Phil Warren was a young entrepreneur who made sixties New Zealand swing. He had a finger in every pie – at 17 he ran a record label, while still a teenager he recorded rock and roll legend Johnny Devlin, and he ran a talent agency, venues, promoted concert tours and owned clubs. As a high-profile club owner, Warren had to his fight for the right to party when New Zealand’s old prohibition-style liquor laws outlawed alcohol in clubs.

This is an expanded version of Murray Cammick’s interview with Phil Warren that first appeared in Real Groove magazine, November 2000.

Phil Warren got started in the music business afterschool as a 14 year old mail boy at Charles Begg’s record store, Queen St, Auckland. Warren soon decided that playing music was not for him.

“I was a very bad musician. I learnt very early in life that I was a terrible musician and I felt that I could assist musicians and entertainers rather than be a musician and that was when I really got involved in records.”

After leaving school Warren worked with Charlie Western, a musical instrument distributor (Yamaha pianos), where he made his first foray into selling records, the Clef jazz label (now Verve). After six months Charlie decided there was more money in musical instruments and at 18, in 1956, Philip Warren Ltd was founded.

“I chased all the independent overseas labels that HMV didn’t have tied up. I got them from all over the world and really made an impact on the market – Roulette, Warner Bros, Verve, Oriole etc. I dealt not only with the Mafia out of New York but the black Mafia out of Chicago. They were good to deal with.”

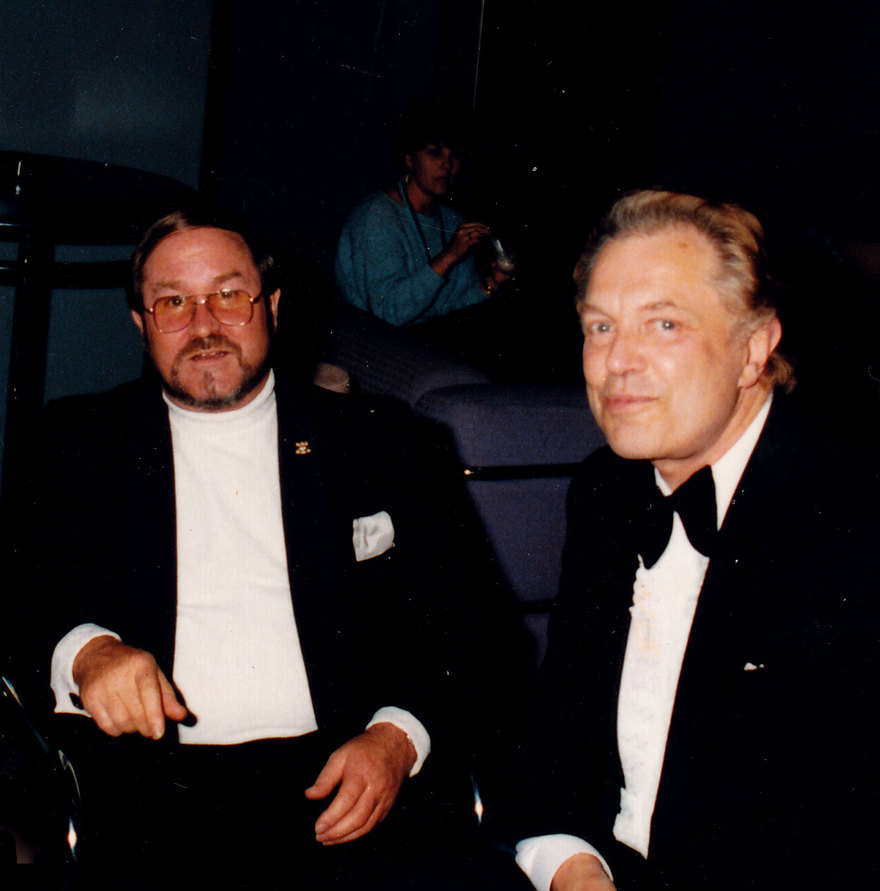

Two key players in the New Zealand music industry for several decades, Phil Warren with Pye and WEA Records boss Tim Murdoch in 1976

Did the HMV retail monopoly take your releases?

“Initially they didn’t, except some of their record store managers, who were trying to do the correct and proper job for the public they served, did take my stuff. They got a rap over the hands from head office.

“Columbus Radio Shops stocked our records, they were selling radiograms and they couldn’t sell HMV records, because HMV wouldn’t give anybody the records.”

Columbus Radio Shops had to start their own label, TANZA (To Assist NZ Artists). What was big for you?

“Warner Bros were very small when you think of Time Warner today! They’d just started off, one of their best selling records was Spike Jones Dinner Music.”

“If I could say one record put me over the hump so I’d never have to worry again, it was Salad Days, a stage show from England that was performed here by the New Zealand Players with Richard Campion (Jane Campion’s father). After 10,000 imports of the London production we started to press here.”

“Foreign 45s, we smash released them – we dubbed them here.”

“Then we looked at the local acts too — Johnny Devlin, Carol Davies, Vince Callaher, Kahu Pineaha. We sold lots and lots of records by these people. And also at that time I’d leapt into the promotion of the dance halls. It was a combination of things happening with the synergies bouncing off each other.”

Signing Johnny Devlin in 1958, mania soon swept the country and the following year his ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ sold tens of thousands of records, although Warren admits his 100,000 sales figure was exaggerated.

Could Harry M. Miller and yourself be equally accused of making up sales figures?

“I think so. Harry Miller was here a couple of years. He was too big for New Zealand. Harry wanted to be a big fish in big pond. I was quite happy to be a big fish in a little pond.”

Phil Warren with entertainer Max Cryer in 1990

Was Johnny Devlin a special talent or just the right man at the right time?

“Yes, he was the right man at the right place at the right time but if he didn’t have the talent he couldn’t have delivered and got the following that he got. It’s never happened again, even with the power of television and Mr. Lee Grant, it never happened as big as Devlin.

Was he New Zealand’s Elvis?

“I think every country had one. Cliff Richard was England’s Elvis. Johnny O’Keefe was Australia’s Elvis. Everybody had an Elvis, even the French [Johnny Hallyday]. Devlin was our Elvis.”

Devlin’s shirts were made with teen hysteria in mind.

“The Devlin shirts were sewn together so they fell apart when they were pulled. They fell apart on the first tug. But he had a great figure he didn’t mind showing off. It’s called show business.”

When Phil Warren started doing business with an Australia-based American, Lee Gordon, Johnny Devlin recordings were released in Australia (and Devlin went to live there) and Warren became an agent for Gordon’s foreign tours.

“I linked up with a man called Lee Gordon in Sydney, an American out of Detroit. He’d immigrated to Australia and found they weren’t doing any music. He started to bring out entertainers from America playing them in the most primitive places. There was a Sydney Stadium that was a tin shed. He also started to do what I was doing here with local artists. He had the Johnny O’Keefe, I had the Johnny Devlin, he had the Col Joye, I had the Vince Callaher. We struck a deal, I would do all his records here and he’d do my records over there. He had his label Leedon (Lee Gordon). Any of the shows he brought to Australia he would offer to me, that’s how I then started to also be doing shows.”

“The first of the big shows that I did here was in 1959 — Johnny Cash, Tommy Sands, the Platters — five or six superstar names all on one package, not like it is now.”

“There was the great rub-off with that. We were able to put our own local acts on the show. We recorded them and toured them and put them in our nightclubs and coffee lounges. There was a magical synergy.

“I still see Johnny Devlin regularly. We didn’t record that many songs with John before he went off to Australia and his records were released by Lee Gordon. And over there it became the battle of Johnny O’Keefe versus Johnny Devlin and they even ran ads with boxing gloves as they promoted the two of them.”

But was the 60s boom in New Zealand music artificial when so many releases were cover versions?

“One instance of that is infamous. Chubby Checker’s ‘The Twist’ was banned by the NZBS (NZ Broadcasting Service) – they didn’t buy it. So I re-recorded it with Herma Keil and The Keil Isles and they didn’t ban that. They took that. Why, I will never know but that made Herma’s version of ‘The Twist’ the big one in New Zealand rather than Chubby Checker.”

In 1960 Phil Warren embarked on a 50/50 partnership with movie theatre tycoon Robert Kerridge and the UK Rank Organisation, founding the Top Rank (later Allied International) record company that after six months, also absorbed Warren’s Prestige label. But Warren only stayed there two years as his other business interests, venues, touring and talent booking were booming.

“Bob Kerridge wanted to get into the record business as the Rank people who were his partners wanted to get into the record business. I discussed it with my partner in Prestige, Bruce Henderson – his family owned the Henderson’s Electrical shop in Newmarket.

“I joined Kerridge on a 50/50 deal. I went off to London – I was about 18 – and met all these people and came back with a swag of material and that was the start of the Top Rank Allied International Record Company. We hadn’t been going for six months and the Phillip Warren Ltd/Prestige company was not doing as well as it could and Bruce Henderson came knocking and I bought the company back and folded it into the Rank Company which was “Allied International Records”.

“Kerridge was always putting great pressure on me because I was not beholden to the company. I had a theatrical agency going that I managed and I booked all the acts and I had dancehalls and coffee lounges all over the country and I had 50% of the company. He didn’t have 100%.”

“I said that I wasn’t happy and it might be better if we parted good friends. He didn’t volunteer to buy the company but he said if you can find a buyer I won’t step in your way and I walked down the road and said to George Wooller, ‘Have I got a deal for you. Your people like these labels I’ve got’. Fred Noad was running the Wooller Group. He jumped at that and we did a deal. That was the end of my relationship with Kerridge.”

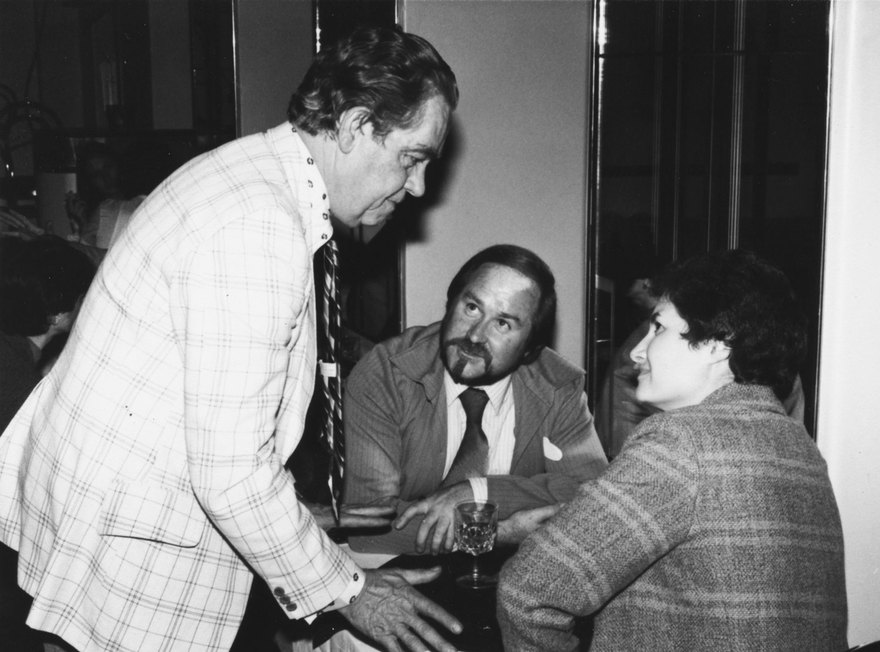

Phil Warren with The Fan Club's Paul Moss (left) and Paul Ellis (then head of A&R at Sony Music, later a TV face and publicist)

Warren sold his half of the company to George Wooller Ltd and ended a whirlwind five years in the record company business. Warren’s 1960s dancehalls and coffee lounges included such cool names as Montmartre (Auckland), Monaco (Auckland), Mojo’s (Auckland), Teenarama (Wellington), The Place (Wellington), Starlight Ballroom (Hamilton) and Aubrey’s (Christchurch). The timely Beatle Inn in Little Queen St starred locals Merseymen with TV rock god Dylan Taite on drums. He was then known as Jett Rink.

“Dylan Taite was a very good drummer and he sung quite well in harmony.”

Did you control local music TV in the 60s, with your Fullers Entertainment Agency exclusively booking all the acts?

“No. It’d be nice. Wouldn’t it be nice! No, you were dealing with a State Organisation, the NZ Broadcasting Corporation. They moved Let’s Go up to Auckland because the bulk of the entertainers were in Auckland. Pete Sinclair and the bright-eyed producer boy Kevan Moore from Wellington sniffed around and ended up on my doorstep and said we want to do these music shows, you seem to have most of the talent tied up, He talked to other people about it but I was the only person who grasped what he was talking about and I made it very easy and said, ‘Yes! We’ll help you in any way we can.’ ”

“We auditioned with Kevan Moore talent that was on our books and talent we advertised for and that was how we virtually were the packagers. All the talent that went on those shows we looked after them.”

You never had a record label again?

“I still had a record production company with Jimmy Sloggett, the musical director for C’mon. We set up a production company James Productions Ltd. If you look at the small print, the C’mon records and the Chicks records are produced by James Productions.”

Did challenging the liquor laws give you as a venue owner an outlaw status?

“We tested the licensing laws to the brink. To show how silly the liquor laws were we pressed them to the limit. I lobbied at the Labour Party and National Party conferences to extend the licensing laws. We ran the Crypt in Auckland as a private club with liquor in a cabinet and as a key club. You paid a subscription to become a member and you got a key that let you into the club or to open the liquor cabinet that you were designated.”

Like a gym locker room?

“Yeah. It worked. It was one way in which we tested the law and then we were taken to court, convicted and fined. George Vanderloo fronted it for me. He took all the flack. He took all the fines. I paid all the fines.”

My perception was that the media were not on your side.

“The media is never on your side. The media only have three things they are interested in, to sell: a victim, a villain or a hero. You’re either one of those. I’ve been all three at various times.”

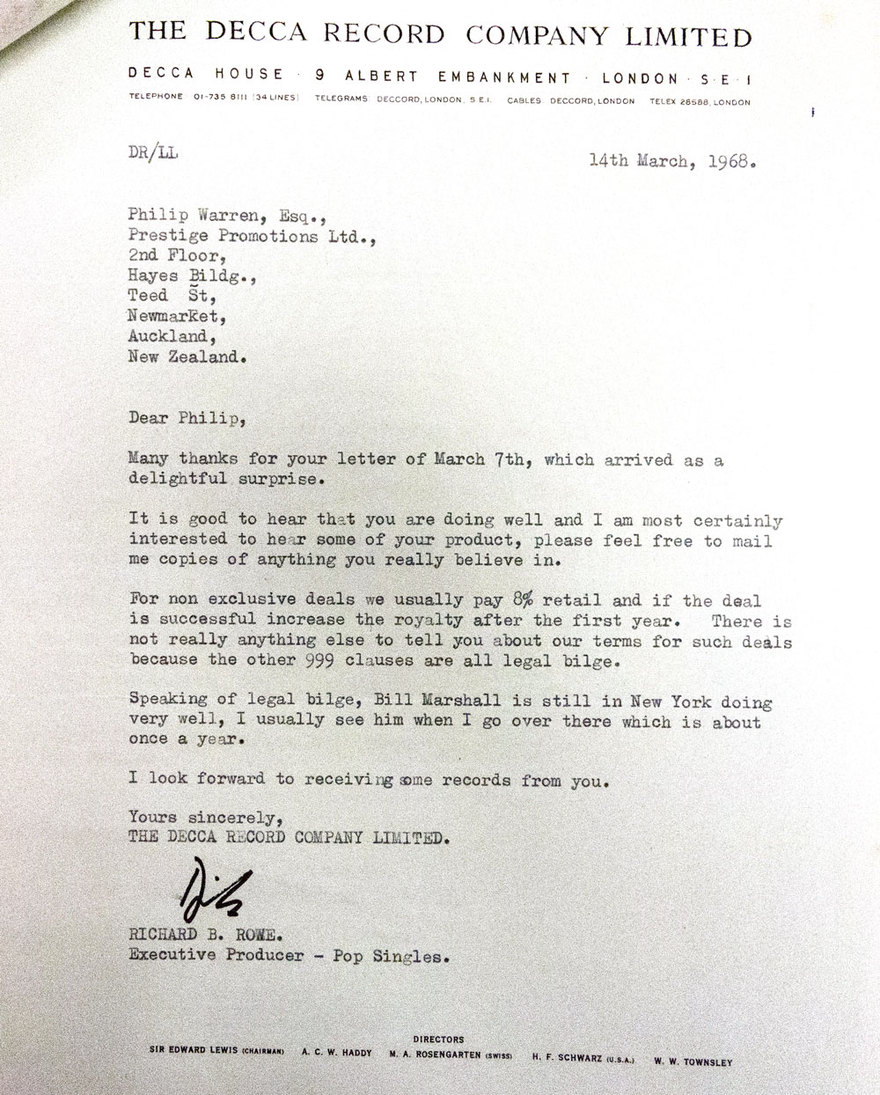

Dick Rowe - the man who "turned down The Beatles" - writes back to Phil Warren, 1968 - Phil Warren collection

A person in the entertainment business was depicted as a villain in the 60s and 70s?

“Yes.”

But journalists wanted to go out and have a drink, wouldn’t they be sympathetic?

“They had their own private drinking clubs.”

They were hypocrites, maybe?

“Maybe, maybe. They certainly never complained when the more liberal liquor laws came about. It was a Godsend to the country. Civilization.”

Did your run-ins with the law ever endanger your entering political office?

“No, because I made bloody sure they didn’t. I was very, very careful with just how far we went and what we did!”

Was there a turning point when prohibition attitudes changed?

“We lived with the prohibition of everything. We knew no better. Unless you travelled overseas you had no idea of what a restricted society we lived in.”

“I tell my kids, to buy a copy of Billboard magazine I had to apply to the bank to get overseas funds. You couldn’t get a new car unless you had overseas funds. They didn’t bother to ask you how you got the overseas funds.”

“One of the advantages in my business when I started was I could not by law, pay any advance royalties! I had Roulette Records, Warner Bros, Oriole Records, all for nothing. If they liked me, they did a deal and there was no advance money. There was no advance royalties because the Government prohibited that. It was a Godsend to me, that helped me make a bloody fortune in the record business.”

“We had our ups and downs. Everybody says I’ve made a fortune, sure I made a fortune but I also lost a fortune. The quickest way to make another fortune is to lose a fortune. You don’t make the same mistakes twice. It was very rewarding for me but it was very rewarding for the people I was working with. They all became superstars.”

The mid-70s were shaky for Phil Warren. Did you retreat from touring, as shows moved to Western Springs?

“No. I got out of touring for a while when I had five shows on the road and who would have thought five shows would go splat together. I didn’t want it to pull everything down. I had to put Prestige Promotions into voluntary liquidation otherwise it would have affected the dancehalls, the clubs, the cabarets and I was working very hard to get “Radio I” away, so the promotion company had to go to the wall.

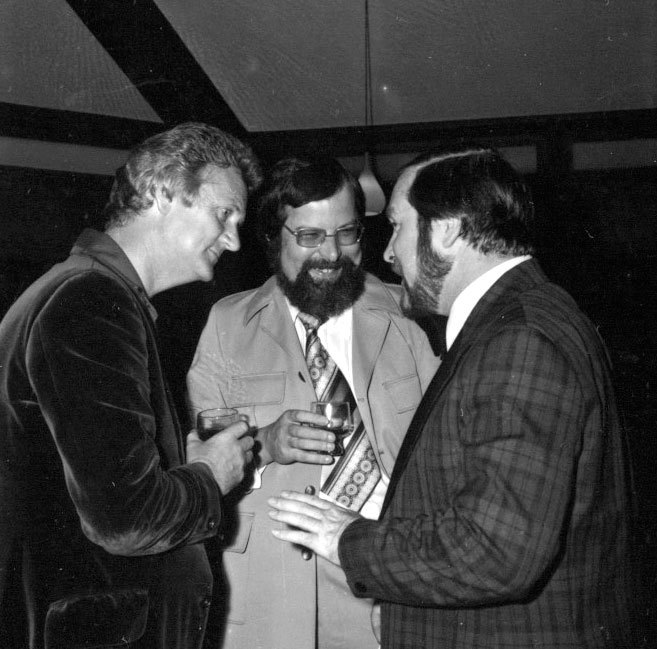

Phil Warren (right) with musician, songwriter and arranger Bernie Allen (centre), 1976. Phil was famous for his stories and seems to be in full flow here.

What were the five shows that went bad at once?

“Barbara Windsor in Carry On Barbara, The Black & White Minstrel Show, Patrick Cargill in Father Dear Father, Tony Christie and one-hit-wonder Daniel Boone.”

Was it tough to make money on stage shows?

“They went on longer. The biggest moneymaker I had here was Gaslight with Pat Phoenix the star of Coronation St. We did about six months. I could have run it for six years. A great stage play.”

Was there a lot of trouble at Paul Dainty’s [Australian promoter] 1974 Faces concert at Western Springs?

“They wanted a big Steinway piano and they got a Yamaha baby grand and they bloody wrecked it. They wrecked the piano from my house. I got an apology from Rod Stewart. He didn’t wreck the piano it was the band. They destroyed it on stage in front of me. There was nothing I could do about it, but I sent them the bill. Dainty agreed with me that they had to pay, so we deducted money and I bought myself a new piano.

Rod Stewart has since refused to tour with Dainty as on that tour he was paid hall fees for big outdoor gigs.

“That’s the old Hollies story with me. Two hours before their Western Springs concert they came to me and said, ‘We didn’t think we’d be playing big outdoor shows. We gave you a concert hall price’. I said, ‘It doesn’t say anything about that in the contract’ and they said, ‘You’d better rethink it or otherwise we’re not going to perform.’ I had to rethink it! We came to a compromise and they were happy.”

The seventies was a decade with good ties and dodgy club names. In 1975 when Phil Warren went into a 50/50 partnership with Lion Breweries the land was graced with the Ace Of Clubs, Dirty Dick’s, Roman Scandals, Bimbos, Slack Alice, Adam’s Apple, the Silver Spade and Doodles.

“I named all our clubs, except Dirty Dick’s, it was running in Australia, too.”

Phil Warren’s most public role was as the tough judge on 1970s TV talent shows such as Studio One / New Faces.

“They only wanted me if I’d play the bad guy. Somebody had to be the bad guy, but I don’t think I was destructive in any criticism. Everything that I said was constructive. People lead people along and unnecessarily build up their hopes and don’t tell them the truth. If I didn’t like Lurex I’d say ‘I don’t like Lurex you shouldn’t have worn that for me’ or ‘Fancy coming on with your shoes looking like that, this isn’t a black and white show, you’re in colour’. Those sorts of comments always got me rubbished in the Monday morning papers throughout the country. I was seen as the baddie. I did those shows for about 10 years and it was a sad day for the industry when those shows stopped.”

Did concert promotion become less profitable?

“In my day I bought an act and paid the act. If the act bombed I lost the money. The act got their money. If the act was a riotous success I kept all the money. But the lawyers and the accountants got into the music business and you have to pay percentages, minimum guarantees and half the time you’re giving 90 percent of everything you take back to the act. I am very grateful that I am not in the business today because that’s not the way to make a lot of money.”

“I think lawyers and accountants are squeezing the goose that lays the golden egg. They’re squeezing the breath out of it. There has to be some incentive for the promoter to do it. I don’t think it’s a great secret how Paul Dainty was hurt [lost millions] by the Rolling Stones tour fiasco and that’s a shame. That’s criminal, it really was, it never should have happened. But Paul being the great entrepreneur that he is, he’s found another partner and he’s come up smiling. In the old days we used to say if you can’t make money on a 50 percent house, you don’t do it. I have a lot of admiration for the young promoters of today who take the risks that are involved nowadays which are totally different from 30 years ago.”

“The 60s, you’re talking about the very best time in the New Zealand music business — they were the halcyon years, the good times. I just happened to be very fortunate to be part of them.”

Recording pioneer and Zodiac label owner Eldred Stebbing with Phil Warren and Bev Wakem (now Dame Beverley Wakem, former Chief Ombudsman), then CEO Radio New Zealand, 1982.

Do we lack entrepreneurs in music today?

“There’s no get-up and go. We had to get out and hustle. You didn’t expect people to give you things or get things for nothing. I don’t say that just about the entrepreneurs, I say that about the musicians and artists too, they worked their arses off to move a record.”

“We’re a pimple on the arse of the world. We’re 3 and a half million people. We’re a suburb of London. If we want our musicians to make money, they have to do their apprenticeship here and then go off overseas and make the big bucks. We’re three and a half million people. When they have made all the big bucks that they want they can come back here and conduct their business affairs from here, have the best of both worlds, living here and touring overseas.”

“If you think you’re going to be a millionaire in the music industry living in New Zealand. Forget it! We don’t have the critical mass. We don’t have the people. If you want to be bigger, you have to bugger off.”