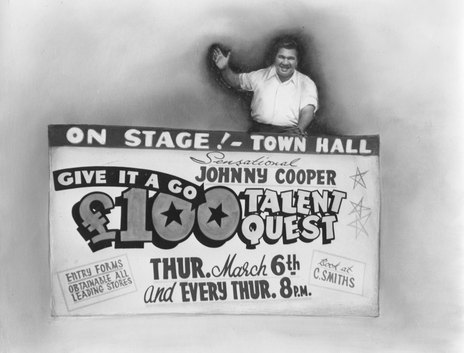

After his brief rock and roll career, he re-invented himself as an entrepreneur, running his talent show Give It a Go! nationwide. Among the talents he nurtured were Johnny Devlin, Mike Nock and Midge Marsden.

His first love was country and western, the genre that gave him his biggest hit, ‘Look What You’ve Done’.

But his first love was country and western, the genre that gave him his biggest hit, ‘Look What You’ve Done’. Thanks to its rhythm and Cooper’s vocal vibrato, the song was given a local flavour, even though he occasionally affected an American twang while on stage.

Released in 1955, ‘Look What You’ve Done’ is songwriting at its most simple, which is probably why it became a sing-along standard in New Zealand soon after its release in 1955. The chorus (“Look what you’ve done, what you’ve done, my baby”) – segues into an equally minimal coda (“I’ve got those lonely, lonely, lonely blues”). Accompanied by an acoustic guitar playing “the Māori strum”, ‘Look What You’ve Done’ was an instant party favourite in an era when men drank from quart bottles and ladies brought a plate. But the song is no period piece: its use 40 years later in Once Were Warriors perfectly captured its timelessness.

Johnny (Tahu) Cooper was born in 1929 and grew up on an isolated farm at Te Reinga in northern Hawke’s Bay. During the Christmas holidays, he would go to the pictures in Wairoa, 30km away, and wallow in the images and songs in Gene Autry movies. “He was a singing cowboy, and I was a cowboy man, brought up riding horses,” Cooper told Gordon Spittle in 1992. Living with his aunt and uncle, he enjoyed listening to artists such as Autry, Tex Morton and Wilf Carter on their wind-up gramophone. He began playing along with a ukulele, and was soon performing in woolsheds, standing on bales while entertaining the shearers.

Cooper, whose iwi was Ngāti Kahungunu, won a scholarship to Te Aute College. After two years boarding there, he won another scholarship, but couldn’t face returning – despite pressure from his family and elders. So he dressed up in his college uniform and got on the train. “I said ‘bye bye’, but in my head I knew I wasn’t getting off that train,” he told Kelly Tikao for RNZ’s Musical Chairs series. “I ended up at the end of the line, which was Wellington.”

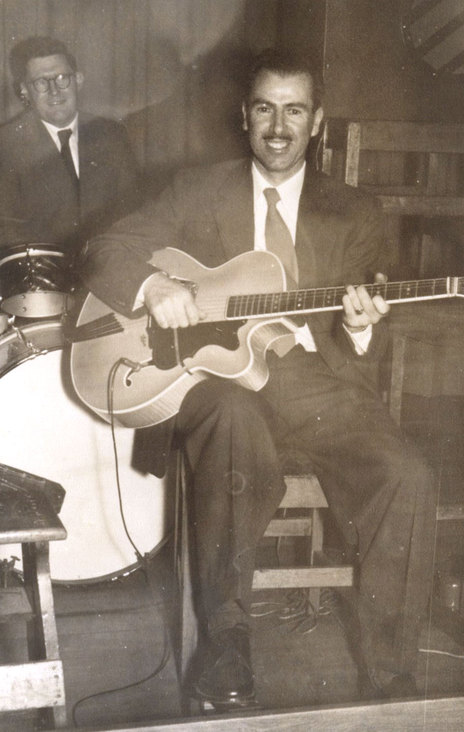

Cooper arrived at the railway station at night, and was impressed by the big buildings he saw in downtown Wellington. He took a room in a boarding house in Karori, and began working as a gravedigger at the nearby cemetery. He used to sing while digging, “and of course the deeper you went, your singing would echo and it sounded good.” He met Will Lloyd-Jones who played slap bass, and a group quickly began to take shape. Ron James was recruited to play piano accordion, and Don Aldridge the steel guitar.

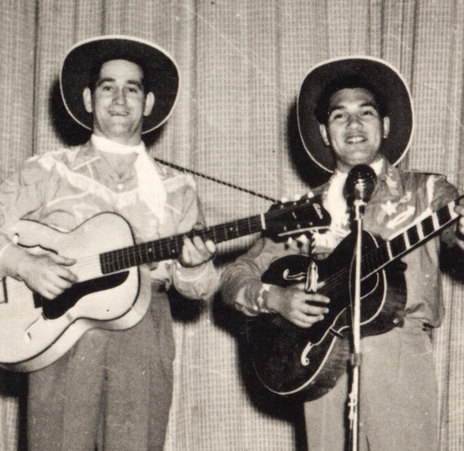

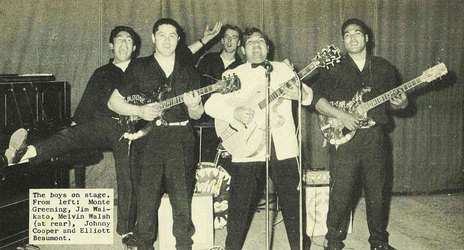

Johnny Cooper and The Range Riders made their own cowboy outfits, bought hats and became regulars at Talent Shows.

Calling themselves Johnny Cooper and The Range Riders, they started entering charity talent shows held in Wellington cinemas on Sunday nights. Their repertoire consisted of country standards by artists such as Autry, Hank Williams and Hank Snow. One night they won £20, and they were soon playing dances at parties locally.

The Range Riders – now joined by Jim Gatfield on guitar and vocals – made their own cowboy outfits, bought hats and neckerchiefs, and became regulars at the Sunday night talent shows. “We could never start before 8.15pm, when everybody got out of church,” Aldridge recalled to Gordon Spittle. The shows were packed, and family friendly. “They had a guy – I don’t know whether he came from Internal Affairs – but he had to stand in the wings and make sure nobody put over any blue jokes or anything. He censored the show … you had to be all prim and proper.”

In November 1950, Cooper made his first recording, at Alan Dunnage’s Sonic studios in Island Bay. Playing his own guitar, he sang the Autry standard ‘Too Late’. The Range Riders later joined him for sessions, recording songs straight to acetate. Among them were Hank Snow’s ‘The Convict and The Rose’, Hank Williams’s ‘Your Cheating Heart’, Tennessee Ernie Ford’s ‘Chew Tobacco Rag’, and the song that became their theme, ‘Ridin’ Along’ (“Ridin’ along, singing a song/ home on the range where I belong”).

The band entered a talent quest at the Paramount theatre, for which the prizes were £20 and an audition with HMV. In the finals, they pipped the favourites – a country comedy act – thanks to the young woman handling the voting papers being sweet on Cooper. HMV had no studios at the time, so for the audition the band set up in the company’s tearoom. "They said, 'Away you go.' So we sang two or three numbers, and they said, “Don’t call us, we’ll call you …' "

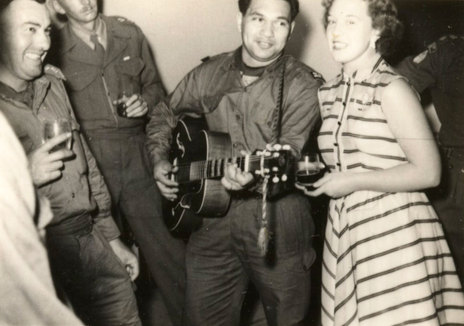

After about a year of badgering phone calls from Cooper – during which he visited Korea as party of a concert party entertaining New Zealand troops – HMV invited the band to do some recordings. Although ‘The Convict and The Rose’ was released first – receiving good radio play – the first song HMV recorded was the Māori pop favourite ‘Manu Rere’. Several more followed in the first few months of 1955, including ‘Sippin’ Soda’ (with a chorus from Wellington Girls’ High) and Sam Freedman’s ‘Haere Mai’.

Cooper’s original, ‘Look What You’ve Done’ Was heard in shearing sheds – every party you went to in the late FIFties

The breakthrough came with ‘One By One,’ a hit ballad for Kitty Wells that suited Cooper’s croon; on the B-side was Cooper’s original, ‘Look What You’ve Done.’ After its success in New Zealand, it was recorded by several others, including Wilf Carter and Slim Dusty. Ironically, when Cooper demoed the song, HMV thought he was joking: they thought it was too repetitive. With its simple “lonely blues” chorus, the hardest part was getting HMV to release the song.

“I tell you what, the words were hard to write,” Cooper joked to Tikao. “There were about six words in the whole song – good, eh? Look what you’ve done and lonely blues. That’s why it became a party song – you didn’t have to learn the words.”

On the A-side was ‘One By One’ a duet with Margaret Francis; the double-sided hit eventually sold 80,000 copies. "Wherever we went, in shearing sheds or anywhere – every party you went to in that period – that’s all you heard them play," recalled Cooper. The Range Riders played wherever they were welcome: in woolsheds after the shearing was cut out, at dances, at charity shows as far afield as Waiouru and Wanganui, and on 2YC’s Radio Trail.

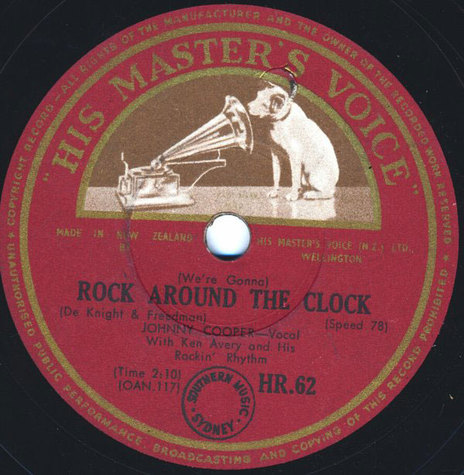

Surprised by the sales, HMV’s A&R man Dave Van Weede offered Cooper a five-year contract. HMV released five 78s in the first half of 1955 before Van Weede invited Cooper in to discuss a record in a new genre. It had been a big hit in the States; it was called ‘Rock Around the Clock’.

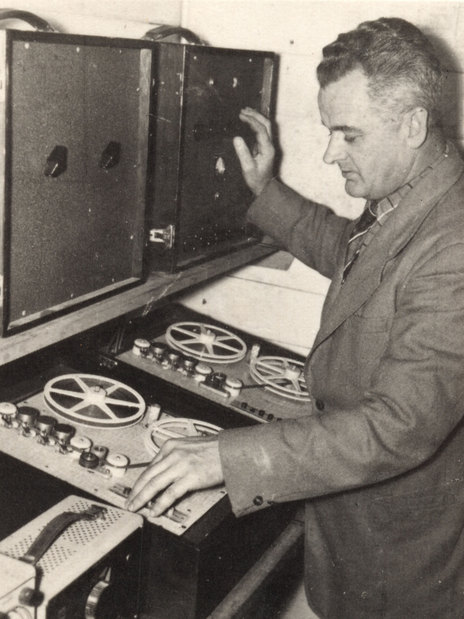

Reluctance and confusion were Cooper’s first reactions when he was asked to record Bill Haley’s hit. The words made no sense, and neither did the beat. “I sang love songs. It was foreign.” But HMV’s man insisted, and Cooper was under contract. On Saturday 27 August 1955, Cooper and a group of Wellington jazz and dance band musicians assembled at Alan Dunnage’s recording studio at 223 Clyde Street, Island Bay. On saxophone was Ken Avery, Vern Clare played drums, Doug Brewer double bass, and Bob Barcham the piano. As Don Aldridge didn’t like rock and roll, the guitarist was Jimmy Carter (in 1948 he had played lap steel on Pixie Williams’ version of ‘Blue Smoke’).

Avery recalled the session: “We set the thing in the key of G to suit Johnny and recorded it almost note for note from the Bill Haley disc, except that I asked Vern Clare to put a sustaining drum beat near the end where Haley’s band cuts out completely. For the B-side we recorded ‘Blackberry Boogie’. It’s interesting to note that HMV sent no representative to supervise that recording. It was all left to Alan Dunnage.

“Late on Saturday night, Alan rang to say that HMV liked the ‘Rock Around the Clock’ number, but couldn’t accept ‘Blackberry Boogie’ because it had a ‘popping’ sound in the parts where Johnny sang ‘blackberry pickin’ time.’ Could we re-record the ‘Boogie’ side early on Sunday morning so Johnny could catch the afternoon plane? A bleary-eyed group turned up and remade the ‘Blackberry Boogie’ side as requested and all was well. We received three guineas each.”

His recording of ‘Rock Around the Clock’ was released in New Zealand before Bill Haley’s version.

Cooper caught his plane, which was to take him on his second tour of duty to Korea. But his recording of ‘Rock Around the Clock’ was released in New Zealand before Bill Haley’s version. Van Weede’s press release read, “Johnny Cooper – Mr ‘One By One’ – has converted to rock’n’roll.” On the radio pop show the Lever Hit Parade, Selwyn Toogood introduced the song as “a new sound from America, done by our local boys”.

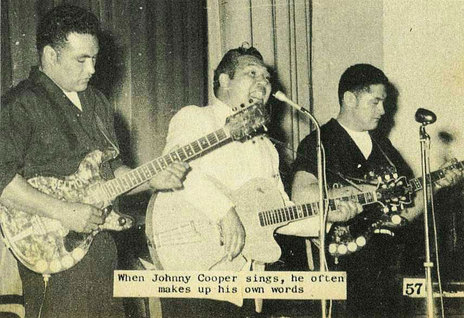

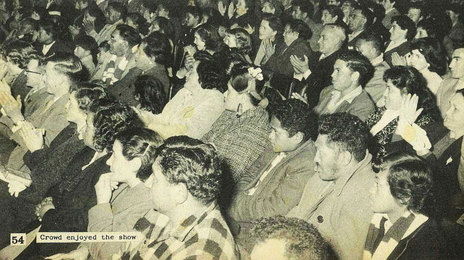

Soon, Haley’s version and its prominence in the film Blackboard Jungle eclipsed Cooper’s recording, but he was now required to perform rock and roll at his shows. In December 1955 he was invited by musician and entrepreneur Don Richardson to appear at one of the regular Jazz Festival concerts at Wellington’s Town Hall. The big band jazz musicians sat back while a small combo accompanied Cooper as he jived and sang, “One two three o’clock, four o’clock rock ...” Saxophonist Lawrie Lewis recalled, “That’s all we heard. The crowd went mad, they absolutely shrieked ... From then on, for the rest of the concert the crowd just didn’t want to know about anything else.” At half-time, the jazz musicians conferred among themselves, saying, “My god, we’re finished: what happens now?”

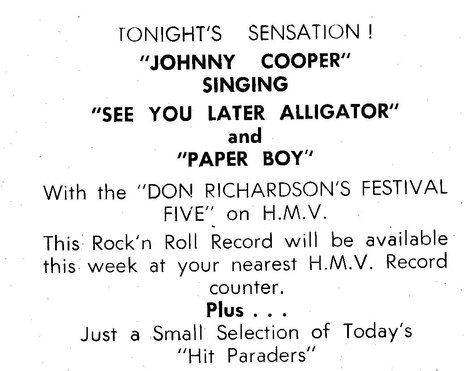

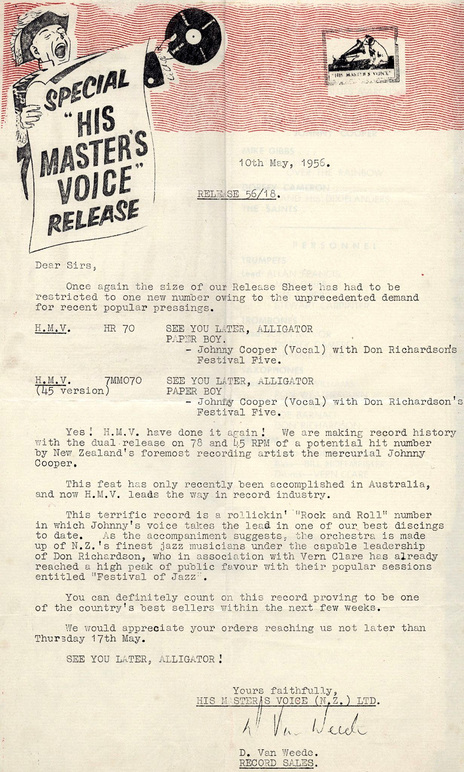

In early 1956, HMV released its first local album, Rock and Sing With Johnny Cooper, a 10-inch compilation of his earlier country and pop recordings, plus ‘Rock Around the Clock’ and ‘Blackberry Boogie’. As a follow up to his rock and roll debut, the company chose the most obvious song: Bill Haley’s other big hit, ‘See You Later Alligator’. For the session, Van Weede re-hired the musicians from ‘Rock Around the Clock,’ with Don Richardson replacing Ken Avery on saxophone.

Calling themselves Don Richardson’s Festival Five, they assembled at the Majestic Cabaret one evening it was closed, and Van Weede laid on some beer to get the musicians in the mood. Roping in several bystanders and the engineer, Van Weede led the chorus shout of “See you later, alligator … after a while crocodile …”

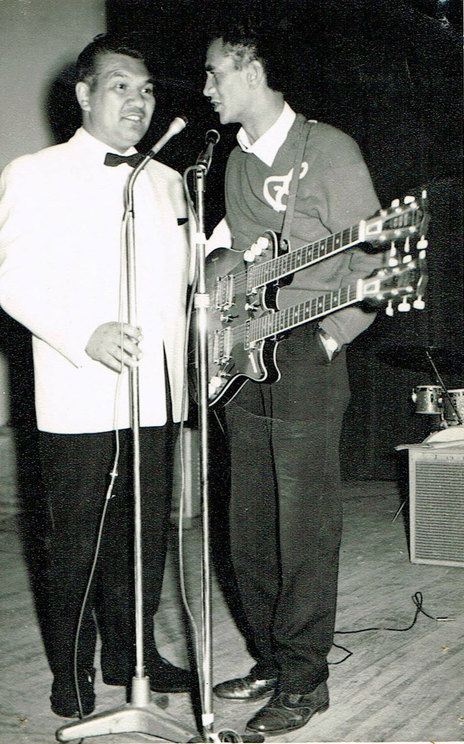

Cooper’s version of ‘See You Later Alligator’ was released on 10 May 1956, on 78rpm and 45rpm discs. Four days later, thanks to his regular radio play and stage work, Cooper had a starring role at Richardson’s sixth Festival of Jazz. Backed by Richardson’s big-band arrangements, “He threw himself into his four numbers with vitality and had the audience behind him from the first bar,” wrote one reviewer. After ‘See You Later Alligator’ and ‘Seventeen’, the audience called out ,"'Rock Around the Clock', Johnny," and so he sang it; everybody sang it, and he was just one of the chorus.”

By the end of the year, the act topping the bill at the jazz festivals in Wellington was Johnny Cooper. Lewis knew something was up when a rehearsal took half as long as usual: instead of 20 numbers, the big band only practised 10. "I thought, this is weird, there is nowhere near a concert here …"

On the night, Wellington Town Hall was packed as usual – 2,300 people – but applause for the first few items was merely polite. After the big band and Dixie items, a drum kit was placed in front of the jazz musicians. “Don went out the front of the stage, none of us knew what the heck was going on. He said, ‘Ladies and gentleman, the special guest, Johnny Cooper.’ Johnny Cooper? Never heard of him. And a Māori with a white jacket and carnation comes on, with a guitar around his neck. He sort of looks around and he says, ‘One two three o’clock …’ That’s all we heard. The crowd went mad, they absolutely shrieked.”

The Dominion enthused, Cooper was as Fine a showman wellington had seen in some years

By now, the critics were as sold on Cooper as the audience. The Dominion enthused: “Cooper was as fine a showman as Wellington has seen in some years, throwing everything into ‘Razzle Dazzle’, ‘Rock Rock Rock’ and ‘See You Later Alligator’. This last was too much … they simply had to dance and the gallery walls were soon a fringe of leaping figures.”

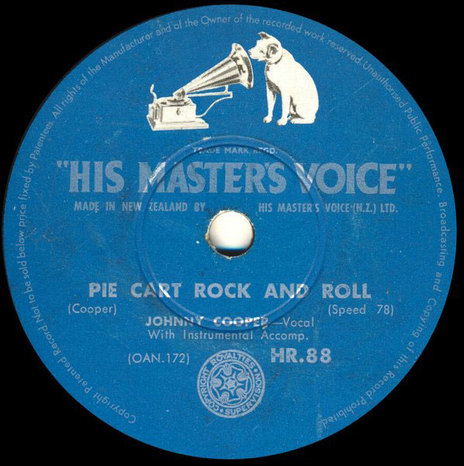

In 1957 Cooper recorded another original, regarded as the first New Zealand-written rock and roll song to be released: ‘Pie Cart Rock and Roll’. Cooper and his band went often to Wanganui to play at charity shows at the opera house. Afterwards, they would go to the local pie cart for some “pea, pie and pud”. Cooper claimed that he said to the owner of the cart, “If I write a song about the pie cart, do you think we could get free feeds?” The owner agreed (although decades later his wife ruined the story by saying that it was untrue). That night Cooper sat down and wrote a song that was standard-issue rockabilly given a Kiwiana twist:

Rock to the rhythm of the pea, pie and pud

Jump to the rhythm of the pea, pie and pud

I got the pie cart rock’n’roll my baby

The pie cart rock’n’roll my baby

The pie cart rock, the pie cart rock’n’roll …

Once again, HMV was dubious: a song about a pie cart? And for a single? But they agreed to record it, and used a mobile unit in a building near the Wellington railway station. Jimmy Carter played the solos on his Spanish acoustic guitar, Don Richardson was on sax, and Will Lloyd-Jones on bass.

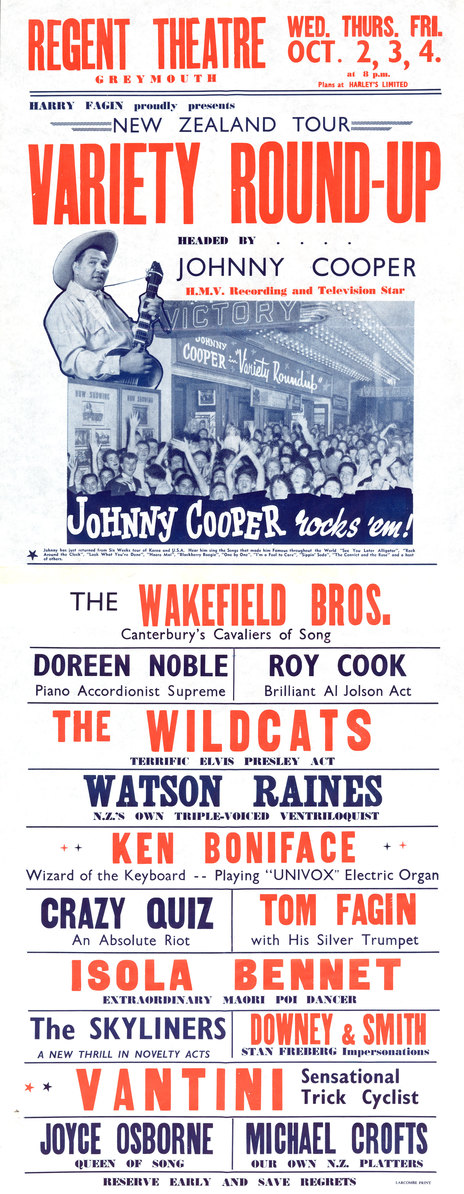

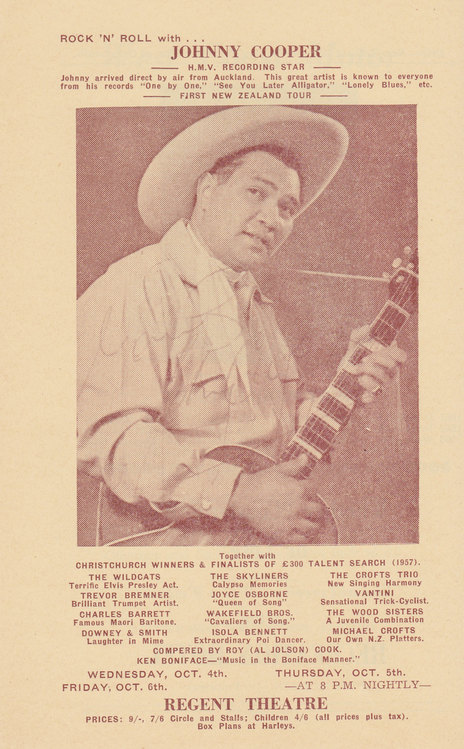

Despite the headlines that rock and roll generated, Johnny Cooper and other acts needed to keep their audiences broad. Two years after recording ‘Rock Around the Clock’ he was top of the bill in a variety show in Greymouth. The October 1957 show was a reflection of contemporary entertainment: as well as teenagers in winkle-pickers, the show needed to appeal to families, country and western fans, and the elderly. So, alongside Cooper and the Wildcats (“a terrific Elvis Presley act”) were a female accordion virtuoso, an Al Jolson imitator, a trick cyclist, a poi dancer and many other acts.

Variety shows would be his future, and for a decade from the late 1950s he organised Give It a Go! talent quests throughout the North Island.

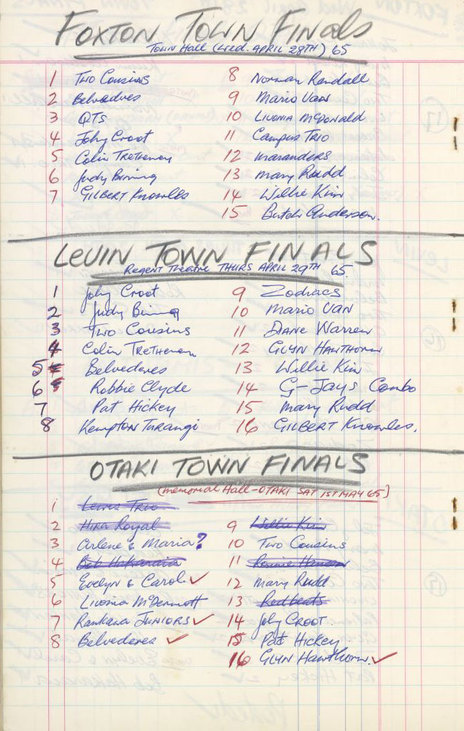

Cooper didn’t forget the importance of rock and roll to his audience, and he never neglected country music, his first love. However variety shows would be his future, and for a decade from the late 1950s, he organised Give It a Go! talent quests throughout the North Island. Among the musicians who appeared in them – either as contestants or backing musicians – were future jazz star Mike Nock, balladeer John Rowles, bluesman Midge Marsden and country-pop star Maria Dallas.

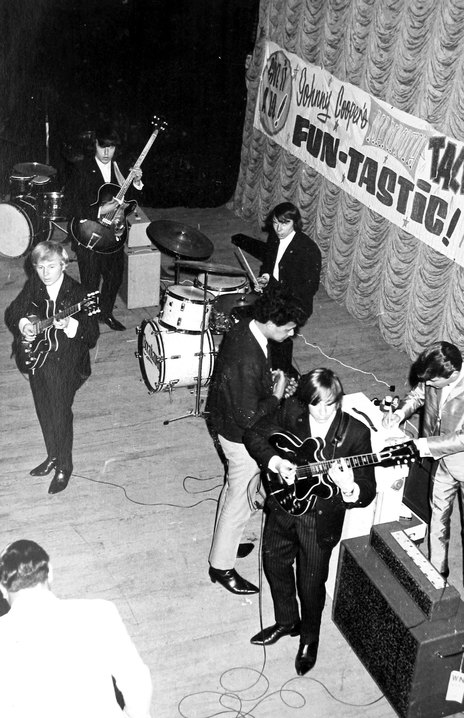

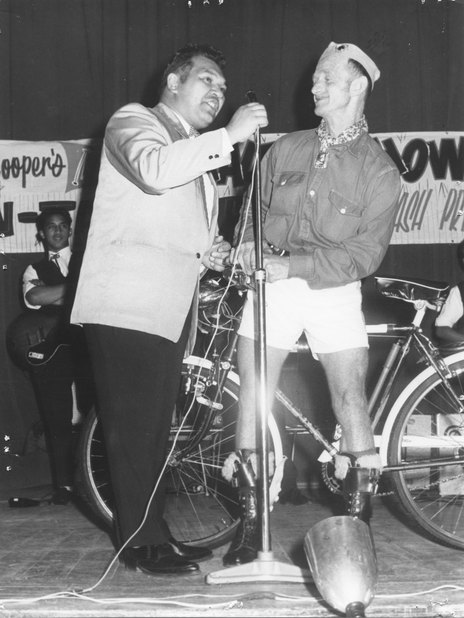

The Give It a Go! shows were a provincial phenomenon, as successful as Selwyn Toogood’s It’s In the Bag quiz show; they evolved into other talent quests run by Cooper, such as Lucky Strike Talent Quest, Johnny Cooper’s £100 Talent Quest, The Mammoth £200 Cashway to the Stars Talent Show, and Battle of the Sounds. Some nights these shows seemed to attract everybody from the surrounding district to a local hall. Cooper would either take his own band to back the acts, or hire a local band.

As a promoter, Cooper knew all the tricks. In 2006 Nock told me that as a teenager in Cooper’s travelling band he had to be a jack-of-all-trades: “I was playing ragtime piano just to open the show, I was also the ticket collector in disguise, plus the pianist for the singers and all whatever … yet we used to carry our own winners with us. It was this trio of Māori girls from the Taranaki district. So everywhere we went, this totally self-contained unit would come to town: a big talent quest, with big prizes. But of course, no prizes were ever awarded – that was my connection with Johnny Cooper!”

Nock recalled that one time, the ring-ins didn’t win: “We had to not win, because it was the mayor’s son or something who was obviously the winner. He was so excited, he thought he was going to get a brand new bike. I think the prize was something like 10 shillings – that’s all we can afford! We had to get out of town real fast …”

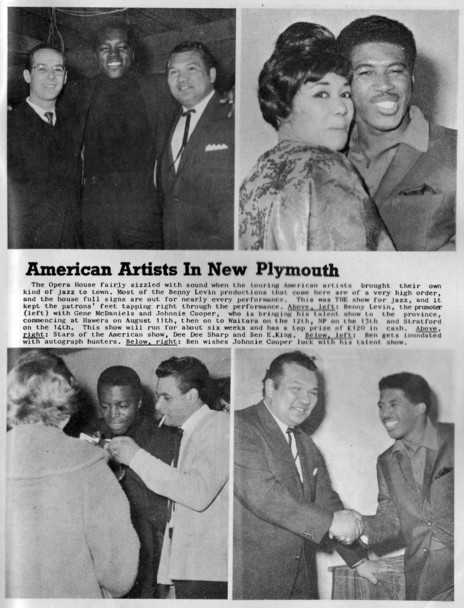

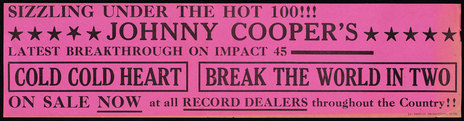

But Cooper’s talent quests and variety shows came to an end around 1967. They faced competition from television – albeit a single channel – and the change in licensing laws that allowed pubs to stay open until 10pm. The pubs also offered resident bands or talent quests of their own. In 1968, a decade after his heyday, Cooper’s last recording to be released came out on Benny Levin’s Impact label: ‘Break the World in Two’ b/w ‘Cold Cold Heart’.

Cooper kept playing, the Johnny Cooper Sound in the 1970s to perform at weddings, parties, anything, several nights a week. “We had to know all the songs,” he told Tikao. “We played country music as well, but you had to cover the whole lot.”

In the 1980s, Cooper played drums and sang in the Wairarapa-based Original Ruamahanga River Band. Gordon Spittle wrote, “They play 21st birthdays, race days, rodeos and sports evenings, singing numbers like ‘The Green Grass of Home’ and ‘Ten Guitars’. They are no cowboys but a line-up that Cooper calls a social band.”

John Dix’s Stranded in Paradise (first published in December 1988) introduced a younger generation of rock fans to the role Cooper had played in founding rock and roll in New Zealand.

Spittle grew up listening to Cooper’s early classics in the 1950s and interviewed him for Music in New Zealand in 1992. Cooper talked of his plans to record with some contemporaries from the 1950s: singers such as Pixie Williams and Margaret Francis. He was working on an original song for the album – he had written about a dozen since ‘Look What You’ve Done’ – and he said he was trying to keep it simple. “Three chords with a catchy tune – shearing shed stuff.”

Johnny Cooper was 85 when he died at home in Naenae, on 3 September 2014. He was a pioneer in many areas of New Zealand music: country, pop, rock and roll, songwriting and promotion. A loveable rogue.

On 22 October 2020 it was announced that Johnny Cooper was inducted into the The New Zealand Music Hall of Fame.