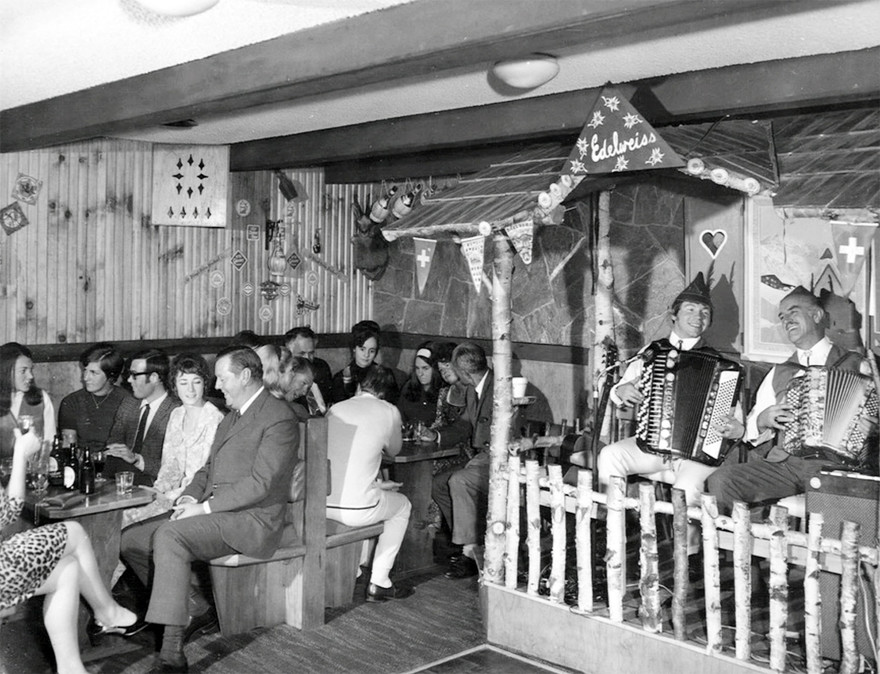

John's Place, Rialto Arcade, Newmarket, 1971 - Rykenberg Photography, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19710522-09

Today the most common place to see and hear live music is at a pub that doubles as a venue, followed by festival and arena shows. Alcohol is usually available at all. Things haven’t always been this way: the twists and turns of Aotearoa’s liquor laws resulted in almost a century during which public music performance and drinking were largely kept apart.

Early alcohol laws

Alcohol first arrived here with early European settlers. Māori were initially unimpressed, naming it “waipiro” – stinking water. The Europeans sang while they drank and their songs were often about drinking itself, as in this song adapted from a 1864 poem by Australian writer, E J Ovenbury:

Landlord shouting is uncommon

He’s kidding you to dance and play

How the devil can a man keep sober

In those shanties by the way?

The “shanties” in the lyrics were grog shops that were popular during the gold rush of the time.

The first serious attempt to govern alcohol sales in New Zealand came in 1842, when alcohol licences were introduced and trading hours were limited. It was followed by an 1847 law that forbade selling alcohol to Māori, though this just meant the trade continued illegally and with no quality controls (restrictions lasted until 1948). Exact laws varied by province. For example, Otago required a special permit before music and dancing were to be allowed to take place within a bar.

Otago Daily Times, 20 October 1866.

In 1874 came the first attempt to remove entertainment from drinking establishments, when Parliament decided they needed to stop the practice of “hiring women and young girls to dance in rooms and places where liquors are sold”.

The local temperance movement then argued that any form of entertainment at a pub was a manipulative inducement towards drinking. The response came in the form of the nationwide Licensing Act of 1881: pubs were banned from having concerts, theatrical performances, or providing billiard tables. This saved publicans some expense, but many of them were subsequently put out of business because the Act introduced three-yearly referendums allowing residents to turn their district into a “dry” area with no alcohol sales allowed.

Another change from this period – that would eventually have an impact on the music industry – was a requirement for places that sold alcohol to provide at least six rooms of accommodation and offer meals. The aim was to ensure adequate lodging along the country’s growing transport routes, especially since “public houses” (hotels) were already the prime location for drinking. The era of the “pub” had begun.

The temperance movement pushed onward and had its own songs as a battle cry, including this one sung to the melody of ‘When Johnny Comes Marching Home’:

The Temp’rance cause will win the day:

Hurrah! Hurrah!

The curse of drink be swept away:

Hurrah! Hurrah!

Then will our land in truth be free,

No longer slaves to drink we’ll be

A happy Temp’rance Nation we

When victory is ours!

Brassed off about booze: the Ladies Temperance Brass Band, photographed by William A. Price in the 1910s, presumably in the Auckland area. - Alexander Turnbull Library 1/2-000336-G

The temperance movement came close to achieving its goal. In 1910 the drinking age was lifted from 18 to 21. Then in 1917, a temporary wartime measure was introduced forcing pubs to close by 6pm. Men now only had time for the briefest of after-work drinks before heading home to their families. The patronage in pubs was almost entirely men; even female bar staff were banned from the 1910s, unless they were the business owners or the owner’s family.

Hotel restaurants could stay open until 8pm, but publicans soon realised that the greatest profit was generated by the “six o’clock swill” between work’s end at 5pm and the pub closing at 6pm. If music had been allowed it would have slowed the pace of drinking, and publicans were happier without it.

In 1919, there was a referendum which came close to outlawing the sale of alcohol across the country. It looked set to pass, until the votes of overseas-stationed New Zealand soldiers overturned the measure.

Every three years, the country voted on whether the alcohol rules should change or remain the same, or whether alcohol might be made illegal entirely, but the “temporary measure” of 6pm closing would endure for 50 years and the banning of music from licensed establishments would last almost as long.

Bending the rules in the jazz age

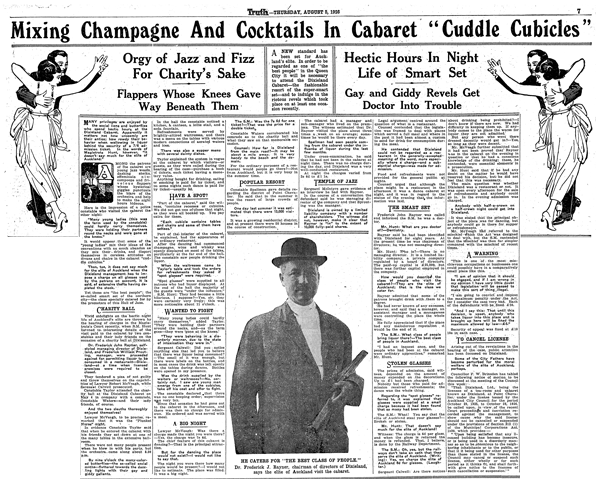

With music performances excluded from pubs, people had to find other places to listen to bands and dance. Public halls throughout the country became dancehalls, including those owned by Masonic sects (such as Auckland’s Masonic Hall on Upper Queen Street and nearby Druid’s Hall, now Galatos). Often cinemas would become dancehalls once the films had ended for the night. Purpose-built dancehalls began to emerge in the 1920s as the jazz age got underway. But how could you have a glitzy night of dancing without champagne and cocktails?

One venue which pushed against the rules was the Dixieland Cabaret, which opened on Queen Street in 1922, near the corner of what is now Mayoral Drive. Three years later it moved to the beachfront of Point Chevalier, calling itself Dixieland By the Sea. The owner, Frederick Rayner, argued that after the restaurant closed, it essentially became a private party and so patrons were legally entitled to bring their own alcohol (as they would if attending a party at a person’s own home). Participants paid a sizable entrance fee and were then offered the opportunity to hire glasses for the evening at a cost of sixpence, which could at least partially be refunded at the end of the evening when the glasses were returned.

Article about the Dixieland, published in NZ Truth, 5 August 1926.

For a few years, big bands played and the alcohol poured freely, but finally in 1926 there was a highly publicised raid. Rayner and the venue’s manager were both taken to court and each fined a hefty £20 ($2222 in 2022 money), but the Dixieland avoided losing its licence. Cases such as this effectively set the stage for the unofficial approach of police from this point onwards: if a place seemed reputable, then the police would seldom attempt to make a bust.

Some venues simply turned a blind eye while others assisted surreptitious drinking, as in the case of the Majestic Cabaret in Wellington, which had long tablecloths and fake fireplaces with shelves inside, so bottles could be ferreted away if the authorities turned up.

The Musicians Ball at the Blue Domino venue with the Majestic Cabaret, Wellington, in 1956. Private events allowed attendees to bring their own alcohol. - Alexander Turnbull Library EP 1956 2210-F

Enforcement of the drinking laws was even looser for overseas soldiers stationed here. One favourite spot for US troops during World War II was the El Rey in Hillsborough, Auckland, which featured a house band playing Glenn Miller’s hits, with T-bone steaks on the grill, and beer for sale – despite Hillsborough supposedly being a dry area.

Even more influential on the local music scene was the Bird Dog Club in Christchurch, which was opened for US soldiers on their way to Antarctica in the 1950s and 60s as part of Operation Deep Freeze. Ray Columbus described it in his 2011 memoir The Modfather: Life and Times of a Rock ’n’ Roll Pioneer as being “like stepping into a beer hall in outback Arizona” and went on to explain how the music on the jukebox profoundly inspired both his band The Invaders as well as Max Merritt and the Meteors when they had the opportunity to play gigs there.

International air travel afforded New Zealand a new connection with the rest of the world and returning travellers would marvel at how archaic our alcohol laws seemed in comparison to many other countries. The temperance lobby remained strong, but in some ways it was more like the modern gun lobby in the US: the majority of the populace didn’t agree with their hard-line position, but they weren’t as politically active so the politicians were scared to rock the boat.

Those in the know still found it easy to locate a place where they could drink and listen to music. From the 1940s to the early 1960s, musicians in Auckland knew that they could turn up at the Polynesian Club on Beresford Street after they’d finished their paid work for the evening and be able to have a “blow” onstage, while the owner Lou Mati served beer from under the counter. Key figures from the local scene such as Phil Warren, Don Lylian, Bernie Allen, and Merv Thomas became regulars. The club kept a low profile by not advertising in newspapers and relied instead on word of mouth, essentially running as a speakeasy until a stabbing on the stairs saw the venue finally shut down.

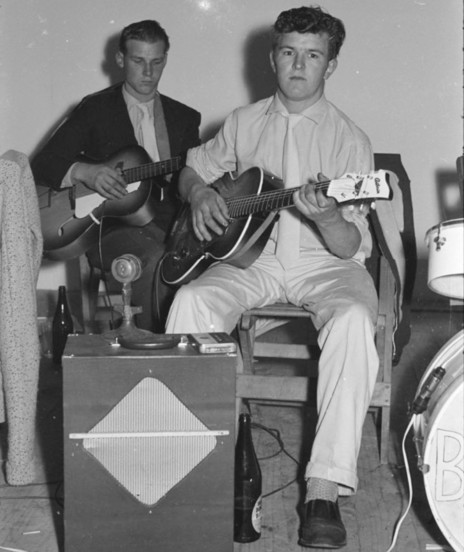

In the late 1950s, private parties were still the only places you could legally drink and watch live music. This 1959 photo shows the guitarist for The Bluetones with a bottle of Draft Dominion Bitter at his feet. - Auckland Libraries 1269-B0103-02

The Crystal Palace on Mt Eden Road advertised Merv Thomas and The Dixelanders, and special coffees served by “one who knows” for the drinker’s “comfort and stimulation” – code that they contained alcohol. Phil Warren was the promoter at the Crystal Palace and later told Roger Watkins:

“Our coup de resistance [sic] was that we had what was called the Bermuda Bomber ... [There were these] big plastic containers that you usually put orange in. We would tip Bacardi in and get rid of the bottles, then fill them up with Coke. We served them just like that. The police would have had to take them away to the DSIR to test the bloody stuff – to say it’s so much alcoholic content. So we opened and the place took off like a rocket. We had to turn people away.”

Dine and dance … and drink?

In general, musicians were safe enough if they played at established cabarets – perhaps bringing a hip-flask in their instrument case – but the situation was dicey at newer venues.

The 1950s saw the rise of the “dine and dance” restaurant where patrons would go for a meal and then dance into the evening. Unlike the light supper provided at dancehalls, these restaurants offered serious modern cuisine. Rather than formal orchestras they would have small bands playing more modern music.

Drinking to music at the Esplanade Hotel in Queenstown, 1971. - G. Hutchinson, Archives NZ R24802025

Dine and dance restaurants often got around the licensing laws by opening in locations that were difficult for the police to get to. In Auckland, this saw a series of live music spots open in Waitakere, including Back O’ The Moon, The Dutch Kiwi, Toby Jug, and Pinesong (though the latter often hosted private events, where drinking was allowed). A similar logic led to other out-of-the-way venues such as the Ranch House in Beach Haven, where customers came off the ferry with crates of beer, and The Pines in Wellington’s Houghton Bay, on the isolated south coast looking out over Cook Strait.

Evenings at The Pines would start out with relaxed music and a family-friendly vibe, but after midnight the liquor came out and drinking took place out in the open. Pianist Garth Young recalls that he was often pulled in to the shenanigans:

“Pat McCashin, the owner, would go around the tables with a beer glass and say, ‘Put something in for Garth.’ So it’d be whiskey, gin, vodka, all together: you name it, and I’d have to drink it. There was a fair bit of drinking involved.”

Garth Young (centre) raises a can of beer to his fellow musicians at The Pines in Wellington, early 1960s. From left, singer Mary Larkin, drummer Bruno Lawrence, Garth Young, and bassist Slim Dorward. - Garth Young collection

One of the earliest dine and dance restaurants to open in West Auckland was the Town and Country Roadhouse, which ran from 1948 to 1968. The son of the owners, Dave Harré later wrote (with his nephew Drew Harré) a book about the venue called Roadhouse Days (Little Island Press, 2009). He recalled that the restaurants nearby would call each other if the police were doing raids in the area:

“There would be panic. 10 or 11 years old I was sent upstairs, out through a window and onto the roof to lower the ‘Alcoholic Liquor Prohibited’ sign by its chains so it hung above the main entrance. The guests were warned to drink up or hide the bottles.” One musician to play at the Roadhouse was pianist Billie Farnell, who was asked to join the band there by drummer Phil Warren.

Farnell then moved to a residency at El Morocco in 1955 and found himself on the wrong side of the law when owner Leon Aldridge asked him to help hide the alcohol they were selling on site, as Farnell explained to the 2011 Queer Stories Our Fathers Never Told Us oral history project:

“We had a dumb waiter … It [brought] the food up and down into the restaurant. And Leon said to me ‘Oh god, take this’ and it was a box of Dewar’s Whiskey, a wooden box with all the drink in it, you know. I thought ‘What am I going to do with this?’ So, I stuck it in the dumb waiter, and I jammed it between two floors … the police were so angry they got an axe. They axed the walls … and Leon went to jail for three months for selling liquor.”

The police claimed that Farnell had been selling liquor and that he hid it in a compartment inside his piano stool. He presented the seat itself in court and proved that it had no such compartment.

As the 1950s progressed, dine and dance venues became increasingly upmarket. In Auckland, Otto Groen and Jim Jennings ran The Hi Diddle Griddle on Karangahape Rd, where lounge musician Paul Lestre recorded an album in 1959, with Jennings providing a spoken word intro.

This new style of venue brought musical performance and dining closer than ever before. The chefs and the musicians provided the drawcard for customers, though the inability to sell wine to complete the experience was something that frustrated the owners. Jennings even printed a wry comment on the Hi Diddle Griddle menu:

“Let us hope that those of us who appreciate a fine wine with our meals can induce our government to do something about making this possible … after all, those who do not favour wines need not partake, the food is still good.”

In her book Dining Out: a History of the Restaurant in New Zealand (AUP, 2010), Perrin Rowland describes the myriad ways restaurateurs had of getting around the laws of the time:

“The Gourmet [in Auckland] used to set each table with glasses already filled with ice. If the police came in, they were water glasses; if not, customers simply filled them with whatever they brought with them. In Christchurch, diners at the Milando would find their wine bottles corked with candles if owner Hans Levy got wind that his restaurant was about to be raided. Customers also dropped off their ‘supplies’ for the evening when they made their reservations. Orsini’s [in Wellington] kept private cellars for regulars: customers would walk in with their bottles and these would be labelled and kept in the back of the kitchen to be served with their meals.”

A cabaret against licensing laws held in the Sapphire Room of Otto Groen's restaurant, The Gourmet, Auckland. The bass player is George Campbell, the comedian Barry Linehan. Photo: Otto Groen Estate.

Jennings and Groen opened a highly influential restaurant, The Gourmet, in Shortland Street, Auckland. It hosted a cabaret show mocking the alcohol laws. Groen toured the show throughout the country and funded a run of flyers and cartoons protesting against the laws. The Gourmet was repeatedly fined, but Groen finally got his way when the law was altered in 1961 to allow wine to be sold with dinner until 10pm. Female staff were now allowed to work in bars. The Gourmet received one of 10 licences that were handed out nationwide in that first year.

The number of licences increased the following year, but by 1964 the number had only reached 44 as the application process was drawn out and expensive. The situation worsened the following year when new legislation introduced onerous requirements for restaurants before they could be licensed. For example, specifying how many coat hooks had to be at the front door, and the floor-space per customer.

Meanwhile, there were plenty of other types of music venues that had no interest in selling alcohol. When rock’n’roll arrived, it found a new teenage audience who attended shows at halls throughout the country. One club in Auckland, The Beatle Inn, banned entry by people over 21. The young age of the rock’n’roll audience meant drinking wasn’t usually foremost in their minds. Ian Hughes, who played in the Tornados in Wellington, recalled:

“We played private parties and weddings and there was always alcohol at those, but as far as the teenage music scene there was no alcohol available and there were youth clubs everywhere – places like the Lower Hutt Youth Club, Eastern Bays Youth Club, and The Porirua Youth Club. Virtually every suburb had a youth club, there was nothing else for teenagers to do.”

It was only when Hughes moved to Auckland and started playing cabaret venues as a member of The Village Gossip that he noticed audience members heading outside to drink in their cars.

Cabaret floor shows were late-night entertainment for adults only, and could feature top acts such as Ricky May and Marlene Tong, so if some patrons happened to discreetly bring in a bottle of wine it usually wasn’t seen as a problem.

Ricky May performing at Bob Sell’s Colony nightclub in 1961, upmarket enough that patrons felt comfortable having their own bottles of alcohol out on the tables. - Auckland Libraries, Rykenberg Collection, 1269-E164-10

However, there was a scene halfway between the predominantly teenage rock’n’roll dances and the predominantly adult cabaret scene. Coffee lounges around the country also opened at night and picked up on new styles of music, from jazz to rock’n’roll. Dave Williamson was a working drummer in this scene during the 1960s:

“There weren’t too many patrons who were what I would class as ‘always drunk’. Maybe happy and very loud, but not too over the top. I know about 15 percent or even 20 percent used to hide a small bottle of ‘something’ to mix in with other beverages, like Coke or lemonade, etc. I do remember however, when playing at the Picasso Coffee Lounge (Auckland), local and overseas sailors used to arrive absolutely ‘plastered’ and I saw many fights there. So many in fact, that I moved my drum-kit closer to the kitchen, to be able to take cover if a rumble started. After one violent fight on the street, one drunken sailor was kicked back down the stairs from the entrance! (so that’s what they did with the drunken sailor!).”

The inability to buy alcohol in coffee lounges and folk clubs in the 1960s created an opening for an illegal trade to develop. In Joanna Mathers’ book Backstage Passes (New Holland Publishers, 2018), Faye Reid from the Fair Sect recalls one notorious sly grogger named Happy Jack who sold alcohol hidden in his coat at Embers nightclub: “He’d open up his coat and have quarter bottles of vodka and bourbon tucked away, which people would mix with the Coke they sold inside.”

A new era begins

As the 1960s progressed, the untenability of the current alcohol laws finally became apparent. In particular, the vile state of public bars was a national embarrassment. Any pretence of civility had been entirely lost and participants in the six o’clock swill would enter bars that had no stools to sit on, no food for sale, and no entertainment aside from swigging beer as quickly as possible. The situation had become so bad that some publicans were caught taking leftover drinks and pouring them back into the line. Rather than curbing alcohol’s ruinous effects, the laws were instead nurturing a culture of binge-drinking.

In 1967, the New Zealand Government finally decided the time had come to ease alcohol laws. Closing times were pushed back to 10pm and the ban on entertainment in pubs was lifted. Two years later, the drinking age was lowered from 21 to 20 years old. Yet it was still difficult to gain a licence and for an application to fail it required only 20 people to object. Initially, a reason was required, such as proximity to a school or church, but in 1953 it was broadened to include any qualms a nearby resident might have.

Paul Lestre (violin) and Oscar Huijisse snr (piano) at the Cafe de Budapest in Remuera in 1967, while the owners Gabor Csongor and Bela Demeter enjoy a drink with their meal. Auckland Libraries 1269-05-04

The historic laws requiring pubs to be attached to accommodation had been lifted in 1961, but due to the difficulty of new entrants coming into the market, it was no surprise to find many of the most active music venues over the next couple of decades still fitted the bill: The Rising Sun Hotel and the Mon Desir Hotel in Auckland; The Empire Tavern/Hotel and Captain Cook Hotel in Dunedin; Hotel Cabana in Napier. Researcher Petra Smith suggests these hotel bars were actually well set up to have musical performances:

“Six o’clock closing impacted the architecture of hotels. Most hotels built pre-1917 eventually knocked out internal walls leaving one or two fairly cavernous spaces, with very little sit-down furniture. Maximum floor space and sight-lines, with a bar set up with hoses and jugs to minimise queues, is a good mix for an economical moderate-sized venue.”

Diners dancing in 1971 to a DJ at John's Place, a discotheque and restaurant nightclub in the Rialto Arcade, Newmarket owned by John Blackwell. - Rykenberg Photography, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19710522-05

Dave Williamson played the Milford Marina Hotel with guitarist John Willetts in the late 60s, but found it a downgrade from the clubs and coffee lounges he was used to. “The audience was far less attentive, as they really only wanted to talk and drink.”

Many of the taverns throughout the country were tied to one of the big breweries or even owned by them outright. New Zealand Breweries (renamed Lion Breweries in 1977) decided to set up its own touring circuit of bands so that it could further control the revenue of these bars, as Nick Bollinger describes in his book Goneville (Awa Press, 2016):

“The Breweries circuit hosted covers acts, showbands, and faded offshore entertainers such as Eddie Calvert, [so] original groups were forced to create their own circuit: provincial halls, university campuses, unlicensed clubs, occasional festivals, street parties.”

Tapestry in Brew News, December 1972.

New Zealand Breweries even went so far as to set up its own bands with alcohol-themed names such as Beam (after Jim Beam), Distillery, and Pilsner (a band brought in on contract from Wales and renamed), as well as polished covers bands from the Philippines such as The Constellation and Royal Flush. (This fascinating story is covered by Keith Newman in AudioCulture’s On the Road: the Pub Circuit.)

At its height, the National Entertainments Manager at New Zealand Breweries, Richard Holden, controlled a budget of $2 million dollars per year ($22 million in 2022 money). He wanted jukebox bands playing the hits; original songs were discouraged. As Nick Bollinger wrote, Holden’s gruff philosophy was “We’re not in the genius business.” It wasn’t until he left the position in 1977 that the situation loosened and new players such as Mike Corless and New Music Management were able to gain a foothold.

A New Zealand Breweries ad in Auckland Star, 9 April 1974. Legitimate acts such as Creation and Tuhi Timoti’s Cricklewood feature along with the brewery-formed band Distillery and Australian import Big Norm.

For the most part, it was venues with a long history that found it easiest to hold a licence during this period, trading on their previous reputation. This became particularly important after the introduction of “cabaret licences” in 1971, which allowed a small number of venues that served food and offered entertainment to stay open until 11.30pm.

One of the most important venues, Mainstreet in Auckland, had a long history of dancing and surreptitious drinking. The upper Queen Street location was first opened in 1938 as the Metropole, and in 1952 it was renamed the Peter Pan Ballroom, after the original Peter Pan moved up from Rutland Street. The Peter Pan was an upmarket ballroom and had no problem gaining a cabaret licence. When Tony Lipanovic took over the venue as Mainstreet in 1978, it seemed at first that it would continue in a similar style, but he soon realised that modern rock and overseas touring acts would be a much bigger drawcard and quickly switched tack.

When new licensed venues did appear they were often set up as suburban “booze barns” where music was a background consideration rather than the central attraction. Promoter Ian Magan later suggested the loose drink-driving laws of the time meant these out-of-the-way venues could still draw in the punters:

“In those days you could go to the pub, as we did, for two hours every night and drive home happily. Obviously that encouraged the big barns like the big pub called the Thunderbird Valley Inn in Glenfield which held around 1800 people. So you’d jam them in there – bands like Tommy Adderley and The Chicks – and have a bloody good night.”

The drink-driving laws had changed in 1969 to make it illegal to drive with over 100 milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood. However this was twice the 2022 limit and meant that an adult male could drink a full six-pack of beer (or four pints) over a couple of hours and would most likely remain legal to drive. What’s more, there was no easy way for police officers to test a driver’s alcohol level at the roadside so they had to decide whether it was worth taking the person back to the station for a blood test. This situation continued until 1984, when breath-testing became available.

Start spreading the Newz: the Aranui Motor Hotel, Christchurch, outside and inside. Photos: Rockhappenz, Rob Mayes

Independent operators continued to struggle with alcohol laws throughout the 1970s. Tommy Adderley and Dave Henderson went without a licence in 1971 when they started the Granny’s venue in the old location of Bo Peeps/The Top 20 in central Auckland. At first, patrons would buy alcohol out of the boot of a car parked outside, which they’d bring into the club. The pair then opened Granpa’s upstairs as a private club, thinking this would allow members to drink freely, but the police were not impressed. Over three years in business, they amassed fines of $15,000. Adderley was bankrupted, losing his car and his house in quick succession.

Phil Warren also continued to battle against liquor laws and racked up huge fines as a result. He believed there was a loophole in the law which would allow him to sell tickets at the front door of his club The Crypt, which patrons could exchange for drinks inside. The authorities fined him regardless, though he did succeed in helping to push cabaret closing times back to 3am (from 1977 on). Warren’s interest in changing the laws drew him into politics and he became deputy mayor of Auckland in 1988.

Music promoter Phil Warren (fourth from right, waving) and friends at the Peter Pan Cabaret in 1963. Photo: Phil Warren collection.

Unlicensed venues continued to be popular during the late 70s and early 80s. Desna Sisarich helped run Ziggy’s in Wellington from 1973-76, but told AudioCulture it was tough to survive without income from alcohol sales:

“Ziggy’s was not licensed. We had a ‘locker’ system, which the police were aware of. Malcolm George and I would physically carry all the crates of drink-mixers up a huge flight of stairs (no lifts) in our lunch breaks from our real jobs.”

New punk and post-punk venues that followed in the late 70s had no chance of gaining an alcohol licence so most didn’t even bother trying and let patrons bring alcohol or not as they pleased. This included influential spots such as Zwines, XS Café and Squeeze in Auckland; Thistle Hall, The Last Resort, and Billy The Club/Rock Theatre in Wellington; Mollett Street in Christchurch; the old Beneficiaries Hall in Dunedin.

The drinking age at that time was 20 years old, and heading into the 1980s teenagers still needed somewhere to see bands. Sometimes this led to innovative solutions, as with the Powerstation in Auckland, which would occasionally keep the bottom floor as all-ages and alcohol free while the top floor was licensed. Lorde tried to repeat this in the 2010s, but her application was rebuffed.

Alcohol, music, and the modern world

The next big step in the story of licensing laws in New Zealand was the Sale of Liquor Act 1989. The rules for opening new bars or licensing restaurants were lifted and closing times of bars were put into the hands of local authorities. Licensed venues could now open until the wee hours of the morning.

Simon Grigg was the owner of Siren, which would soon become Box/Cause Celebre and already held an all-night licence through a historic quirk of the law. He found that staying open all night was a double-edged sword:

“Club Mirage (Siren) was the old World War Two US officers’ club so we had the only 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year licence in New Zealand. It was great. We could open on every day of the year including Good Friday and Christmas. So we did. We did huge business on those days. The 1989 act cancelled all existing licences so we had a standard one thereafter. It lost us money. We had always closed at 3am even though we were allowed to open but the new law meant that everyone opened all night so we had to as well. It made no difference to our bar take and hit our profits as nobody drinks much after 3am. So, more wages and no more money.”

Another headache for Grigg was the change in driver’s licences which made it easier for underage drinkers to game the system. Plasticised-paper driver’s licences had been introduced in 1986 and the following year a three-tiered system of licences (learner, restricted, full) was set in place, which inadvertently led to them being abused as a form of age identification. While most drivers needed to keep their full licence at hand, a younger sibling could get hold of an old learner’s or restricted licence from their older brother/sister. Underage forgers did their best to alter their own licences to show the necessary age.

This strategy was often used in order for underaged people to see live acts play, as the music scene had become firmly wedded to licensed venues. However, there was a reaction to this situation. The hardcore punk scene in Auckland and Hamilton during the 90s was filled with “straight edge” bands that refused to play bars, instead echoing the rock’n’roll years and booking halls and other hired spaces to put on shows.

In 2022, the New Zealand Music Commission tried to encourage more young promoters to put on all-ages gigs by producing an informative zine, Gig Starters: A Guide To All Ages Music Events in Aotearoa .

The need for this movement was reduced in 1999 when the drinking age was lowered to 18 years old (and hard plastic driver’s licences were introduced that showed the owner’s photograph).

Since then some venues have still been keen to promote all-ages and licensed gigs by having an early show with no alcohol available followed by a regular bar show later in the evening. Notable examples include the Masonic Tavern in Devonport, when Boyd Thwaites was manager (and The Checks were in ascendance), and the brief reign of Puppies bar in Wellington, which was run by Ian Jorgensen/Blink, the promoter of the all-ages A Low Hum festivals.

In 2013, there was a new attempt to limit the consumption of alcohol when bars and clubs were compelled by law to close between 4am and 8am.

The all-ages scene remains a very small part of the music industry, and temperance campaigners of the early 1900s would be horrified to see how far things have gone in the other direction. There will undoubtedly be future changes to licensing laws that have an impact on the live music industry, but having a drink while watching a musical performance remains an accepted social norm in New Zealand.

--

Further reading

Online

Te Ara: liquor laws

Te Ara: nightclubs

Books

Blue Smoke: the Lost Dawn of New Zealand Music 1918-1964 by Chris Bourke (AUP, 2010)

Dining Out: a History of the Restaurant in New Zealand by Perrin Rowland (AUP, 2010)

Goneville: a memoir by Nick Bollinger (Awa Press, 2016)

Backstage Passes by Joanna Mathers (New Holland Publishers, 2018)

Grog’s Own Country by Conrad Bollinger (Minerva, 1967)

Removing Temptations: New Zealand’s Alcohol Restrictions, 1881-2005 by Paul John Christoffel (available here)