AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Dominic "Tourettes" Hoey

aka Tourettes

“I was about 14 and my mates were already playing music. There was already a guitarist and bass player so I started playing drums. I got lessons, but it was off a dude who is an amazing drummer but it was all marching shit. So it wasn’t really that applicable to playing punk beats. We would’ve been 16 or 17 when we started playing punk shows with Balance and Nothing At All!. I was in bands called Pink Youth and Scrumptious, plus a few others where we only played a few shows. Then Witness – we did a lot of shows. I was rapping the whole time, but it wasn’t until Witness broke up that I started doing that more seriously.”

5th Floor

In 2000, Hoey moved to Wellington where he began jumping up to rap at punk shows or freestyling at house parties. It was a difficult to find beats to rap over, but eventually Hoey hooked up with a connection from the punk scene to form his first serious group, 5th Floor.

“Dave Brown made the beats for 5th Floor. He was originally in a punk band [Blake] who Witness performed with. They were around for ages. He was connected to Wellington hip hop scene, which was more advanced than the Auckland scene at that time – I guess it was a smaller place, so you’d go somewhere and there’d be 100 people who were rapping and doing their shit. Through that we met the other members of the group.”

The early line-up of 5th Floor included MC G Whizz (Glen Kowalski) and DJ Buttafingaz (Harlin Davey). The crew began playing regularly at venues like Valve and the original Bodega, doing both punk and hip hop shows, as well as performing at parties. As their ambition grew, they decided to relocate to Auckland where the group expanded to include Jeremy Toy, Bjorn Petersen, and Julien Dyne (who’d originally met Hoey through the punk scene, when Dyne was drumming in Diecast). Their growing acclaim on the live scene put undue pressure on the young group and Hoey found the members pulling in different directions.

“It was cool, but it probably happened too soon. We got a lot of attention really quick, which kind of led to it imploding. Jeremy Toy, who was doing all the music was into that jazz way of doing it where they’d only practise before the show and maybe they were good enough musicians to do that, but the rest of us weren’t.”

Breakin Wreckwordz

In 2001, Hoey followed his friend Jared Abbott (Cyphanetik) to Melbourne and attempted to get a foothold in the scene there. Yet they struggled to find local hip hop crews that they wanted to do gigs with. Instead, the pair stayed home and honed their skills.

“We just started rapping all day, every day, which was probably what I needed.”

“We just started rapping all day, every day, which was probably what I needed. Those first few years, all I’d done was freestyle so I was real good at that, but I had to catch up on the whole other side. With rapping, it’s not like playing an instrument where you can go get lessons or read a book about chops. You have to just learn it by doing it. We didn’t even really play shows – we just did a couple of house parties, but we were just rapping and recording for a year pretty much.”

The pair lived in a three-bedroom flat, which had up to 10 New Zealand expats living there at a time. One of their fellow tenants was Saan Barrett, who’d begun producing beats as “Aardvark” in the back shed. Hoey found that Barrett’s odd production style led he and Cyphanetik to push their style in a new direction.

“At that time, there was an unwritten code that if you sampled you had to sample vinyl and you were meant to use this certain equipment and so on. But instead he was sampling off cassette tapes and VHS. It sounded real cool, so that’s when I moved away from that four realms hip hop that was real prevalent at that time. I’d got real stuck in that. So I got back to why I started doing it, because it’s such an amazing form of expression. Rather than getting stuck in the clique of it.”

Tourettes and Cyphanetik formed The Insomniacs and sent a demo of their track, ‘Hey Kids’, to Dubhead, the programme director at 95bFM. They intended just to raise his interest, but he immediately playlisted the track (despite the sound of kids crying and people doing dishes in the background). The hype around the track also led them to be approached by Lio Nikolao from Shock Records, who wanted to release their music. The pair then worked with Shock to start their own label, Breakin Wreckwordz.

“Jared kept on yelling out ‘Breakin Wreckwordz’ at the start of our songs and eventually he explained to me that this was going to be our collective, our record label. I was always a big fan of Factory Records and was telling him about that, so we based it on that model where it’s a 50-50 split and everyone is equal. Which in retrospect probably doesn’t work, not in New Zealand anyway. At that time, everyone who went on to do stuff in local hip hop was on the hiphopnz forums – like David Dallas and the Deceptikonz. Jared was more part of that than I was. I preferred the live thing than getting on the internet. So he’d connected with Louie Knuxx and his crew, Dirtbag District and Usual Suspects. His plan was to bring them all together on our label.”

The pair returned to Auckland and got their names out on the local scene by taking part in the MC Battle For Supremacy – Tourettes won the New Zealand final in 2003 and Cyphanetik won in 2004. It was at this event that Hoey first met another long-term collaborator.

“Jared was so big on hiphopnz – everyone was bigging him up and not paying me any attention. He was like, ‘you should just battle someone,’ so I battled Todd [Williams aka Louie Knuxx]. But then when I met him, I had this huge beard and long hair. At that time, no one had beards really so I looked pretty weird I guess. So I went up to him and said, “Hey I’m Tourettes” – and he said – ‘no you’re not’. Then he stormed off. But we ended up living together not too long after that.”

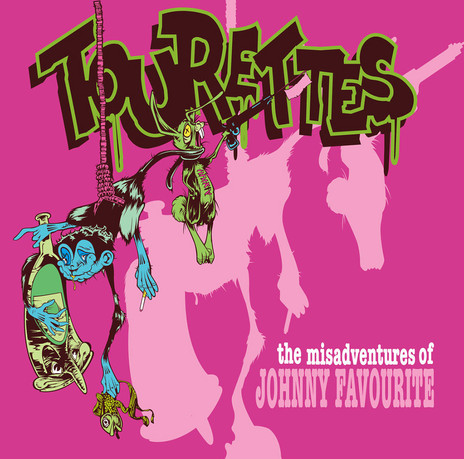

Johnny Favourite

Breakin Wreckwordz Vol.1 (2004) compilation officially launched the label and featured: Tourettes, Cyphanetik, Insomniacs, The Usual Suspects, PNC, Tyna & JB, Quest, Louie Knuxx, Kwierist, and Frontline (including Con Psy aka David Dallas). The following year, the first Tourettes solo album came out – The Misadventures of Johnny Favourite (2005), which saw Hoey taking inspiration from the movie Angel Heart, and presenting Tourettes as his troublemaking alter-ego.

Saan Barrett had recently returned from London prior to the recording of the album and supplied a new CD of beats (produced under the name, “Hero”) from which Hoey created three tracks. However, the majority of the album was produced by a young producer that Hoey had been introduced to.

Hoey felt pressure to do a single that might cross over.

“Jared just met 22 [Roddy Kirkcaldy aka Scratch 22] on the street. He was like 17 or something. The only thing we’d heard about him was that he’d dissed out Deceptikonz or Dawn Raid online and there was all this beef. I’d never heard his beats and then Jared took me to his place. He was going to uni, so he was just in one of those student apartments. His shit was real good – perfect for what I wanted to do – so we instantly started making tracks.”

In the meantime, the local hip hop scene had blown up and Hoey felt pressure to do a single that might cross over (and would allow him to get NZ On Air funding). He came up with the catchy, slacker hip hop track, ‘Lovable Losers’, with a chorus sung by Richie Simpson (from New Way Home). The accompanying music video showed Hoey being pushed around in a shopping trolley by street artist, Elliot Stewart aka Deus (who also did the album art). Looking back, Hoey is dismissive of the track but it had the intended effect of pushing Tourettes to a wider audience.

Breakin Wreckwordz was also given a boost by the buzz around local hip hop, and artists from the roster worked together as a crew to perform at the Big Day Out and Aotearoa Hip Hop Summit. CD releases on the label were reliably selling 1000-2000 copies and new acts were gradually being added to the roster, including Red Eye Society (RES), Jay Roacher, Tyson Tyler, Cancer, and Oddballz.

Who Said You Can’t Dance To Misery?

By the time of the second Breakin Wreckwordz compilation, It’s A Monster (2007), the glow around the New Zealand hip hop scene had begun to fade. Hoey had also had a miscommunication with Shock Records that caused difficulties when it came to his next release.

“Give Me Five Dollars And I’ll Show You My Dick was just meant to be this mixtape and then I was going to do a fully-fledged album, Who Said You Can’t Dance To Misery? (2007), six months later. But Shock put out Give Me Five Dollars as a proper release even though it wasn’t really album quality and then they told me that I couldn’t put my other album out until I’ve promoted that one. It just fucked up the momentum of everything. Quite a few people really liked the first album then that came out and it was like a step back.”

The same year one of his poems was published in New Zealand’s most lauded literary journal, Landfall.

In the end Hoey arranged for the distribution of Who Said You Can’t Dance To Misery? via Rhythmethod (though still under the Breakin Wreckwordz moniker). It received a great critical reception and became Tourette's best selling album, as well as producing one of his most enduring tracks, ‘Almost Out Of Water’ (featuring Anna Coddington). Hoey wrote the track to be a single, but this time worked hard to “write a radio song that had some substance to it” by incorporating lessons from his growing interest in poetry. The same year one of his poems was published in New Zealand’s most lauded literary journal, Landfall.

Hoey had a deal lined up to release his second album in Australia and even had a manager in place, but it fell apart at the last minute and he moved back to New Zealand. These difficulties left Hoey feeling more inclined to play drums in alt-country group, The Vietnam War, than to play his own rap gigs.

“I kinda just stopped doing my own shows for a while. It went from us playing at 420 in front of 500 people to gigs where there’d be seven people. Hip hop stopped being cool. I was in The Vietnam War so I thought – I’ll just play with these guys instead. It was actually Matthew Crawley that said, ‘you’ve gotta start playing live again.’ So I started playing at Whammy and there’d be two hip hop acts and two punk bands or whatever. It sounds totally normal now, but at the time it was like, ‘you can’t do that.’ It took me a while to convince Rohan it was a good idea. But they were really cool gigs.”

Hoey’s involvement with The Vietnam War came through the band’s lead singer, Lubin Rains.

“I’ve been friends with Lubin since I was 14. We went to Western Springs together, then all got kicked out and went to Metro for the last three years of high school. I met Lubin because we were both rapping, though we were really bad. He came up to me afterward and said, ‘do you wanna be in my rap group?’ It was really funny – there was him with his long hair and his two little mates. It was so unlikely. He said, ‘this is my rap group, Home Squeeze.’ I wasn’t sure about it, but we started rapping together. It ended up providing a weird premonition of what was to come, because we wanted to do this fun thing, but then it immediately went sour.

“The second time we had rap practice, a whole bunch of gang prospects turned up and tried to smash their way into the house, so we had to climb out the window and run away. It does remind me of what eventually went on at Breakin Wreck. I think it’s changed now but in New Zealand there was always a tie between rapping and criminality. I remember a lot of shady shit going on at Breakin Wreck and I’d always just be thinking, I just want to write rap songs about my love life and I’m being involved in this shit. People were punching people. It’s weird with the industry, they want poor people acting dangerous, but when they actually act poor and dangerous, they don’t want that. With Breakin Wreck, it was one of those things where if we knew then what we know now, it could’ve been completely different. We had so many amazing artists, but just struggled getting the infrastructure together. Also, Todd had burned bridges, I’d burned bridges, Jared had burned bridges. By the end, we burned every bridge that existed. We did a lot of dumb shit and the industry kinda closed ranks on us. When bFM wouldn’t even play our shit, it was like ‘oh fuck it.’

Tiger Belly

In the meantime, Hoey had also begun work on what would become his third album, Tiger Belly (2011). He originally intended it as a side-project in collaboration with Saan Barrett, but when the process dragged on for four years, he realised it would be better to release it as his official third album (on Round Trip Mars). His previous albums both included spoken word tracks, but now he pushed this element of his work and even produced one track, ‘Caspa And Alice’ that was eight minutes long and took the form of a poetic short story.

“Saan just kept giving me stuff and I kept writing to it. Often with poetry I tend to think less is more and try to keep it quite short, but if the beat is five minutes long then you start stretching it out and stretching it out. New stuff would keep coming to me from that. I’m actually working on a new poetry book at the moment and I’m getting people to send me beats to write to, just to get that same effect, even though I might never use them – it just pushes you.”

On Tiger Belly Hoey also worked with two other musicians, who he met through Lubin Rains: Caoimhe MacFehin (Rains’ sister) sang on the album and Karl Steven (Rains’ eventual brother-in-law) produced the album. This connection also led to Tourettes and The Drab Doo-Riffs doing a split 7”. Steven also encouraged Hoey to add a couple of lighter tracks to the album (e.g. ‘Everybody Loves Tourettes’) since the original demo version was a very dark listen.

Hoey had also been diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis – a form of autoimmune disease.

In retrospect, Tiger Belly shows Hoey perfecting his skills at spoken word and opening a new career path for himself, but at the time he was sorely disappointed with its reception. “It kinda flopped – no one was playing it and no one would review it.”

The previous year, Hoey had also been diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis – a form of autoimmune disease, which can make it very difficult for the sufferer to move freely. Fortunately, a new opportunity came along just in time.

“I’d been living in Melbourne, but came back to put out Tiger Belly. Then I got accepted into the writing residency in Iceland, so I went back to Australia to save up some money ... I guess my disease helped with writing the novel because it meant I couldn’t do anything for a year. Maybe I would’ve gone back to rapping if that had not happened, but it just meant that it was not really possible.”

Looking Great

In 2013, Hoey joined Sam Hunt for a performance at Golden Dawn which gave him access to a new audience that no longer expected his pieces to be accompanied by a beat. The following year, he supported Hunt at the music festival, Splore. Without intending to, Hoey gradually began accumulating the pieces that would become his album, feel like shit, looking great (2016).

“I was living with Abe [Abraham Kummin] and he was just always making beats so we did that song, ‘John Key’s Son’s A DJ’, and it took off. We didn’t even do a proper video. I went to Splore [in 2015] and performed it, then someone filmed it and put it on YouTube. It ended up getting over 10,000 views so we thought ‘fuck we better put this out now.’

The album only included one rap track (‘Cancer vs. Heart Attack’ feat Jay Roacher) and instead took influence from the experimental electronic artist, Burial. Hoey’s approach to his own writing had also expanded to push beyond the personal into tracks where he felt he was speaking for others who’d had similar experiences, especially on the track ‘No Losers At WINZ’.

‘I’ve been on and off benefits my whole life – most recently the sickness benefit when my disease started. There was so much benefit bashing in the press all the time and I’d always think – if you had any idea how hard it is to be on a benefit, there’s no way you’d write that. It’s like a fulltime job dealing with those people … There’s this one woman who has been there since I was 18. When I went in to get on the sickness benefit, she was still there, still giving me shit. I thought – why are you hassling me, when you’ve been in the same dead-end job your whole life? I’ve toured the world, I’ve released albums and books, what have you done? … At that point, I wasn’t on the sickness benefit any more, but I still just wanted to capture how I’d been treated since I knew there was so many people out there who had been through the same thing.”

Hoey’s move towards spoken word has opened up new avenues on the live front too. While touring with Luckless [Ivy Rossiter] in the South Island, she pointed out that there was a touring circuit of the smaller towns in the New Zealand that he might want to try (despite usually being frequented by folk artists). This inspired Hoey to undertake increasingly wide-ranging tours of New Zealand, touring with solo acts like Luckless and folk-bluesman Skyscraper Stan.

Hoey looks back on his early career as a time of missed opportunities, but is still grateful with the final destination he ended up at.

“I’ve [done] a lot of cool shit over the years. I was hanging out with Coco Solid a while ago and talking to her about how when you’re in your twenties, being a rapper is the best thing you can do because you get to meet people and travel and do all this cool stuff. But I feel really blessed that I had poetry and writing to segue into, because I do know a lot of people whose whole life revolved around rapping, but now they’re my age and there’s nothing they can do with all that talent because it’s a young person’s game. I’m pretty proud that I achieved so much by myself, even if I did have dozens of people helping me along the way. Still, I was the one who had to keep it all going and keep pushing forward to do new stuff.

“I’ll meet young people now and they’re like ‘you influenced me’ to do this or do that. You don’t think about that at the time, you don’t even know if anyone is listening to it. So it’s really cool to know my work was having that effect.”

Dominic Hoey's book, Iceland, is featured on the longlist in fiction category for the 2018 Ockham New Zealand National Book Awards.

In 2012, Tourettes rapped on the Home Brew track, 'Listen To Us', which attacked the National government of the day (Matthew Crawley and Esther Williams also featured on the song).

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air