Now that was rude. International pop star Robin Gibb, on asking if the audience is “Having a luvly time?” gets pelted with a flying tomato. Then a young man dashes for the stage and is intercepted by the under-resourced police and security detail. Breaking away, one arm still held, he dances a fake foxtrot with his captor, drawing laughter from the large crowd and prompting yet more flying cans and missiles.

Out there in the audience are nine to ten thousand popular music fans who have been shepherded to the site by buses and trains from the central railway station. An estimated 1,500 fans from throughout the country will stay overnight in the Redwood Park campground.

Soon after, a girl dressed in white makes it onstage and grabs Gibb around the neck, pushing him into the music stands behind. She’s quickly followed by a male fan who heads for the microphone before being repelled by a policeman.

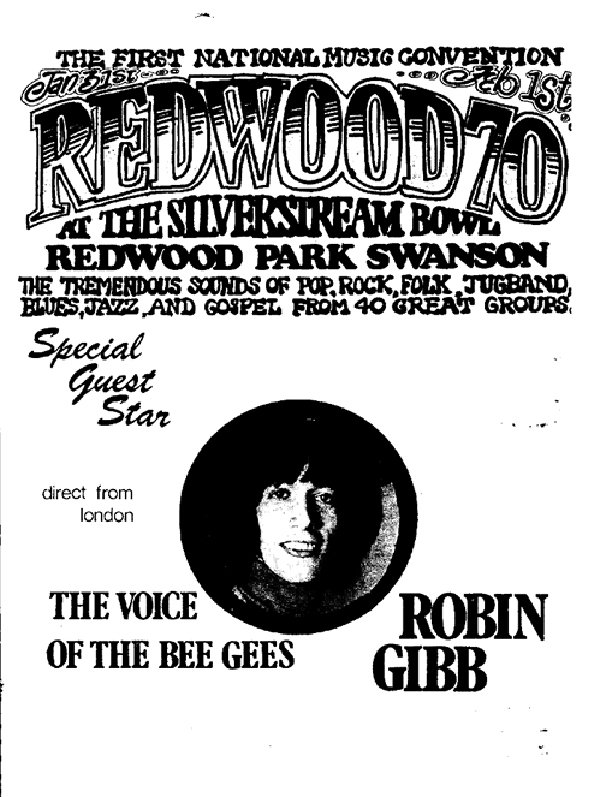

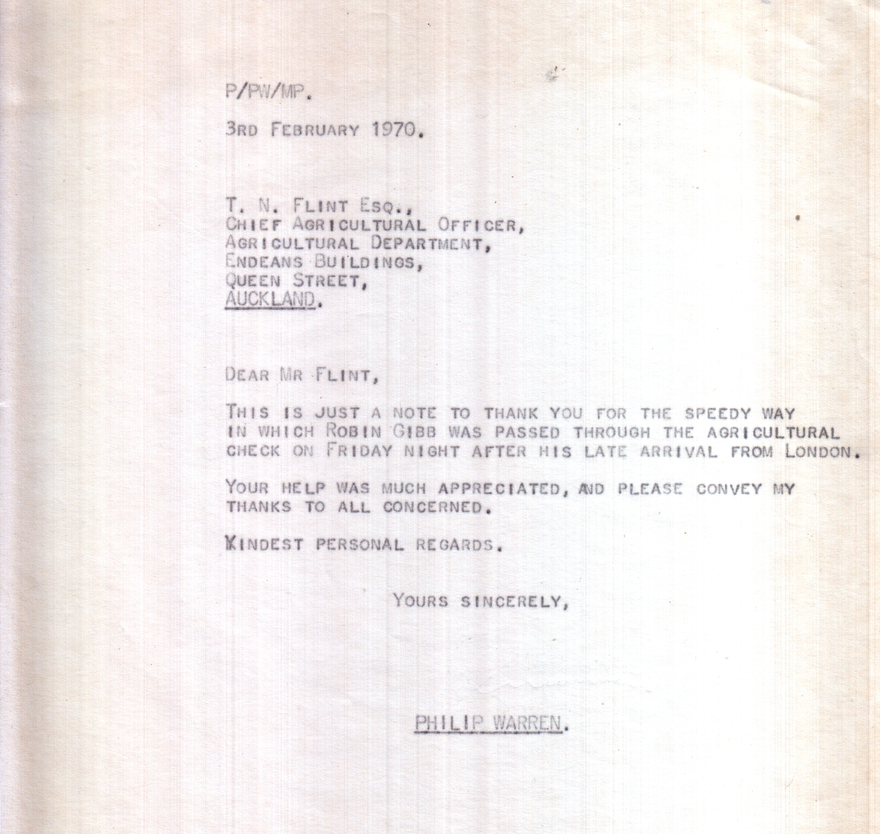

It’s been a rough evening for the solo Bee Gee, who is flying high on the back of ‘Saved By The Bell’, a huge hit single for him in 1969. He touched down at Auckland International Airport a day earlier (January 30, 1970) with manager Ray Washbourne and musical director Kenny Clayton. Now he’s facing a partly adoring, partly disapproving evening crowd in a Swanson park at the foot of West Auckland’s Waitakere Ranges.

Behind him, the 17-piece orchestra brought together by Mr E Bibobi for Gibb’s two Redwood 70 shows are exiting the stage one by one as the missiles rain down, until only the drummer and bass player remain.

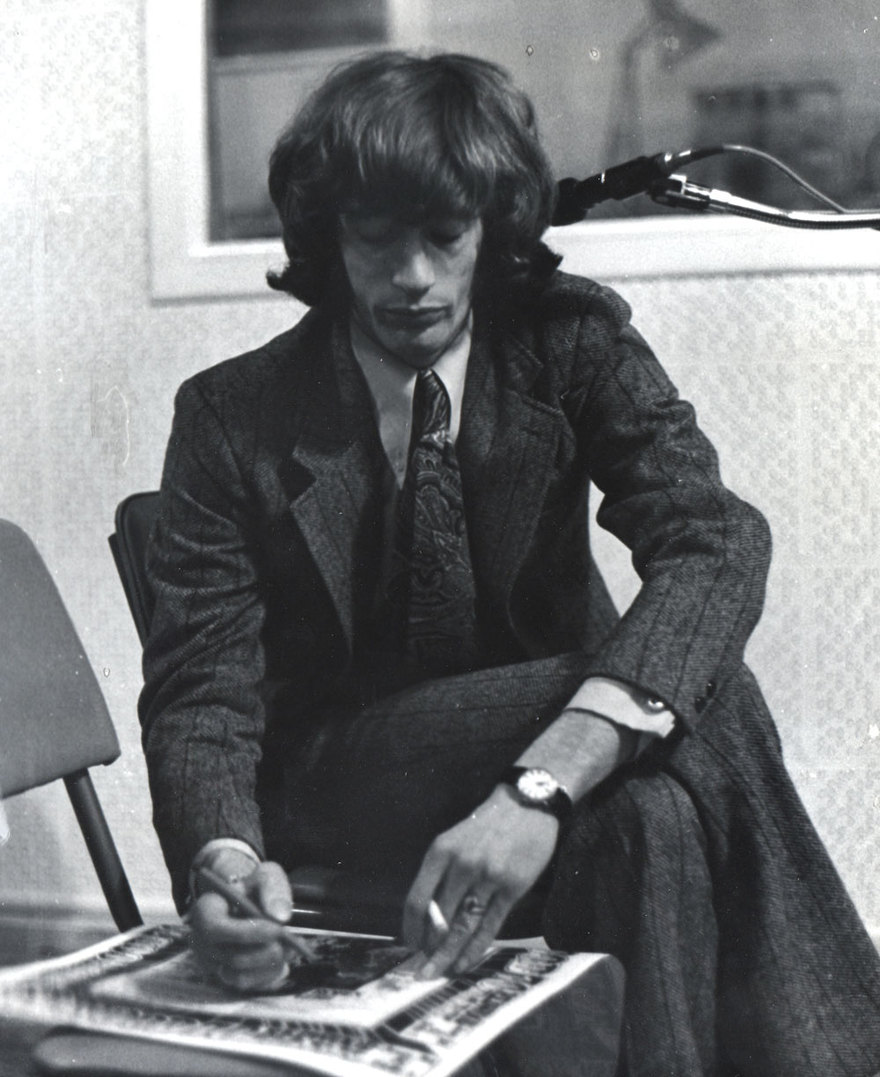

Robin Gibb signing Redwood 70 posters - Photo by Kevin Lane. Phil Warren collection

Robin Gibb – described by the Auckland Star’s Tony Potter as a “slight figure in a brown suit and white turtle neck sweater (who) had no stage act to speak of. No gyrating, awkward bump and grind dancing, just beautiful arresting singing” in a “quavering tenor voice” – finally retreats to safety, his one-hour set cut to 35 minutes.

Writing to the orchestra members in the festival’s wake, promoter Phil Warren tells them, “after the Saturday night performance, we wondered whether we’d have an orchestra at all on the Sunday.”

When Robin Gibb returned for his late Sunday afternoon slot, security was beefed up considerably and the crowd held well back, leaving the previous night’s ruckus as a slim slice of controversy in an otherwise peaceful gathering. Despite illegal fires being lit on Saturday evening and Auckland Star reporting, “in the crowd, ugly scenes continued”, there were only three arrests for minor offences over the two-day event.

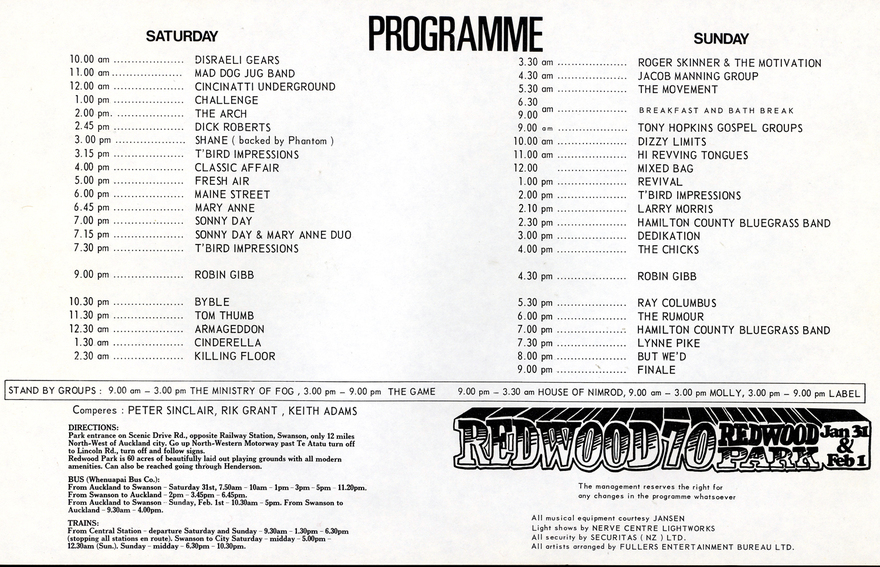

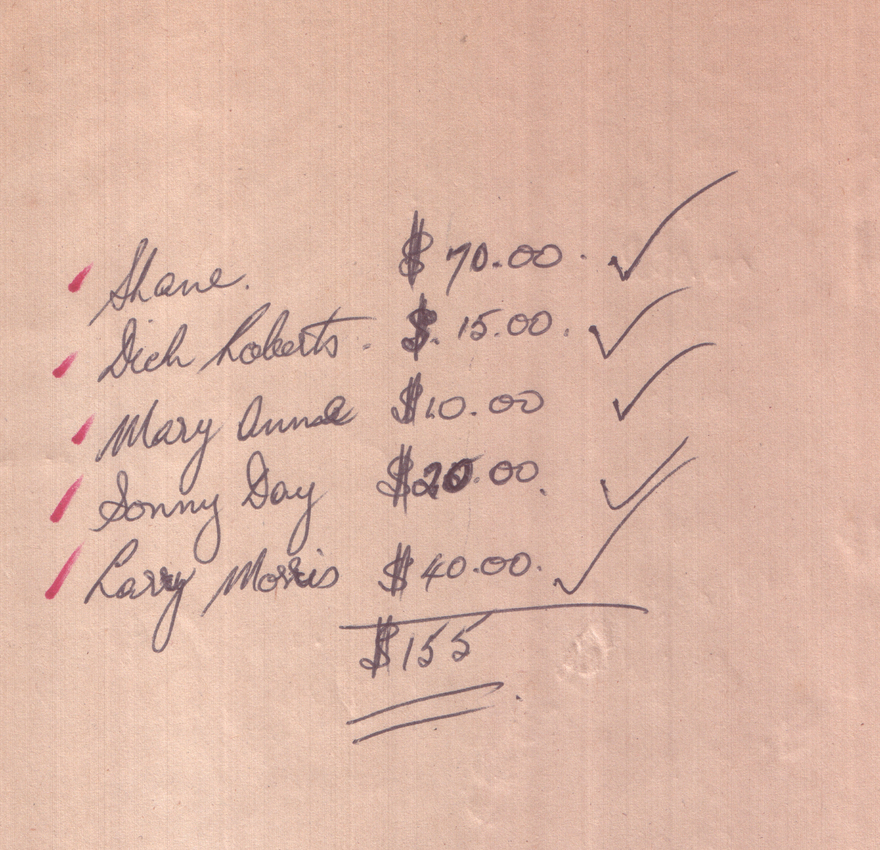

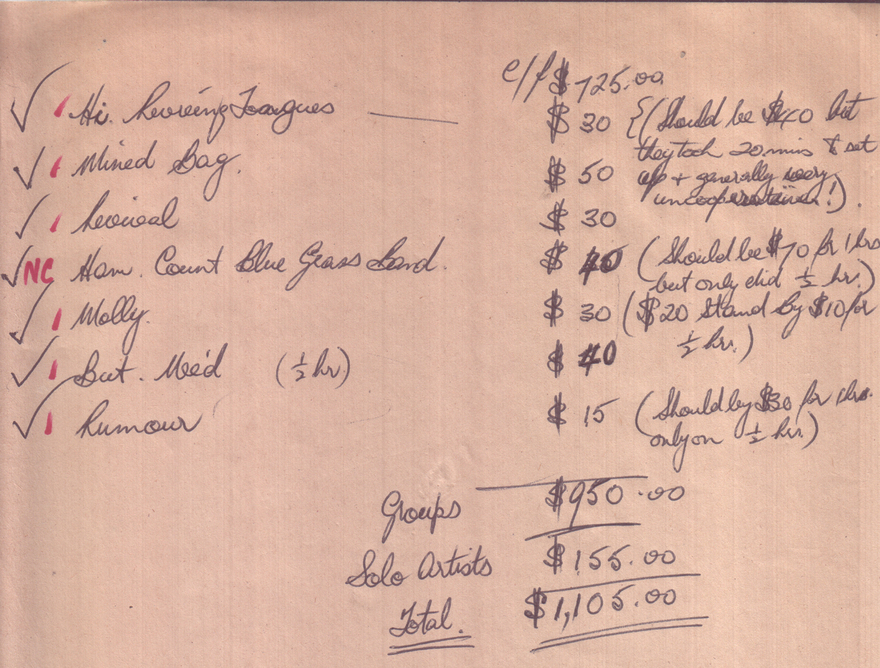

The schedule for Redwood 70. Shane, the highest paid NZ act (Ray Columbus is not listed on the pay schedule and may have gotten more) played for only 15 minutes.

The wider musical content is in contrast barely covered by the mainstream media, who ignore the strong, diverse local bill that promoter Phil Warren’s Prestige Promotions had assembled.

Flagged by some reporters as New Zealand’s Woodstock – the massive generational gathering in upstate New York in August 1969 – Redwood 70 was more likely a version of the Monterey International Pop Music Festival of June 1967. It was organised by old school music industry professionals as a pop take on previously successful jazz and folk festivals and an advancement on the varied pop package tours of the mid to late 1960s. It was staged in an established recreation park as opposed to a green fields site. It has the same catholic mix of sound, from folk and ethnic through soulful solo singers, to acts influenced by the blues-rock of Hendrix, Cream and Led Zeppelin.

The Chicks

But where Monterey signalled what was to come, Redwood 70 evidenced the already established divide between pop and the increasingly politicised and musically diverse underground. For every popular soloist (Ray Columbus, Larry Morris, Troubled Mind’s Dick Roberts, Shane with Bruce “Phantom” Robinson, and Sonny Day), for every hit pop act (The Chicks, Hi-Revving Tongues, Classic Affair, The Rumour and The Challenge) and jazz, country folk and gospel choir (Fresh Air, Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, Mad Dog Jug Band, Killing Floor and Tony Hopkins’ Gospel Groups), there is a psych-blues and proto-hard rock combo, drawn mostly from the Auckland, Wellington and Hamilton club scenes.

Shane

The first day concluded with The Byble (built around the core of The Smoke) and Wellington’s Tom Thumb onstage, followed by Hamilton’s Armageddon. That’s right, the bible, smoke, the apocalypse, and a group whose most famous song was a rocked up version of ‘If I Was A Carpenter’.

Wellington provided Dedikation and The Dizzy Limits, while Hamilton turned out Cinderella, The Jacob Manning Group and The Movement in the early hours of Sunday morning.

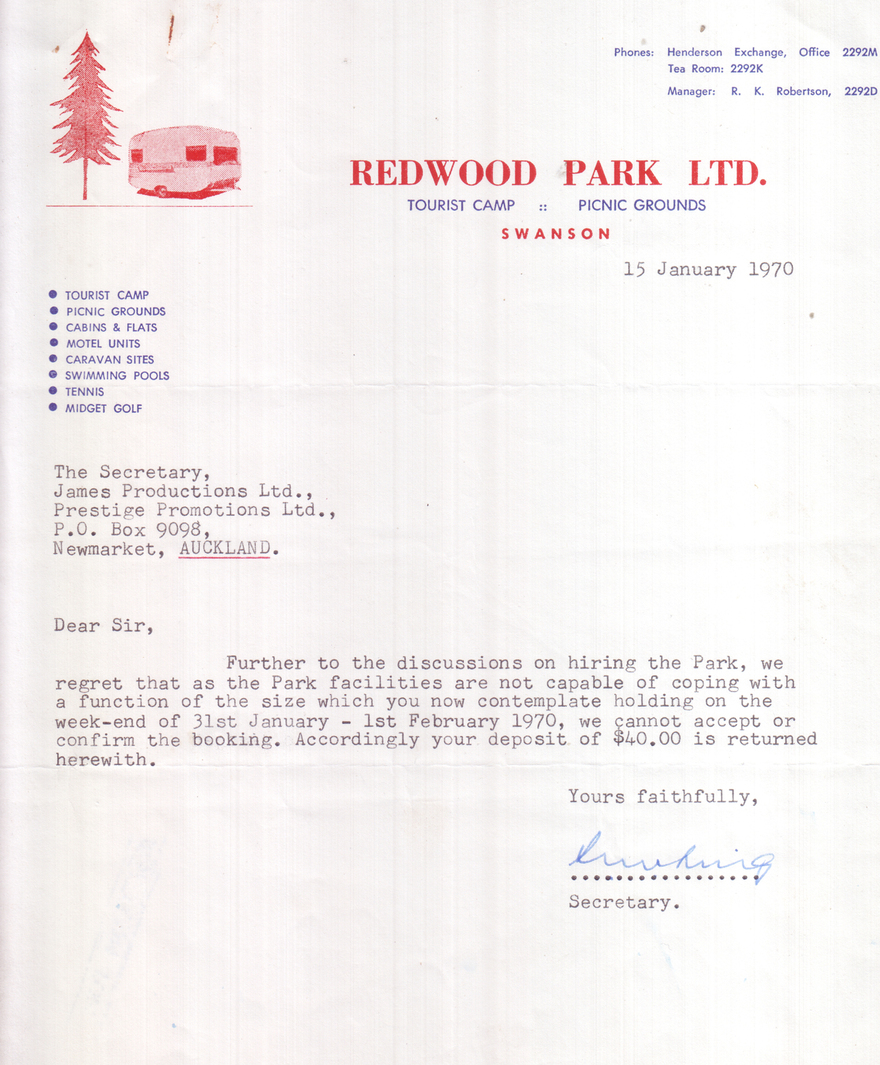

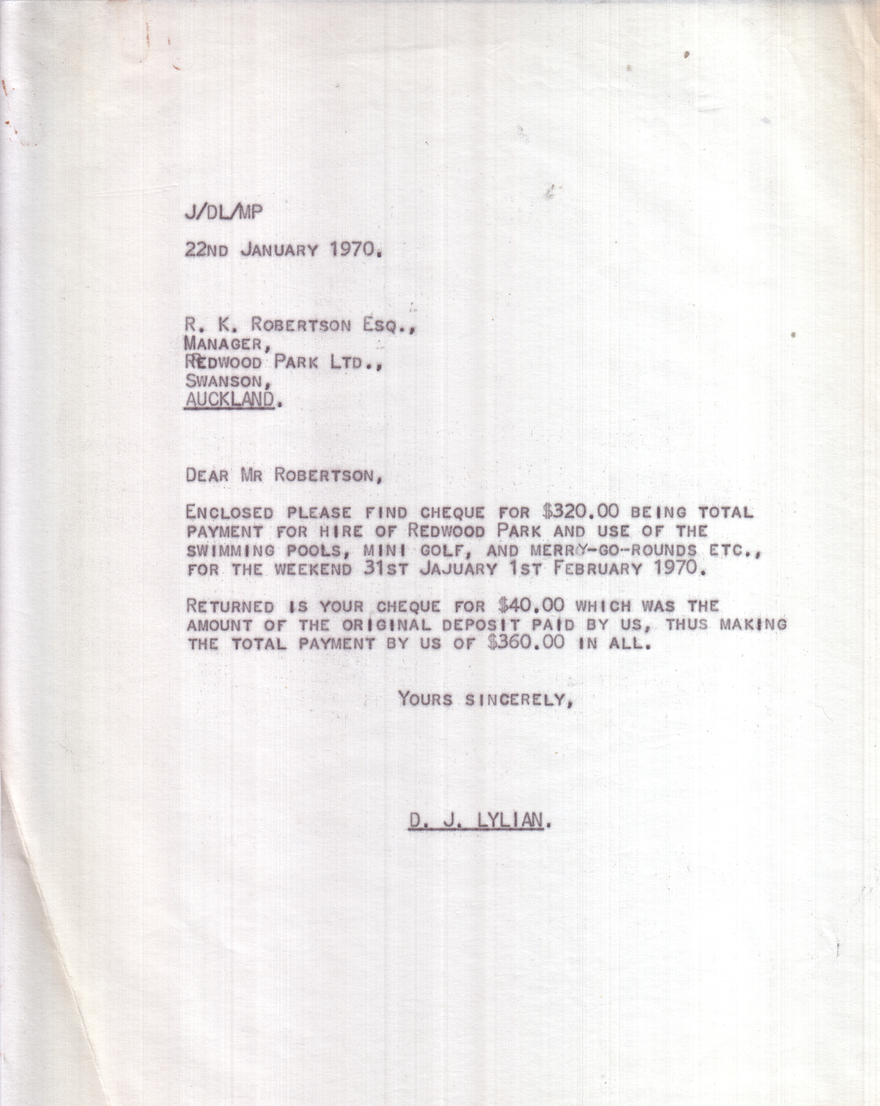

In mid-January, two weeks before the festival, Redwood Park declined the booking and returned the deposit.

They were joined on the bill by groups who were resident at one of the many clubs in Auckland, including The Forum in Takapuna, the Tabla, a cellar club in Lorne Street, The Bowl, and Aubrey’s in inner city Auckland. For some bands, such as Disraeli Gears and Hi-Revving Tongues, this would be their last performance. For others, including Paul Hewson’s The Arch and stand-by groups The Ministry of Fog and House of Nimrod (who did make it on stage), and The Cincinnati Underground, there was a way to go yet.

Seven days later the booking was confirmed by Don Lylian, Phil Warren's business partner. What went on between the 15th and the 22nd is unclear.

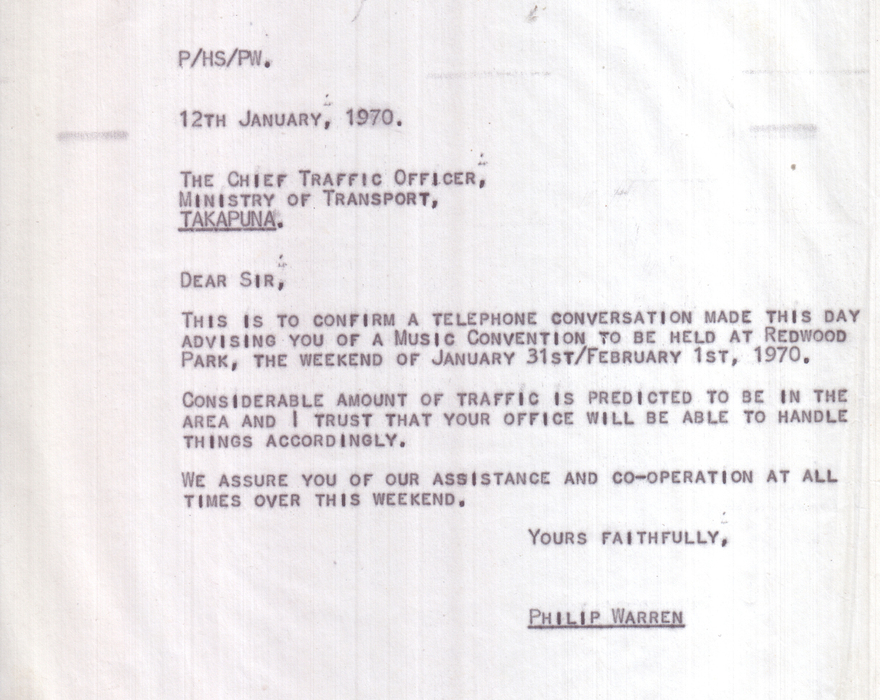

However we do know that three days before the 15th of January, and the returned deposit, Phil Warren told the traffic department of the MOT the event was confirmed.

The Cincinnati Underground’s singer Les Richards recalls. “We played the two day festival at Redwood Park with some of us backing Robin Gibb. We played at the festival three times – we were that much in demand. We were also televised for a documentary – it was two minutes of me sliding around the stage doing a Jim Morrison and a few backing tracks over which people were interviewed.”

Among their songs that day was a version of The MC5’s ‘Kick Out The Jams’, which the group had recorded in 1969 with three other covers at Astor studios in a session paid for by Max Cryer.

Among their songs that day was a version of The MC5’s ‘Kick Out The Jams’, which the group had recorded in 1969 with three other covers at Astor studios in a session paid for by Max Cryer.

Despite what the programme said, it was Larry Killip’s Omnibus who kicked off the festival on Saturday morning, having been delayed half an hour because the food stalls were using up too much of the available electricity. That left the onstage sound wanting, a problem soon fixed. The stage was being run by James Productions with MCs Peter Sinclair, Radio Hauraki’s Rik Grant and Keith Adams as the onstage announcers. The sound system was assembled by Roly Magness using Jansen equipment.

In another of his many post-show thank you letters, Phil Warren rated the PA highly. “There is no doubt in any of our minds now that Jansen can stand up with the world’s best equipment,” he said.

One of the few New Zealand acts noted by mainstream media was Fresh Air’s early Saturday evening slot, featuring a 50-minute improvisation, which was “cut short” to the crowd’s displeasure. For the most part Fresh Air were Wellingtonians resident in Auckland, where their jazz inspired “freewheeling, lyrical improvisations” of Chaz Burke-Kennedy and George Barris compositions and obscure album tracks could be heard at the Tabla and at free Albert Park concerts. They were also filmed for an (unscreened) documentary on the underground scene.

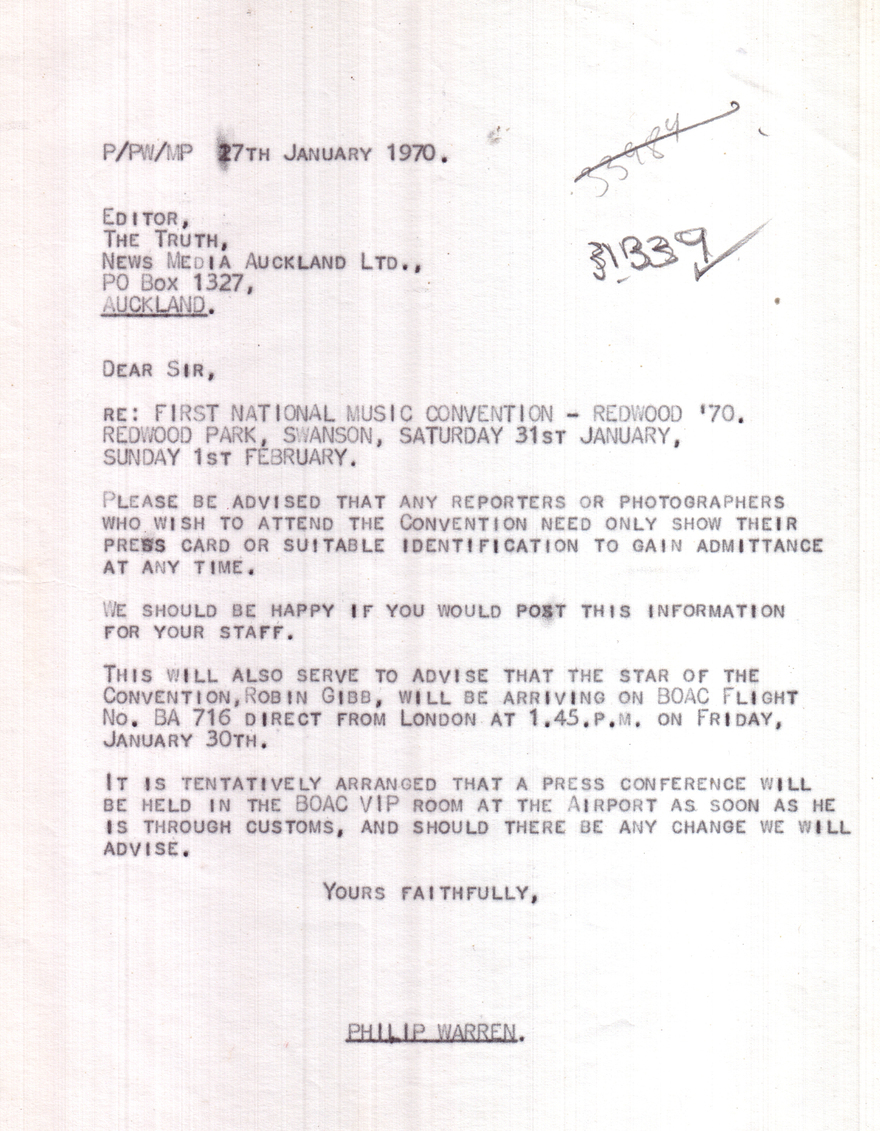

Phil Warren left no possible media outlet untapped. Free tickets were available to the daily newspapers, suburban newspapers, Waikato Times, Sunday News, 8 O’Clock, Sunday Times, Truth, Playdate, teen magazine Eve, NZ Women’s Weekly (who always covered pop music well), Thursday magazine, Radio Hauraki, NZBC and Radio I.

Where money changed hands, as with Radio I, coverage demands were made. Warren expected station reporters to be at Gibb’s airport arrival. The festival’s headliner would/should be supported by strong playlisting of songs by Gibb and The Bee Gees. Up to date information on transport to the site was to be provided and the Radio I spotter plane was asked to make several sweeps of the site. A “rave” about Saturday’s proceedings was also expected.

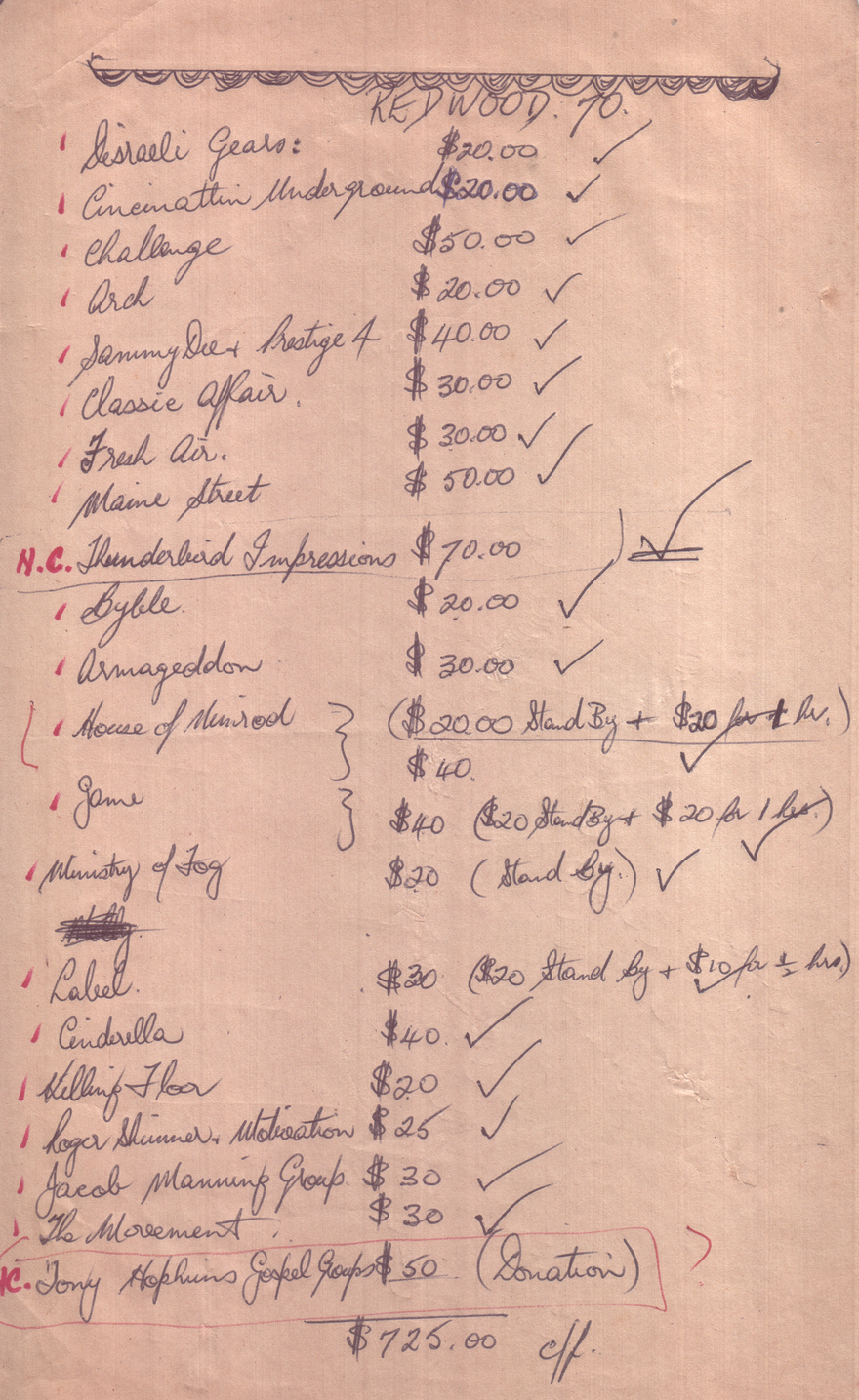

The veteran promoter was keeping an eagle eye on the festival acts as well. Hi-Revving Tongues, who despite having a massive hit with the soaring ballad ‘Rain and Tears’ in 1969, were both louder and more rock and roll live, were docked $10 off their $40 fee for “taking 20 minutes to set up and being generally very un-co-operative". Hamilton County Bluegrass Band lost nearly half their $75 fee for playing only half an hour, as did The Rumour.

Page 1 of the original pay schedule for Redwood - Shane was clearly a bigger star than most.

Another page of fees for Redwood - of interest is the fact that Thunderbird Impressions got the same fee as the local music star Shane, although for that money they played three times, presumably doing impressions.

The final page of the payment schedule for Redwood. The Hi-Revving Tongues are noted as "should be $40 but they took 20 mins to set up + generally very uncooperative", while Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, Molly, and The Rumour were all docked for only doing half a set each.

The Redwood 70 National Music Convention finished four hours early, at 6pm on Sunday, February 1, following police advice that the park be cleared before dark. Phil Warren didn’t make back his $25,000 costs, but on a cultural level he and his crew had succeeded.

Despite what looked to be slim lead-in times in the organization of the event, the festival ran smoothly. There was no community discord before or during Redwood 70. Government and local body organizations were well informed and compliant. The media mucked in.

Forty of these media invitations were sent out, to every news or gossip outlet that mattered. Phil Warren was very, very, thorough when it came to covering all angles. The media came to the party and there was extensive coverage.

Covering all angles included several dozen thank-you letters, including this one to the 1970 equivalent of MAF.

There was just that last minute letter dated January 15 from the Redwood Park campground manager trying to cancel the event, which by then had become too overwhelming for him. Phil Warren’s reply to this crisis is nowhere to found in his records. Regardless, Redwood 70 was New Zealand’s first major multi-day pop festival.