The dance music scene in Auckland went through a seismic shift during the 1990s. In the previous decade only a handful of clubs took DJ culture seriously. Now there was a growing tide of new promoters who took dance music to the masses.

The list below is by no means comprehensive, but aims to highlight the main people and events that redefined what was possible. It focuses on inner-city events, many of which took over underutilised spaces that existed within the city fringe. It is true that some brave promoters did try to arrange outdoor raves, though selling tickets could be tricky if the venue was just a corner of Woodhill Forest or the field on the far side of North Head in Devonport.

A hint of dance party culture first arrived through The Asylum club nights at the Galaxy run by Simon Grigg and Tom Sampson in 1986-87. When the venue became the Powerstation, it was booked by DJs Andy Vann and Chris Bateup for their Voodoo Rhyme Syndicate shows, which were primarily hip hop events. Equally influential were the Gothym City parties at Galatos. They were the cusp of a new wave of promoters set on remaking nightlife in Auckland.

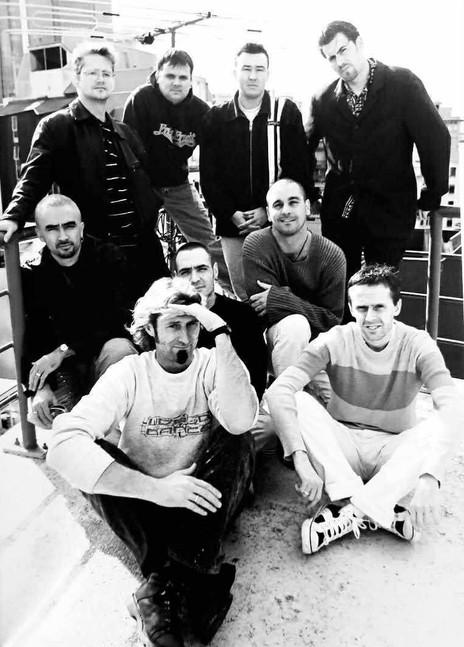

Promoters group shot. Clockwise from top left: Marcus Ringrose (part of the Planet team), Simon Laan, Grant Kearney, Matt Demon, Sam Hill, Phil Clarke, Grant Fell. Centre: Gideon Keith and Graham Young.

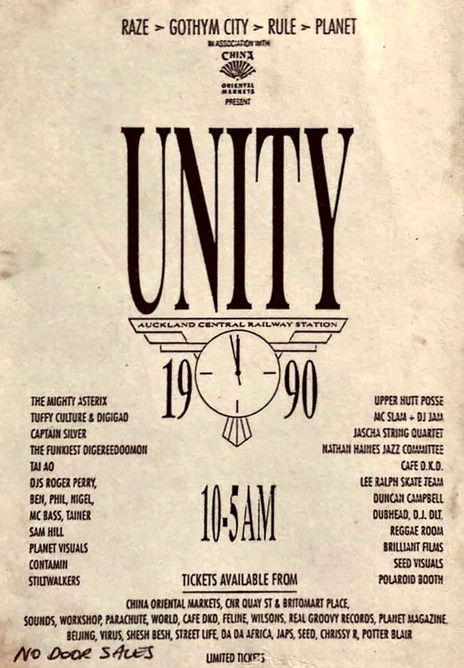

Unity

Unity took place on New Year’s Eve 1989/90 and got the decade off to a flying start. One of the organisers was Roger Perry, who had already gained a reputation for his innovative DJing. He learnt turntablist fundamentals from hip hop, but he wasn’t afraid to mix together surprising tracks – for example, moving from ‘Original Sin’ by INXS straight into ‘Girls Just Wanna Have Fun’ by Cindy Lauper.

Perry met Grant Fell because his girlfriend at the time was friends with Fell’s partner Rachael, and Perry was already a fan of his band, Children’s Hour.

Grant Fell was inspired when his friend Russell Brown returned from the UK with a bag full of acid house records. It led to the pair working together on two Housequake! events at the Powerstation, which each drew 1200 people. It didn’t seem enough to just have DJs, so they also booked hip hop act Upper Hutt Posse and arranged skateboarding demos. They also went all out on the lighting, which included a cross built from old TV sets (made by mutual friend, Justin Jordan). Fell then staged a run of smaller dance parties, including Raise the Roof at Siren nightclub, where Perry was now resident DJ, and Hit The Floor, which was held at the same venue, after it had changed its name to Box.

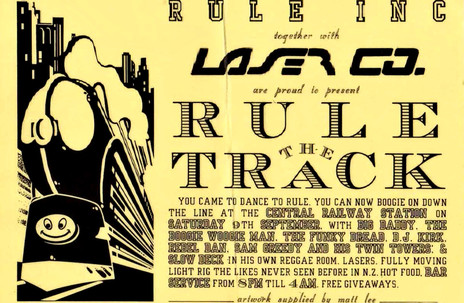

Rule The Track at the Railway Station, 1989. Rule Inc also did two "Destiny" parties at the Auckland Town Hall.

Perry was excited to see a new bunch of promoters entering the scene, but initially felt he needed to be respectful towards the owners of Siren/Box – Simon Grigg and Tom Sampson – so he turned down offers to play outside the club. Then he and Fell saw an opportunity to combine forces to capitalise on the growing momentum.

“There were a few crews putting on parties,” says Perry. “Phillip Campbell and Dave Teehan from Gothym City did parties at Galatos [courtesy of the Galatos Street Theatre crew Matthias Sudholter, Pietch Lesser and Alan Green]. Jason Bringans, aka Jason Miller (who has since passed away), and Costa Zoras put on the Rule The Track event, which was the first dance party at the Railway Station, and they were the first to have a side room that did reggae, courtesy of people like my friend Alex Doyle, aka Slowdeck. Of course, there was already Voodoo Rhyme Syndicate too, which was Andy Vann and Chris Bateup. We reached out to all of them and said, ‘instead of trying to compete, why don’t we all get together and do one big party?’”

The collective booked the Auckland Railway Station for a New Year’s event, which they titled Unity. The station is a heritage building located to the south of Spark Arena and, these days, the building has been turned into the Grand Central Apartments (after a decade of being used as student accommodation). However, at that time it was still an operational train station, though rail services usually lay dormant at night.

Unity poster, 1990. Amongst the promoters named, "Raze" refers to Roger Perry and "Planet" refers to Grant Fell.

They gained a special licence to sell alcohol, arranged for Cafe DKD to set-up a pop-up for the night, and had a “reggae room” hosting acts such as Slowdeck and Dubhead. Their friend Justin Jordan constructed a tall DJ tower and a skateboarding half-pipe with the help of Steve Birrell from Blue Tile Lounge.

“I remember looking down from the tower while I was DJing and watching these guys from Bones Brigade, skateboarding all night. They just happened to be here for some event, so we had Tony Hawk and Steve Cabellero, who just came along for fun and skated like crazy.”

Half pipe at Unity, 1990. - Rohmana Jordan

The Unity party pulled in 2500 punters. However, Miller and Fell’s next hospitality venture, Surge Nightclub, was more fraught and Fell instead focused on his growing workload as a member of Headless Chickens.

Perry went overseas and when he returned home in late 1992 he joined Stylee Crew (later known as 37 Degrees) – a DJ collective that included DLT, Stinky Jim, Dubhead, and Slowdeck. Perry recalls that the events they were involved in could be equally large scale.

“We did a party in an old car park on Kitchener Street – Reggae Owes Us Money. I paid the building manager 200 bucks to get the place on the downlow. Then the last thing we did was an illegal warehouse party at Turners and Growers on Graham Street called Rockers International and 2500 people came … I took a break not long after that. The key to longevity for me was taking a few years out, painting houses and listening to bFM all day.”

The Stylee Crew (later known as 37 Degrees). Clockwise from top left: DLT, Roger Perry, Stinky Jim, Dubhead, Slowdeck. - Photo by Darryl Ward. Dubhead collection

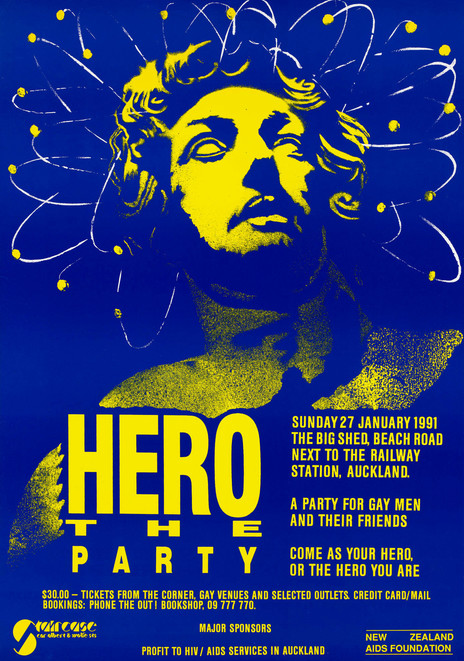

The Hero Party

Homosexuality was finally legalised in New Zealand in 1986. Aside from the moral case for the change, campaigners had also pointed out that this would make it easier to confront the AIDS epidemic, which had arrived on our shores a few years earlier, and led to the creation of the New Zealand AIDS Foundation in 1985.

In 1991, the Foundation wanted to hold an event which would both celebrate gay pride, but also encourage safe sex and condom use. Organiser Rex Halliday later told PrideNZ.com about how he came up with the idea for The Hero Party:

“Research showed very clearly that people who have a strong sense of community have better self-esteem and are better at managing safe sex … My first idea was – why don’t we have a festival at the end of this campaign that says ‘OK, yes, [AIDS] is serious, but we are great, we can actually manage this’? … We are heroic, you know. We grew up in this environment that is completely negative around us. We survived that and learnt to stand up and be who we are.”

Hero Party poster, 1991. - Auckland Libraries ephemera 11134

The event was held in one of the railway sheds which stood next door to where the Unity party had been held. Some in the community had suggested to Halliday that it would be a waste of money, but instead the event raised $5000, which was split between support organisations and the movement to promote safe sex. There were also events with a similar intent put on in other parts of the country, most notably the Devotion Party in Wellington (that same year) and Freedom Party in Christchurch (the following year).

Julian Cook attended many of the early Hero parties and went on to direct the event in 2001 when it took over the Auckland Town Hall and, in 2002, the St James Theatre complex. He says that attending the second Hero Party at Princes Wharf in 1992 was a life-changing event.

“Hero parties were basically a whole new art form for Auckland,” says Cook. “Lavishly decorated venues with massive sound systems and professionally operated lighting rigs. Epic travelling shows directed by Warwick Broadhead, with ornate costumes, props and hundreds of choreographed performers. Formidable drag divas like Bertha the Beast and Pussy Galore descending like Ziegfeld girls from terraced stages. And the iconic New Zealand contemporary dancer Michael Parmenter perilously traversing the shed’s steel rafters, high above the crowds, while laser beams shot at him with words like “queer” and “faggot”.”

In 1994, the Hero Party moved to the Epsom Showgrounds, where it continued to set production standards for dance parties in Auckland under the directorship of Angela Main. The Showgrounds parties peaked in 1997 with a headlining performance from the “Godfather of House”, Frankie Knuckles – his only ever New Zealand DJ set.

“For a generation of queer New Zealanders, their first and most memorable dance party experience happened at the Hero Party,” Cook explains. “To this day, I get approached by lovely people who tell me that the Hero Party at the Town Hall was the best night of their lives.”

Hero Party flyer, 2001.

The Brain and Lagered

Grant Kearney had first been involved in dance parties at the Powerstation in the late 80s as beatmaker for the rap group, Total Effect (one of the groups promoted by Voodoo Rhyme Syndicate). He provided all the samples on his Casio FZ-1 sampler and used it to add samples when DJing, so took the name Sample Gee.

Kearney was also drawn to dance music and he convinced the group’s lead rapper Chris Ma’ia’i (later of 3 The Hard Way) to work on a hip house track he was putting together with hit producer Alan Jansson. They went on to have two hits in 1990 as Chain Gang, ‘Break The Beat’ (No.22) and ‘Jump’ (No.16).

Meanwhile, Kearney had taken over in 1988 as the manager of Sounds Records at 256 Queen Street (aka 256 Records) where two of the other full-time staff were DJs on the rise, Sam Hill and Grant Marshall. Hill had also started out in hip hop and had made a name for his skill at scratching records, which saw him playing on line-ups alongside two foundational names in the genre, Manuel Bundy and Ned Roy.

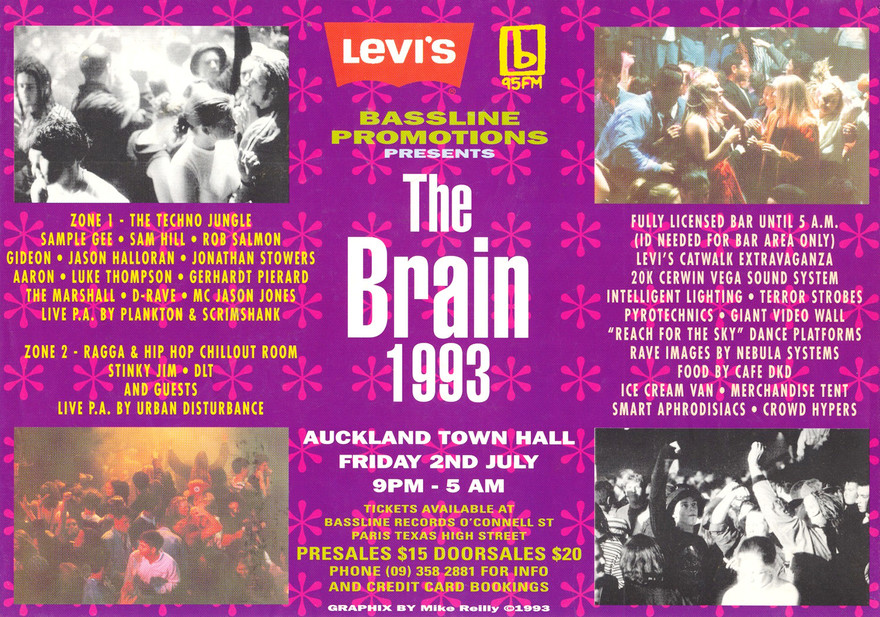

The Sounds store closed after a couple of years, but this left a hole as it was one of the only places where local DJs could source imported records. Kearney and Hill launched their own store on High Street, Bassline Records. They took an increasing interest in dance music and started their own club night, The Brain, at DTM (Don’t Tell Mama, K Rd) in 1991. The name was swiped from an English nightclub and the imagery of a baby head was lifted from an obscure German record they had found.

The Brain drew audiences of up to 1000 to DTM, but eventually the club’s new owners decided they no longer wanted club nights eating into their revenue. The duo took a step up and booked out the Auckland Town Hall in 1993, which had the added benefit of being an all-ages venue (increasing the potential audience). It turned out to be a huge success, though this did cause some problems.

“We asked the venue manager just before the doors opened what it could hold and they told us 1700 people,” recalls Kearney. “I said, ‘we could be in a bit of trouble tonight.’ We’d already sold 2200 tickets. After the event, the management told us they’d never have us back, because people had tried to break in from the rear and damaged the 100-year old back doors. There must’ve been 500 dancers jumping up and down on the podium in the middle of the floor, and they ended up breaking straight through. I’ve never seen anything like it!”

The Brain flyer, 1993.

The Brain continued until the end of the 90s, often taking over the Powerstation for Weekender events which also had an all-ages component (either separate all-ages nights, or making the ground floor all-ages and running the licensed bar area upstairs). The Brain also spun off a compilation CD series, mixed by Australian DJ Vagas (George Vagas).

In the years that followed, Kearney noticed that dance music increasingly began to cross over to the mainstream through acts such as The Prodigy and Chemical Brothers. He jumped on this popularity by creating his own DJ album, Lagered (1996), which was named after the chorus of the Underworld track ‘Born Slippy’ (“Shouting lager lager lager lager”). The first volume sold over 20,000 copies, kicking off not only a successful CD series, but also regular dance parties used to promote them, which toured throughout the country and filled up large venues, among them Auckland’s St James (as did Hill and Kearney’s subsequent Chemistry series).

Stomping Core

In September 1994, Mathew Rudolph (aka Matt Demon) and Brendon Bell (aka Gyro) put on their first event Stomping Hardcore and Trance at Kurtz Lounge on Symonds Street. Demon, Gyro and Mechanism played music to about 150 people and filled the room with lasers, strobe lights, and a smoke machine.

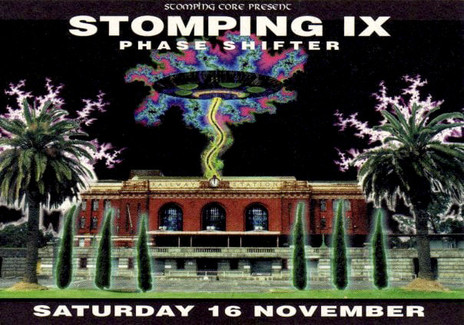

For their fourth gig, Demon and Gyro linked up with Evan Reiman to plan more parties under the promoter name Stomping Core with Demon (Demon Hair Trade) taking care of the show and the music; Bell (Cyber Space Laboratories) operating lighting and sound; and Reiman (Icons Imaging) looking after the print and promotion. Each event saw them increasingly upping the ante when it came to the visual aesthetic, performance art and production scale, as Demon explains:

“We started doing shows on stage using dozens of models all prepared by a team of hairdressers and makeup artists from Demon Hair trade, and doing a choreographed show set to original trance music. Brendon built a 10-watt green laser. We were one of the first to use water-cooled lasers at raves in New Zealand. We could do tunnels and flat scans (a wall of light) and amazing light shows was one of our specialities. The events quickly gained in popularity and size and the group found they required an incredible amount of work.”

Demon and Gyro. - Matt Demon collection

For the most part, the lasers performed incredibly well, though working at the cutting edge did involve risks and at one party the sensor mirrors came loose and the laser burnt a hole in the wall. The distinctive look of their events went beyond lighting and performance art. A lot of effort also went into the print and marketing. At one of their biggest events, Stomping IX, they created custom-printed luminescent plastic tags for all the crew, which gave off a fluorescent glow under the black lights.

The Stomping parties changed venues over time and grew to the point where they were hiring large spaces such as the Oriental Markets downtown (Stomping VII: Kundalini Rising) and the Railway Station (Stomping IX: Phase Shifter).

Stomping IX: Phase Shifter (1996).

The key musical style was Acid Trance, but genres blended freely at this stage and they always had a side room devoted to drum’n’bass which was organised by Jay Monds (aka DJ Pots/Jay Bulletproof), who became a regular along with Riddle and 48-Sonic, as Demon recalls: “As much as we enjoyed creating the shows, they were unfortunately not very profitable or financially sustainable – and honestly were more just a labour of love, so after the 12th gig we decided to call it a day.”

Lightspeed Productions

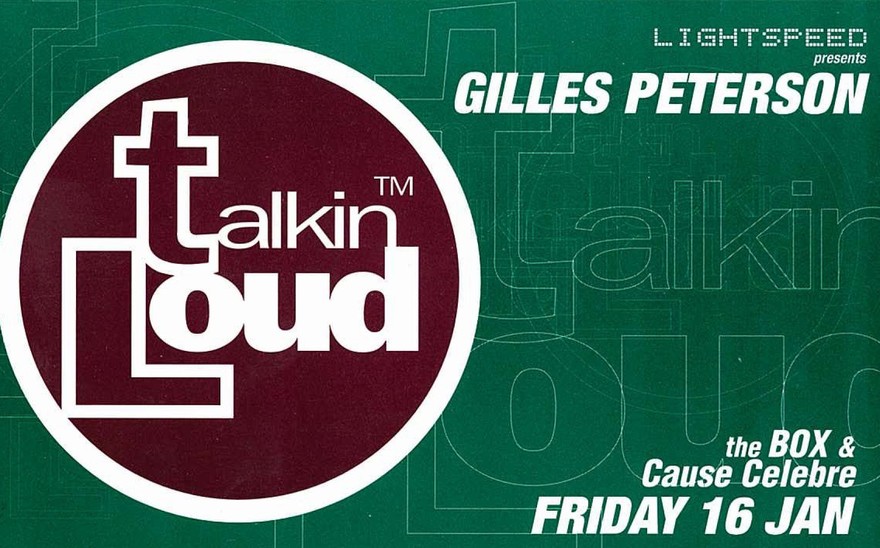

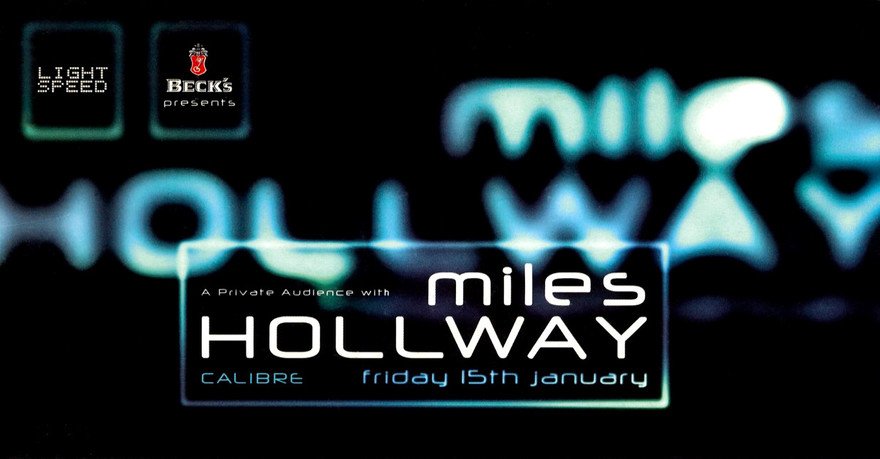

Chris O’Donoghue first started putting on shows at Box, Cause Celebre and Herzog, then decided to partner with Tom Sampson from Box to do bigger shows. The name for their company struck O’Donoghue out of the blue: “I had a Lightspeed dial-up modem sitting on my home office desk …”

O’Donoghue had noticed how a generation of New Zealanders in their late twenties and early thirties was returning home from overseas after experiencing the club scene in the UK. There was a growing appetite for big House music events, but the production standards would have to meet their expectations.

“Australian touring agents were offering international house and techno artists for New Zealand bookings. In Australia, Saturday is typically the most viable night to host an event. This opened up possibilities for Auckland gigs on Friday nights.”

Gilles Peterson's Talking Loud with Mark de-Clive Lowe, Roger Perry, and Tim Adams, at Celebre/Box, January 16 1998, one of 29 Lightspeed shows in 26 months. - Simon Grigg collection

For a brief time, Lightspeed Productions also included Greg Herron. Then O’Donoghue and Sampson brought in Julian Cook, a former contemporary programming coordinator at the Aotea Centre, as their in-house publicist and copywriter, though O’Donoghue believes that his “skills and responsibilities spanned most of the operation.” This was prior to Cook’s work as director of the Hero Party, and his relationship with the event actually saw Lightspeed underwrite the Hero Party at the St James.

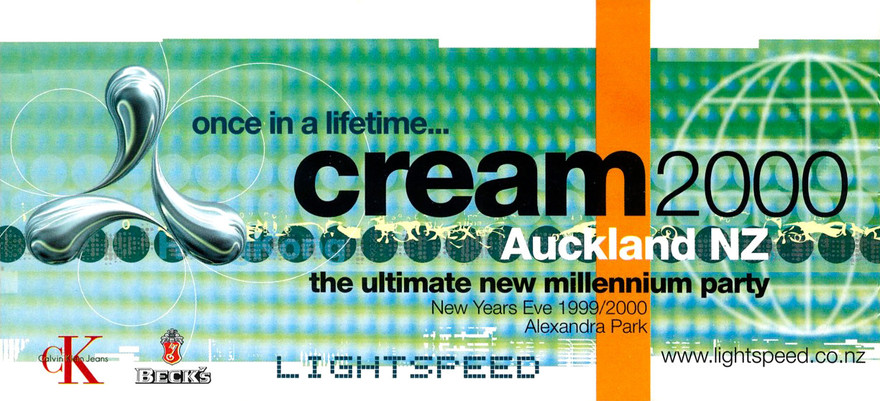

Lightspeed licensed well-known overseas brands (Ministry of Sound, Cream) and brought over some of the biggest names in the business, including Roger Sanchez, Danny Tenaglia, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, Stacey Pullen, Carl Craig, Ian Pooley, Derrick Carter, Coldcut, Gilles Petersen, Kenny “Dope” Gonzalez and Mark Farina.

Miles Hollway: an early Lightspeed event, 1999. - Julian Cook collection

Through Dick Johnson, O’Donoghue had met Pete Jenkinson from Manchester based label Paper Recordings, and drew on their connection to bring over many associated acts, including Miles Hollway, Elliot Eastwick, Ben Davis, Erik Rug and Ivan Smagghe (Black Strobe).

Lightspeed were the first to identify Ellerslie Racecourse as a venue for large dance parties, which could draw in over 5000 attendees.

“It was disused for much of the year, and the management was receptive to our approach,” says O’Donoghue. “It had the scale and facilities, enabling us to put in a big sound system and lighting rig. This gave our patrons the big club feel they were looking for. The other key factor was that it seemed far enough from residential properties to control the noise. We got away with it, with very few sound complaints from neighbours. The first events there were a huge success, and the enthusiasm and positive feedback from the patrons was emphatic.”

O’Donoghue is quick to give credit to others in the community who supported Lightspeed in its heyday.

“None of this could have happened without the support and efforts of all the local DJs, including Bevan Keys, Dick Johnson, Soane, Greg Churchill, Roger Perry, Dan Clark and Nick Dwyer. Lightspeed also had a close relationship with 95bFM. We had lots of great friends working at the station and identified with their sense of humour and unorthodox approach. Aaron Carson, Steve Simpson, Josh Hetherington, Mikey Havoc, Steve Newall and Jules Barnett helped us immeasurably. bFM presented the majority of our shows, always backed by the seminal specialist shows like Thursday night’s Beats Per Minute show with Simon Grigg and Saturday morning’s Nice and Urlich.”

Cream flyer, New Year's Eve, 1999/2000.

However, O’Donoghue began to find that the scene was losing some of its heart. “The golden period for these club nights and large events was the late nineties,” he says. “By the turn of the century, things were changing. There was now much competition and stepping out in Auckland had become saturated with options. Despite the most well-intentioned efforts, many of the things that were good about Auckland nightlife were quickly eroded.”

Sampson left Lightspeed to manage the St James, but the upside was that it gave O’Donoghue the opportunity to use The Grand Circle for Lightspeed club nights. This allowed him to move away from super-club events, while still putting on regular shows featuring both international and local headliners, with Soane and Bevan Keys as resident DJs.

Soane at The Grand Circle, St James, Auckland, 1999. - Photo by Karl Pierard

Soane worked closely with O’Donoghue on many projects, including two mix CDs for Lightspeed. His Tongan Chic radio show on bFM was co-hosted by Nick Becker, who had joined Lightspeed for a time as sponsorship ambassador. Released on Paper Recordings, Soane had a run of UK club chart hits, and Lightspeed helped to arrange a tour through the UK and Europe.

Eventually, O’Donoghue moved back to his original career as an arborist and the Lightspeed name was retired, though it is still synonymous with this era of nightlife in many people’s minds.

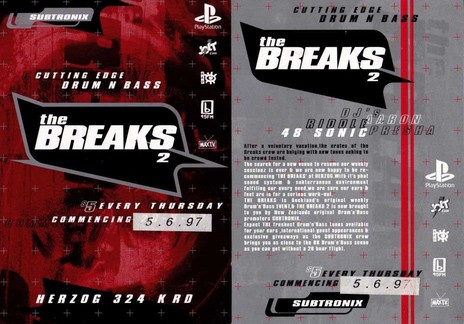

Subtronix and The Breaks

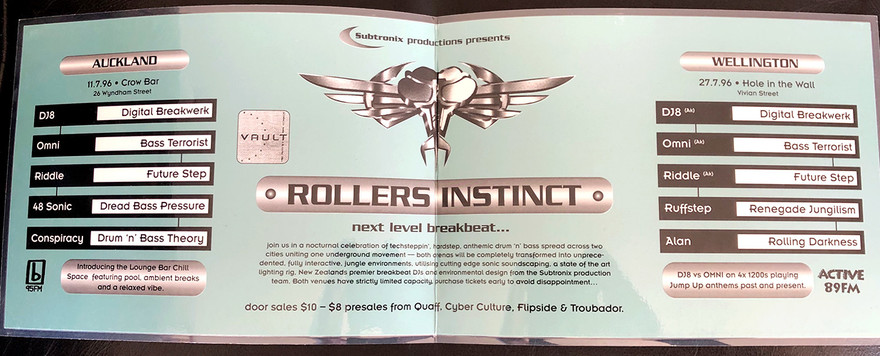

Subtronix was started in 1996 by DJs Andy Pickering (aka DJ8) and Dena Benfell (Omni). Their first event Rollers Instinct was a double-header, at Crow Bar in Auckland and Hole In The Wall (now Valhalla) in Wellington.

Rollers Instinct, Subtronix (1996). - Andy Pickering collection

The pair were soon joined by Dave Roper, who’d met them at local clubs like Box. Roper had experienced the UK club scene first-hand when visiting in 1988 and 1994 and had already worked on promoting shows – including an early dance party Real-to-Real put on by Andy Vann at the Powerstation.

Subtronix kicked into a higher gear by booking UK legend Grooverider to perform at Box and from then on, sought ways to connect with the international scene, bringing over acts and importing records.

In 1997, Pickering left Subtronix and moved back to his hometown of Wellington to finish his degree. When he returned to Auckland he founded Remix Magazine with Tim Phin. Its early issues provided in-depth coverage of local dance music and each issue included a mix CD. Benfell moved to Australia, which left Roper in sole charge.

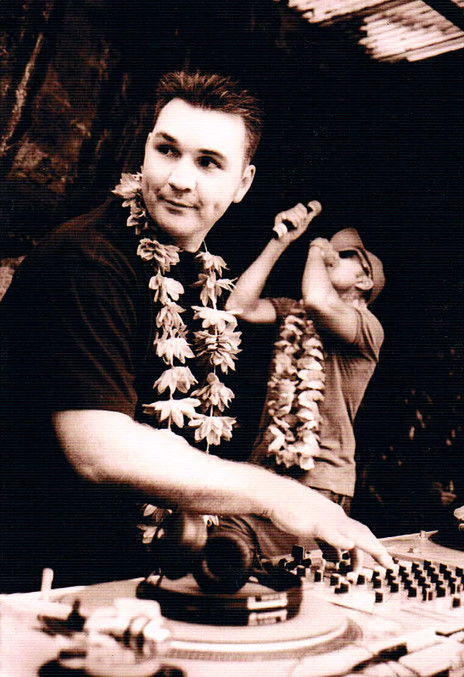

Dave Roper in the late 1990s. - Simon Grigg collection

Meanwhile, Roger Perry had been asked to help manage a new nightclub, Calibre, which had taken over an underground Japanese restaurant in St Kevin’s Arcade in 1996. He often DJ’d from the bar so he could also serve drinks. It was only after being removed from the job, then asked back, that he was able to get the club pumping. Early on in the process, Perry asked DJ Presha (Geoff Wright) if he’d like to move up from Christchurch to DJ at the club and this led to the creation of a regular drum’n’bass night, The Breaks.

Roper and Wright decided to combine forces and gradually increased their connection with the worldwide scene, as Roper recalls.

“For me to book an artist, it normally started with me actually looking on the vinyl and then seeing there was a phone number. I’d ring the label and they’d put me in touch with someone else, who’d put me in touch with someone else. When we would bring DJs over here, they would listen to the support sets and they were bloody surprised by how good our DJs were. That gave you a chance of giving them their tape and having them actually listen to it … DJs were very fond of New Zealand.

DJ Presha with Kemistry and Storm.

“Artists like Kemistry and Storm would tell me, ‘Outside of the UK, this is my favourite place to play.’ Doc Scott played the whole night once – not booked for it, not paid extra. He did it because he loved our events. They wouldn’t just come over for a few nights, they’d often stay for a couple of weeks. So we’d have Ed Rush and Optical hanging out with us at a BBQ or kicking back playing FIFA on Playstation.”

Over these years, Roper also worked on rock concerts by international touring acts including Suicidal Tendencies, Anthrax, and Morbid Angel. It meant he was certainly capable of putting on a show at somewhere like the Auckland Town Hall, but he decided not to push the capacity of his Subtronix shows, as they moved from Herzog on K’ Rd to Fu Bar (lower Queen Street). It was this vibe that drew visits to his club night by the likes of Kiefer Sutherland and Janet Jackson, who hung out and enjoyed themselves without the need for velvet ropes or a VIP area.

Roper worked hard to create a close-knit club experience. “The club experience is very different from a concert” he says. “The dance music genres each had their own subculture and they were built for clubs, where an event could run through until 6am. They weren’t built for big venues, they suited dark, claustrophobic spaces where the music overwhelmed you. It also meant we kept the barbarians at the gate. It provided a filter that kept out people who didn’t fit into what was happening. New Zealand culture was very different back then. There was a strict kind of social conformity, where if you looked a bit different or liked different music or weren’t into sport, then you were called a freak or a faggot. Clubs were where people found their own place – their family, their friends. I was very conscious that I didn’t want people from outside ruining that and destroying what we had.”

The importance of Subtronix is not just that they introduced so many young New Zealanders to drum’n’bass. They also made it possible to get the hottest records through their importation company Subtronix Distribution, and then went into releasing local acts overseas with their label, Subtronix Recordings. This helped Bulletproof and The Upbeats to get their first foothold in the UK.

Roper parted ways with Presha in 2004, but continued to do Subtronix events up until 2014 and remains in the music scene to this day (with a notable stint co-running the Northern Bass festival). One of Roper’s fondest memories from his Subtronix days is bringing Goldie over at the height of his fame.

“This was peak Goldie: fresh off the James Bond film, in the headlines, partner was Björk, Metalheadz in full swing,” says Roper. “We couldn’t afford his fee outright, so I onsold him to the Big Day Out. They took him for the full Australia-New Zealand festival run. I was advising BDO on Boiler Room programming at the time, so it all lined up ... BDO was a big deal – massive media tent, TV crews everywhere. So Goldie walks into a live interview and the host says something like, ‘You must be looking forward to hitting the Big Day Out stage soon?’ And Goldie, deadpan, goes: “Well actually, I’m here looking forward to playing Dave’s gig. That’s what I’m looking forward to.” The whole tent froze. He was supposed to be there for them, but he made it clear where his heart was. Classic.”

Nice’n’Urlich

Peter Urlich started his music career as lead singer of Th’ Dudes, but went on to run some of the most influential bars and clubs of the 1980s (A Certain Bar, Berlin, Roma) and he even started one of his own with business partner Mark Phillips (Brat/Playground). They then began putting on unlicensed dance parties in warehouses around the city. Roger Perry recalls that he and Simon Grigg were asked to DJ at an infamous event on Nelson Street.

Peter Urlich and Bevan Keys at a Nice'n'Urlich party in the early 2000s. - Simon Grigg collection

“I was DJing and looked up to find six cops right in front of me in a line,” says Perry. “One of them just said, ‘turn it off, mate’. They confiscated all the alcohol and probably drank it themselves. The supplier was Joseph Goddard, who owned a restaurant called Veranda Bar and Grill, and he took the police to court and won, so got all his alcohol back.”

It was front page news when Urlich and Phillips also appeared in court weeks later but were let off with a warning.

During the mid-90s, Urlich began a DJing duo with Clarkee (aka Phil Clarke), before settling into a long-term partnership with experienced DJ Bevan Keys. Clarkee remained a regular at their shows. As Nice’n’Urlich, Urlich and Keys played a style of funky house music that could work in a number of different modes. It nicely suited their role as hosts on the Saturday morning slot on bFM, providing good vibes to get listeners started on their weekend.

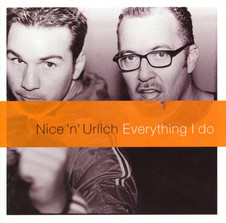

Nice’n’Urlich in 1999. - Brigid Grigg Eyley

They were soon headlining their own shows and producing top-selling compilations through Grigg’s label huh!. Everything I do (1999) sold 40,000 copies, Nice’n’Urlich 2 (2001) sold 30,000, and even by the third release I’ll Never Forget Whatshisname (2001) they were still moving over 20,000 copies. By this stage, they were big enough to headline their own events at the St James, drawing in over 2000 attendees.

Nice'n'Urlich - Everything I do (1999) released on Huh! Records.

Oonst and the Titanic

Mikey Havoc (ex-Push Push, aka Mike Roberts) was drawn into putting on dance parties through co-owning the bar Squid on O’Connell Street. He worked with promoter Nick D’Angelo (aka Simon Laan) to put on special nights such as Island of E and Cheap Sex. He also learnt to DJ himself through the kindness of his friends in the scene – Gideon Keith and Chelsea – who let him learn the basics by using their turntables.

Gideon and Chelsea.

He inadvertently gave a pair of local promoters the idea to do a series of rave parties on a boat. “One of my best friends was going to England,” says Havoc, “so I spent this ridiculous amount of money to hire a really expensive boat so we could have a party for him. We loaded this soundsystem onto this super-yacht style boat and we were friends with all these people who were playing out in clubs, like Gideon, Chelsea, Luke Da Spook and Grant Fell. So the music was pumping and we were all dancing. It ended up being one of the best afternoons ever. Matt Nicholls was there and he joined up with Phil Randall then they took the idea and ran with it. They were the guys who went on to run the Wyndham Bowling Club.”

The first iteration of the event was held in 1997 on a fairly upmarket boat called the American Eagle and the attendees were largely from their extended friend group, but they subsequently hired retired ferries such as the Kestrel so they could have a bigger crowd aboard. Havoc found that it worked surprisingly well.

“The first one we had a few issues with record players being unstable and a bit of sea spray getting on the records, but it was so much fun. The great thing about a boat party is that as soon as you start pulling away from the dock, all the worries and the bothers of your everyday life just drift away behind you. We even did a daytime event where we parked up by the Chelsea sugar works. You’d jump off the boat for a swim and then come back up the ladder straight into the middle of the dancefloor!”

Titanic flyer, circa 1999.

The Titanic parties went on to book some of the top names from the scene, including Soane, Phully and Phillipa, and were influential enough that they were followed by a run of similar events, including The Loveboat, Voyeur Voyage (which doubled as a launch for the BlueJeans energy drink), and Splash (featuring Sam Hill, Sample Gee, and The Marshall).

Havoc was also the breakfast DJ on bFM, where he gradually slipped more dance tunes into his playlist. The station had always been known for its specialty shows, but now it heralded the latest tunes throughout the day too. It therefore provided an important mouthpiece for the scene, especially since George FM was still in its infancy (George began as a bedroom station in 1998, and only became a commercial station in 2003).

However, it was still a contentious move when Havoc and another DJ, Jason Rockpig (aka Jason Hill), planned to put on a dance party at the Mandalay in Newmarket in 1999.

“The promoters around town were pretty sceptical of us and even the other people at bFM. We had a staff meeting on the day of the first one and I remember asking ‘what should we do if it sells out? Should we do a few more door sales or what?’ Some of the other people in the room thought I was crazy, they didn’t believe it would ever be that popular. Then it sold out by that afternoon.”

The event was named Oonst, which was an onomatopoeic word used by Gideon to describe the sound of a dance music beat thumping away. The key to its success was its ability to draw in listeners who might have traditionally listened to “alternative” music and it grew massively over the following four years, joining the increasingly regular dance parties that now filled up the St James.

Roger Perry has fond memories of performing at Oonst in its heyday. “The promo copies of ‘It Began In Afrika’ by The Chemical Brothers and ‘Where’s Your Head At?’ by Basement Jaxx had just arrived in the country. So I made an agreement with Havoc – you can do the Chemical Brothers track and I’ll do Basement Jaxx. The St James was packed and I’d just stopped doing drugs and drinking alcohol. I was putting myself on a full-on cleanse so I was slightly anxious, but when I dropped that Basement Jaxx tune, I looked up and the whole main room of the St James was jumping up and down. It was just incredible.”

DC Productions and One Green Apple

Jon Davis grew up in Britain, where he had success in both the DMCs and the UK DJ of the year competitions. After globetrotting for a couple of years playing in Australia, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia he arrived in New Zealand, landing a job at the newly opened Siren, which became Box.

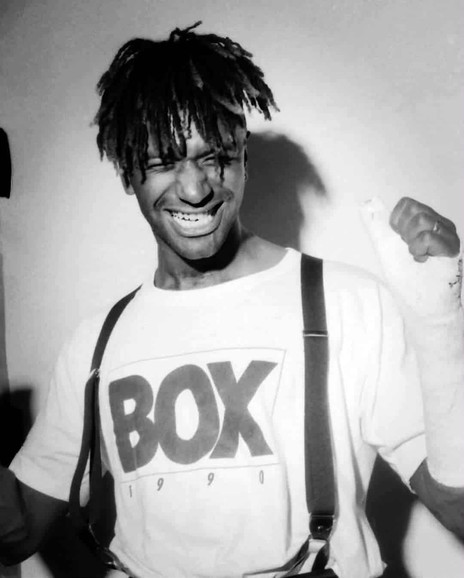

Jon Davis when he was DJing at Box.

From the early 1990s onwards, he began putting on regular events. Initially he worked with Ketzal Sterling and Rob Warner under the name DC Productions and they created a run of memorable events, including the Cold Power foam rave, New Zealand’s first “snow rave”, a massive rave at Rainbow’s End, and an Ibiza dance party held on Waiheke.

He then began working with another partner to create One Green Apple, which kicked off with an all-New Zealand line-up at the Powerstation. Davis had DJ’d a lot in the local scene himself and brought this knowledge into deciding which DJs would work for which shows – whether as headliners or taking the different role of supporting a visiting act from overseas.

“Jolyon Petch always understood the warm-up assignment. If I needed a DJ to carry a local talent room, then Leighton, Siren, Andy Day, and Nick Collings were my regulars, or Rob Warner and Emma Green for the House side of things. When we had the odd jungle or techno headliner then Matt Drake and 48-Sonic. I also regularly called on Mike Cowie and CJ Davis.”

Jolyon Petch at a One Green Apple event. - Mike Cowie

DJ Siren playing at one of Jon Davis's events in the early 2000s. - Mike Cowie

One Green Apple was soon putting on some of the biggest dance events in Auckland and Davis’s workload soon meant he was able to switch to being a full-time promoter.

“Slinky was dropped in our laps by Dave Hook who’d been approached by Future Entertainment in Australia for a satellite gig to the Australian tour, but Dave didn’t feel he had the chops to make it happen. Godskitchen and a few others followed on. I was working for Mai FM at the time of Slinky, I had to make a choice to do one or the other. I ended up going for the ‘fun’ option. Yeah right!

“Promotions is gambling. You put your stake down knowing the odds at point A in time, but the weather, competing events, and world events can all conspire against you and you end up only covering costs (effectively losing money because you’ve worked three or four months for nothing) or even losing money, which in these high-cost endeavours can be devastating.”

In 2001, Slinky had one of its biggest events with over 6,000 people filling up Alexandra Park. This size of event became less viable in the years that followed, given the increased competition in the marketplace, though Davis continued to be one of the top promoters in the scene for many years afterwards.

Deep Hard N Funky and Our:House

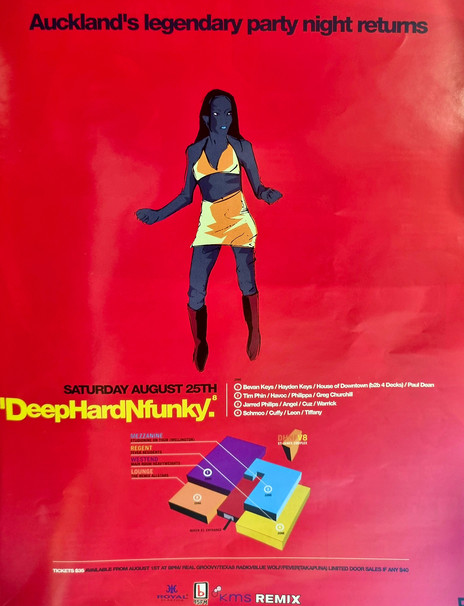

Deep Hard N Funky was started at the tail end of the 90s by Ricky Newby and Salina-Peal as a club night at Cirque on K Rd. They were soon working with some of the most well-known DJs on the scene, including Roger Perry, Mikey Havoc, and Philippa. Tim Phin also DJ’d at the event and he joined the team when they decided to take it to the next level.

“I jumped into it to help with programming when it was moving to the St James,” says Phin, “when it jumped up a level into the big 3000-plus people size. Then it later went to Vector arena, with around 5000 people.”

Deep Hard N Funky, Auckland Dance Parties 1990-2000 - Mike Cowie

In 2023, Deep Hard N Funky celebrated its 25-year anniversary with an event at the Ellerslie Racecourse. Over two decades, it has also taken over other large venues including the Auckland Town Hall and the Trusts Arena, as well as bringing over some of the biggest names in the business, including Roger Sanchez, Groove Armada, Princess Superstar, Swedish House Mafia and Mylo.

Deep Hard N Funky ad for St James event.

Phin had an even deeper involvement with one of New Zealand’s longest consistently-running dance parties, Our:House.

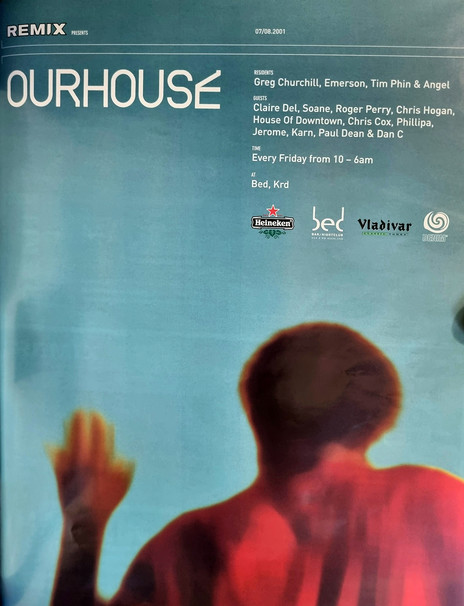

“Our:House kicked off around about the year 2000. I had done some CDs on Remix magazine, then after traveling to the UK and US I got some ideas for some great club nights. I saw in New Zealand/Auckland that there wasn’t a home anymore for resident DJs. We kicked off at Bed Nightclub with Greg Churchill, Angela Fisken, myself, and Emerson Todd as resident DJs. It was weekly, every Saturday. It went from Bed Nightclub onto Coast Nightclub, which is actually a legendary downtown space on a rooftop. It had five rooms, held 1,000 people, and it had a luxury feel that everyone kind of dressed up for.”

Early 'Our House' ad, 2001.

While some DJs in the scene were drawn to more minimal house, the name of the event encouraged the DJs to drop big tunes that got the crowd moving. This approach was incredibly popular and Phin saw the event grow far beyond his expectations.

Remix All Stars ad in Remix magazine, 2001.

“We went from club nights on K’ Road, to 1000-person nights that were monthly, and then onto the big St James, big events with 2000+ people, and then onto big festivals of the 5000 to 10,000 size. The highlight for me would be playing after Calvin Harris, Skrillex and Diplo to 12,000 people.”

The key to the success of Our:House was its ability to smoothly move from the tail end of early-00s house music into the new EDM movements that followed, which also saw them bringing David Guetta. The steady increase in size brought with it plenty of stress, but Phin always went back to the love of DJ’ing that got him started in the first place.

“It could be both exhilarating and highly stressful,” he says. “You’re running on dopamine and cortisol at the same time, but as a DJ for me, there’s nothing better than playing in front of that crowd.”

Postscript

The dance party scene continued to grow enormously in the early 2000s. Case in point: the Gatecrasher event at Aotea Centre in September 2000, which drew 4500 attendees despite being on a Thursday night with an $80 ticket price. However, the era of 4000-5000 capacity mega-raves gradually came to an end as the decade wore on, though the 1000-2000 person dance party remains. Even the University of Auckland’s yearly Orientation was based around a massive dance party at the St James.

By that time, Big Day Out had turned over the Mt Smart Supertop to DJs, creating the heaving sweat-pit of boogieing that was the “Boiler Room”. New North Island festivals also tapped into the love of dance music, most notably Splore (1998 onwards), Northern Bass (from 2011 onwards), and Rhythm and Vines (2009 onwards).

There was an effect beyond the nightlife scene too, with the arrival of many successful music producers who had come up within this vibrant musical culture. Two obvious examples from the names mentioned above are Greg Churchill who placed a song in the UK charts, and Jolyon Petch who has had multiple streaming hits.

When the 90s began, dance music hadn’t been taken seriously. By the 00s, there was no ignoring it. Many of the events and promoters mentioned above were instrumental in causing this change of mindset, and DJ culture in Auckland remains strong to this day.