In May 1969, ably guided by photographer Max Thomson, Playdate’s by-no-means indefatigable reporter caught Auckland’s late shows in four city nightspots: Mojo’s, Embers, Montmartre and Bo Peep.

Mojos, corner of Queen and Rutland Sts, Auckland 1969.

Mojo’s, Rutland Street

“The Soul Scene” – Mojo’s is not a haunt for theology students. Matt black, red lights glowing, thundering noise: although it is upstairs, Mojo’s is no celestial scene. In the dimness, walls and ceilings seem to recede and the patterns painted on the walls in luminous colour are thrown into relief. Art Nouveau flowers and a great blank-eyed head echo Beardsley and hippie revivals of all that is decorative and sensuous, with hints of decadence and mysticism – dark areas of the mind, nocturnal Byronic muses …

But the darkness is rent by flashing lights, rainbows exploding like shells, and the poetry is not lonely and introspective but the communal shouting of Black Culture winning in the competitive world of 1960s pop. Soul is celebration of feeling – emotion paraded to the big beat. But now is not yet soul-time. Now is the time for drinks and conversation, the rumble of audience talk before the floor show. An audience which is expectant. A good atmosphere if you are waiting in the wings ... In Mojo’s there are no wings. The dressing room is squeezed into a tiny space behind the stage, and if the stage resembles a four-poster, the dressing room is a wardrobe in the back corner of the bedroom.

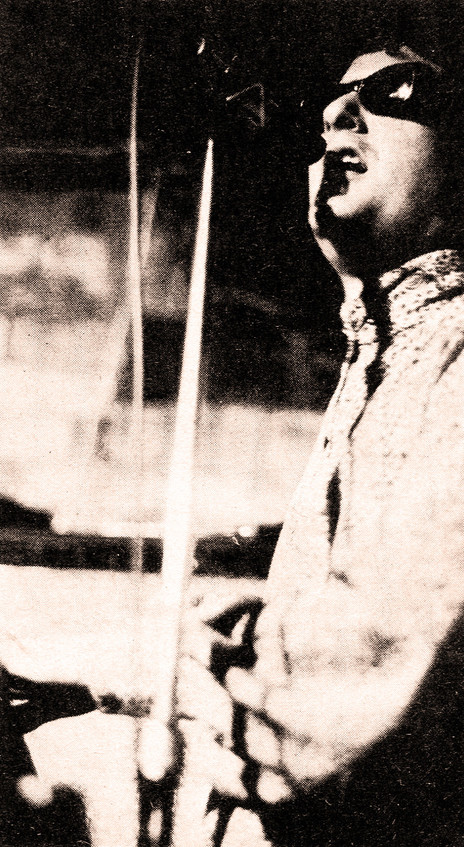

Sonny Day joins the Chicks onstage at Mojo's, 1969.

The announcement of the floor show is “voice over.” You await a focus for the eye. The resident band (Brian Henderson, Jimmy Hill, Dave Russell) are at their places, but the front of the stage is conspicuously empty as The Voice apologises for the absence of a quarter of the show (Tommy Ferguson is billed but has been delayed at an engagement on the North Shore) but introduces The Chicks and Sonny Day.

The Chicks waft down the narrow passage and on to the stage. Day follows them, in a creditable performance of the “run on” where there is no room to run. The Chicks are resplendent in their costumes, all filmy and light. Day is a new Day to the one I remember: Mexican moustache, shorter hair, and wearing double breasted coat with prominent buttons and a brave red handkerchief.

My metaphor longs for the Chicks to open with ‘Angel of the Morning’, and I remember the movie Damn Yankees with Ray Walston’s red tie and sox identifying him as the Devil. But the Chicks – they’re no angels, and Day is no Devil. Soul singers all! The Chicks are a fine double. Songs of innocence and experience. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Dark and light. The two girls have a terrific complementary quality, look as well-paired as they sound. The old precision teamwork has been abandoned here for a free-wheeling dance, and in the absence of Ferguson it is not easy to evaluate the effectiveness of teaming the Chicks with Day. A triangle lacks balance. But the three make a good professional showing.

The courtyard at Embers, Auckland 1969.

Sonny Day has improved immeasurably. He has dash now, seems to revel in his new image, that big grin beaming happy beneath the moustache, and the facial grimacing not too serious as he “emotes”. The bracket opens with ‘Make the Feeling Go Away’, shifts without pause into ‘I Know A Place’, races on to “Play It Again,” and credits the Temptations (chalk one up for the metaphor) before “I’m Gonna Make You Love Me.” Highlight is a vibrant and vital rendition of Joe South’s hit ‘Games People Play’.

Without knowing anything about arrangements and presentation rehearsed for a quartet, it is impossible to say how much the three missed Ferguson. Enough said to credit the Donaldson girls and Sonny Day for an energetic and lively turn. And the boys in the band – thanks for a solid sound. The audience is appreciative and demonstrative – Mojo’s cramped quarters have always made for good rapport between artists and audience. The atmosphere is, if not electric, at least charged with excitement and life. And the light show – a really dazzling spot, plus “in time” flicker and a continuous variety of colour and intensity – maintains an overall “happening” quality. As far as the “soul” content goes: it is just “pop” for my money, I can’t take the “emotion” all that seriously. But this floor show was good pop all right, belted out with confidence and (can I bend meaning to metaphor again?) spirit. The band is spirited too. We stay for two numbers – “Uptight Outasight” and “Bread and Butter” – and the small dance floor is packed within moments.

That then was Mojo’s: a “soul scene” to uplift by means of unlimited energy, solid professionalism and a close bond between audience and entertainers.

Embers, Chancery Street

By the clock it is already Sunday as we sit in Embers listening to Shelby Grant and Frank Hay. After Mojo’s dictated excitement and unabashed effort, Embers is noticeably “cooler”. Decor is less deliberate: one wall exposed brick, another natural wood, like a compound fence almost. And the music is “emotionally neutral” – folk orientated now – ‘More Pretty Girls Than One’, a Lonnie Donegan tribute via ‘Cotton Fields’. Then Frank Hay makes a deadpan intro of a number “composed on stage by Mr Shelby Grant.” The title is guesswork: ‘Everybody’s Making It For Themselves’ or ‘What You Gonna Do About It Now?’ The duo finish with this, murmur that they will be replaced …

Embers sign, 1969.

The understatement works for me, as does their “straight” but satisfying musical presentation, but this Embers’ audience is clearly in tune with an understatement of their own. Grant and Hay leave the stage without any sign of audience recognition. Frank Hay converses with our faithful guide, is introduced as an ex-member of the Human Instinct (The Four Fours). He talks about how another ex-member has stayed in Britain, setting himself up as a “group transporter”. Dave Hartstone supplies (for hire by touring groups) a van fitted out with amps etc. Bookings in Britain can involve groups in travelling to up to 15 or so gigs per night. Efficient management and organization is a must in a competitive pop market.

If I digress, it is simply to indicate that after Grant and Hay quit the stage there is quite an interval before the appearance of the next act, Claude Papesch’s group. At Embers there is a complete lack of urgency. Papesch reaches the stage, impresses with his calm, unhurried walk to the organ. His blindness is theatrically effective – it is hard not to be impressed by the authority of his presence. He is a big man, and unhurried, like a westerner. He fiddles with knobs while the crowd waits. Not that the crowd is restive. Mojo’s was a “go-go” crowd, their talk louder, their attendance “purposeful.” At Embers crowd and artists are divorced; each gives the impression of being self-contained.

Claude Papesch at the Montmartre, 1969

Papesch is satisfied. Bruno Lawrence on drums and bass guitarist Tim Piper are ready. The Cat Stevens album fill-music is cut. (Mojo’s had a soul album in briefer service.) The group launches into ‘Conquistador’. (Remember Procol Harum?) If Mojo’s resident group delivered a big sound, Papesch’s is gargantuan. There is no “floor show” here; the music is not an act designed to claim the visual attention. The sound booms. The dancers move to the floor; it is small, as was Mojo’s. The next number is ‘Don’t You Say A Word’ and the third ‘Cincinatti Woman’.

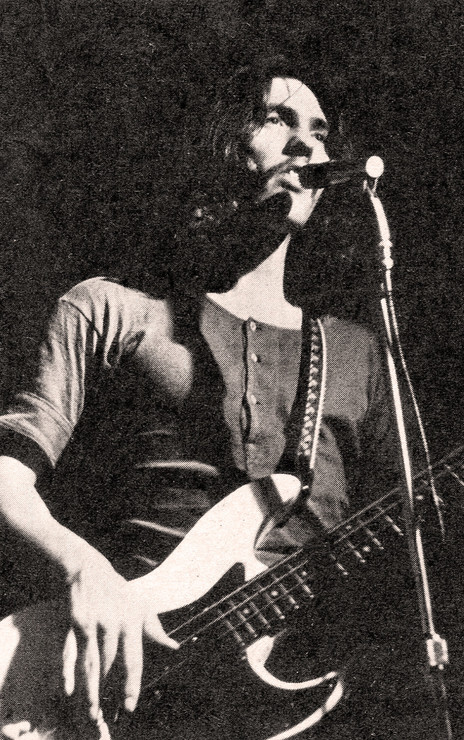

Tim Piper on bass with Claude Papesch's group, Mojo's, Auckland 1969.

The Papesch group is a mighty trio, their sound full and their understanding impressive. Claude seems to be dissatisfied, makes repeated adjustments to the amp settings, but the trio sounds fine. (They look good too: Tim Piper’s faded singlet is worthy of Fleetwood Mac.) The three musicians seem to enjoy making music – pop with a weight and virtuosity to satisfy even the critical. The dancers have some “high-society” qualities. If sophistication equals “cool”, the Embers crowd are the most sophisticated encountered in our brief tour. They support Embers by attending, signify approval that simply, as if there was no point in additional applause or enthusiasm.

As with Mojo’s, Embers has the club attribute of being a recognized meeting place; many here are habitues. Embers’ appeal is more subtle than Mojo’s’ blatant excitement, the “cool” possibly an acquired taste.

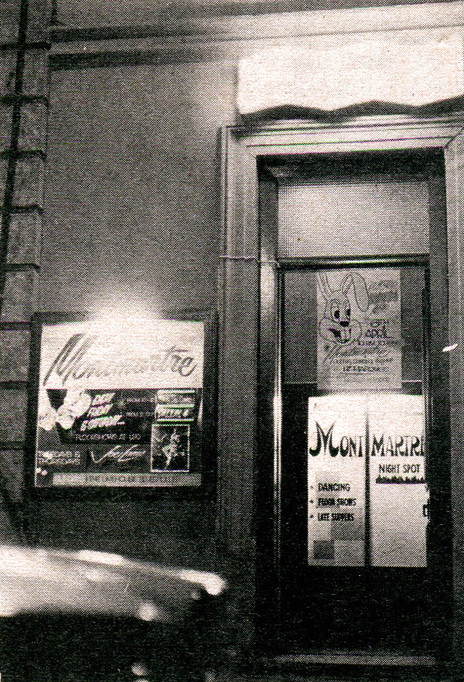

Montmartre, Lorne Street

Montmartre is advertised with an eye to drawing the “sophisticated” audience. In keeping with the name, the nightspot is decorated to suggest Montmartre in the era recorded in Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings. There is a very successful mural after the style of Lautrec, and also posters in reproduction. The red lanterns are in keeping with the design, but the effect is outweighed by the canopy which weighs down upon the stage – perhaps the new management will dispense with this, and discipline the posters outside, so that a sophisticated atmosphere is complete.

Montmartre, Lorne Street, Auckland 1969.

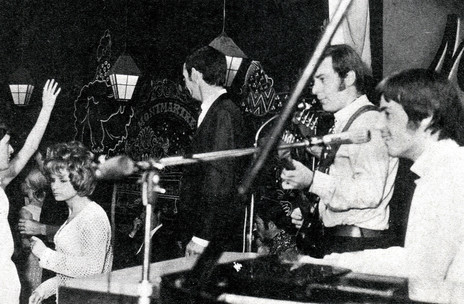

The Dallas Four have established a distinctive style which promises to give Montmartre the identity it seeks. Theirs is a sophisticated brand of pop, albeit a versatile one. As a resident group they supply lively, danceable music, but it is in the floor show section of their night’s work that the Dallas Four are showcased as an outstanding quartet capable of fine harmony.

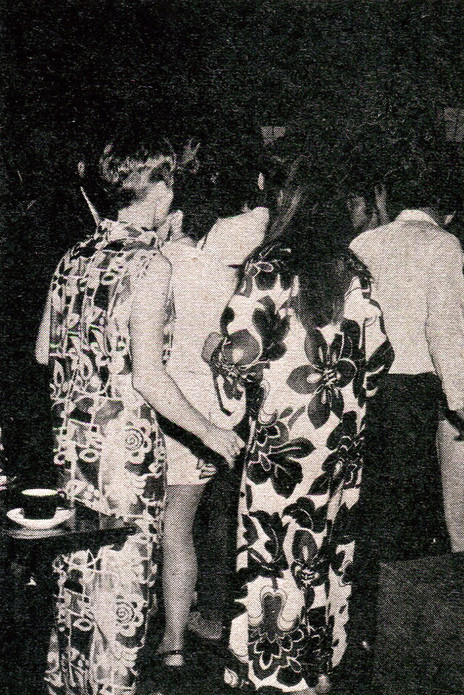

Dancers at Montmartre, Auckland 1969.

In their introductions they credit groups such as the Lettermen and the Happenings, and it is this kind of smooth, soaring and elaborate interplay of voices and instruments that they recreate so successfully. Fashions and fads in pop come and go, but harmony singing is never long eclipsed. From the Crew Cuts to the Four Preps, the Mamas and the Papas to the Fifth Dimension, sweet music has found avid audiences. The Dallas Four have this timeless appeal.

Keith Adams introducing the Dallas Four, Montmartre, Auckland 1969.

The Montmartre audience loves their thing. ‘Goin’ Out Of My Head’, ‘My Mammy’, ‘Excerpt From A Teenage Opera’ – the source material is various but the formula is standard – harmony, first to last. If this is your kind of pop, Montmartre is your kind of club. Only flaw in the harmonious impression the Dallas Four create is their attempt at “sophisticated” humour in “adapting” the lyric of ‘Teenage Opera’ to get what can only be described as a cheap laugh. Blue humour is the quicksand that has claimed many a sophisticate’s popularity – and once lost in this way popularity is hard to regain. But one line in doubtful taste cannot discredit a very capable group.

Bo Peep, Durham Street West

Bo Peep is the spot for the young. Paradoxically, it is very sophisticated. Resident band, The Human Instinct, is in action as we arrive, but because the stage is at the entrance end of the long narrow room, attention does not beam in on the entertainers (who are assessed quickly, in passing) but on the audience. They crowd the dance floor and, beyond the floor, pack the seating area. (In none of the spots was there room to seat more. Signs that Aucklanders appreciate the nightlife now offering.)

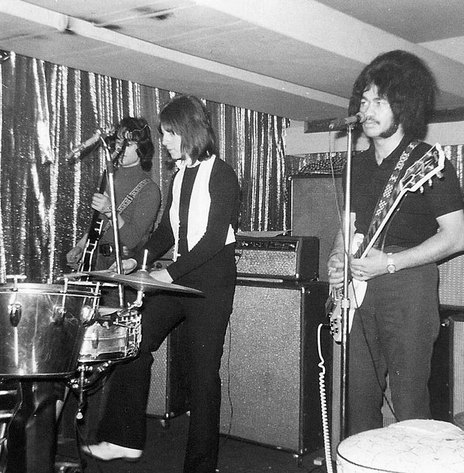

The Human Instinct at Bo Peep, Durham Lane, Auckland, 1969: Peter Barton, Maurice Greer, Billy TK.

The dancers in Bo Peep are a joy to see. All different, they display the variety show that is today’s fashion. There are girls here who look like natural, windblown beach beauties; girls who look like models; girls who look like careless hippies; send-up mod girls just like crazy Joanna [in the 1968 movie]; girls in ruffles, girls in florals; hidden behind wild-eyed make up; fresh faced … some are barely teenagers.

The teenage revolution has been won. Not because these “children” are free to be out at this hour of the night, but because they are free to differ so extravagantly. Girls and boys alike are knowing in matters of fashion, but fashion is wide open. There are no teenage uniforms here. Hair styles and clothes, makeup and self-concepts are displayed in profusion. Displayed is the word. These are self-conscious selves, but glorying in their individuality.

At the same time they are very obviously “a generation”. None of the other spots has such a clearly defined “style”. These kids have their own country and your passport to it has expired if you are older than … what, 21?

But, to leave the Bo Peep patrons to their own devices, a look at the spot itself. One wall is of natural rock in large blocks, each block painted a pastel shade. It sounds like a bad nursery (and who could defend the thinking behind painting natural stone in pastel paints?) but the wonder is that it works, somehow. The seating area beyond the dance floor looks as posed as a still from a 1960 movie, The Subterraneans. (It was about beatniks, another generation.) These kids are much more frivolous. Or so it appears.

On stage, the Human Instinct is another trio. The fantastic drum kit of Maurice Greer dominates the stage. Greer has a Brian Jones look, and a cheerful vocal style, as well as a strenuous stand-up drumming technique. Lead guitarist Billy Te Kahika and Peter Barton look right for a young group, but it is Greer who is the focal point, the crowd-winner. They play recent Top 20 material – ‘I Started A Joke’, and punchier things – ‘Midnight Mover’. Good, bright, loud music. The dancers are wild, jumping with energy.

Not us. After four spots we are quite willing to leave them to it. They say some will stay here until it is time to go home for breakfast. We need bed first.

--

Read more: Auckland, 1969: Around the Halls on Saturday Night

Link: Mapping Auckland Venues, the 1960s

Nga Taonga link: RNZ's Spectrum talks to Phil Warren, Rainton Hastie and Lew Pryme about Auckland nightlife, 1973.

--

After five years as the assistant editor of Playdate, in 1972 Tom McWilliams joined the NZ Listener, where he had a long career as executive chief sub-editor and occasional film critic.