On April 30, 2025, Adam Holt stepped down as chairman and managing director of Universal Music New Zealand. He had been the head of the company since 2001, 24 years, making Adam the longest-serving head of a major record company in New Zealand, ever. (The formal arrival of the record industry in New Zealand was 99 years ago, on 21 March 1926, the date that His Master’s Voice (NZ) Ltd – later called EMI – was registered in Wellington.)

Who loves who the most? Jordan Luck and Adam Holt. - Adam Holt Collection

For those 24 years, Universal wasn’t just a record company. It was the most dominant record company the country had seen since the original era of HMV’s dominance passed in the mid-1970s. A decade into his tenure, Universal acquired the remnants of the HMV/EMI company, having earlier also taken over PolyGram, which had previously absorbed Pye, Tanza, RCA’s New Zealand catalogue, Allied International, Philips, Vertigo, Mercury, and Polydor.

With the exception of Viking, Kiwi, Zodiac, and Impact, in 2025 Universal Music owns nearly the entire catalogue of locally recorded music prior to the arrival of WEA and CBS in New Zealand in the mid-1970s. During Adam Holt’s years in the local record industry, it moved from what had been essentially a service industry, selling mainly US and UK acts to New Zealanders, to an industry that sold our music to the world, a shift that Adam was central to, both before and during his years at Universal.

His personal history as “a record man” takes in – take a breath – Lorde, Sol3 Mio, OMC, Pitch Black, Elemeno P, The Exponents, Dawn Raid, Hayley Westenra, Gin Wigmore, Zed, Nesian Mystik, The Bleeders, Dei Hamo, Kog, Six60, Round Trip Mars, Rob Ruha, House Of Downtown, Cut Off Your Hands, Concord Dawn, Fast Crew, The Naked And Famous, deryk, Shapeshifter, Hinewehi Mohi, The Phoenix Foundation, Ruby Frost, Beastwars, Adeaze, Ratbag, and a massive reissue campaign of New Zealand’s musical past.

It also takes in the advent of streaming: the most significant change in how music has been delivered to the end user since Thomas Edison first introduced his cylinders into the marketplace in 1877. It was a change that nearly destroyed the record industry as we know it.

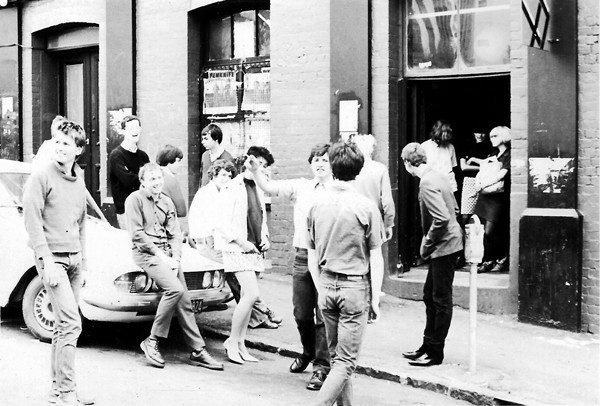

Assorted Screaming Meemees, Ainsworths and Killjoys outside XS Café, late 1980. Adam Holt is on the left, and in the centre, pointing, is Hilary Hunt. Adam’s future wife, Lisa Richards, is standing in the doorway on the left. - Photo by Anthony Phelps

I first met Adam at two events. The first was at the long-demolished XS Café on Airedale Street, a venue that served as the inner-city nerve centre for an influx of bands from the schools and halls of Auckland’s North Shore. I had fallen in love with a quartet who were part of that scene, partly due to the enthusiasm of their engaging manager, Hilary Hunt. I had seen The Screaming Meemees several times before, but Hils was keen to get as many bands as possible from the scene onto an album of new bands I was putting together, soon to be titled Class of 81. With that in mind, he invited me to a showcase at XS, headlined by the Meemees. When I arrived, Hils called me over and asked me to handle his band’s sound as he was going to be on stage. I protested that I had never done sound before, but agreed when I saw that the “desk” only had half a dozen sliders. The band was The Ainsworths, and afterwards, the guitarist from the band – a young fella with a big blond quiff – told me I had done well. That was Adam.

The next time we met was when Hilary and Adam brought a tape into the record shop where I was working. It featured three tracks by The Ainsworths recorded at Harlequin Studios during the midnight to dawn deals. Their track ‘Danger Man’ was included on Class of 81.

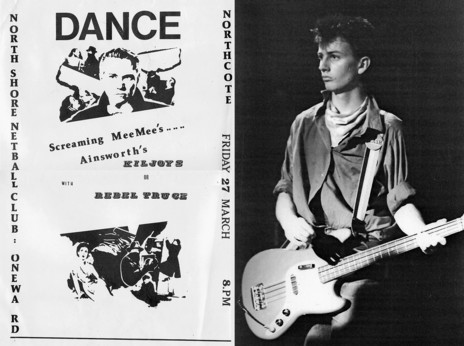

Four band bill at the North Shore Netball Club, 27 March 1981; Adam Holt at XS Café, 1981, photo by Anthony Phelps

Adam Holt was born in the UK but raised on Auckland’s North Shore. His secondary school was Rosmini College in Takapuna, the same school that Hilary and the four Screaming Meemees attended. It is one of Auckland’s great musical schools, one that seemed to nurture talent time and time again during those punk and post-punk days when the population of Auckland’s North Shore was expanding rapidly and there was exciting new music seemingly everywhere.

“Our school band was called The Contents,” says Adam. “A guy named Rod Alley was the singer in our band, and he knew how to build guitars. His dad owned all the woodworking tools necessary. He was building a guitar for me, and I needed some pickups. I’d heard around the schoolyard that this guy, Michael O’Neill, had some for sale, so I hit him up at lunchtime and formed a friendship that basically changed my life.”

Adam grew up with music: “A Hard Day’s Night, I would have been about five when I first heard it, and to this day it’s still my favourite Beatles record. There’s something about those short songs; ‘If I Fell’ is something like two minutes and 20 seconds, and it’s the most perfect song; just intro/verse/chorus/bridge/reprise. It’s just brilliant. I just loved that record. Then growing up with my older brother [Damian], Sweet and Slade were massive, which obviously led to Bowie and Roxy Music. I also went through a rock phase with Rory Gallagher, Kiss and a bit of Deep Purple, before falling in love with Thin Lizzy and Eddie & The Hotrods, who were the perfect bridge for me between rock and punk.”

Like many of his generation, the arrival of punk in New Zealand upended everything.

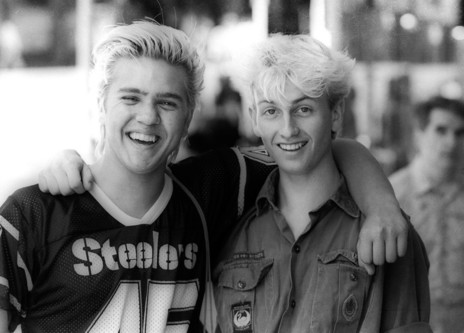

Michael O'Neill of the Screaming Meemees with Adam Holt

“Damian came home with Never Mind The Bollocks, and I just went, wow! I missed the first wave of punk; I was in the second wave. The Clash and Buzzcocks were the two bands that stayed with me. They changed the way I listened to music, and that led to making music. I had been listening to Deep Purple with Ritchie Blackmore, thinking it was amazing, but that I could never play it. Then I heard Steve Diggle with the Buzzcocks, and thought, ‘Oh, that’s a two-note lead break, I can do that’. I never did it particularly well, but I was able to do that.”

Meeting Michael O’Neill also broadened Adam’s musical horizons locally. Michael was the guitarist with The Screaming Meemees, the hottest band in the emerging North Shore dance hall scene, and his extended family and friends would become central to Adam’s world. It was through the O’Neill family that Adam met Lisa, who would later become his wife. The Contents supported the Meemees at the 1979 school fair. Through them, Adam hooked up with possibly the key figure in the scene, Hilary Hunt, another Rosmini pupil who was managing the Meemees and had just begun booking halls around the North Shore, pulling other bands from other local schools into the scene.

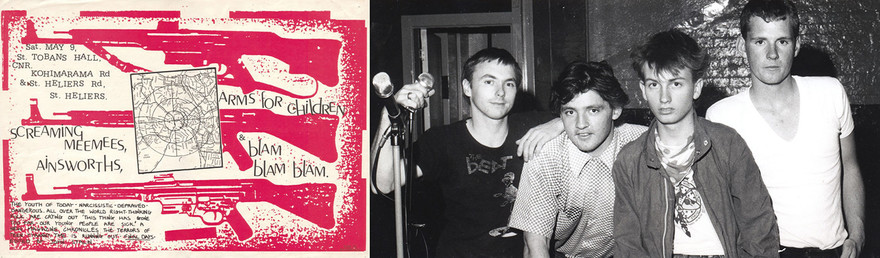

The Ainsworths share a bill with the Screaming Meemees, Blam Blam Blam, and Arms for Children, 1981. The Ainsworths (L-R): Rowan Sheddon, Hilary Hunt, Adam Holt, Phil Jackson. - Photo by Murray Cammick

Adam joined Hilary as the guitarist and then the bassist in The Ainsworths in 1980. Originally an eight-piece, the lineup had settled down to Adam, Hilary (vocals), Rowan Shedden (guitar), and Phil Jackson (drums) by the time the band made its foray across the bridge. The Ainsworths were led by Hilary as scene-meister to the halls and underage venues in the city, one of which was XS Café.

There’s a well-known photo of the North Shore kids on the wall across from XS, taken by Anthony Phelps on 13 December 1980. Adam is in the centre, sitting between Mike O’Neill and Rowan Shedden. Hilary stands above to the right, cigarette in hand, pondering what he had created.

"North Shore Invasion": the Sunday News was the first to use the phrase, when publishing this photo of bands posing across the road from XS Café, on Airedale Street, 13 December 1980. Adam Holt is seated second from right, with Michael O'Neill beside him. - Anthony Phelps

“We were really lucky to have Hilary, who was just so driven,” Adam tells me. “I never knew then how I ended up recording in Harlequin or playing at the show; it was just Hilary hustling. He was out making all the connections with you, with Bryan Staff [XS co-owner], and Doug Rogers [Harlequin Studios], getting all those midnight-to-dawn recording deals. You just get lucky when you meet amazing people who push things. Hilary was that.”

Class of 81 (Propeller, 1981) - Design by Terence Hogan.

Hilary placed The Ainsworths on the Class Of 81 collection I was about to release, and by early 1981, their track ‘Danger Man’ was all over University of Auckland radio station Radio B (now bFM). It was a bona fide student radio hit and part of the city’s soundtrack that summer. The band played the launch party at Mainstreet, and their set was broadcast live on B.

They followed that with one side of a double A-side single (with The Regulators) on Hilary’s one-off Olympic Records label, but the band split soon afterwards.

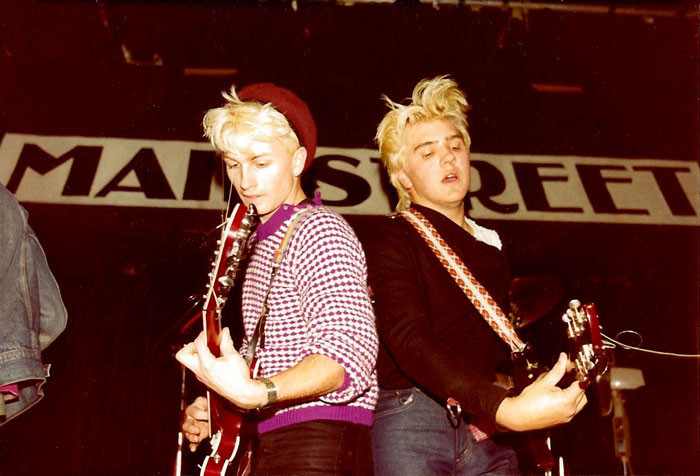

Adam’s friendship with The Screaming Meemees often had him on stage with his mates, playing second guitar, uncredited, apart from an onstage credit from singer Tony Drumm. In another of the era’s iconic images, Adam and Mike are standing on the stage at Mainstreet with the Meemees. It’s an image of two close friends in an unspoken musical bond. I can still hear this picture.

Adam Holt (left) playing with The Screaming Meemees' Mike O'Neill, Mainstreet, Auckland, 1982

“There was just this energy about this group of people in the scene,” says Adam. “It was quite intoxicating. That’s where it started. I loved music but I wasn’t allowed to leave school until I got a job. After failing sixth form, I got my first job working in a bank, and I spent every cent I earned on records. I bought record after record and was obsessed with music; I just loved it all. Hanging with the Meemees was amazing because through them I started to see the machinations of industry and came to realise that you could actually put out records yourself, not just buy them. Then the Meemees had a number one single [‘See Me Go’, 1981], and you go, wow, this is amazing. They were such a great band. They really knew how to take something and move it forward; they constantly evolved, and we always followed them.”

The music industry was already calling. It was the new age of indie labels. Everyone joined a band and, naturally, made records simply because they believed that was the logical next step. There was an excitement about creating and selling our music that New Zealand hadn’t witnessed for many years. An attitudinal sea change.

“Propeller [Records] was a real inspiration. Seeing you work, Simon, showed me that you do it because you’re passionate. You just do it; you don’t really think about it.”

Adam Holt (in Travelodge uniform), Carolyn O’Neill and Charlotte Dawson, outside Mecca Café, Queen Street, 1982. - Adam Holt Collection

Adam’s path into the industry was circuitous, though. “It was 1983, I had left the bank, was on the dole and short of cash. Hilary was working at the Travelodge downtown and said he could get me a job there. I told him I wouldn’t go back to work unless I can earn this much, and, of course, he gets me a job earning twice that. And I went, ‘Oh, okay, that’s quite good.’ And then for a year or so I worked as a night auditor, starting at 11pm and finishing at about 7 or 8 in the morning.”

Down the road was the then-current hot club, Quays, where Adam and all his friends spent their weekends. “If I was working on a Saturday night, Quays was just down the road, and so at three in the morning everyone would come out of Quays, bowl up to the Travelodge reception to see me and I’d be in there with my crimplene suit and my combed-down blond hair … all these drunk people from Quays, my friends …”

Nevertheless, that job eventually led Adam Holt into the music industry. When his night shift at the Travelodge finished at 7am, he would always be “the first customer in the EMI Shop Downtown, usually around 9 am. Roger Liddle [the manager, later of Marbecks and Southbound Records] was there. One day, he said, ‘Oh, are you free at lunchtime? I’ve got no cover. Could you come in and help out?’ I did, and I was offered a job."

Liddle recalls, “He would come into the shop pretty much every morning, so I got to talking with him and learned he played the guitar and was joining a band [Sons In Jeopardy]. One day, he came in a little downcast, saying he wasn’t enjoying his job. I said my assistant hadn’t come into work that day, and I was a bit stretched – would he like to help out?”

At the EMI Shop Downtown in 1985: Geoff Dunn, Roger Liddle (centre), manager of the store, and Adam Holt - Roger Liddle Collection

It was early 1984. “He was a natural,” says Liddle. “I contacted the head office in Wellington and said I’d like to employ another staffer … [I also] employed Geoff Dunn and James Williams. We were the supreme team and felt we had all bases covered.”

The EMI Shop in Downtown was part of a chain of 16 stores nationwide. Under Roger’s leadership, this team quickly became the group’s No.1 branch.

Adam: “It was the best education. I loved music, but I was very narrow in my tastes. I knew what I knew, and I liked what I liked, but it was Roger who put me onto soul and country music – onto Bruce Springsteen, Dylan and much more. He taught me so much. It was amazing, and I still, to this day, think it was the best job I ever had because you’re obsessed with music, and then people come into your shop, and you do your best to turn them onto it. Roger was great, and I owe him a lot.”

Roger: “Adam had his hair all gelled up in those days, and the stream of girls through the shop was quite something.”

Adam worked at EMI for about two years but was then poached by Robin Lambert at Sounds Unlimited, at 75 Queen Street. Sounds was the shop of the moment. As the nation’s import restrictions were lifted in the early 80s, Lambert began to fill the bins with weekly imports of new releases, from the UK especially, bringing current post-punk, indie, and alternative releases to customers within days of their UK release. The allure of these new releases, along with better pay, made the offer hard to resist. Working in the record shops funded Adam’s passion for the bands he was playing in.

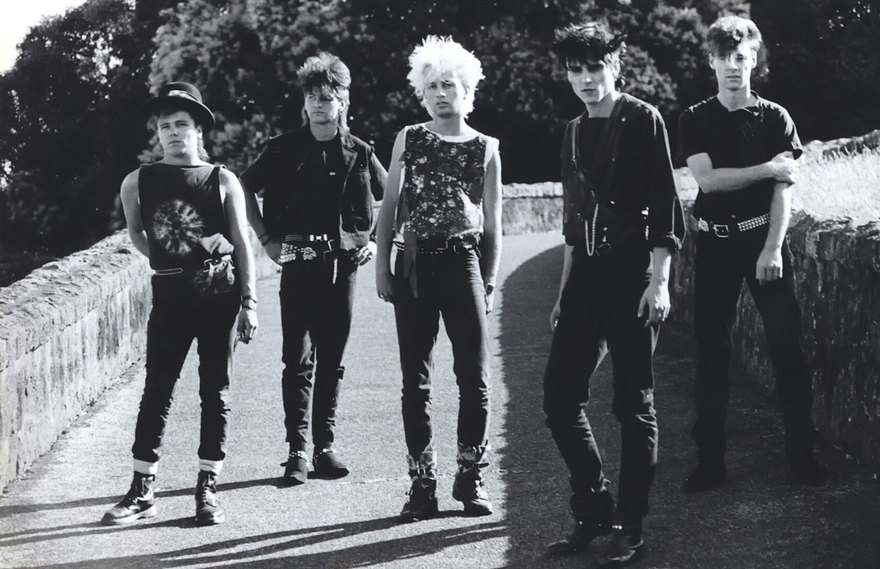

Sons In Jeopardy (L-R): Paul Cairns, Wayne Flintham, Adam Holt, Andrew Bishop, Paul Masja. - Murray Cammick Collection

In February 1984, Rip It Up rumours noted that Adam had joined post-punk, big-haired goth-rockers around town, Sons In Jeopardy, as a guitarist. The band had formed in mid-1983, and Adam was too late to appear on their debut 45, ‘Ritual’, released in January on manager Don Tennet’s Rootbeat label, but he was in time to promote the band, which had a growing presence in the Auckland live scene. They released a second single, ‘Sign Of Life’, in July on John Doe’s Hit Singles label, but neither bothered the charts or commercial radio.

Sons In Jeopardy’s Andrew Bishop has written a brief history of the band for AudioCulture here.

A national tour was promised, but by June 1985, Adam was noted again in Rip It Up as a member of Hip At The Cathedral, playing at the Six Month Club with former Screaming Meemees vocalist Tony Drumm and Sons In Jeopardy bandmates Paul Majsa and Wayne “Wattie” Flintham. They became Shades of Hawaii and eventually, by December, The Rollmops. Adam, Rip It Up incorrectly reports, was also recording solo tracks at Jed Town’s Fetus Studio.

The final Adam-in-a-band notice was in July 1986, when RIU told us he had formed a new band with two other Screaming Meemees, Peter van der Fluit, Mike O’Neill, and Michael “Harry” Harallambi from the Dance Exponents.

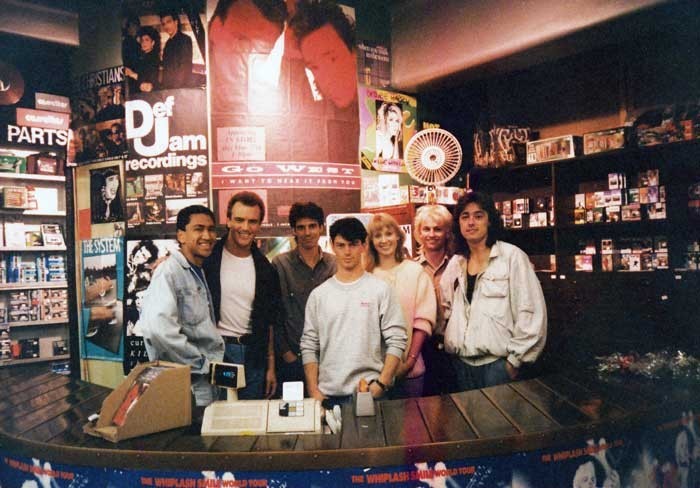

256 Records in 1987 after a Go West in-store: Left to right is Mike Haru (256 staff, later Mai FM) Peter Cox (Go West) Robin Lambert (Sounds Head Office) Geoff Wright (later DJ Presha), Michelle (256 Records) Adam Holt, and Richard Drummie (Go West) - Adam Holt collection

By 1986, Adam had become the store manager at the Sounds-owned 256 Records on Queen Street. In early 1988, restless about his career prospects, he briefly moved to Michael O’Neill’s fashion label, The Cutter of Newton. Realising the clothing industry was not for him, he took a job at The Record Warehouse – then in its final days – and while working there, he was offered a position at Festival Records doing promo. It was a side of the industry he’d long wanted to get into.

“I realised that although I could play the guitar, I wasn’t great. I couldn’t sing and I couldn’t write [songs], so I was always reliant on someone else’s talent. I thought, I’ve got to take charge of my own thing. I loved the record-shop work but was intrigued by the record company reps coming in, thinking, ‘Oh, that looks like a really good job.’ I started putting out feelers to see if I could get a job [in a record company].

“[Festival Records’] Simon Baeyertz came in one day and said he was looking for a promo person, and I jumped at the chance. I’m grateful to Simon because finally that was my entry into a record company.”

Festival Records staff with Toni Childs, 1989. From left: Kim Sokolich, managing director Jerry Wise, Adam Holt, John Gough, and Sandi Riches - Adam Holt Collection

At that time, Festival was headed by the late Jerry Wise, a giant of a man, both physically and professionally. Jerry used his position at what was then one of the most important record labels in Australasia to support local music, often going far beyond the call of duty to provide financial and promotional support for the many independent labels that Festival distributed.

“Jerry was just an absolute legend and a real inspiration. There are key people I’ve met throughout my life, and Jerry was one. He was a big English accountant who used his position of power to help people, and that really had a lasting effect on me. He was always saying things like ‘We need to look after Murray …’ (Cammick, whose Southside and Wildside labels were via Festival) or whoever it was.”

After Simon Baeyertz moved to Mushroom in Australia, Adam was basically running day-to-day promotions at Festival Records. Looking back, he suggests it wasn’t his finest moment professionally.

“I was a terrible promo person. I had no idea what I was doing. I thought that my job was to champion every record that came in. It’s probably a bad record company secret, but you can’t make everything work. It was the late Ross Goodwin [ex-Hauraki, then 89FM] who said to me, “Adam, you can’t tell me everything’s good. Tell me what your priority is”. He told me to weed things out a little bit and chase things that I thought would work. But yeah, I wasn’t great at promo. I didn’t love it and it wasn’t really my strength.

“Towards the end of 1989, PolyGram bought Island Records and, shortly after, A&M Records [both key labels distributed by Festival Records]. The boss at PolyGram, Grenville Turner, rang me and asked me if I wanted to come over and do promo there. I said that I didn’t want to do promo, so he offered me a label manager’s position. And I said, ‘Oh, yeah, that’d be great, I’ll take it, but what’s a label manager?’ I didn’t have any idea what a label manager was at that point. We didn’t have them at Festival.”

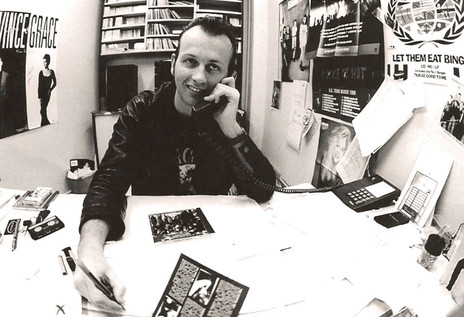

Adam Holt at PolyGram, 110 Mt Eden Road, Auckland, 1990. - Adam Holt Collection

Adam admits he struggled for the first six months, trying to “figure it out”. However, working in what was then one of the biggest record companies on the planet allowed him to start understanding the intricacies of international business, something that a promo job at Festival didn’t easily offer up.

It may have been a large global record company but, locally, PolyGram had experienced a mixed decade, particularly with the New Zealand catalogue. It started the 1980s strongly with releases that included Graham Brazier’s classic Inside Out album and others by his fellow ex-Hello Sailor writers, Harry Lyon (Coup D’Etat) and Dave McArtney (The Pink Flamingos).

However, a change in management to a new Australian boss, Nigel Sandiford, resulted in PolyGram dropping of all local acts. The focus shifted entirely to the international catalogue, such as Dire Straits. All New Zealand records were deleted, and between 1982 and 1988, the record company signed no New Zealand artists, concentrating instead on international releases and the new CD format.

Sandiford was replaced in 1988 by Grenville Turner, from Queensland. Overnight, things changed. “He knew that to be a real record company, you had to have local, and he’d signed a couple of acts and was open for more.”

Christchurch band Dance Exponents had experienced highs and lows over the past six years. Their debut album, Prayers Be Answered, released in 1983, became one of the best-selling local albums of the decade. However, the follow-ups, Expectations (1985) and Amplifier (1986), performed less well, with the latter receiving poor critical reviews (ironically, 40 years on, both are now far better regarded). The band’s core decided to try their luck in the UK and were now in London, where they were pulling substantial crowds and wrote and recorded demos. They were generating interest from major record companies but it sadly led to nothing. Enter the newly appointed PolyGram NZ label manager – who also happened to be a mate.

Adam Holt settles in at PolyGram NZ, 1990. - Adam Holt Collection

Adam: “PolyGram had a school for young execs, and I was sent there. It was in the Netherlands, and I had to go via the UK. While there, I visited [Exponents bassist] Dave Gent. I caught up with him in Barnes, across the road from Olympic Studios and asked what he’d been doing. He said, ‘Oh, we’ve been recording. We’ve got the band together again; we played a few shows and all that …’ Then he put on a tape, and it was the demo of ‘Why Does Love (Do This To Me)’. It was amazing!”

The demo included three more songs, and Gent handed it to Adam, who put it into his Walkman the next day and listened to it repeatedly over the following days as he travelled back to Auckland. “And I just knew that these were hits.”

Adam had never done A&R before and had never signed an act, but “I just knew ...”

He picked his moment, approached Grenville Turner, and asked if PolyGram could sign the band. Turner requested to hear some songs, so Adam played him ‘Why Does Love ...’, and his boss said, “That sounds pretty good, let’s do it.”

The Exponents signing to PolyGram in 1990. From left: Rodney Hewson (PolyGram), Adam Holt, Michael Harallambi, Grenville Turner, Jordan Luck, Brian Jones and Dave Gent - Adam Holt Collection

There was some scepticism in the industry when the signing was announced, not least because others saw The Exponents as a spent force. (They had dropped the “Dance” prefix and briefly flirted with the name Amplifier, in a move that predated Shihad’s Pacifier blunder by some years.)

Adam Holt thought – instinctively, knew – otherwise and had the support of a large record company that was keen to re-establish itself as a major player in the local recording industry.

Read The Exponents and Adam Holt. “He may have thought we could be dicks at times, and he’d be right”

The Exponents’ return to New Zealand, the recording of the album that would become the multi-platinum Something Beginning With C, and the string of smash hits – not least ‘Why Does Love ...’, our alternative national anthem – is well documented. However, perhaps the most important lesson drawn from the pathway to that record was that it relied not only on the skills and, especially, the songs of the band, but also on the instincts of Adam and his belief in both. He understood this lesson, and it provided a future template that would repeatedly change the musical landscape, both in Aotearoa and, eventually, worldwide.

--

Read Adam Holt, part two: OMC and ‘How Bizarre’, Universal Music NZ, digital challenges, Hayley Westenra, Dawn Raid, Elemeno P, Gin Wigmore, Lorde, Sol3 Mio …