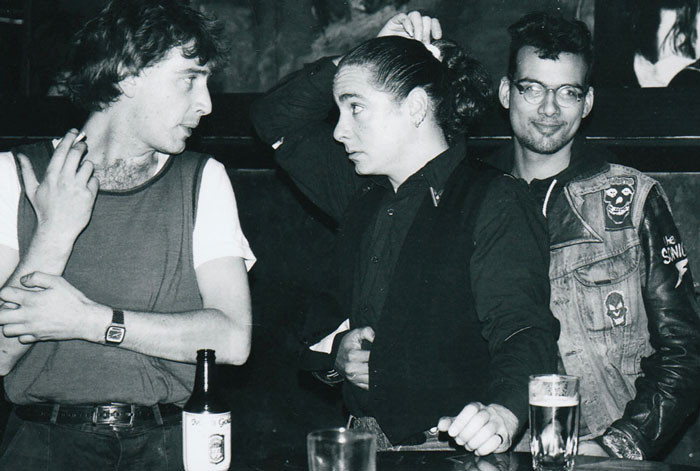

Valery Gherman, Tim Adam (aka DJ Timmy Schumacher) and unidentified friend outside Box - Photo by Samuel Walker

The doorman’s there to ensure only the people who fit get into the club. It’s a modern variant of the old club “mix”, only it’s an “attitude standard” he’s enforcing, not the abhorrent racial mix which some Auckland nightclubs have used to keep Pacific Islanders and Māori out and white paranoia in their clubs at a minimum. Half the club’s dancers know each other says Box and Cause Celebre co-owner Simon Grigg, and he wants to keep an atmosphere with no fighting or harassment of women.

Cause Celebre - Photo by Simon Grigg

A graduate of the Auckland school of punk rock (late 70s/early 80s version), Grigg managed early 1980s chart-toppers The Screaming Meemees and Blam Blam Blam and, through his indie record label Propeller Records, released 50 discs, some of them seminal. He folded Propeller Records in 1983 and, like many young New Zealanders of his generation, suddenly found the Shaky Isles too small and headed for London.

His music tastes were also changing – he’d had a secondary diet of funk via one-time flatmate and Rip It Up editor Murray Cammick, and reggae and Parliament from his punk days – but two factors sealed the new obsession: the raw vital early rap coming out of New York on the Sugarhill and Joy labels, and the emerging club culture in London. With now-legendary clubs like the Wagg Club, Club For Heroes and the Mudd Club among the 30 good clubs pumping out dance music in London, Grigg found himself impressed by the innovative underground dance culture in the city.

“People like to dance, they like to have a good time,” says Grigg. “And there’s so much music coming out, it’s exciting to listen to and you always want something else.”

When Grigg returned to Auckland in 1985, he set up the Stimulant Records label with dance club supremos Mark Phillips and Peter Urlich to release black dance music. Stimulant’s first single, ‘Say I’m Your Number 1’ by Princess, hit No.2 on the New Zealand charts.

Next, Grigg quickly moved into running dance clubs with business partner Tom Sampson: first the Asylum Club in Mt Eden Road’s Galaxy Ballroom, followed by the Playground below Urlich and Phillips' Le Bom restaurant in Nelson Street.

The Asylum - Photo by Ian Marriott

The next move was to High Street and the Siren in the former yuppie hangout Club Mirage, and then, in 1988, Grigg and Sampson bought the club and renamed it Cause Celebre and featured a quiet jazz atmosphere and young acid jazz outfits like Nathan Haines’ Freebass. Celebre’s alter ego, full-on dance club Box, followed in 1990 when Grigg and Sampson bought the old RSA basement next door.

DJ Roger Perry at Siren, 1989 - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

Staying popular among the dance crowd involves more than just playing music in a club. The sounds need to be current, they change at a frenzied pace, what’s in one month can be history the next.

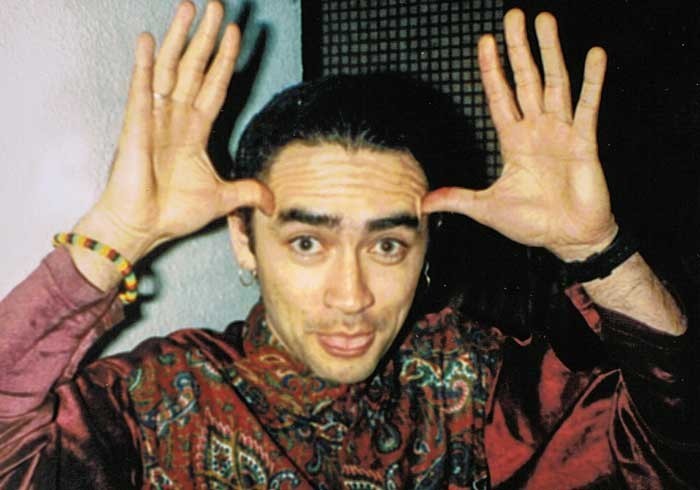

Gerhard Pierard, DJ at Cause Celebre, caught the dance club bug in Palmerston North, where he hosted popular nightspots the Buffalo Bar and Fez Club, playing a mixture of post-punk, rap, hip hop and funk. Stints at Urlich/ Phillips and Grigg/ Sampson clubs followed before he, too, shuffled off to England and Europe where he made a comfortable living playing up to five London clubs a night and select bashes for the London film community for the New Zealand-run Urban Dance Culture, until returning to New Zealand in 1991.

For Pierard, the key to being a good DJ is knowing the audience, being able to read the crowd, and not being afraid to play new songs. Having a new record that goes off rather than just playing the “hits” is where the thrill comes from on his side of the turntable. Nocturnal by both profession and inclination, he’s still looking frazzled at 2pm the next day, but that’s nine hours before the Box and Cause Celebre open. The clubs wind down at 6am, shortly before the morning sun nudges its way into the new day. Then it’s off down the street to the 24-hour cafe for a coffee and toasted sandwich, and home to sleep as the city wakes and shakes itself.

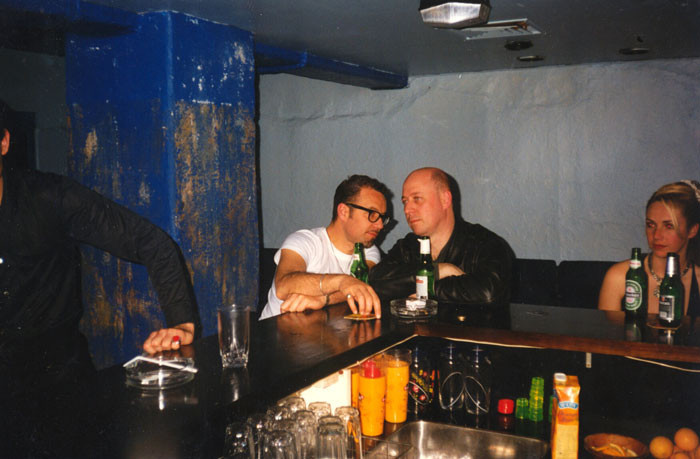

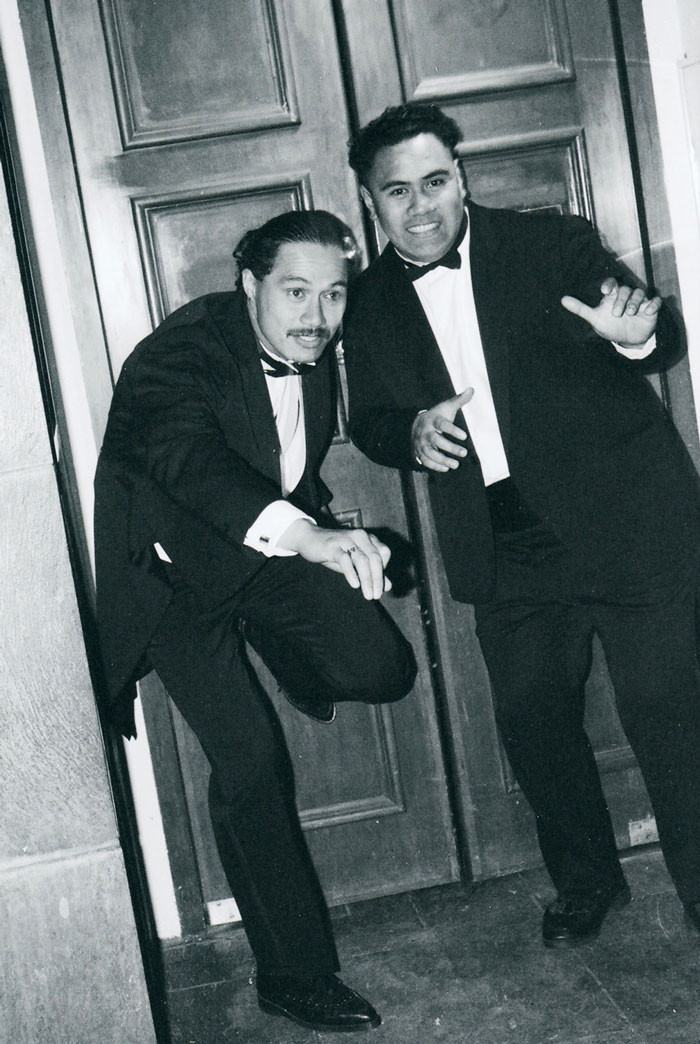

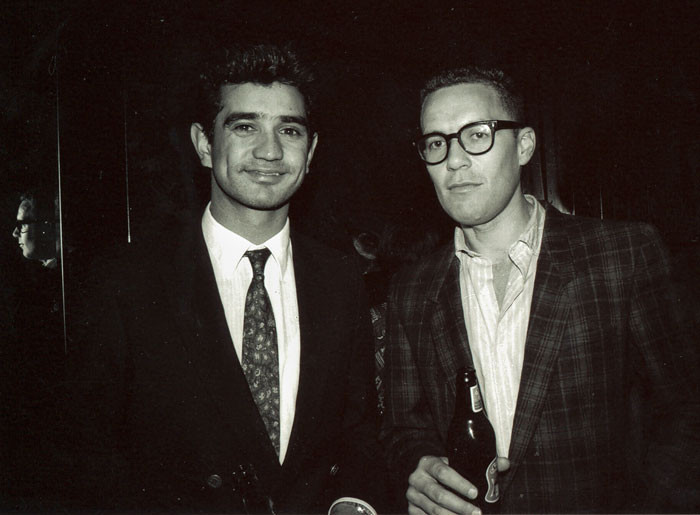

Peter Urlich and Simon Grigg at Cause Celebre. Photo by Mike Stuart.

Most Fridays and Saturdays, 1,000 late-night party people pass through Box and Cause Celebre, fuelled, insists Grigg, by little more than their love of dance and a bottle of beer. Unlike overseas dance cultures, there’s little evidence that Auckland’s relies on psychedelic uppers like ecstasy and acid for its spirit or energy.

The dance club set are mainly older and perhaps more sophisticated than their South Auckland dance culture counterparts. Most have good jobs and work in the inner city, often in retail or the hospitality trade. They’re likely to shop at High Street’s hip clothes shops like Ember, World and Workshop, and hang out at its cafes, making the fashion district an enclave of cosmopolitanism alive both day and night with nattily dressed young people, the smell of coffee and the sound of voices.

The DJ booth at Box - Photo by Karl Pierard

Cut to seen-it-all-before cynic. But it’s all just another fad in the city of fads and fashions, isn’t it? Well, yes and no. Strip away the clothes, the music and the attitude for a minute. What you have left is another generation searching for an identity out of the shadow of early education and family, in those confusing years between school and adult responsibilities. In some ways rap, house or techno could just as easily be beat, punk or disco, but to dismiss it as just another fad is to miss the point.

Music subcultures articulate in dress, music and attitude the tenor of their times, although not that many young people think of it in that way. They’re simply looking for somewhere to belong, to celebrate the naivety and enthusiasm of youth.

Subcultures are often complex and can touch profoundly some people’s lives. They embrace all the things of life. They spawn their own media like Planet and Stamp, their own gathering places like the High Street cafes, shops and dance clubs, and their own values, icons and attitudes. Even when the music is gone and many who lived the life have swung away towards careers and family, the values, attitudes and relationships formed will still colour their lives.

And it’s in what was learned that the lasting value remains. The racial diversity and tolerance of the city’s dance scene in no way reflects Auckland society as a whole, but it’s a positive model of what Auckland should and could be – a Pacific city with a distinct style.

It’ll take some adjusting to, New Zealanders know so little of the people they share a country with, but as Matty J says, it’s time to stop talking and start listening.

The shakers in the local dance scene are young outfits like 3 The Hard Way and people like the frenetic Kane Massey, a Samoan/ German Kiwi who runs a magazine, two record companies and has so many new ideas sliding off the end of his tongue you wonder where he gets the energy.

The media like Planet and Stamp embrace Māori and Pacific Island influences in an unpatronising way by using models of all colours and running stories adult achievers both brown and white, written and photographed by talented young people both brown and white.

And the soundtrack? Well, it’s likely to have changed by the time this story is read, but expect to hear more New Zealand acts on the charts, singing and celebrating the Pacific nation they live in. Noble naive songs like Matty J’s ‘Colourblind’.

“I ain’t no try hard this is the real me

doing what I cart to spread some racial unity.

We may not look the same, not on the outside

but skin should never be an image we hide behind.”

--

This story first appeared in Metro Magazine in February 1994

© Andrew Schmidt, used with permission.

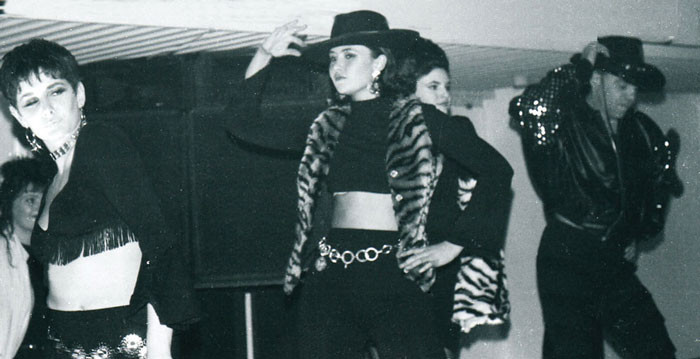

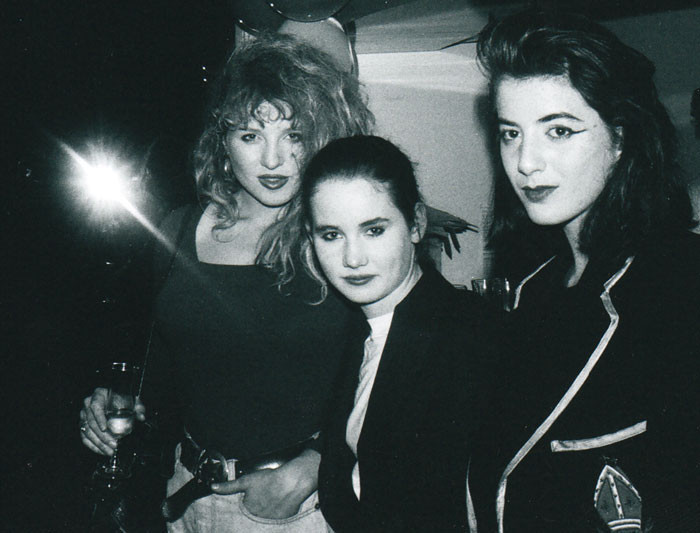

High Street Clubland

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

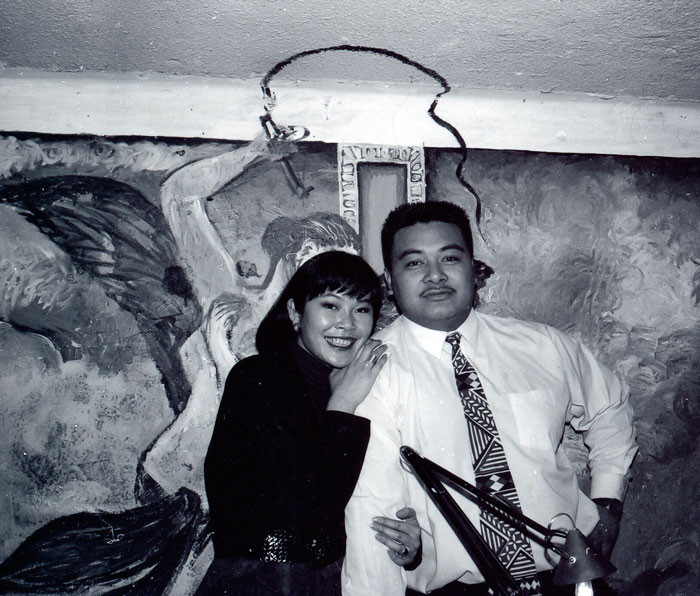

Kerry Buchanan and Sene Atafu - Photo by Simon Grigg

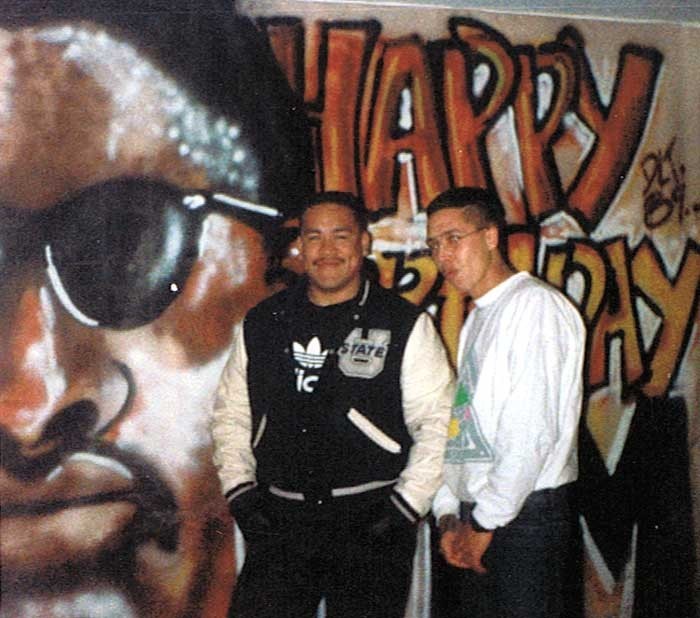

Time Sulusi and DLT with a birthday wall created by DLT for Time, 1989 - Photo by Simon Grigg

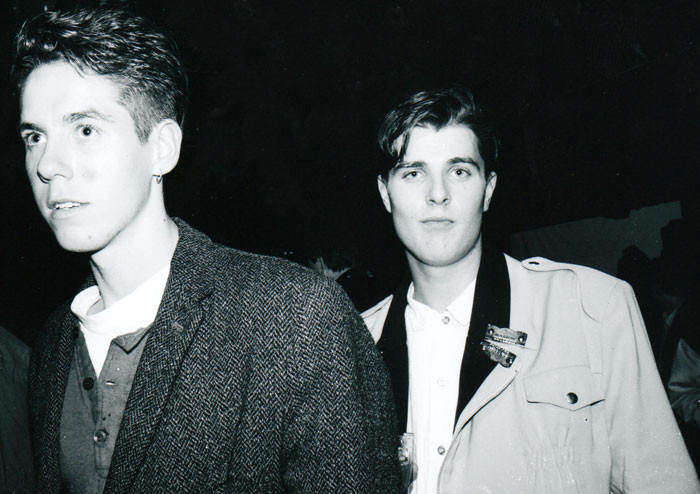

At The Siren, with future Mai FM DJ Mike Haru on left - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

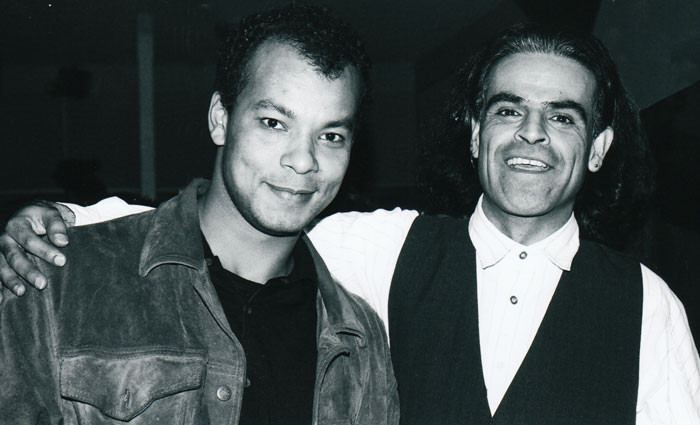

Russell Maiden and Peter Urlich - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Simon Grigg

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

Geeling Ng and Soane Filitonga - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

Greg Johnson, Grant Fell, Barbie and Bevan Sweeney - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Simon Grigg

Mike Weston and Tangata Records co-owner and Upper Hutt Posse manager George Hubbard - Photo by Simon Grigg

Grant Fell - Photo by Simon Grigg

- Photo by Brendan Harris

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

Roger Perry and Eddie Chambers - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

- Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

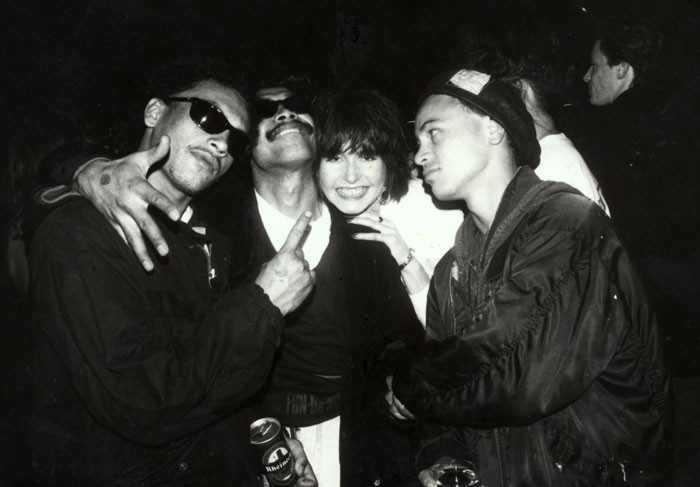

Upper Hutt Posse and friend - Photo by Brigid Grigg-Eyley