A song for Bowie’s POW film

Stephen McCurdy was very prolific as a film composer during the 1980s. His background set him up well for a career in the field. Since the 1970s he had been a composer and musical director in theatre, and he created music for several hundred television commercials. His first taste of film scoring was in the early 1980s when a musical piece was needed for a child character in Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence. The film, directed by Nagisa Ōshima, was mostly shot in Auckland. Its main composer, Ryuichi Sakamoto, was in the country shooting because he also had a major acting role in the film as POW camp head honcho, Captain Yanoi.

Even though Sakamoto was in Auckland, Stephen McCurdy was asked if he was able to provide the lyrics and tune for a song to be sung on screen by a child character in the film. He said yes. McCurdy’s short, sentimental and rather moving song is heard twice in the film as POW Major Jack Celliers (David Bowie) thinks back on painful childhood memories about his younger brother.

The song is first heard as Celliers’s brother wanders through a garden singing this little song he has composed himself, to a backdrop of synthesisers. In another memory the boy sings his song again, this time a cappella, during a cruel and humiliating school initiation in which he is forced by a large group of older boys to sing. The version of McCurdy’s song with the synthesiser backdrop was included on the Virgin-released soundtrack under the name ‘Ride, Ride, Ride (Celliers’ Brother's Song)’ alongside tracks from Ryuichi Sakamoto’s evocative score.

Taranaki caper

Stephen McCurdy’s first feature as sole composer was Ian Mune’s directorial debut Came a Hot Friday (1984). The comedy was based on the 1964 novel by Ronald Hugh Morrieson, the former dance-band musician from Hawera. Morrieson’s “grim tale featuring two conmen who gamble and drink their way across Taranaki” (NZ On Screen) was dark and often violent. Mune’s treatment of the source material, along with Billy T James’s beloved performance as the Tainuia Kid and McCurdy’s music, helped soften the darker subject matter of the novel into a light-hearted comedy.

Set in rural New Zealand in 1949, the film’s 40s-style country and jazz-influenced soundtrack featured contributions from local veteran jazzmen Crombie Murdoch (who had written the words and music of the 1957 hit ‘Opo, The Crazy Dolphin’) and bass player Andy Brown. The opening track ‘This Time’ was sung by Beaver and the film’s other two songs, ‘Work for the Money’ and ‘Out in the Cold’, were sung by Prince Tui Teka, who also played saxophone.

Came a Hot Friday won the film-score award at the 1986 National Mutual GOFTA awards. After the film’s release, McCurdy revisited two of its songs for release as singles, but Prince Tui Teka passed away before his recordings could be completed.

Trans-Am action flick

McCurdy’s next score was for Bruce Morrison’s high-speed action feature Shaker Run (1985). In Morrison’s self-described “fantasy car violence” film, a down-on-his-luck former racing car driver-turned-stuntman and his friend go on the run in their pink and black Trans-Am, named Shaker. A deadly biological weapon is in their possession and the shady New Zealand Security Service on their tail. The film’s $5.3 million budget was massive by New Zealand standards of the day.

McCurdy’s score had 80s action-appropriate attitude in spades to bolster the film’s numerous stunt sequences and explosions. There’s plenty of saxophone, flashy electric guitar, sampled instruments, punchy drum machine beats, and rich analogue synth textures. McCurdy’s music is used sparingly throughout the film, though. He says, “I think the tendency for New Zealand screen music is to be quite sparse ... and that’s a good thing. Part of my job is knowing exactly when to sit on my hands.” (NZ On Screen).

Shona Laing also contributed a song to the film. A bar scene in Shaker Run shows Laing with a band on stage giving a dynamic performance of her song ‘America’. A decent chunk of screen time is dedicated to them and there are plenty of close-ups of the keyboardist’s hands playing his Korg Trident Mk II. (Though perhaps this is more for show, as the synths in Laing’s music video for the song are different.) Laing wrote ‘America’ after returning from stints in the US and UK, and it was the first release on Trevor Reekie’s newly-formed label Pagan.

McCurdy went on to compose chamber music for the Katherine Mansfield-inspired drama directed by John Reid, Leave All Fair (1985), and synths and songs for Ian Mune’s thriller Bridge to Nowhere (1986), one of McCurdy’s only other soundtracks to be released. McCurdy also composed the faux Peggy Lee song that opened each episode of 80s Kiwi TV soap Gloss.

Pagan Records, launched by Mirage Films, released albums of music from Bridge to Nowhere and Bruce Morrison’s Queen City Rocker (1986). Although Dave McArtney wrote several songs for Queen City Rocker, both films can be considered pioneering examples of “songtracks” rather than soundtracks. The films had a secondary purpose of giving exposure to current acts, including several in Pagan’s stable such as Ardijah (who have a live performance scene in Queen City Rocker), Shona Laing, and Tex Pistol (Ian Morris). Singer Kim Willoughby played a lead role in Queen City Rocker.

“A Kiwi riff on the European art film”

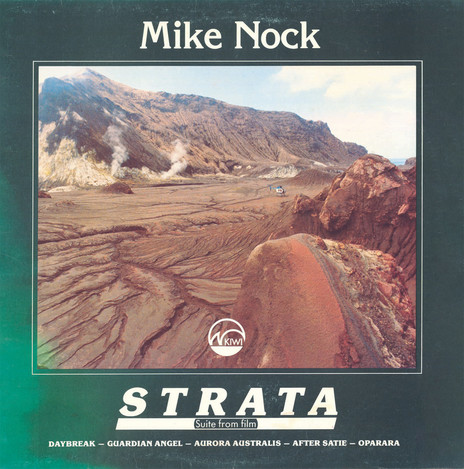

With a score by Christchurch-born jazz pianist Mike Nock, Geoff Steven’s psychological thriller Strata (1983) has been called a “Kiwi riff on the European art film” (NZ On Screen). Set around the arid volcanic North Island central plateau, two groups of travellers clash on this barren landscape.

In an Art New Zealand article written shortly after Strata’s release, Rosemary Hemmings wrote, “Music, composed and played by New Zealand jazz pianist Mike Nock … is an important element in the film. It is used to add texture and depth to the characterisations, and to extend the surreal quality of the images. Nock fitted the score to a video of the film, working on acoustic piano, when he came here recently from New York.”

Not only did Nock play acoustic piano but also a Fender Rhodes and a Prophet 5, the coveted early 1980s synth made by Sequential Circuits and used on countless 80s albums and soundtracks. The Strata score, recorded at Broadcasting House in Wellington, included percussion by influential jazz drummer, Roger Sellers.

The Strata score was nominated for soundtrack/cast recording/compilation at the 1984 New Zealand Music Awards.

Dobbyn’s “alternative national anthem”

Dave Dobbyn originally thought the producers were kidding they asked him to score Footrot Flats (1986). He thought they probably just wanted a couple of pop songs. But once he realised they wanted him to compose all the incidental music as well as a song for each of the main characters, he hunkered down in his small home studio and got on with the job. The film’s animation hadn’t been created yet, so at first Dobbyn worked from Murray Ball and Tom Scott’s script.

This was the mid-1980s. DD Smash had recently split up and Dobbyn was striking out on a solo career. In a 2021 RNZ interview with Yadana Saw, Dobbyn said the Footrot Flats project was his only source of income at the time. “It was a real relief, you know, to be able to do something where you’re just being creative all day long, sitting in a little room, staring at a tiny little LED screen, making sounds and making loops and trying to find noises that would suit the character.”

Murray Ball’s iconic Footrot Flats comic strip ran in New Zealand newspapers from 1976 to 1994 and proved the perfect subject matter for Aotearoa’s first feature-length animated film. It also seems unthinkable now that the score could have been written by anyone other than Dobbyn, though it was Tim Finn who was offered the job first. But he passed. Producer John Barnett said Dobbyn was always his first choice anyway, because he felt they needed a soundtrack that spoke to a younger audience.

In a 1987 Rip It Up interview with Chris Bourke, Dobbyn explained that because Footrot Flats was his first film score, he started off going in the wrong direction. “I wrote a few ditties that were parochial and cartoony, and the producers said, ‘No. Hold on. We want your music’ … so that was okay. I got stuck in and wrote how I’d normally write, not thinking about the movie at all.”

The song he wrote for the relationship between farmer Wal Footrot and hairdresser Cheeky Hobson started out as a jaunty tune, as Dobbyn assumed their relationship wasn’t serious. When Murray Ball explained that “it’s true love”, Dobbyn rewrote the song as a ballad and ‘You Oughta Be in Love’ was born. Ardijah provided the backing vocals to this, and a couple of other songs on the soundtrack. “Ardijah have a really light touch,” Dobbyn told Bourke. “I couldn’t believe their proficiency; when they started singing the blend was perfect.”

After hearing Herbs perform live in Australia, Dobbyn was so impressed by their capabilities to sing a cappella harmonies he asked them to do backing vocals for ‘Slice of Heaven’. “Herbs on ‘Slice of Heaven’ broke all sorts of rules technically,” Dobbyn said. “That uniquely Māori harmony of sevenths, ninths and 13ths all together … They sing as a vocal group rather than a bunch of vocalists.”

Although ‘Slice of Heaven’ wasn’t heard in the film until the end credits rolled, it was the song that captured the hearts of New Zealanders. It remained at No.1 on the New Zealand charts for eight weeks (and spent four weeks on the Australian charts). The song didn’t even have the benefit of being played on New Zealand radio until it was almost No.1. Dobbyn says it was incredibly difficult to get New Zealand music on the radio in the mid-80s as many radio programmers saw it as inferior to overseas music. Dobbyn later included the song on his 1988 album, Loyal.

Dave Dobbyn with Herbs, from the Slice Of Heaven recording and video shoot in Marmalade Studio, 1986

With Dobbyn’s vast experience in songwriting, creating the songs for the Footrot Flats score came easily to him. But the incidental music took longer. He even took a short, part-time course at the Australian Film Institute in Sydney on scoring for film. Dobbyn definitely knew what he didn’t want out of the instrumental music: “The last thing I wanted to do was get all stringy with swooping violins because that’s not the New Zealand countryside.” Once he decided upon a direction for the instrumental music, it was a slow process creating the sounds he had in his head using a library of sampled instruments from around the world and his Emulator II. This primitive sampler ended up playing an integral part in the score. “From various disks, I’d put together an ensemble of sounds. For example, an Indian tabla and the low notes of a piano – I’d put them on tape, slow it down, change the curves, get technical, doctor it all afternoon, and by evening I’d have the sound I wanted to hear.”

Dobbyn felt he needed to add some more dynamics to the rigid sampled material, so to avoid the expense of hiring an orchestra he decided to add guitar parts which he played himself. By this time there was animation to work from. “I used a lot more guitar than I thought. I could get some power and threat into that, and get expressive without being necessarily proficient or technical. I’m not a technician. I could just look at the screen and get a certain guitar sound.”

While some of Dobbyn’s sampler-made music for Footrot Flats hasn’t aged as well as the songs, the sounds Dobbyn wrestled out of his primitive Emulator II are certainly distinctive. The instantly recognisable earthy woodwind that opens ‘Slice of Heaven’ was created on the Emulator II as well, using a modified sample of a shakuhachi (Japanese flute). Both ‘Slice of Heaven’ and ‘You Oughta Be in Love’ will forever remain up there with the best New Zealand pop classics of the 80s. ‘Slice of Heaven’ has even been described as New Zealand's unofficial anthem. In 2020, Dobbyn recorded a te reo Māori version of the song with Hana Mereraiha.

In 1986 Dobbyn swept the New Zealand Music Awards with ‘Slice of Heaven’, including taking song of the year, and in 1987 he took best film soundtrack for Footrot Flats and best single of the year for ‘You Oughta Be In Love’. At the 1987 Listener Film and Television Awards he took best film score, and the film’s sound designer, John McKay, won best contribution to a film soundtrack for his work.

Dalvanius Prime’s subtle score

Ngāti (1987) is the story of a Māori community set in and around the fictional town of Kapua in 1948. It holds an important place in New Zealand film history as the first fictional feature film written (Tama Poata), directed (Barry Barclay) and scored (Dalvanius Prime) by Māori.

Dalvanius had been in the music game since the 1960s, founded his own production company, Maui Records, in 1983, and was pivotal to the success of Patea Māori Club’s ‘Poi-E’ in 1984.

The Ngāti score includes some unmistakably 80s electric bass and synth, but for the most part Dalvanius’s often beautifully haunting score is acoustic, subtle and restrained. The score includes cues of solo jazzy clarinet played by Tony Noorts, mysterious piano and strummed piano strings by Bob Smith, Dave Parsons on percussion, guitars by Rob Winch, and kōauau (Māori flute) performed by Clarence Smith. Traditional waiata are also sung by cast members on screen.

The film’s title track, ‘Haere mai’, was recorded with Cara Pewhairangi, a singer who Dalvanius mentored along with many other musicians throughout his career. Ngāti’s powerful score took best soundtrack at the 1987 New Zealand Music Awards.

Splatter music

The film usually called Aotearoa’s first completely homegrown, true horror feature is Death Warmed Up (1984), directed by David Blyth. So Mark Nicholas’s Death Warmed Up score could be considered Aotearoa’s first true horror score. It was the composer’s third collaboration with Blyth. After the controversial Angel Mine (1978), they collaborated on a tele-movie, the pioneer tale A Woman of Good Character (1980) about an English servant woman doing it hard on a rundown Canterbury sheep farm. Although this seems like an unlikely project for the Angel Mine creators, the film included unique innovations by both director and composer including what Blyth describes as “unusual musical sequences” involving “out-of-the-box” percussion.

Death Warmed Up – a splatter-fest sci-fi horror – was a return to what local underground film-goers might have expected from the pair. Nicholas’s synth drones and lively, sampled orchestral textures, with pounding timpani and Polynesian drums, plays a major part in bringing to life Blyth’s futuristic world. It was a civilisation in which killer zombies, a megalomaniac mad scientist, and suburban New Zealand meet. “The film really has held up”, David Blyth told me in a 2022 interview, “and I think Mark Nicholas’s genuinely original music is one of elements that makes the film successful.”

“The thing about Mark is he’s unique,” Blyth said. “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Evil Dead are two films that influenced me with Death Warmed Up. But, in a way, Mark’s music is completely original. And that’s what makes it so refreshing … He had a different way of looking at things. And hearing, if you like. And they were great years working with him. As they say, ‘Music is always part of the twin approach [of film]’. It’s visuals and music. And often music is providing the emotional base.’

Vocals for the songs in Death Warmed Up were performed by Annie Crummer and Peter Morgan with additional vocals provided by Wayne Laird (a NZSO percussionist who went on to found Atoll Records). Laird also produced the score’s recording.

Synth music as vital weapon

Wellington composer Michelle Scullion’s first major film project was the score for Peter Jackson’s debut: the low budget, sci-fi comedy-horror Bad Taste (1987). She had already made music for documentaries, short films, TV, contemporary dance works, radio drama, and corporate videos. Then in 1986 she got a call from Tony Hiles, who was helping an untried filmmaker complete an “unusual” project called Bad Taste. (NZ On Screen)

In a 2022 interview, Scullion explained to me, “What I saw was half an hour of a very rough cut with no sound. Peter, who I’d only just met, and Tony Hiles, his consultant producer at the time, were doing the sound effects with their mouths and I just literally, physically fell on the floor with laughter. That was my reaction: ‘Hilarious. Outrageous. Oh my God, this is so New Zealand!’ I could not believe what I was seeing.”

For research into the kind of score she might compose, Scullion said, “Peter wanted me to watch James Bond films, so I did. He loved James Bond films and so did I.” But she went away and listened to a lot of heavy metal too, thinking that might be the right direction for what she saw as such a “boys’ own, blokes’ movie”. She played cassette tapes of bands like Uriah Heap, Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin against video tape of the Bad Taste footage, but the combination never felt right to her. She ended up going in a classical-meets-synthesisers direction instead.

“In a lot of ways the score is genuine and earnest … and that’s because of the way the guys [in the cast and crew] were. They believed in Peter. They’d dig that weekend film-making.” This style felt better suited to the film’s main characters too, who she realised have a lot of heart. Once Scullion decided on the style, she says “it all flowed”. She created “probably far too many” demos on her Roland Juno 106 synthesiser for Peter Jackson to listen to – “40 ideas in 10 minutes in my lounge in my Newtown house”. She then performed her final score on an array of synthesisers, drum machines and a sampler.

To record these parts, Scullion worked with Dave Parsons in his small Aro Valley studio in Wellington. Parsons had used synthesisers in his own new age/ambient music (eg, Sounds of the Mothership, 1980) and knew how to conjure up great sounds out of them. “He was a synthesiser programmer, and I described to him the sound I might want and I’d challenge him. Then he’d challenge me to call up my own drum machine patterns. So Dave was very included and inclusive in creating the score.” Parsons also helped create faux-orchestral parts on a sampler. “There was no money for recording classical musicians,” Scullion explains.

With its synthetic and sampled orchestral textures, bombastic synth leads and funky 80s bass lines, Scullion’s score cranked Bad Taste’s B-grade gory fun up to another level. And with added electric guitar licks by John O’Connor and percussion by Roger Sellers, the score frequently pumps along as furiously as the blood pumping on screen. Though a more downbeat cue was Scullion’s choice for the infamous scene in which a roomful of aliens take turns drinking from a bowl of neon green alien vomit. “It was dinner, so of course it had to be soft café jazz music – and that was even before ‘café jazz’ was a term.”

Scullion’s Bad Taste score was nominated for best music at the 1989 New Zealand Listener Film and Television Awards. Remembering the ceremony, Scullion laughs and says, “We were up against all these famous films. Because there were so many categories Bad Taste was a finalist in – of which we won nothing – everybody who didn’t know me was being bombarded with my tracks [in the Bad Taste clips] all night!”

The film went on to win overseas awards and as NZ On Screen points out, “Scullion's exuberant, eclectic soundtrack proved a vital weapon in Jackson's breakout feature.”

After Bad Taste premiered at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival, it sold to 10 countries in six days and quickly gained a cult following. Scullion compiled her favourite music from the film and a vinyl picture disc of the soundtrack was released on German specialty label QDK in 1990, complete with a full-colour gun-wielding alien giving the finger on the A-side, and more gruesome delights from the film on the B-side.

Scullion assembled the album at Radio New Zealand along with engineer, Richard Hulse. “I took it seriously.” Scullion says. “It took a few weeks … I put the tracks in an order where it’s its own kind of story-telling in itself.”

Producer Tony Hiles suggested Scullion include the two songs from the film on the soundtrack. The theme song, ‘Bad Taste’, was written by Mike Minett (who also played Frank in the film and sometimes operated camera) and Dave Hamilton. It was performed by Wellington band The Remnants, made up of Minett and Hamilton, John Derwin, Darcy Crews, Fran Walsh and Scullion herself. The song ‘Rock Lies’ was played by Madlight, and featured vocalist Terry Potter (who played Ozzy in the film and operated camera), John Derwin, Chris Ewers, Steve Hall, and Roger Collinge.

Scullion’s next feature-film score was for Martyn Sanderson’s Flying Fox in a Freedom Tree (1989), based on the novel by New Zealand-based Samoan author Albert Wendt. It was a very special movie for her. “That was shot in Samoa and I was sent there to be part of it. I’m very proud of the score.” Pati “Albert” Umanga (Southside of Bombay), who had played bass for Scullion’s projects for years, also played bass on her moody score. “Pati was also my cultural advisor for when I was selecting Samoan songs for the source music part of the score.”

An 1890s period piece and a 1980s synth

Leon Narbey’s Illustrious Energy (1988) depicts the experiences of two Chinese gold prospectors in Otago in the 1890s. It was scored by composer and pianist, Jan Preston. She says, “It was a very complete and special time for me composing and recording the score to Illustrious Energy. I came over to Auckland from Sydney and stayed in a magical building, an old factory in Herne Bay belonging to a friend of mine. It was a wonderfully creative space. I loved the film (still do), loved working with Leon, and had few interruptions as I hardly knew anyone in Auckland. Plus I was (distantly) in love at the time, I’m not sure if you can hear that in the score!” (Interview with Ryan Smith, July 2022)

Although the film is set in the 1890s, there’s no mistaking Preston’s largely synthesised score was created in the 1980s. “From memory it was a Roland D50,” Preston says. “It was the synth every composer/performer fell in love with after the Yamaha DX7 and they are both iconic keyboards. Composers nowadays listen to film scores and recognise the factory sound from one or other of these machines. Even Hans Zimmer or Thomas Newman scores.”

Because of the subject matter of Illustrious Energy, Preston references the folk music of China through synth textures modelled on traditional Chinese plucked stringed instruments like the pipa or ghuzeng, as well as through her use of pentatonic scales. Her music has a contemporary sound hinting at period music from the era the film is set. “I listened casually to some traditional Chinese music but not too closely. Just enough that a flavour was in my musical subconscious. And the score is very 1980s synth, which strangely works with a (then) contemporary film score sound.”

With racism, extreme weather, opium dens, a circus romance, and the desolate remote rocky Otago landscape, Preston had plenty of dramatic and emotional terrain to navigate musically. “Leon Narbey was wonderful to work with. He briefed me in exactly the way I like to be briefed, like an actor. To know what emotion, energy, atmosphere or story the director wants the music to reinforce. Tell me what the music needs to express, not how to express it musically. That’s my problem to solve.”

As well as synths, some of Preston’s music used an acoustic element. “I recorded Don McGlashan playing percussion live which I think works very well in the score. He came into the studio with a collection of previously discussed instruments and we more or less tried things out on the spot. It was great working with him, and I still hold out hope there’ll be some other film score we can work together on.” At this point McGlashan had already scored a film on his own – the John Laing drama Other Halves (1984).

In 1980, Preston’s band Coup D'Etat had a top ten hit with their song 'Doctor I Like Your Medicine’. She also put her songwriting skills to use in lllustrious Energy, though her end credits song didn’t turn out exactly the way she wanted. “One of the disappointments of this score is that the song at the end ‘To Hear The Ocean’ needed a traditional Chinese (preferably female) voice and we ran out of time to find the right singer, so I sang it myself. Most people like it, but I had a different vision for it, and still feel I’m the wrong singer for that song.”

Preston’s lllustrious Energy score won best music at the 1988 New Zealand Listener Film and Television Awards. It wasn’t her first film score award. Pictures (1981) won best music award at the 1982 Asian Film Festival. “That score is completely acoustic, a string quartet and piano. Me playing with members of the NZSO.” Her prolific output of scores for feature films in the 1980s also included Among the Cinders (1982), Trial Run (1984) as well as scores for documentaries, some directed by Jan’s sister, Gaylene Preston.

A modern medieval odyssey

Vincent Ward originally intended The Navigator (1988) to be an all-New Zealand production, but to help overcome funding problems Australia was brought in to co-produce. Iranian-Australian composer Davood Tabrizi was hired to compose the soundtrack. To score Ward’s unique and surreal medieval vision of the twentieth century, Tabrizi drew on on a large variety of musical styles. These included Celtic music, Scottish military music, Gregorian chants, nineteenth-century mining music, and influences from the Middle East. The Navigator took both best soundtrack and best film at the New Zealand Film and Television Awards. The film was an official selection at Cannes where, after the screening, Ward was given five-minute standing ovation.

Crocodiles’ hippo songs

Peter Jackson described his second feature Meet The Feebles (1989) as “a kind of Roger Rabbit meets Brazil.” The black comedy puppet movie was a satire on musicals and featured a number of songs as well as instrumental music. The score was co-composed by Peter Dasent and Fane Flaws who had previously played together in BLERTA, Spats (with Bruno Lawrence and Tony Backhouse) and the accomplished Wellington band The Crocodiles.

Peter Dasent explains: “Meet The Feebles was my first attempt at writing film music. I was hired because I was also a songwriter and wrote most of the songs with my late friends Fane Flaws and Arthur Baysting in about a week” (Interview with Ryan Smith, June 2022). Baysting, who co-wrote songs with Dasent and Flaws back in The Crocodiles days, co-wrote the lyrics for the Meet The Feebles songs, and his talents as a wordsmith didn’t stop at songwriting. He was a screenwriter too and co-wrote the screenplay for Sleeping Dogs with Ian Mune in 1977. The script for Meet the Feebles was co-written by Fran Walsh, who also contributed lyrics for one of the songs.

In his AudioCulture profile, Dasent describes how some of the songs came about. “They wanted a song called ‘Garden Of Love’, they had the title. And I said to Fane, ‘Garden Of Love’ has got to be a doo-wop song, and so we wrote this doo-wop song. Then there was a group in there called the Funky Black Eels and they wanted a song that Heidi the Hippo would sing with them, so Arthur [Baysting] and I wrote ‘Hot Potato’. And there was one that was Barry the Bulldog’s operatic aria, and I just took an existing tune and put a whole lot of Italian pasta names to it. How did Peter Jackson approve it? I don't know, but he did.”

Nick Bollinger played bass on the Meet the Feebles score along with Jim Lawrie (drums), James Daniel (tenor sax), Graeme Norris (alto sax), Tim Rollinson (guitar) and Peter Dasent (piano and keyboards). The vocals for the singing puppets were provided by Callie Blood, Barbara Griffin (ex-Holidaymakers), Fane Flaws, May Lloyd, Mark Hadlow, and Stuart Devenie.

The songs fed into the incidental music side of the score too. Melodies were lifted straight out of the songs and turned into instrumentals. Dasent says, “The underscore was basically made up in the studio – the sadly missed Broadcasting House studio in Wellington.”

The quirky Meet The Feebles score for was nominated for best score at the 1990 New Zealand Film Awards. And Peter Dasent went on to compose scores for many more films in the 1990s, including Peter Jackson’s Braindead (1992) and Heavenly Creatures (1994).

--

Read more: Film Music Aotearoa, part 1: 1930s-1960s

Read more: Film Music Aotearoa, part 2: The 1970s

Read more: Film Music Aotearoa, part 3: The early 80s

Read more: NZ popular music at the movies, 1964-2014

--

Ryan Smith is a Wellington-based freelance writer and composer whose articles and radio features have largely focused on music, including film scores. By day he produces Sound Lounge for RNZ Concert (a contemporary classical/experimental music show with an emphasis on Aotearoa’s composers and performers) and presents ambient music show, New Music Dreams.

--

Sources

Michelle Scullion, phone interview, June 2022

Peter Dasent, email interview, June 2022

Jan Preston, email interview, July 2022

David Blyth, phone interview, July 2022

New Zealand Film: An Illustrated History, edited by Diane Pivac with Frank Stark and Lawrence McDonald, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2011

New Zealand Film 1912-1996, Helen Martin and Sam Edwards, Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1997

A History of The New Zealand Fiction Feature Film, Bruce Babington, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2007

New Zealand Film Music in Focus, Riette Ferreira, University of Auckland thesis, 2012

Girls’ Own Stories: Australian and New Zealand Women’s Films, Robson & Zalcock, 1997

“John Charles: Musician of Many Parts”, Joy Aberdein, Ritmico, 2011

“Top Dog: Footrot Flats”, Chris Bourke, Rip It Up, January 1987

“Slice of Heaven: The story of Aotearoa’s unofficial anthem”, Yadana Saw, RNZ, 18 December 2021

“Gargoyle Features”, Chris Bourke, NZ Listener, 22 July 1989

“Strata”, Rosemary Hemmings, Art New Zealand, Winter 1982

Thanks to Radio New Zealand Infofind, Ian Pryor of NZ On Screen