As if the city’s musical culture was pausing for breath before a mighty plunge, the Christchurch City Libraries' Christchurch Music Timeline has no entry at all for 1980.

The plunge came early the next year, when Roger Shepherd launched Flying Nun Records, New Zealand’s most famous indie label – and, although it would relocate north seven years later, the enduring icon of Christchurch’s musical history.

Flying Nun did not come from the void: there were things happening in 1980, and in the years before.

But Flying Nun did not come from the void: there were things happening in 1980, and in the years before. Since the early 1960s, Max Merritt and The Meteors, Ray Columbus and The Invaders, Dinah Lee and the blazing Chants R&B had all emerged in the Garden City. Like The Beatles in Liverpool, they were all greatly influenced by access to American R&B Records – in their case, via the jukebox at the Operation Deep Freeze base out at the airport.

But it could be that the road to 1981 began in 1975, which saw, among other things, the arrival of another overseas influence: a genial Englishman called Olly Scott. Scott was the son of a Bletchley Park World War II code-breaker who surfaced in Christchurch and started teaching the kids around him songs they didn't hear on the radio – the Stooges and other kinds of punk before there was punk. If there was a musical template for the following generation of Christchurch bands, Olly Scott drew some of the first lines on it.

He became the centre of a band called the Detroit Hemroids – later the Basket Cases – whose members would go on to Toy Love, The Gordons, The Androidss, Bailter Space, The Playthings, The Bats and others.

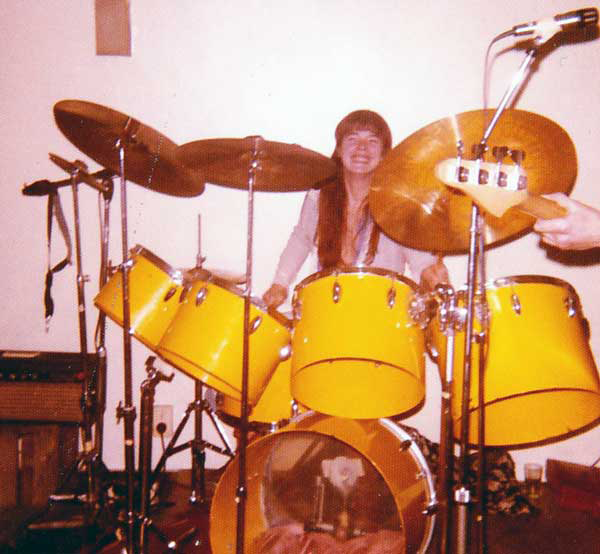

Jane Walker, Paul Kean and Alister Parker in The Basket Cases at The Gresham – photo by Ian Dalziel

Roy Montgomery also remembers the middle of the decade as a time when the “happy hippie” period began to turn into something stranger, telling The Big City in 2012:

“Things got weirder as the decade wore on. I remember sitting in the Christchurch Town Hall in what I thought I was a pretty adventurous pinstripe suit from an op shop waiting for Lou Reed to come in the mid-70s, when he was touring Rock and Roll Animal, and looking behind me to see several people dressed so outrageously that it made Lou Reed look like an accountant when he finally took the stage. I distinctly remember one Māori gentleman who was dressed in a Hussar’s uniform with an Afro and white make-up. Not long after that I found The Gladstone and the denizens there who seemed bent on carrying on the tradition of Andy Warhol’s Factory irrespective of the bands who played the three-nighters.”

Jane Walker in The Basket Cases at The Gresham–photo by Ian Dalziel

The Factory aesthetic must have seemed a good fit for the Christchurch underground. This was the scene, memorably described by Andrew Schmidt as a “patchwork crowd of young punks, counterculture survivors and Garden City oddballs”, that formed the audience at the city's first punk rock club (or at least the first place that allowed punk rock bands to play), Mollett Street market, in 1977 and 1978. Mollett Street was first opened as a venue by Al Park, later of The Vandals. Park would go on to book The Gladstone after Mollett Street closed.

In a nice illustration of the strange juxtaposition of the weird and bohemian and the unabashedly commercial that has often characterised the city’s musical culture, at the same time as the weirdos were gathering at Mollett Street, most of the recordings for Christchurch’s “other” famous record label, Hoghton Hughes’ Music World, were being knocked out by nameless session bands at John Phair’s Tandem Studios, barely a hundred metres away on Colombo. In 1978, at the peak of punk, Music World released an album called Golden Saxophones. It went on to sell well over half a million copies.

Tony Peake - photo by Mike L. Williams

By then, another influential outsider, Tony Peake, an Australian who, like Scott, had come to live in Christchurch in 1975, was making his presence felt musically (and was shortly invited by Al Park to join his punk band, The Vandals). Although they were quite different people – Scott the oddball English rocker, Peake the cool sophisticate – both men were generous with their time and both had great taste.

These bohemian crowds also converged at The Gresham, a Cashel Street pub that hosted bands and was also a centre for the city’s gay community.

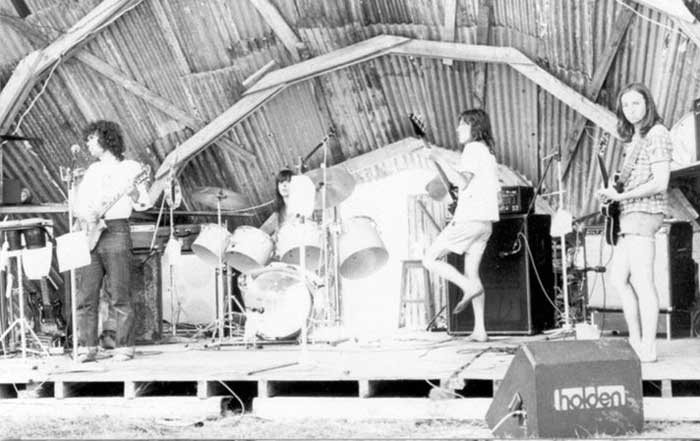

The Detroit Hemroids at Punakaiki on the West Coast. The lineup was Nicky Carter, Olly Scott, Jane Walker, Paul Kean and Mark Wilson.

One Friday night at The Gresham, The Detroit Hemroids played to a crowd that included a young Roger Shepherd, who had been working at The Record Factory in Colombo Street since applying for a summer holiday job there in 1976. As he wrote later, that hour between the shop closing at nine and the pub closing at 10 was life changing and “my first real experience of live music played in a confined space and the sense of excitement that could be generated”.

Shepherd says his introduction to Christchurch bohemia began in the shop.

“I started meeting interesting people, art people, who would come in – you just meet all these people who come through the store and tell you stories and you talk about all kind of shit. It was always about the chat. That's kind of how record shops work.

“I remember being 16 and going to this grown-up party in town – and it was damn sophisticated. People dancing to the Bryan Ferry solo albums – which was sophisticated at the time – and talking about books and art. You could talk about those things in Christchurch in a way you couldn't anywhere else.

“The Gresham was a lot of the same people. It was astoundingly seedy. It was kind of failing and that’s why those bands got to play there and why that crowd was there. There were men kissing. There were people who were just plain weird and people who were dangerously weird, mixing in together.”

Ian Dalziel collection

The Gresham was demolished in 1978 and Mollett Street had the short life of all good punk rock clubs. But Mollett Street stayed open long enough to a gig by The Enemy, which Shepherd recalls as a big night for everyone there. It was also the beginning of Shepherd’s enduring contact with Dunedin’s music. (The Enemy would play Mollett Street twice, the second time bringing a new band, The Clean, with them.)

“Punk itself was a horrible nasty little stuck place, but the inspiration wasn’t necessarily just musical – it was attitudinal,” Shepherd recalls. “The Enemy were the band. They sound ponderously slow and sort of weird now, but they had a huge impact. It was, oh my god, this is the real deal, this is a real band. And no one had any doubt.”

Jane Walker, June 1978 - photos by Kevin Hill

By 1979, the Gladstone Hotel, the Hillsborough Tavern and the brilliantly sleazy British Hotel in Lyttelton were booking local bands.

It hadn't always been easy to find a place to play original music in the city. Entertainment in pubs controlled by Lion Breweries was booked by Trevor Spitz, a former 60s rocker who had a stable of cover bands shuttling around and usually playing a different place each week. But DB establishments had a freer hand and by 1979, the Gladstone Hotel, the Hillsborough Tavern and the brilliantly sleazy British Hotel in Lyttelton were booking local bands. Makeshift venues like Wayne Manor, upstairs in the former Sydenham Fire Station, and the England Street hall in Linwood provided more unruly places to play and hear music.

By 1980, the city was flush with bands. Some, like The Androidss, the ultimate good-time group, drew big, thirsty crowds when they came home from Auckland. Others, like the Victor Dimisich Band, Montgomery’s own Pin Group and Bill Direen’s group, The Vacuum, were more niche tastes. But they all had places to play and people to play to.

“[Promoter] Jim Wilson was responsible to a large degree for how that whole live thing worked in Christchurch. I think he actually did develop it rather than just exploit it,” says Shepherd.

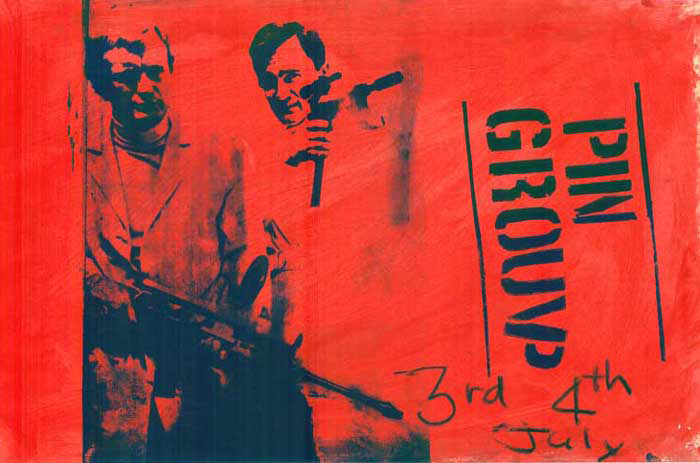

It was more than rock ‘n’ roll. If Auckland had its art-school punks, in Christchurch, the art was often indistinguishable from the bands. Direen produced theatre, The Pin Group were on the bill at a Dadaist event at The Arts Centre and wrote with poet Desmond Brice. Wayne Manor could host a post-punk band one week and a poetry happening the next.

Ronnie van Hout, the most notable Christchurch artist of his time, created brilliant screen-printed posters for The Pin Group, Playthings, Mainly Spaniards, 25 Cents and others. He also shot a distinctly Warholian film featuring Brice, The Pin Group and fellow painter Marty Whitworth.

The most singular group to emerge from Christchurch, The Gordons, included graphic designer John Halvorsen, who created a graphic identity that expressed the same aesthetic as their uncompromising music.

“I watched John Halvorsen doing some of those early Gordons posters and I thought my head would split,” Wilson, a billposter both before and after he was a promoter, wrote later. “Every time I put one of them up, I felt something through my total body ... a streaming. I was coming alive.”

The Gordons at The Gladstone, 1980 - photo by Gordon Bartram

One remarkable aspect of the scene was its accessibility. As schoolkids, my friends and I chatted to Shepherd, Montgomery (EMI Shop) and Peake (University Bookshop) at their respective record shops, got to know most of the bands and, most of the time, gained entry to the pubs where they played. There were many characters and no end of places to encounter them, but not much of a star system.

But what the city lacked was a record label to record and release it all. Not everyone was as together as The Gordons, who funded and released their Future Shock EP and startling self-titled debut album themselves. Not everyone was popular enough to decamp to Auckland and hook up with Ripper Records like The Androidss. Something needed to happen, lest it all go off into the ether.

In late 1980, word went around that something was happening. Roger Shepherd, still the laid-back friendly guy at The Record Factory (Montgomery managed the opposition EMI Shop on the other side of the Square), was to start a record label.

Montgomery wryly told The Big City in 2012 that Shepherd started a label because that was all he could do:

“You’ll have to ask Roger but I think he got to starting a label by a process of elimination. If you were not going to be in a band but you were not content to just stand there and watch your friends embarrass themselves in bands what else could you usefully do which no one was doing? Band managers were rated about as highly as car dealers. Label owner in the mould of Rough Trade seemed worthy to all and sundry at the time.”

“There's a degree of truth in that,” Shepherd agrees. “You were kind of involved and eventually had to feel useful. But I think having that retail background, I had a reasonable idea of how to sell records. It transpired that the only thing that was hard about making records was trying to get the pressing plant to take you seriously enough to prioritise you and actually make them.

“I was definitely inspired by what Bill Direen was doing and by The Gordons, who were very special to me. It was very much about the live thing – you responded to seeing those bands live. There were all sorts of people doing things. I spent an awful lot of my life at The Gladstone at that time. I liked The Gladstone a lot, it was pretty special.”

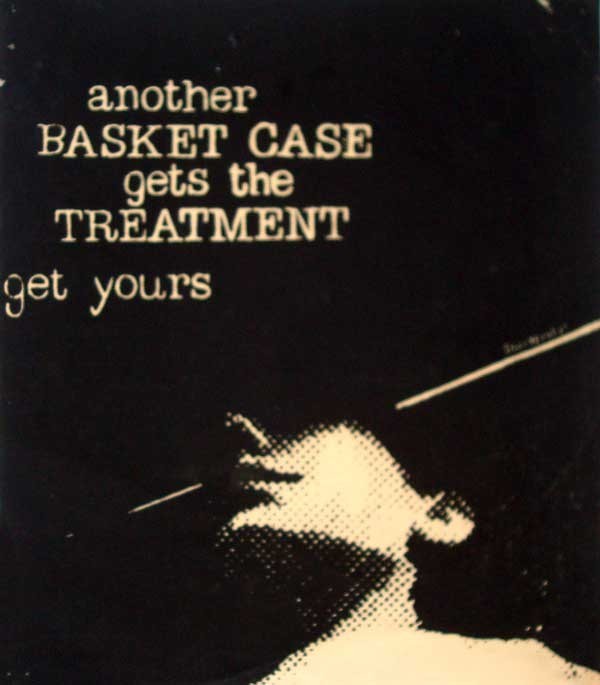

The very first Flying Nun advert

Fittingly, Flying Nun’s first release came from the Christchurch underground: it was The Pin Group’s ‘Ambivalence’/ ’Colombia’, in a memorably bleak black-on-black sleeve by van Hout.

But the next release, by a whisker, was The Clean’s ‘Tally Ho!’, the product of the links Shepherd had forged with Dunedin’s musical community after seeing The Enemy. In the years that followed, the Christchurch label became tied to the music of Dunedin, even though Flying Nun also released The Playthings, Victor Dimisich Band, the Bilders, Mainly Spaniards and others from the scene that was flourishing at the time it was born.

“The thing with the Dunedin part of the label, which came to dominate, was that we were being exposed to it,” says Shepherd. “And again, Jim Wilson had a lot to do with that. He was the one offering them money and an audience in Christchurch – which a lot of those bands didn’t have in Dunedin.”

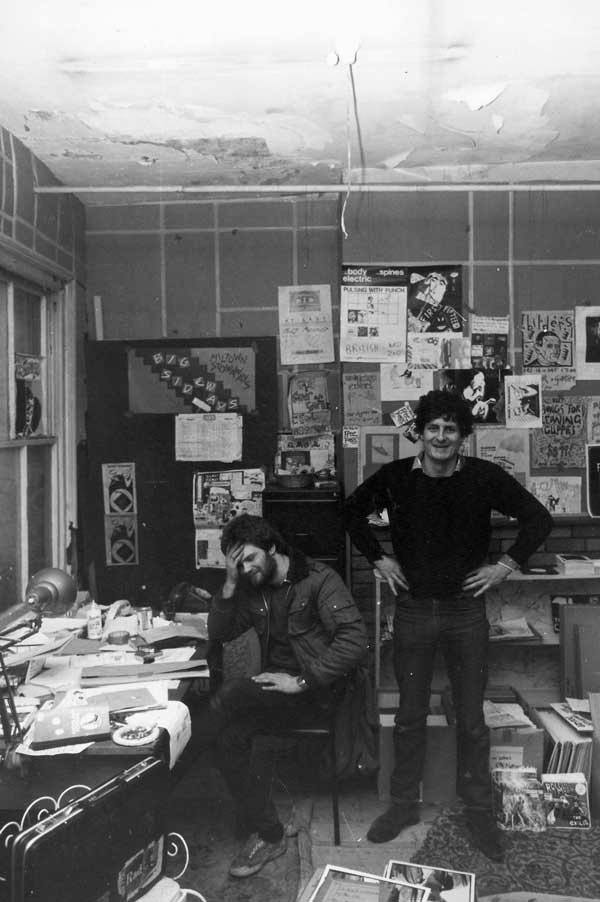

Roger Shepherd and Hamish Kilgour in the Flying Nun offices, Christchurch, mid-1980s

It’s only in recent years that music historians like Bruce Russell (who curated the brilliantly-annotated compilation Time to Go) and Canadian author and publisher Matt Goody have reinterpreted the Flying Nun heritage in terms of the strange music and stranger culture that surrounded its birth. What they have shown is a very different Flying Nun. A Flying Nun that very definitely came from Christchurch.

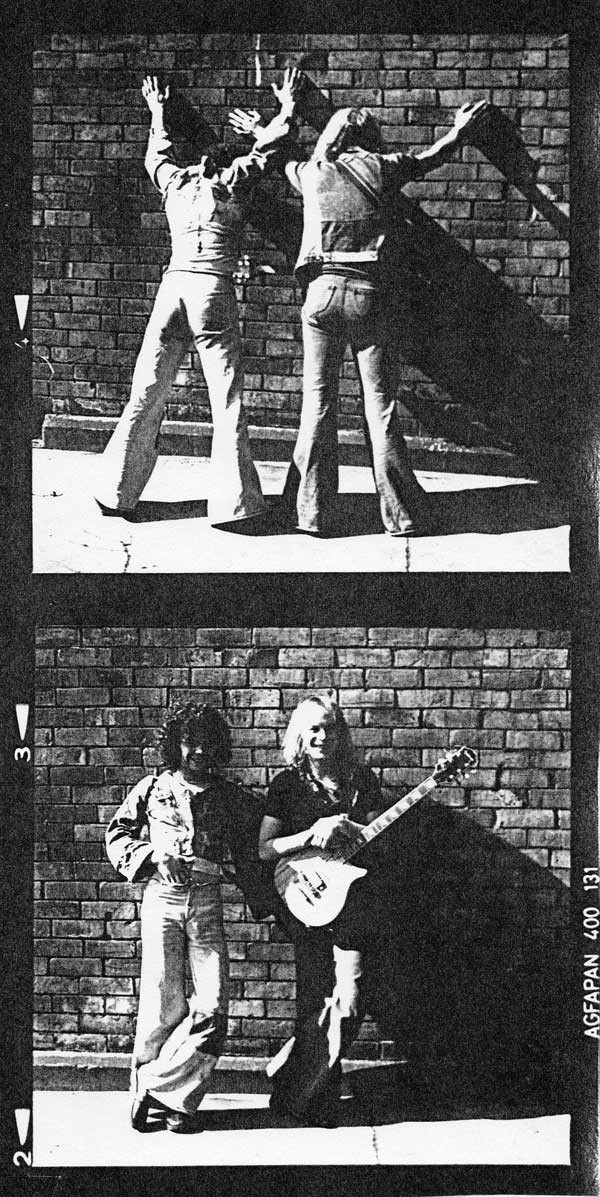

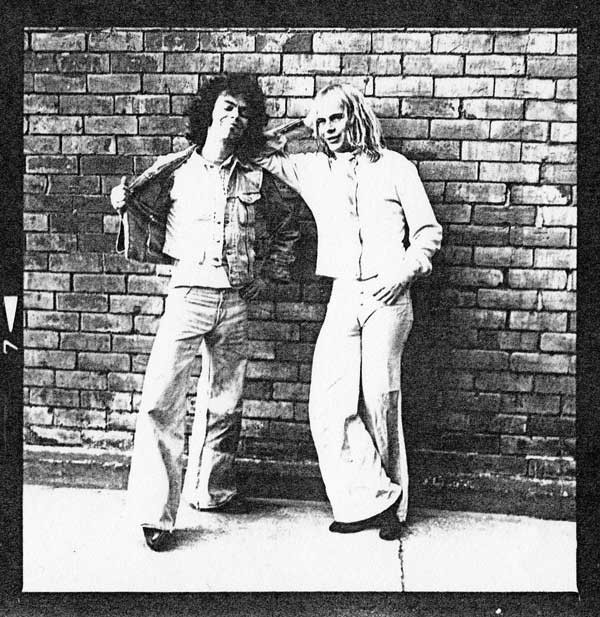

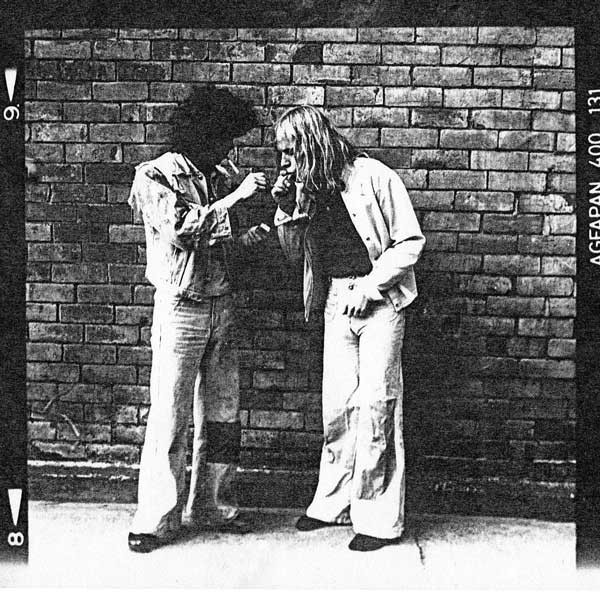

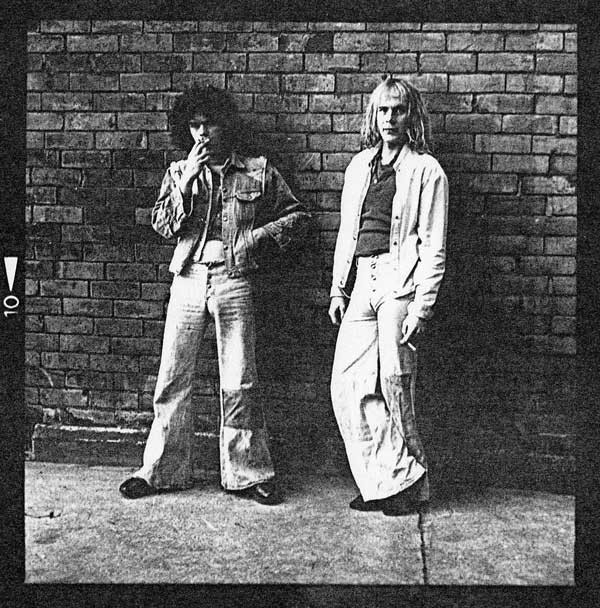

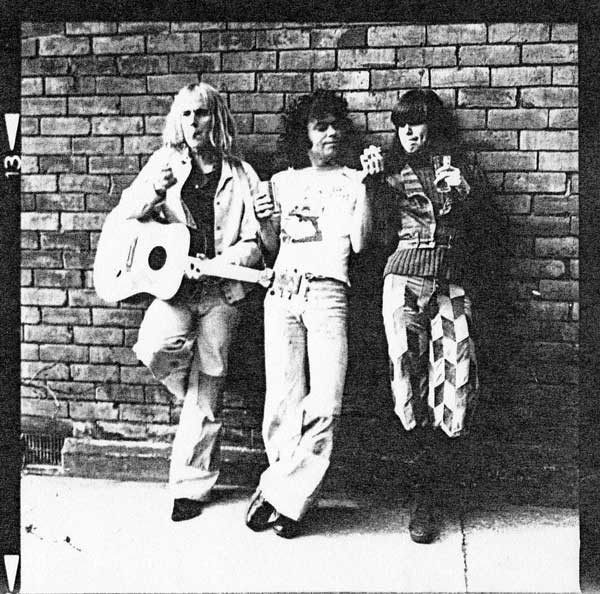

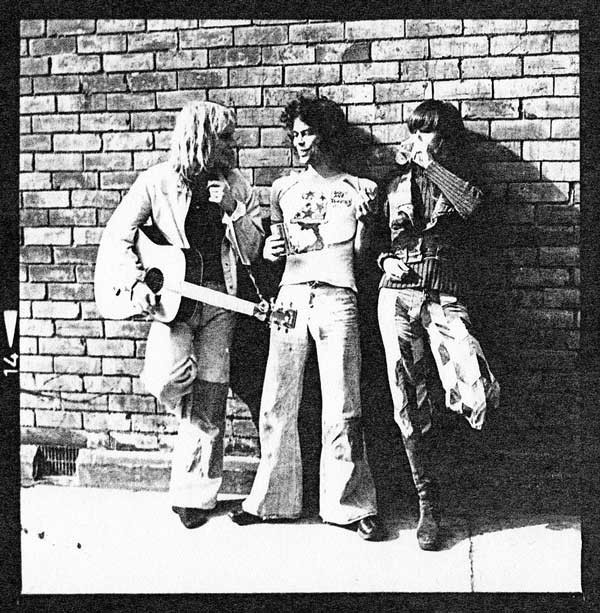

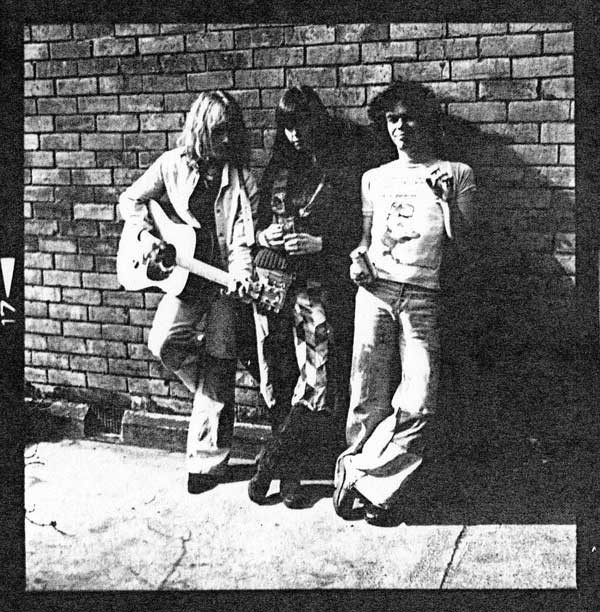

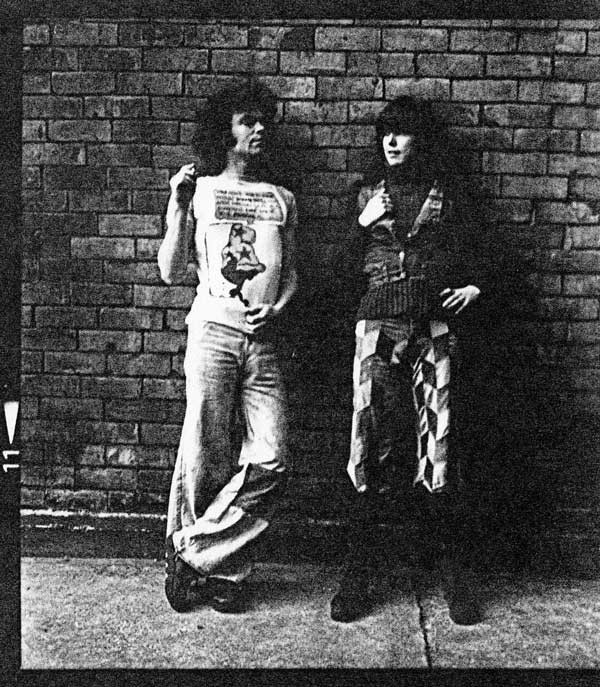

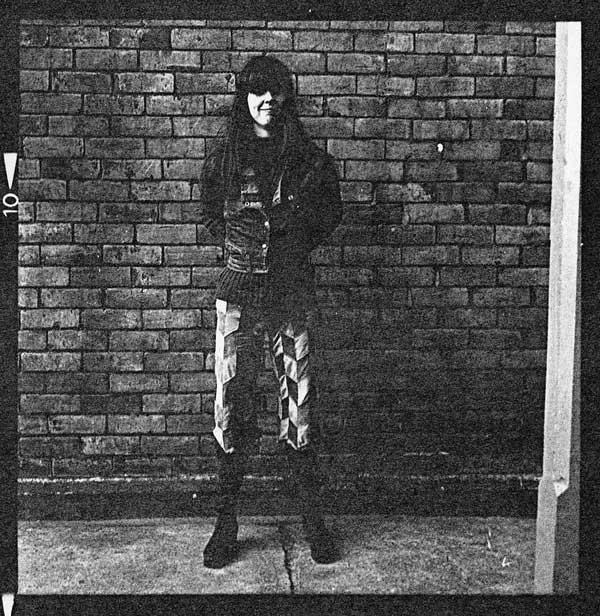

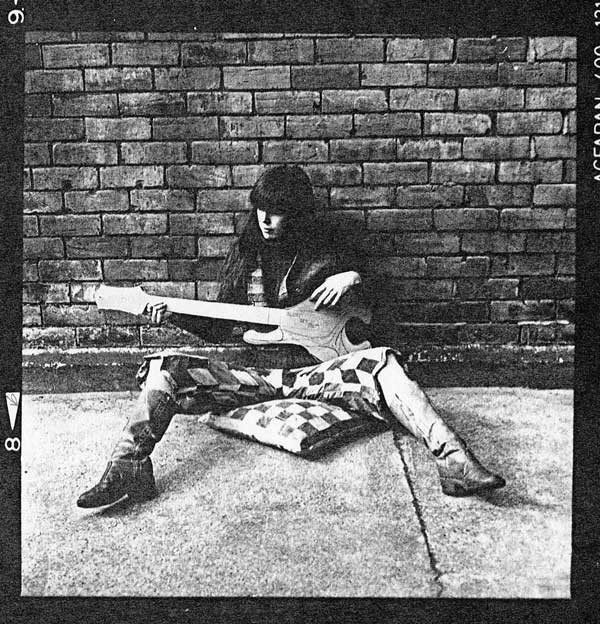

The Detroit Hemroids images

From Jane Walker's archives comes these images, taken by Peter Towers, of Jane, Nicky Carter and Olly Scott in Christchurch, c.1978 in Mollett Street.

Olly and Nicky

Nicky, Olly and Jane

Nicky, Jane and Olly

Olly and Jane

Jane

–––

A Robin Mcilraith video of Ollie Scott, Paul Kean and Dave Toland in Ollie's backyard, Christchurch 1988.