A line-up of past Silver Scroll winners, 2003

Searching for the Lost Scroll – the idea sounded like a film starring Indiana Jones. Instead, it was the initiative of the songwriters’ collection agency APRA to correct a blip on its honours board for the best New Zealand-written song of the year. In 1981, due to administrative changes rather than riots in the streets, the Australasian Performing Right Association didn’t award a Silver Scroll – despite it being a breakthrough year in New Zealand’s pop songwriting.

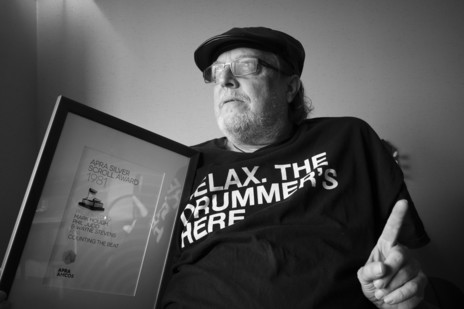

Buster Stiggs - Mark Hough - in September 2015 with the APRA certificate for The Swingers' 'Counting the Beat' when it was belatedly awarded the 1981 Silver Scroll. - Stuart Page

In 2015 the 50th APRA Silver Scroll took place, so naturally there was more concentration on history than usual in a contemporary music event. As well as the awards for the 2015 Silver Scroll – and for writing in contemporary, Māori, and film music – contenders from 1981 were chosen by APRA to compete for the “lost scroll”. The 1981 finalists would stand out in any year: ‘Counting the Beat’ (Judd-Stevens-Hough; recorded by The Swingers), ‘Tally Ho’ (Scott-Kilgour-Kilgour; The Clean), ‘One Step Ahead’ (Neil Finn; Split Enz), ‘There is No Depression in New Zealand’ (McGlashan-von Sturmer; Blam Blam Blam), and ‘See Me Go’ (O’Neill-van der Fluit-Drumm-Landwer-Johan; The Screaming Meemees).

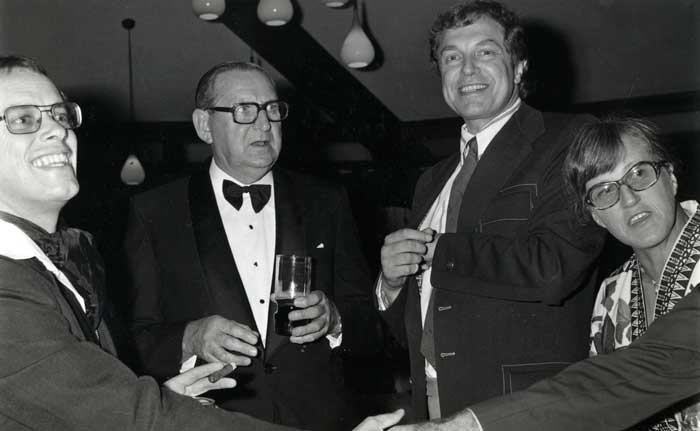

The first New Zealand convention of APRA, Wellington, 1957. New Zealand composers at the dinner are, from left: Llewelyn Jones, Larry Pruden, Thomas Gray, Doris Sheppard, Douglas Lilburn, David Sell, Thomas Powell, Vernon Griffiths, David Farquhar and Ashley Heenan. Larry Pruden collection, ATL.

The Silver Scroll is a songwriting award, not a record award: entries need to have been broadcast, but it is not about the quality of the recording or performance. Theoretically a demo of a great song, if broadcast, could win. The interpretations of the finalists reinforce the idea that a song is an entity, that it’s something others will want to sing.

In 1965 the APRA Bulletin noted the strength of composition in the fields of “light orchestral music and modern serious composition”. As an aside it also mentioned, in both Australia and New Zealand, an “upsurge in activity also occurs with popular music”. The Australian hit parade in particular showed a large proportion of pop songs were written by APRA members.

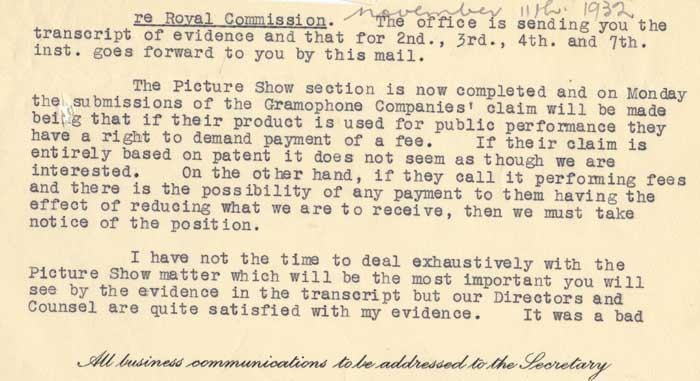

A 1932 internal APRA memo on the desire to charge performance fees to cinemas

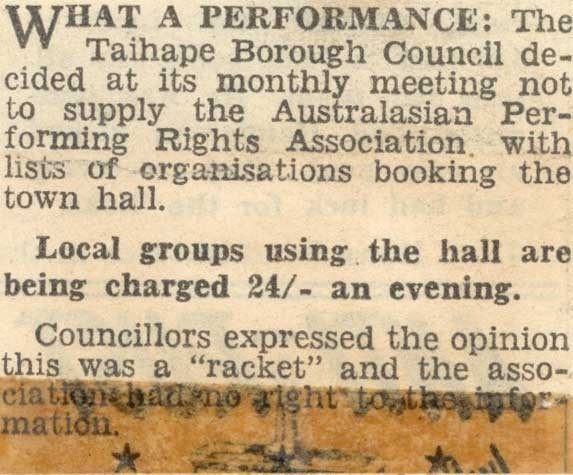

From the NZ Truth, July 1956: The Taihape council decides not to pay performance fees, describing them as a "racket"

APRA was formed in 1926 – almost immediately opening a branch in New Zealand – to collect composers’ royalties from airplay and other sources (eg, music played in restaurants, sporting events). But in its public profile the emphasis was on the “light orchestral music and modern serious composition” side of its activities rather than the popular music that brought in the bulk of its income. So its publications from the 1950s and early 1960s note new pieces by composers such as Douglas Lilburn (a very dedicated APRA member), David Farquhar, Jenny McLeod and Larry Pruden. As the New Zealand writers’ representative on the board, composer Ashley Heenan was especially prominent until Ray Columbus took the role in 1980. (Columbus was succeeded by Arthur Baysting in this “writer-director” position in 1992, and the baton was passed to Don McGlashan in 2013).

One of the rare "pop" writers on the books of APRA in 1961, Tony Eagleton from Tony and The Initials is pictured here in The Dominon assigning a song to the association.

An era of change at APRA New Zealand began in 1965. Bert Rolfe retired as the New Zealand manager after joining the staff of APRA in 1926 – the year it was founded in Australia. He transferred to New Zealand to open and run its office in 1927. At the time, the fledgling radio industry resented paying any copyright holders for music they broadcast, and the Government supported this stance with a law that was on the statute books for a year. But lobbying by APRA changed this, and since then composers have had to be paid for the public use of their music. Reluctance by some café and gym proprietors has not changed in the nearly 90 years since.

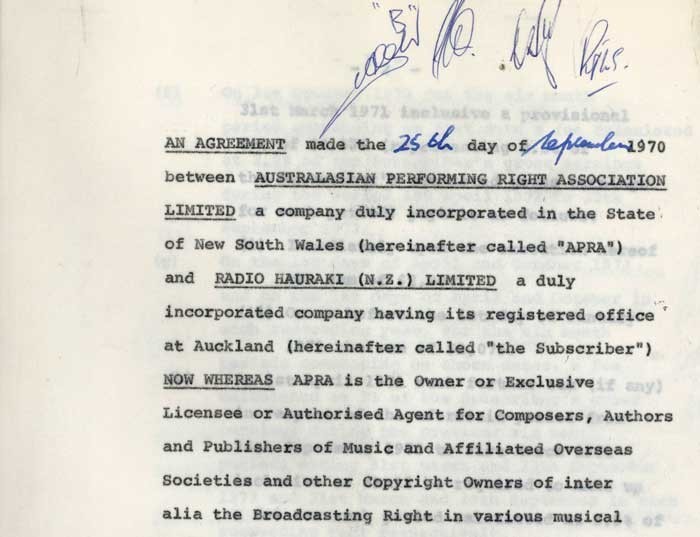

By 1970 all media were required to have an APRA licence. This is the first Radio Hauraki contract signed by a newly legalised station.

Rolfe spent his early days in New Zealand as jack-of-all trades: he went to silent movies and wrote down the melodies played by the live orchestras, he had to deal with an irate café owner brandishing a knife, and he hired bicycles to visit clients around the country. The main local recipients of APRA income were what Alfred Hill (‘Waiata Poi’) called “dicky-bird composers”, who earned 10/6d a song from the National Broadcasting Service.

After hours Rolfe played violin in a restaurant trio, so APRA’s emphasis on “serious” composition is more a reflection of the hegemony of the cultural elite than Rolfe’s own tastes. Since colonial times, there has always been plenty of popular songwriting in New Zealand, with 1887’s ‘On the Ball’ by Ted Secker being our first international hit. But for decades the field was dominated by amateurs, until the emergence of writers such as Ruru Karaitiana (‘Blue Smoke’) and Ken Avery (‘Paekakariki’) after World War II, when a local recording industry got underway. With New Zealand records being made in New Zealand, they were finally being played regularly on local radio – so royalties needed to be collected by APRA.

The announcement of the first Loxene Golden Disc and APRA Silver Scroll in The Dominion, September 1965

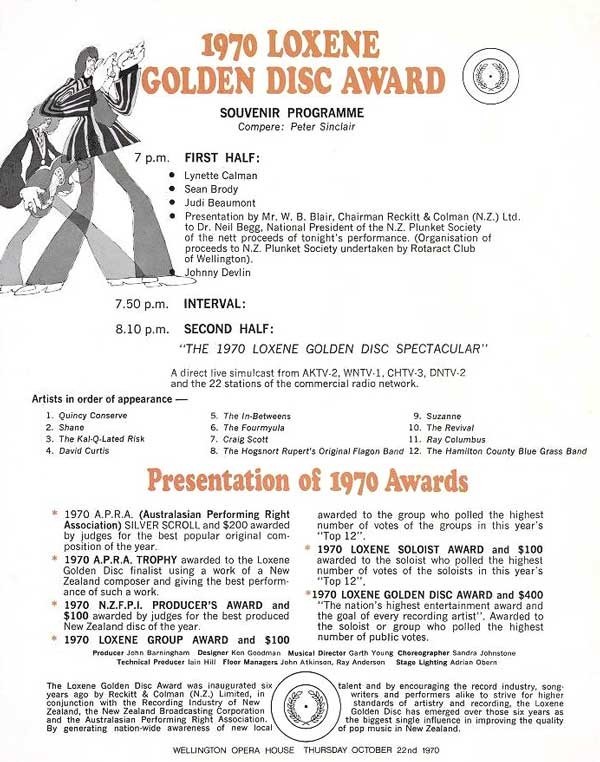

By 1965, the local music industry was thriving and APRA decided to launch the annual Silver Scroll award for the best New Zealand-written song. The first winner was Wayne Kent-Healey for his song ‘Teardrops’, recorded by Herma Keil and The Keil Isles. For the first few years, the Scroll was awarded on the night of the Loxene Golden Disc award, won in that debut year by Ray Columbus and The Invaders for ‘Till We Kissed’. (Columbus won the Scroll the following year for ‘I Need You’.)

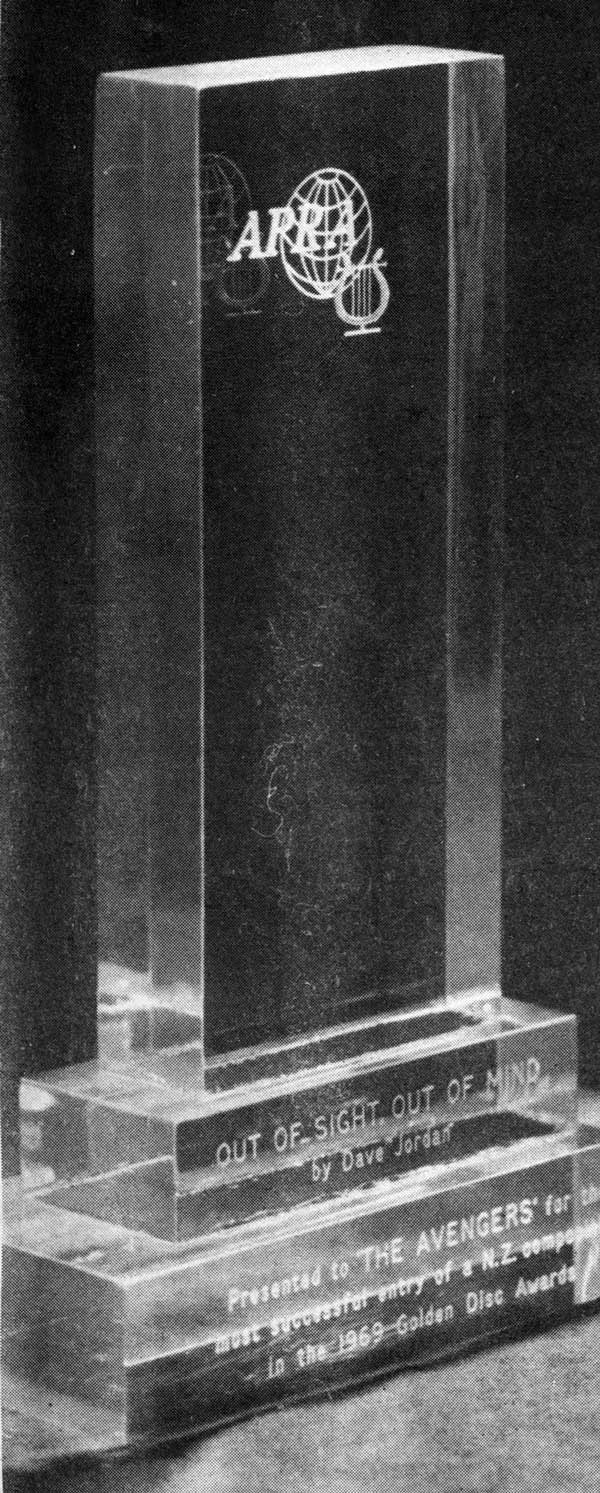

Not the APRA Silver Scroll but the APRA Trophy, which in the Loxene Gold Disc era was awarded to the Loxene finalist who recorded the best performance of a New Zealand composition. In 1969 it went to The Avengers, for their rendition of Dave Jordan’s ‘Out of Sight Out of Mind’.

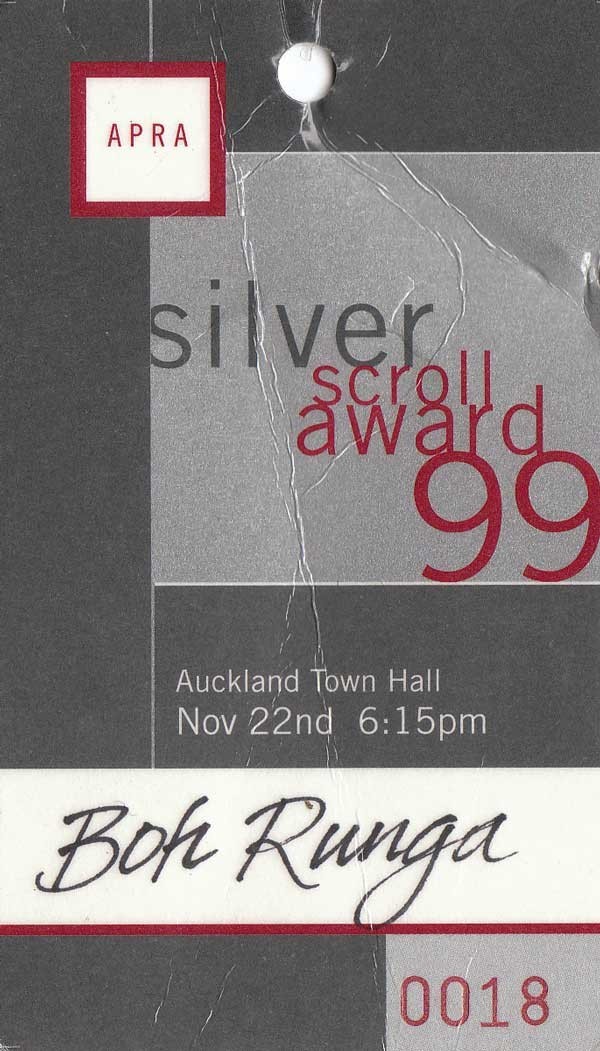

As well as the hefty Silver Scroll trophy – a much more impressive ornament than the annual record awards have ever produced – Kent-Healey won £100. In the following years, respected names such as Roger Skinner, Ray Columbus, Dave Jordan, Wayne Mason and Corben Simpson won the Scroll (Simpson's 1971 Scroll-winner 'Have You Heard a Man Cry?' was awarded an APRA Golden Scroll in 1975 for the best New Zealand composition of the previous 10 years). Male dominance has been challenged by winners such as Lea Maalfrid, Sharon O’Neill, Shona Laing and Bic Runga (Maalfrid and Laing have both won twice).

The 1970 Loxene Golden Disc and APRA Silver Scroll programme

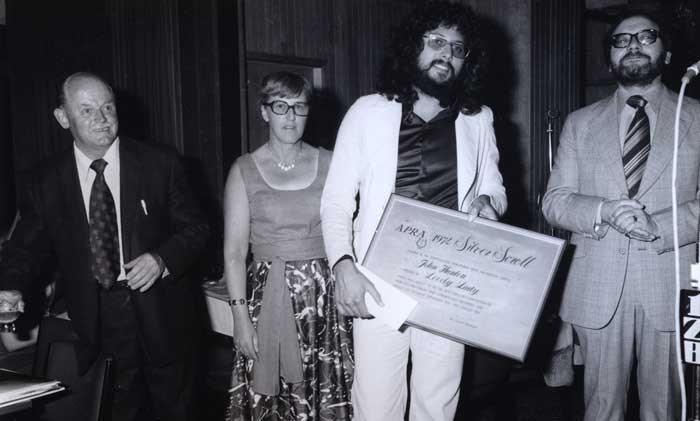

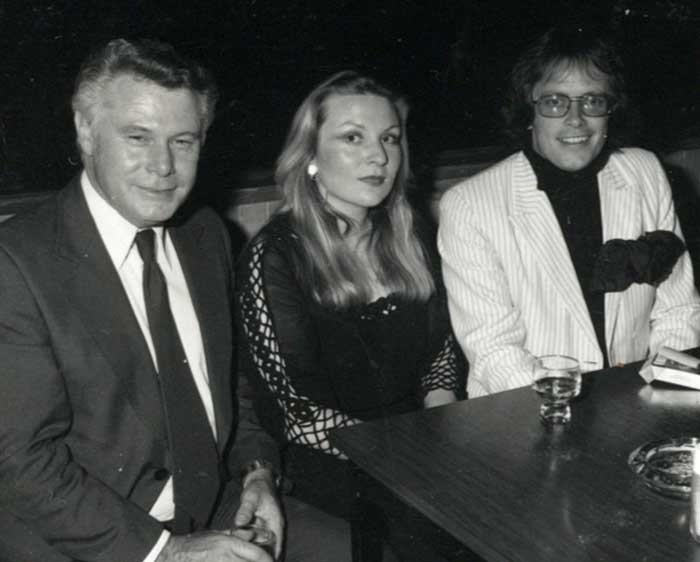

The APRA Silver Scroll awards in 1974 with Wally Ransom, Pat Bell, often regarded as the founder of the APRA Silver Scrolls, winner John Hanlon and UK bandleader and conductor Ron Goodwin

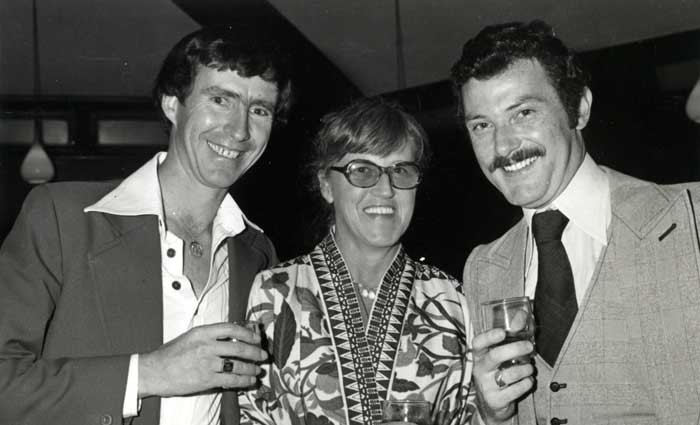

John Sturman (head of APRA Australia), Lea Maalfrid and Ray Columbus at the Tamaki Yacht Club in the mid-1970s

APRA's John Wallace and Pat Bell with Murray McLaughlan, 1976

Inevitably in a competition, plenty of contenders miss out and the unexpected often happens. In 1982 Graham Brazier’s ‘Billy Bold’ lost to ‘I Can’t Sing Very Well’ by Stephen Young of Mother Goose. Dave Dobbyn’s ‘Loyal’ missed out to Laing’s ‘Soviet Snow’ in 1988, but he has won three times; Neil Finn did not win until 2001, with one of his lesser-known songs, ‘Turn And Run’. Perhaps the most conspicuous names to be missing are Jordan Luck (The Exponents) and Martin Phillipps (The Chills). ‘Submarine Bells’ by Phillipps was a runner-up in 1990, when Guy Wishart’s ‘Don’t Take Me For Granted’ won.

The writers themselves have to enter, which is why Luck had no luck with his early classics, and why in New Zealand Neil Finn wasn’t a finalist until 1993 with ‘Distant Sun’ from Crowded House’s Together Alone.

Mike Chunn, the manager of APRA NZ for 11 years from 1992, explained recently: “In the late 70s and early 80s – if not through to the 90s – major artists didn’t enter.” The Scrolls were a much more low-key event, held in a nightclub or restaurant, and aimed at “middle-of-the-road socialising”, says Chunn. “I used to go. I was running Mushroom Records. Did my artist DD Smash enter? I don’t think they did.” Although all the “top-shelf” writers were members of APRA, many didn’t take part. “My brother Geoffrey never entered; Neil and Tim never entered; Jordan Luck didn’t enter as a Dance Exponent writer.

“In Australia hit songs won APRA awards as they weren’t entered by the writer but acknowledged by an APRA-appointed panel. Just like what has happened here in regard to the 1981 group.”

In 1981, there was a new manager at APRA NZ, Bernie Darby, a genial solicitor who had spent many years at Broadcasting, where handling copyright was one of his roles. Other changes taking place that year also worked against the Silver Scroll being held. Composer and arranger Bernie Allen was on the New Zealand APRA music committee that year, and later on the Composers’ Foundation, which was under the auspices of APRA. Responding to a query from Simon Grigg, he said, “Looking through my notes of meetings … I believe that the handover of responsibilities for APRA grants was being transferred from one to the other. The APRA committee had been disbanded and the formalities of the set-up of the NZCF had not been finalised. It was likely that no money was available for such awards as the Silver Scroll in the set-up period.”

But even if the event had been held, many of the finalists in the “lost scroll” would not have entered. The Silver Scroll just didn’t have the prominence it developed under Chunn, whose successor Ant Healey has taken the event to even greater heights. When Darby joined in 1980, he had intended to lift APRA’s profile in New Zealand – however he came from the copyright business rather than show business. And he quickly found that the “serious” composers knew how to assert their mana, and champion ideas they felt APRA should support.

1976: Ray Columbus, Bob Hughes (Australian Writer Director on the APRA board), Max Cryer and Pat Bell

The stalwart of the Silver Scroll since its inception was Bert Rolfe’s assistant, Pat Bell, who joined APRA NZ in the 1950s. When she died in 2000, Heenan recalled her “ebullient nature”, and her rapport with pioneering composers such as Lilburn, Llewellyn Jones, Vernon Griffiths and others. “Very efficient she was too. She never seemed to lose her jolly nature and she had a sharp, retentive mind.”

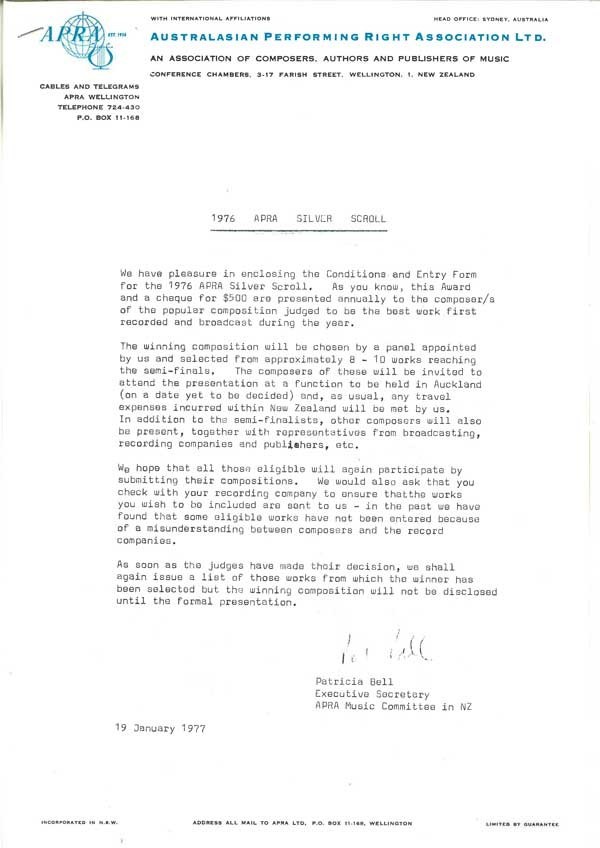

The letter sent out with the entry form in 1977

When Rolfe retired, he was succeeded by Don McKinnon (not the MP), and when he was transferred to Australia, Bell effectively managed APRA NZ until the appointment of Darby. “The pop composers owe Pat quite a bit,” wrote Heenan, “as when the Loxene Gold Competition [sic] discontinued and it looked like the Silver Scroll was doomed, she played no small part in retaining the Silver Scroll on its own. It was held annually at the Tamaki Boat Club in Auckland and Pat attended to all the invitations and publicity, persuading composers to attend this function which was highly successful.” She even made sure some “serious” composers – who were notorious serious drinkers – got home safely by taxi afterwards.

When Bell was succeeded by Darby, says Heenan, “although she did not quite agree with some of Bernie’s ideas about the Silver Scroll function, she very loyally went along with them and became an indispensable part of his team.”

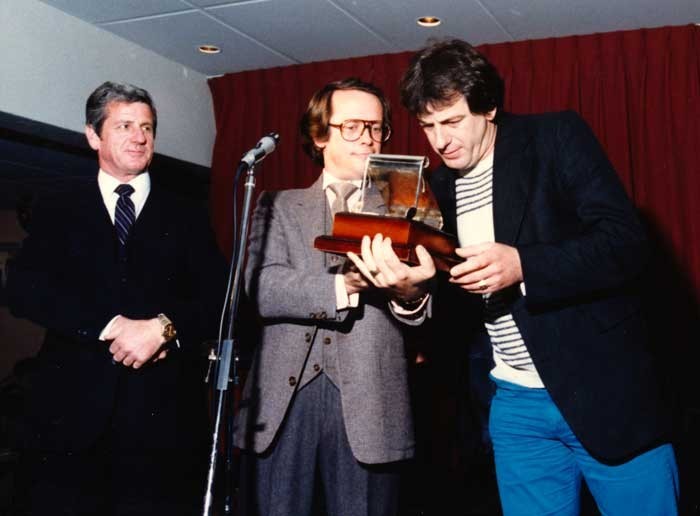

Bernie Darby and Ray Columbus with Hammond Gamble, who had just won the 1984 Silver Scroll for 'Look What Midnight's Done To Me'

The photos of the Silver Scroll functions from the 1970s and 1980s show that they were small-scale evenings, attended by a few industry legends such as Eldred Stebbing and Benny Levin, and only a few songwriters: usually the finalists and previous winners.

The 1990 nominees with the the Silver Scroll winner that year, Guy Wishart for 'Don't Take Me For Granted'

Longtime APRA member, songwriter, film composer, jingle writer and raconteur Jim Hall, recently described it as a “very stratified organisation in 1981 run by Dickensian characters based in Wellington.” He quips it was “dedicated to maintaining the status quo and keeping out the riff-raff. The annual AGM was a catch-up opp for old school academics and MOR specialists. The Silver Scroll was a small part of the evening, a concession to puerile ‘pop’ music. The rest of the evening was about proper music, whatever the hell that was. When APRA moved to Auckland the Mike Chunn era began; it was a major seismic event and the end of the old guard. APRA went from being an exclusive fiefdom to becoming almost too easy to join – but it was waaaay better!”

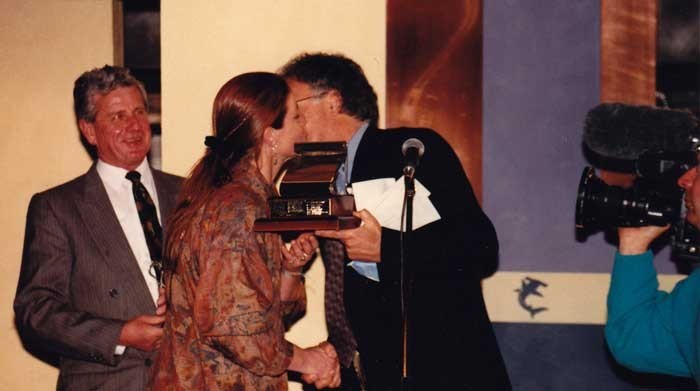

Bernie Darby and Mike Perjanik award Shona Laing with the 1992 Silver Scroll for 'Mercy Of Love'

Maree Sheehan performing in 1995

Bic Runga receiving the 1996 Silver Scroll from Anthony Ioasa and Paul Casserly for 'Drive'

Hall recalls a “gruelling application process” to join in the early 1980s, and compares it to the exclusivity of the original American collection agency ASCAP. In the first half of the 20th Century, ASCAP represented “serious” composers and “serious” pop songwriters such as George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin and Harold Arlen. But genres such as country and black music were shut out. So when the film studios started buying up the music publishers – and demanding a higher royalty from radio stations – the stations formed their own collection agency, Broadcast Music Inc (BMI). The result was more country and black music got airplay, which led to the arrival and dominance of rock’n’roll. (For decades, most country, rock and black writers were represented in the US by BMI, Neil Finn among them.)

The Feelers' manager Tim Groenendaal, Mushroom Music's Jackie Dennis and Paul Holmes

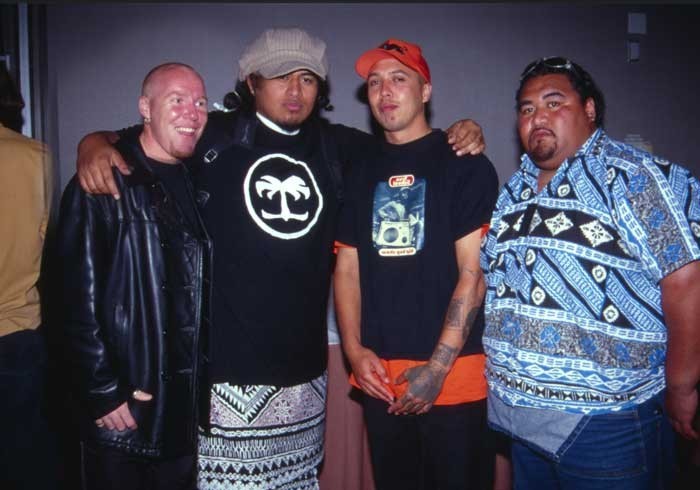

Matty J Ruys, Johnni Sagala, Darry "DLT' Thompson and Danny "Brother D" Leaosavai'i, 1999

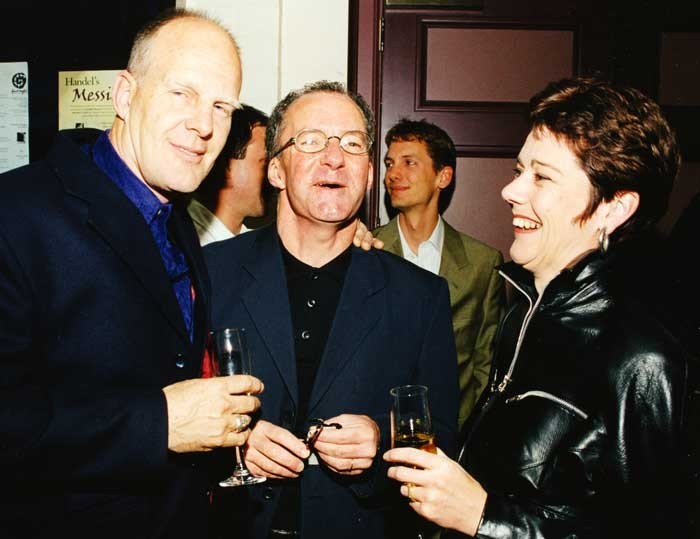

Fane Flaws, Brendan Smyth and NZ on Air CEO Jo Tyndall, 1999

Ironically – after years in which Lilburn and Heenan are the dominant figures in APRA photos, resplendent in tuxedos – in the 1990s, New Zealand’s contemporary composers felt they should also be acknowledged on the night of the Silver Scroll. After overtures by composers, the Sounz Contemporary Award was established. Other genres, which seemed to miss out due to the dominance of mainstream pop, were included when awards for Māori, country, and children’s songwriting were established (the latter two are presented at separate events).

Ruia Aperahama with the 2004 Maioha award for 'E Tae'

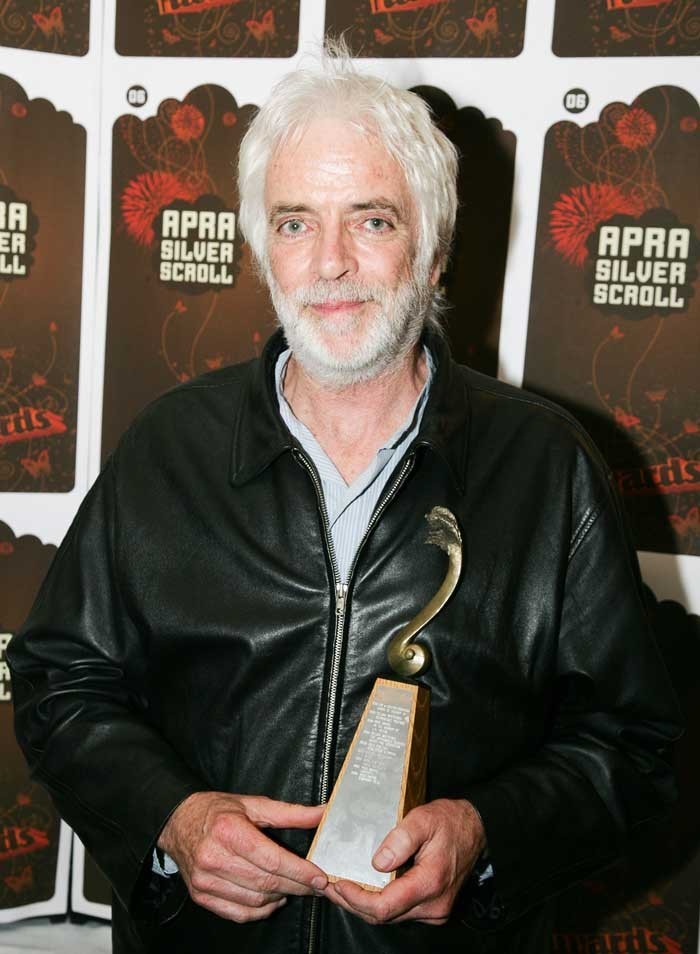

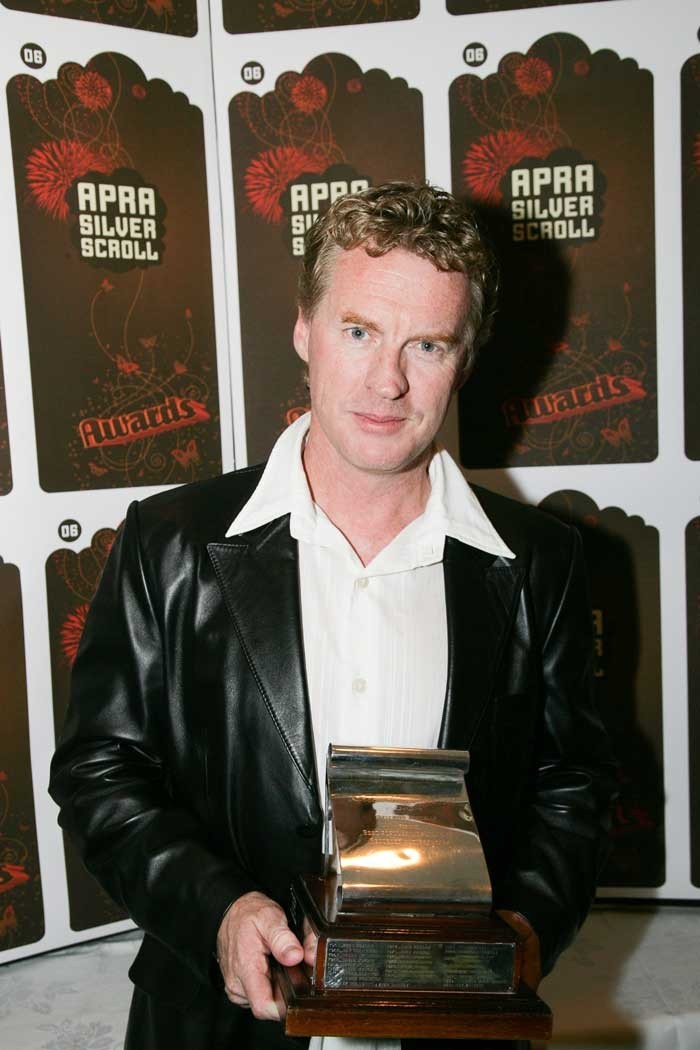

Ross Harris with the 2006 Sounz Contemporary Award for 'Symphony No.2'

What makes a song a Silver Scroll winner? Godfrey de Grut – winner in 2002 for Che Fu's ‘Misty Frequencies’ – wrote: “I’m not entirely sure. Many attributes predicating platinum album sales (probably not applicable anymore), or success on the airwaves, don’t necessarily apply to a winning ‘Scroll’ song. You will always need a great hook with an accessible melody, but stylistically hard metal and drum and bass, though sometimes highly melodic, are unlikely to win the judge’s votes.

“I have found that Silver Scroll winners are invariably ‘nice’ songs. Nostalgia, love and empowerment reign supreme, because these are the universal traits that most people aspire to. As writers we can wrap these subjects in a dark or humorous metaphor, but there is always an underlying positivity that shines through.”

Evermore with the 2005 APRA Silver Scroll for 'It's Too Late'

In the last 20 years there have been some unforgettable Silver Scroll moments. Some big: Martin Phillipps and The Chills closing the 2008 show performing ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’ accompanied by a virtuoso on the massive Auckland Town Hall pipe organ, the Auckland Youth Choir and two rhythmic gymnasts. And some small: the Topp Twins gender-bending Neil Finn’s ‘She Will Have Her Way’ in 1998. In 2009 the event was held in Christchurch for the first time. Emotions were high as Richard Nunns acknowledged the recent passing of Māori songwriter Hirini Melbourne, and James Milne (AKA Lawrence Arabia) – winner of the Scroll with Luke Buda (The Phoenix Foundation) for ‘Apple Pie Bed’ – gave a shout out to Chris Knox after his stroke. He dedicated his award to Knox, “someone who can songwrite us all under the table and a great hero of mine.”

Dylan Taite interviews Chris Knox, the 2000 Silver Scroll winner for 'My Only Friend'

Knox – though a member of APRA since the heyday of Toy Love in 1980 – was originally disinclined to participate in the award. He won in 2000 for ‘My Only Friend’, and the following year attended only his third Scroll: the lavish event held for the 75th anniversary of APRA. To mark the occasion, a special prize was awarded to the best New Zealand song written in the previous 75 years, chosen by APRA’s 10,000 members and some invited participants.

Phil Warren comments in the NZ Listener on the 75th Anniversary vote - Courtesy of Nick Bollinger

The 2001 awards were held in a huge venue in an eastern suburb of Auckland. Knox reviewed the night for APRAp, the organisation’s magazine. “Some of us had never actually been to Kohimarama before,” he wrote. Everyone entered through a green silk tunnel “that smacks of dance party” and was presented with a Midori cocktail. Knox found himself seated “two seats from John Tamihere, almost directly opposite Judith Tizard, Christine Fletcher just behind us (all rightly honourable at some stage … some more than others). Where’s the fuckin’ SONGWRITERS?”

Graham Brazier performing at the 2001 ceremony

The event got underway: Julia Deans’ ‘Lydia’ (Fur Patrol) was the most-performed song locally that year, and Neil Finn’s ‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’ continued its hold on the award for international performances. Gillian Whitehead won the Sounz Contemporary award, and Knox wrote: “I cheer and stamp cos the ‘classic’ stuff sounded far raunchier and evil than most of the ‘rocknpopnrap’ stuff.”

It was an intense night, with many on edge – especially the songwriters – as a countdown of the Top 10 songs for the big 75th anniversary award took place. (Eventually the 30 finalists would be released as Nature’s Best, and the massive sales of this compilation changed New Zealanders’ perceptions of the country’s legacy of songwriting). During the night some serious men in moustaches entered, wearing suits with suspicious bulges under the armpits: preparation for a hit-and-run visit by the PM, Helen Clark.

Secrecy was high. “Countdown time,” wrote Knox, “and it ain’t too surprising except Tim Finn wrote about 140 better songs than ‘Leaky Boat’ but this is made up for by the presence of ‘She Speeds’ and a great DD-less rendition of ‘Slice of Heaven’ from Herbs. Things get a little spooky when prime contenders Dobbyn and Finn are relegated to 3 & 2 but Wayne Mason at the next table is starting to look a little agitated and, sure enough, ‘Nature’ is the winner by a nose, and a David Long-enhanced Mutton Birds makes a bloody good fist of it. And we cheer.”

The Mutton Birds perform 'Nature' with Wayne Mason at the APRA 75th celebrations, ASB Stadium Kohimarama, 2001

John Campbell, MC that night, once said to me, “Radio awards mean everything if you win – but nothing if you don’t win.” With any awards, there will be grumbles: about the system, about the judges, about recurrent awards to dominant talents. But there (usually) has to be just one winner, which doesn’t mean the other finalists are less worthy. The great thing about the Silver Scroll is that it is an award about creativity, not sales, and since the early 1990s the judging systems have been sensible. For 10 years it was judged by a panel of interested specialists who were disinterested, conflict-wise, and in the recent decade, it has been the APRA members themselves. With the huge numbers now voting, this may end up becoming like the Oscar, which favours middle-of-the-road entries rather than ground-breakers. But with winners such as ‘Apple Pie Bed’, ‘Bathe in the River’, ‘Not Many’, and last year’s ‘Walk (Back to Your Arms)’, this has not yet occurred.

Don McGlashan with the 2006 APRA Silver Scroll for 'Bathe In the River'

The Silver Scroll event is a celebration rather than a competition. Almost inevitably, ‘Royals’ won in 2013, in the very week that it topped the US charts, and the feeling in the room was as if everyone was a winner. Late that night, news came through that Eleanor Catton’s novel The Luminaries had won the Booker Prize in the UK. Musicians and writers may not be flag-wavers, but the hungover emotion the next day was “now we’re getting somewhere”. In 1970 Arthur Baysting, reporting on New Zealand’s pop year for Australia’s APRA Journal, wrote: “The fact remains that the big money is overseas … So far the only international star has been John Rowles but with the right breaks there should be others following in his footsteps.”

The tyranny of distance conquered, Lorde (Ella Yelich-O’Connor) and Joel Little, writers of ‘Royals’ – and finalists with ‘Yellow Flicker Beat’ – were absent from the 2015 Silver Scroll, held on 15 September. Yelich-O’Connor was mixing with luminaries in New York, Little writing for them in Los Angeles. Held in part of Auckland’s cavernous Vector Arena, the 50th anniversary show was always going to be special. It was certainly epic, in length and scale: an orchestra assembled by musical director Godfrey de Grut as the house band must have numbered 20 musicians.

John Rowles performs 'Cheryl Moana Marie' at the 2011 APRA Silver Scroll awards

Bill Sevesi – steel guitar legend, mentor for generations as bandleader, producer, and advocate of music in schools – was inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame, aged 92. His charm won over everyone present with his aphorisms about the importance of music to life. Jordan Luck paid tribute to Graham Brazier, with special emphasis on his generosity to other musicians, the characters he invented in his lyrics, and his love of language. “Graham once told me, ‘Sing ’til they put you in a pine box – and then come back and haunt them.’ ” Delaney Davidson followed with a sparse, moving rendition of ‘Billy Bold’, the string section providing a stately coda with their segue into ‘Jerusalem’.

Herbs receive the Hall Of Fame Legacy award in 2012

In an evening with much mockery of the flag debate, the opening item was a Māori group dressed in Union Jack togas, sashaying through a medley of the five “lost Scroll” finalists, in te reo (‘There is No Depression’ sounded especially subversive). Don McGlashan’s speech was a lesson in what makes a New Zealand song, deftly accompanying himself as he shrewdly analysed Graeme Downes’ ‘Death And The Maiden’ (on the pause before the “Verlaine, Verlaine” hook: “Graeme’s a South Islander: the punchline is the quietest part of the joke”) and Neil Finn’s ‘Into Temptation’ (“Only a New Zealander would let the sun come out unexpectedly by using a G Major chord on temptation”).

APRA NZ Chief Executive Ant Healey at the 2014 APRA Silver Scroll awards

So songwriting and composing was the focus, not celebrity. ‘Counting the Beat’ was an appropriate winner of the “lost Scroll”, being pop songwriting of geometric perfection. ‘There Is No Depression In New Zealand’ captured the zeitgeist of 1981, but the joy of singing The Swingers’ “La da de da” chorus has not faded one iota in nearly 35 years (and its connection with ‘Nature’ warrants further analysis).

‘Aotearoa’ by Stan Walker, Vince Harder and Troy Kingi won the Maioha Award, and its uplifting rendition by the kapa haka group Ngā Takere Nui o Ngā Waka made it seem like a contender to follow ‘Poi E’ as a No.1 hit in te reo. Chris Watson’s ‘Sing Songs Self’ won the Sounz Contemporary Award, and enjoyed a free-jazz interpretation by Julien and Paul Dyne, and MC John Campbell enticed a delightful story about the song’s title from Watson (it is his son’s expression for singing himself to sleep).

2013 APRA Silver Scroll winners, for 'Royals', Joel Little and Ella Yelich-O’Connor (Lorde) with former APRA NZ Head of Operations Mike Chunn at the 2014 awards with their certificates for the most international airplay, also for 'Royals'

But the main event was the songs we will be singing in the future: ‘Dark Child’ (by Tim Moore and Marlon Williams; recorded by Williams), ‘Multi-Love’ (Ruban and Kody Nielson; Unknown Mortal Orchestra), ‘Get Out Alive’ (Mel Parsons, who also recorded it), ‘Water Underground’ (Anthonie Tonnon, who recorded it), and ‘Yellow Flicker Beat’ (Ella Yelich-O’Connor and Joel Little; Lorde).

After being finalists in several Silver Scrolls, the Nielson brothers took out this year’s trophy for ‘Multi-Love’. Earlier, the hook-filled song had been given a sparse treatment by a vocal trio of Warren Maxwell, Thomas Oliver and Louis Baker. But the prize for novel interpretation must be for Lorde’s ‘Yellow Flicker Beat’ – vocal diva Ria Hall was accompanied by Mark de Clive-Lowe, playing on several keyboards live from a studio in Los Angeles. Shayne Carter swaggered through ‘Counting the Beat’ accompanied by the full Silver Scroll Orchestra, somehow managing humility, delight and deference to the original.

In the video tribute to Bill Sevesi – which featured a rare appearance from singer Daphne Walker – someone mentioned his wish that the ukulele would “bring out the musicality of New Zealanders”. John Campbell described how in his childhood none of the music he heard came from New Zealand, and stressed how the band compilation Class of 81 was “a revelation”. The big-production years of the Silver Scroll have always been about pride among peers, and with recent international success and radio airplay now more regular, what once felt desperate is now just determined. The 2015 event was the celebration of a supportive musical community: it does feel that now we’re getting somewhere.

Scribe (with P-Money) wins the 2004 Silver Scroll for 'Not Many'