By the late 1920s, the silent film era was over. Nearly every movie imported from overseas and shown in Aotearoa had sound and music. And by the mid-1930s, the country was making its own “talkies”, some with their own homegrown soundtracks.

For the next 40 years or so, original soundtracks by New Zealand composers were as scarce as New Zealand films themselves. Only a few independent filmmakers and composers were daring and enterprising enough to create the occasional rare gem during this time. It wasn’t until the end of the 1970s that a vibrant new era in New Zealand films packed previously lukewarm local audiences into cinemas to see their country’s unique stories and hear the music that helped make the films what they are. (With a few exceptions, this overview concentrates on music written specifically for films – scores – rather than pre-existing songs.)

1930s

New Zealand’s first films with sound

On 8 March 1929, a huge Friday night crowd piled into Wellington’s Paramount Theatre to experience the first film with sound (music only) screened in New Zealand: the American film, Street Angel. The theatre was wired for sound just three months earlier and soon others around the country followed suit.

A queue gathers outside the Paramount Theatre, Wellington, waiting for the doors to open for Street Angel - the first presentation in New Zealand of an imminent "miracle - talking, singing, and sound pictures". - Evening Star, 30 March 1929

Now that the possibility of films with dialogue, sound and music was available, films shot in Aotearoa took advantage of the new technology. In fact, four films released in the mid-1930s lay claim to being the first talkie made here (though in 1930 there was a one-minute musical promo clip filmed in Rotorua, featuring Epi Shalfoon’s Melody Makers performing ‘E Puritai Tama E’).

One of the four early talkies was Under the Southern Cross by Universal Studios director, Lew Collins. Shot on White Island, it was originally a silent film but sound was added later in the United States. Bathie Stuart, an actress and singer from Hastings, was visiting California at the time and was asked by Universal Studios to record a prologue for the film. As part of the prologue, she performed a haka and traditional Māori chants. Stuart also assisted with synchronisation of the soundtrack and the film was re-released with sound in the mid-1930s with the new title, The Devil’s Pit.

The original director of Under the Southern Cross/The Devil’s Pit (before being fired) was eccentric American director, Alexander Markey. He went on to direct Hei Tiki (1935), another film that claims to be New Zealand’s first talkie. Hei Tiki also nearly became the first film to have an original soundtrack by a New Zealand composer.

Almost the first New Zealand film score, but not quite ...

Hei Tiki’s United States-sourced budget was large enough to include the building of a thoroughly equipped motion-picture laboratory and theatre on location near Taupo. There was also enough money to commission a score for full orchestra and Australian-New Zealand composer and conductor, Alfred Hill, was hired as the film’s composer. Hill already had an impressive track record, including all kinds of classical music for the concert hall and a hit pop song ‘Waiata Poi’.

Hei Tiki was a romantic drama loosely based on Māori legend and Hill, who had been collecting Māori music since the 1890s, was in part hired due to this interest in Māori culture and music. Hill had previously incorporated (appropriated?) influences from Māori music into his own and wanted to do the same for this score.

Hill was put up in a one-room hut containing a full-sized organ close to where the shoot was taking place. He spent a lot of time among the huge Māori cast in their downtime so that, in his words, “I could get the real atmosphere as well as pick up any stray melodies. I was surprised at the number of gems I obtained from songs used by them during their games. I gained quite a lot of material and two of the best numbers – a farewell song, and a haka accompanying a stick throwing game – I have incorporated in the music for the film” (from John Mansfield Thomson, A Distant Music: The Life And Times Of Alfred Hill).

Hill completed the huge task of writing his score for Hei Tiki and delivered it before returning home to Australia. He planned to return to Aotearoa when it was time to supervise the orchestral recording of his score. The only copy of the written score went back to America with director Alexander Markey but, by bad luck or design, it was subsequently lost. The director replaced Hill with a Los Angeles composer who created a completely new score. Alfred Hill’s score was never recorded, and he went uncredited.

Possibly for the best as it turned out because when Hei Tiki was released in 1935 it was a box-office flop. Any fame, or infamy, it received in America was generally for the nudity it contained.

Hei Tiki wasn’t Hill’s final opportunity to score a film, but in the meantime the credit for the first original music to be recorded and used in a New Zealand film went to someone else.

And the earliest known original music in New Zealand film goes to ...

In an excited report, the Otago Daily Times of 5 November 1934 describes the filming, in Dunedin, of an amateur “talkie” Down on the Farm. A song-and-dance sequence had just been “shot” featuring the comedian J S Dick performing to ‘Down on the Farm (The Rouseabout)’. For this song, and ‘Chicken Feed’, Dick wrote the words, and the music was by dedicated local composer David S Sharp (who wrote ‘How’d You Like to Be Me?’ for the film). According to Fantasy & Folly by Peter Downes and Peter Harcourt, other music was supplied by Sharp and played by Stewart’s Imperial Dance Band and some of the Kaikorai Brass Band. “On that basis it could reasonably be called a musical production.” The film, produced by Dunedin theatre manager Stewart Pitt, was panned by UK critics in 1937: “After this,” wrote the Cine Weekly, “our colonial cousins will be well advised to restrict their exports to mutton.”

As would be expected, an early contributor to a film soundtrack came from an accompanist to silent films. Howard Moody was a cinema pianist in this period, performing with the orchestra at the Crystal Palace Theatre in Cathedral Square, Christchurch.

Howard Moody, 1930. - PapersPast

He was hired, along with lyricist Shaun O’Sullivan, to compose two original songs for the film The Wagon and the Star (1936). It was shot in Southland and Fiordland and directed by New Zealander J J W Pollard. ‘Men of the Road’ and the theme song ‘I’m Gonna Hitch my Wagon to a Star’ were performed by cast members, who were mainly chosen from the Invercargill Operatic Society. The two songs began and ended the film, but The Wagon and the Star contained no instrumental incidental music.

However, Moody’s next film score – Phar Lap’s Son (1936) by American director A.L. Lewis – needed him to compose incidental music in addition to eight songs. Not everyone was enthusiastic about the music when the film was shown in Britain. A Monthly Film Bulletin reviewer called the songs and dances “almost unbelievably amateurish”.

1940s

A remake with sound and music

Back in 1925, pioneering New Zealand director Rudall Hayward had released a silent movie called Rewi’s Last Stand, based on the actions of Rewi Maniapoto and his supporters at the Battle of Ōrākau. Now that the technology was available, Hayward wanted to remake Rewi’s Last Stand with sound and music and began work on this in the late 1930s.

For the remake, released in 1940, Hayward hired Alfred Hill, who returned from Australia to Auckland to begin work on the score. Hill rented a house which he also used as a rehearsal space and worked hard to find the best local musicians. Despite the performers’ low rate of pay, they all put in many hours of rehearsal to get the score’s performance sounding as professional as possible.

Fortunately, this time around Hill’s score was recorded and used in the final film, released in 1940. But not without compromises. A shoestring budget meant a lot of Kiwi ingenuity and improvising was needed to get the dialogue and music soundtrack recorded.

“Hill wrote an elaborate musical score, which unfortunately did not get the full rendering because of very limited facilities,” wrote Virginia Callanan. “It was recorded by Auckland’s 1YA radio technicians in the Avondale Town Hall [now the Hollywood Cinema], which operated as a cinema. The sound recording equipment was hooked up to a belt projector while Hill conducted the musicians.”

The inadequate technical facilities meant the full score was never recorded in its entirety. Many of the musical sequences were also lost in a later version that was destined for England because the film was cut to meet British quota regulations.

After Rewi’s Last Stand was released in 1940, New Zealand-made feature films, and therefore their scores, were incredibly scarce for over a decade.

Douglas Lilburn at home, Wellington. - Cyril Beavis. Ref: PAColl-8656. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Lilburn’s National Film Unit short film scores

However, post-World War II, the state-owned National Film Unit was busy creating short documentaries in the 40s and 50s. And prominent New Zealand composer, Douglas Lilburn – often referred to as the “godfather of New Zealand music” – created four of their scores. These included a chamber orchestra score for Journey for Three (1948), a score for small orchestra for Rhythm and Movement (1948), and music for flute, two clarinets, piano and strings for The First Two Years at School (1950), about philosophies of early-childhood education.

This was a time in Lilburn’s career when he was preoccupied with trying to capture the ambience of the New Zealand environment within his music – an aesthetic he shared with the wider New Zealand arts scene of the time.

The music side of the NFU began to be seen as too expensive and the commissioning of original music was temporarily ceased soon afterwards.

In 1948 two NFU staffers defected to form their own production company, Pacific Films. Between the 1950s and early 1970s, Pacific Films almost single-handedly kept independent filmmaking in Aotearoa alive.

1950s

The only Aotearoa feature film made in the 50s

Director John O’Shea joined Pacific Films to co-direct Broken Barrier (1952) with Roger Mirams. The pioneering inter-racial romantic drama examined cultural complications in a relationship between a Pākehā journalist and a Māori nurse. It was the first New Zealand dramatic feature to be made in the 12 years since 1940 and the only locally made feature film released in the entire decade of the 1950s.

Budget constraints meant the film was made using a voiceover with no dialogue at all, so the right choice of score was critical.

“With Douglas Lilburn’s Aotearoa Overture in mind, O’Shea approached the composer to propose he wrote the crucial element in the completion of the film without dialogue, but Mirams lacked enthusiasm for the idea and made contacts with Terence Vaughan instead.” (Whatever It Takes: Pacific Films and John O’Shea, 1948-2000, John Reid)

Vaughan, a composer and conductor who had made a name for himself in the Kiwi Concert Party, was interested and a deal was made: £50 in advance and £50 from the film’s profits. But not long into writing his score, the National Orchestra of the New Zealand Broadcasting Service (later NZSO) had a crisis and needed a last-minute conductor. The offer was too good for Vaughan to pass up.

The score then fell to Sydney John Kay who was originally brought in to organise the musicians, conduct and supervise the recording. Born Kurt Kaiser in Germany, Sydney John Kay was based in Sydney at the time where post-production work on Broken Barrier was taking place. His German-Jewish jazz group had fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and was in Sydney on tour when the Second World War broke out. He decided to make it his new home and even added “Sydney” to his name in honour of his new city.

Because Broken Barrier had no dialogue, the amount of music needed was huge: 57 minutes and 13 seconds. And budget constraints meant getting it all recorded wasn’t easy. “The recording sessions were a challenge for all concerned,” writes John Reid, “each track could only be recorded in its entirety. As the orchestra played, the music was ‘shot’ live and the soundtrack recorded by exposing a sound negative through a camera.”

1960s

After the release of Broken Barrier in 1952 up until the beginning of the 1970s, only two more feature films were made in Aotearoa, both also by John O’Shea and Pacific Films. There were other independent film companies around, mostly concentrating on commercials and promotional films.

An experimental fusion of image and music

Pacific Films made short films too and, in 1961, O’Shea commissioned director Tony Williams to create the experimental short The Sound of Seeing (1963). Auckland-based avant-garde composer, Robin Maconie, a friend of Williams since high school, provided the music. The score was an eclectic mix of jazz, musique concrète (a style of experimental music that uses recorded sounds as raw material) and experimental modern classical (including the strumming of piano strings). Maconie himself was one of the musicians along with Jane Freed, Jennifer Baigent, Don Mori, Dave Fraser and the Nick Smith Trio (who performed both on-screen and off). Also in 1963, Maconie composed a jazzy score for Williams’s short film Keep Them Waiting.

Filmmaker and writer Roger Horrocks describes the 16-minute collaboration between Williams and Maconie as “unlike anything made in New Zealand up to that time. ‘A Painter’ (Ray Grover, future national archivist and novelist) and ‘A Composer’ (Gary Mutton) were shown wandering the country – simply watching and listening, focusing on things that were seldom noticed, then starting to assemble those sounds and images into edited sequences. The film was a manifesto for New Zealand filmmaking as an art that could ‘enlarge’ both eyes and ears.” (“Twenty Years of Experimental Films”, Art New Zealand)

New Zealand tries its hand at art-house cinema

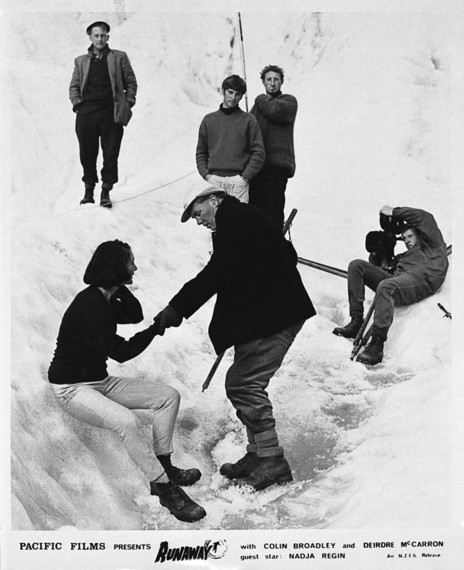

When O’Shea set out to create his next feature film, the dark art-house thriller Runaway (1964), Williams was brought on board as cinematographer, and Maconie composed the score. “According to Maconie, John O’Shea had a keen ear for sound and music and was sensitive to the discreet way in which music can touch and colour visual drama.” (New Zealand Film Music in Focus thesis, Riette Ferreira)

In New Zealand Film: An Illustrated History, Lindsay Shelton says that Runaway’s visually arresting images “combined with the music of Robin Maconie constitute an image-sound sensorium that pushes the basic storyline and themes onto another level.”

At the beginning of the 60s, film festival screenings in New Zealand of European art-house films had a huge impact on local film circles. O’Shea, who was particularly influenced by the films of Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni, created Runaway as a sophisticated attempt to emulate these kinds of films.

As contemporary classical music was often used in European art house films, Maconie, who had immersed himself in the study of European avant-garde art music (later attending courses by, and writing a book about, Karlheinz Stockhausen), was the logical fit.

During post-production of Runaway, Maconie was in Vienna taking a summer course and had to compose the music remotely. A 16mm copy of the pre-final cut never reached him there, which made things even more difficult. Maconie ended up composing the music over five days with just a partial shooting script to work from.

Runaway (1964): Robin Maconie wrote a dramatic solo pipe organ piece for the final sequence. - Pacific Films Collection, Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Throughout the process of composition he worked closely with his friend, cinematographer Tony Williams. Maconie is quoted in Riette Ferreira’s thesis: “I relied on Tony’s exact timing of the individual scenes provided in the shooting script, and the shape and emotional pace of the scenes themselves. Each item of music sets a tone and builds to a climax and then ends abruptly or fades out ... The function of music is to act as a wordless commentary on the scene …”

The music is scored for string quartet, clarinet and piano, and for one section a trumpet, trombone and large gong were added. Solo guitar cues are often used to depict the people of the Hokianga. And the final sequence – where the protagonist David faces his demons and quite possibly death as he trudges alone on a snow-covered mountain – was written for dramatic solo pipe organ. (Some additional music was written by Auckland-based UK composer and conductor Patrick Flynn who, when recording the soundtrack, recruited members of the NZBC Symphony Orchestra, and 20 Auckland jazz musicians.)

• Watch Runaway – complete film at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

The deliberately sparse use of score makes the well-placed music in this film all the more effective. Maconie’s often discordant music compounds the dark atmosphere of the film and reflects David’s troubled inner world.

When it was released, Runaway received a lukewarm response from New Zealand audiences and O’Shea concluded that local audiences were not yet receptive to hearing their own stories. Looking back, it’s easy to see how ahead of its time Runaway was: it’s an unquestionably landmark New Zealand film with a unique score.

New Zealand’s first musical

After Runaway, John O’Shea directed New Zealand’s first full-length musical, Don’t Let It Get You. Most of the music consisted of performances, by Howard Morrison (who co-produced the film), Rim D Paul and the Quin Tikis, Lew Pryme, Eddie Low, Eliza Keil, Paul Walden, Gwynn Owen, and Kiri Te Kanawa. The lively incidental music was by Patrick Flynn who, with screenwriter Joe Musaphia, wrote the spirited ‘Hard Day’s Night’-style title song. HMV released an album of the song recordings, and two pieces by Flynn.

--

Read more: Film Music Aotearoa, part 2: The 1970s

Read more: New Zealand popular music at the movies – 1964 to 2014

--

Ryan Smith is a Wellington-based freelance writer and composer whose articles and radio features have largely focused on music, including film scores. By day he produces Sound Lounge for RNZ Concert (a contemporary classical/experimental music show with an emphasis on Aotearoa’s composers and performers) and presents ambient music show, New Music Dreams.

--

Bibliography

New Zealand Film: An Illustrated History, edited by Diane Pivac with Frank Stark and Lawrence McDonald, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2011.

New Zealand Film 1912-1996, Helen Martin and Sam Edwards, Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1997.

Whatever It Takes: Pacific Films and John O’Shea, 1948-2000, John Reid, Victoria University Press, 2018

New Zealand Film Music in Focus, Riette Ferreira, University of Auckland thesis, 2012.

The Forgotten Soundtrack of Maoriland: Imagining the Nation Through Alfred Hill’s Songs for Rewi’s Last Stand, Melissa Cross, MMus thesis, Te Kōkī – New Zealand School of Music 2015.

A History of The New Zealand Fiction Feature Film, Bruce Babington, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2007.