Bernie Allen has had a remarkably long career in the local music industry, which stretches from playing jazz in clubs and backing Johnny Devlin in the 1950s through to television work that included scoring ‘Hine Hine’ for the Goodnight Kiwi slot on TV2. This conversation took place in 2018 with Gareth Shute as part of AudioCulture’s project to map the Auckland venues of the 50s, 60s, and 70s.

--

I know you started playing saxophone while boarding at Sacred Heart in Ponsonby, but your family home was in Helensville. How did you first become involved in the inner-city music scene?

I moved into Auckland during my first year out of school. I remember talking to one of the guys behind the counter at Begg’s Music Store, when I was buying some reeds. I asked him how to meet other musicians. He said “Oh you go to the Swing Club.” That was a club that used to occur down at the Royal Empire Society rooms in Queen’s Arcade. “Otherwise,” he said, “go to the Radio Theatre on Durham Street on a Saturday night.” You always took your horn because there was always someone looking for someone to do a gig with. Especially at the Radio Theatre, early on a Saturday night.

Then he said “Or you go to blows [jams] and parties. As a matter of fact, there’s a party this weekend, because Shirley Howard over there on the record counter is having her 21st birthday party. Go and ask if you can go.” I said “‘I can’t do that.” He said, “Yeah, you can. Hey Shirley!” So he calls her over and asks on my behalf. Next thing I know I’m ringing up my mate Tony Baker, who was a year behind me at school. I’d asked if I could bring a friend, though they probably thought I meant a girlfriend. So we arrived at this house in Blockhouse Bay, with our horns. That’s where Morrie Fairs the drummer and Shirley lived. All these guys were at the party – Lyall Laurent, Bart Stokes, Billy Farnell – who were the top musicians in the city at the time.

At the end of night, all of the sedate musicians had left and there were just the stragglers and hoons. One of them was a trumpet player named Dave Ironside and he said, “We’re all going down to the Poly, are you coming?” I didn’t know what that was, but we all hopped on the back of this pick-up truck and hooned into town to the Polynesian Club.

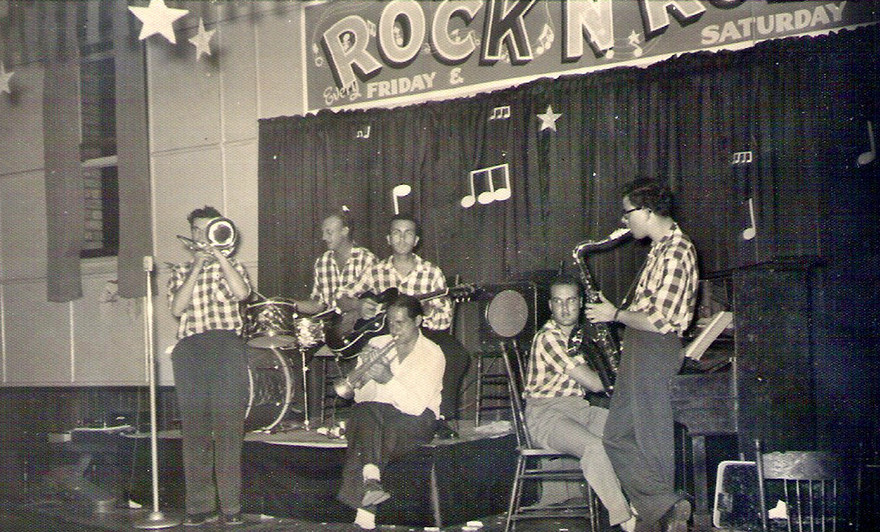

Auckland's pioneering rock'n'roll band, at the Jive Centre, 1957. Among the other musicians are Merv Thomas, trombone, Frank Gibson Sr on drums, Johnny Bradfield, guitar, Bobby Griffiths on trumpet, and Bernie Allen on saxophone. - Merv Thomas Collection

At the Polynesian Club, they had events every Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday. For quite a while that was our main haunt, because if you went earlier in the night then anybody could get up and have a blow with the group. Sometimes there were great guys playing, sometimes they were dreadful. Invariably on the drums was Phil Warren’s partner, Don Williams, who was quite a good drummer. There were guys like the famous [comedian] John Daley, who wasn’t actually a very good trumpet player.

One particular night does stick in my memory. You see, you couldn’t have booze in any of these places. If you went to Peter Pan, you could take a kit bag and you’d have a bottle in there. During the performance you’d put your head down below and take a swig. Usually, the most respectable places got a warning from the cops if they were going to be there, so word would just go around to keep your booze out of sight.

Of course, we were young guys with no money. You couldn’t very often afford booze, so we’d go to Henderson up to the vineyards there and you could buy “Sneaky Pete” or “Purple Death”. It was about four shillings for a 44-gallon drum! If you were playing a less-upmarket place then you’d wrap that in a brown paper bag and keep it in the car, where you’d make frequent excursions.

This particular night we were playing away at the Poly and one of the guys says, “I’m going down for a drink.” He came screaming back over to us and said “We’ve got to get out of here, there’s blood all over the walls, there’s fighting downstairs like you wouldn’t believe.” So we climbed out the window to the awnings of the shops on Karangahape Road and walked along to Prime’s Hardware Merchants and they had a ladder where you could get down most of the way. We were handing the horns down as we went.

There were two American destroyers in town and one of the guys was knifed and killed down there. There were frequently problems like that. Especially if the two boats that serviced the Pacific Islands were in town at the same time – the Kaitoke and the Matua – they were the two island trading boats. Occasionally they were in port at the same time and the crews hated each other. I do remember one case, where the cops came up and lined up the two crews up from the club and marched them back down Pitt Street all the way to the port and then confined them to their boats for the rest of their stay!

So you eventually got to the point where you could play music full-time? Especially once rock’n’roll hit town?

We weren’t exactly making a living. Put it this way: it was regular work. Up until that time, all the dances that everybody played at were reasonably sedate. It was almost like ballroom dancing. At that time, Ted Croad’s big band was playing at Trades Hall [on Hobson Street] but they got fired because they weren’t drawing enough people. I think it was Lee Brassey and Dave Dunningham who put their heads together and decided they could run a dance there [renaming it The Jive Centre], though it wasn’t a rock club as such.

Then Blackboard Jungle came out and the first of the rock’n’roll movies. So one night Frank Gibson Sr and Merv Thomas arrived around at my doorstep and they said “Look, we’re starting up a new band and we’re going into Ted Croad’s old slot, are you interested?” I said yes immediately, because I was only playing two nights a week: I didn’t even ask what it was! Frank said, “The only trouble is we’ve got to play this new music, it’s called rock’n’roll.”

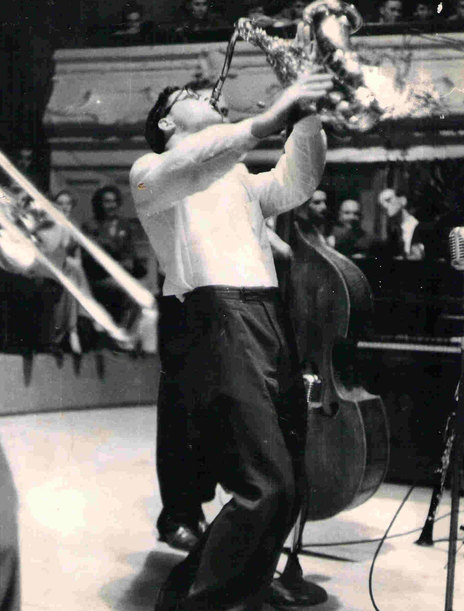

Bernie Allen at The Auckland Town Hall, June 1957 - Bernie Allen collection

At that time, the only records coming into New Zealand were the ones local importers wanted to bring in and you didn’t hear much rock’n’roll on the radio either. So Merv and I used to go to whatever rock’n’roll movies came through town and Merv would transcribe the lyrics while I’d transcribe the licks, then we’d go out and play them! I’m sure Merv got a number of the words wrong and I got a number of the licks wrong, but it worked.

It was full-on how quickly it took off. Next thing you know, another guy called Gill Nichol started running town hall concerts with us. Then Benny Levin got in touch. I knew him as a band leader not an entrepreneur, because he ran the band at the Bayswater Boating Club on Wednesdays nights and then Saturday nights they played at St Seps [in Newton].

Benny teamed up with another musician, Bart Stokes – who was originally from Wellington – and they decided to run a tour with us throughout the country, though Frank didn’t go. It was an absolute sell-out. It was advertised as a line-up of acts, so it depended what shirt you were wearing what band you were in. First you came on as the Merv Thomas’s Dixielanders, then came on as the Bart Stokes Beboppers or the Bernie Allen Rockers. I was billed as being straight from Australia, I hadn’t been there in my life! It cleaned up.

Benny Levin's jazz concert artists tour. Gisborne Photo News No.41, November 14, 1957.

Benny decided that they’d do the same thing again, but Johnny Cooper had got his thing going in Wellington and he decided he wanted part of this action too. They got our itinerary and booked themselves right through the country a week or two before! So it wasn’t quite as successful, though it still made money.

Benny decided that at each town we went to, we’d find a local artist as part of the bill, which was quite interesting. In Wellington we had Rod Derrett [later famous for his musical comedy], then in Rotorua we found a group called the Morrison Brothers [Howard Morrison and his brother Laurie], who also did Gisborne with us. Then, in Palmerston North, Benny was having trouble finding someone, so it was suggested we get this guy from Whanganui, Johnny Devlin, so he rode his motorcycle across to Palmerston North. When we got back to Auckland, Benny then brought Devlin and the Morrisons up to do the clubs around Auckland. Then Phil Warren asked Devlin to record.

You were involved in those early sessions?

I did all 16 of Devlin’s early records. Merv was still at the Jive Centre and he was interested in amateur recording, so Phil got him onboard to do the first recording with Devlin, which was ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ and ‘When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again’. They were recorded down at the Jive Centre and when Phil released them the record did very well.

The other 14 tracks we did up at the Pacific Buildings. The pressing company, Green and Hall, had bought these old studios there: probably in lieu of payment, I don’t know. The studio remained empty most of the time. The Stebbings were just beginning to make a name for themselves at that time – Eldred and Phil. Eldred had his own set-up under his house, but Phil had been recording shows at the Town Hall. He brought in a portable machine at the Green and Hall studios, so we went in there and used that for the Devlin tracks.

Those were recordings were done with the whole band playing live?

Yes. One microphone! We placed people around the studio to get the balance.

You played live with Johnny Devlin as well?

Phil got me to help put the band together. The guitarists who were available mostly didn’t want to play this new genre, rock’n’roll. Then Phil said, “I’ve got a guy working for me who might be able to do it, Bob Paris.” It was a toss-up between him and Gray Bartlett, but we decided Bob Paris was a better fit. Plus, I already knew him – there were three of us musicians who all worked at George Courts at the same time – I was working in display art and Neil McGough was at the Maple Furnishing Company in the other corner doing the same thing, while Bob Paris was doing screenwriting. All around the same time.

But you didn’t go on the national tour with Devlin?

Phil Warren wanted us to go on the road, but I’d decided to get married and didn’t want to do that. Instead, he got a new bunch of younger guys. Well, I say “younger” but we were all pretty young. I’d been out of school a few years, whereas they’d only just left. So they got in musicians like Tony Hopkins, Mike Nock, Peter Bayliss, and Claude Papesch. They toured the country, then Phil took them to Australia, so they did the next set of recordings.

Claude was blind, but he was a hoon – he was a character. I’d known as a school boy, because Claude and Frank Gibson were always on the same bus I took to work. Claude was a dreadful school kid – he’d get on the bus, swearing “fuck!” loudly as he bumped into everything. In those days, that was practically instant dismissal from the human race. We’d sit down the back of the bus and talk music, jazz mainly. When he took over in the Devlin band, Claude had heard about all of the antics I used to get up to, leaping around the stage and playing on my back. He decided he had to be better than that. He’d grab a rope and swing out over the pit! If there’d been an accident, he would’ve destroyed himself completely.

Johnny Devlin and The Devils at Western Springs, Auckland, January 1959 - Devlin, Peter Bazley, Claude Papesch, Keith Graham, and (out of picture) Tony Hopkins

He was a fabulous musician though, both on piano and saxophone. [With Wayne Senior] I did some records later in the late 60s, which were the Sounds of Now records. They had people like Tommy Adderley and Sonny Day copying the latest tracks that were being released in the States, because they took so long to get to New Zealand. Ross Goodwin from Radio Hauraki picked the tracks and he did brilliantly at predicting what would end up at the top of the hit parade.

We had to work really fast – it was like three days to do all the tracks for an LP. So I got Claude in on piano. I’d play the track to Claude and quickly talk through any changes I’d made, then bang – he’d already have it down. I could almost show him something right before we were going to record it and Claude would be on top of it.

What did you do after leaving the Jive Centre and Devlin’s band?

I think that was about the time I’d decided to get married – I’d been too long away from the girlfriend on those previous tours. Then I got the opportunity to join Arthur Skelton’s band, who were moving from Westhaven Cabaret up to the Peter Pan. I’d heard he was adding another sax player, but I couldn’t read sheet music that well. However, I desperately wanted to learn to read so I could make it into the radio band, which was big time. Yet, I still couldn’t at that stage. Fortunately another of the musicians in the band, Bob Taggart, thought I should be the guy to get the gig, so he coached me on the audition pieces.

So you half-memorised them so didn’t have to read them?

Yes! So that’s how I got into Arthur Skelton band. That’s why I left the Jive Centre, to go up there. That was probably the flashest place in town.

You went on to become a school teacher and then worked in television for many decades [his work included running the backing band for C’mon and Happen Inn, then writing soundtracks for TV dramas such as Under The Mountain, Hunter’s Gold and Gather Your Dreams]. However, I wonder how you look back on your role in the birth of rock’n’roll music in New Zealand?

It was just another kind of music to us. It wasn’t the major musical force that it became in later years. To us it was just another gig.