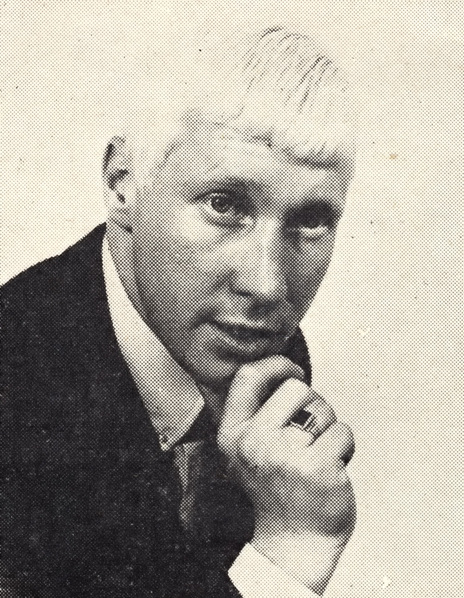

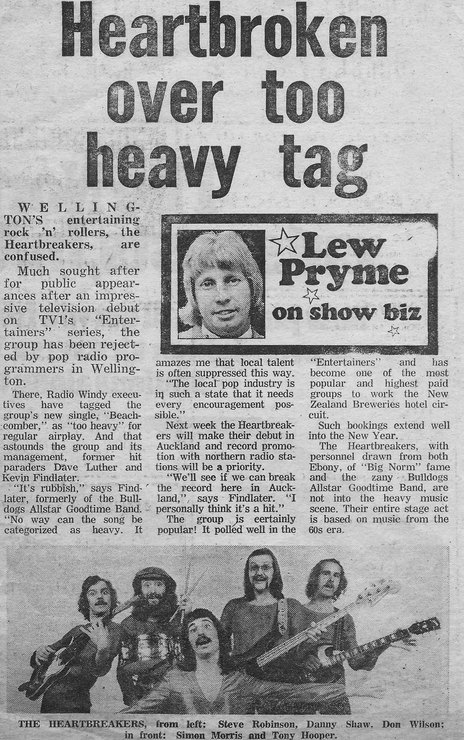

Lew Pryme may not be much known these days – he died of Aids-related illness in 1990 – but his life was quite remarkable. His career was not without some surprising music-related controversy, and – unusually for pop stars of the period – he felt a keen sense of civic responsibility.

In 1965 at age 22, he ran for a seat on the Auckland City Council on the Labour ticket and made clear he was serious. As a former journalist he knew his way around civic affairs and said he wanted improvements to sports facilities and the Auckland Public Library, which at the time was inadequate, dark and pokey: “[It] can be compared with the Black Hole of Calcutta.”

He also envisioned a new civic centre – 25 years before the Aotea Centre opened – and campaigned to get youth engaged in local body politics. Young people should take part in civic affairs as form of insurance, he said: “We are the ones who benefit from improvements in the long run.”

Pryme was also critical of the city’s inefficient public transport. “There are too many small bus services,” he told the New Zealand Herald. “It would be better if these could amalgamate to form fewer but larger companies. As things are now, many men prefer to travel to work in their own cars and this, of course, creates parking problems.”

That was a pop star – who lost out by the slimmest of margins, just 57 votes – more than half a century ago on Auckland’s traffic woes.

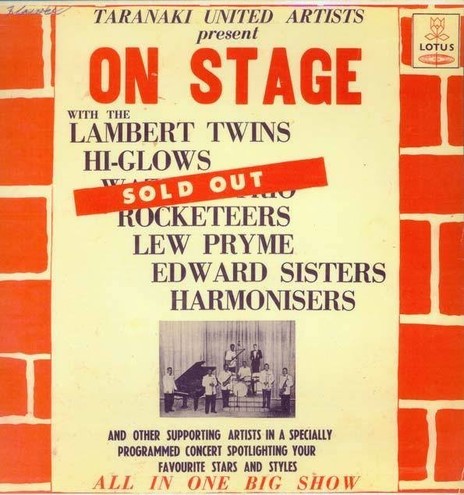

Lew Pryme was born in Waitara, Taranaki (population 1500 at the time) into a family of five brothers and a sister. He entered his first talent quest at six, played drums in his older brother’s skiffle group and joined the New Plymouth band the Nitelights alongside Dave Orams and Bari Gordon, later to be in Bari and the Breakaways with Midge Marsden.

With his good looks, impeccable manners and confidence he quickly became the vocalist at the fashionable Monaco.

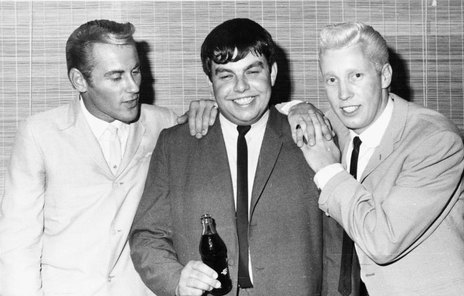

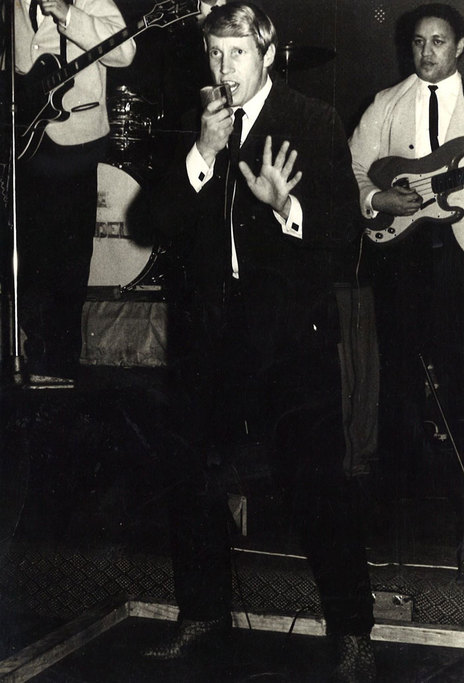

He performed on Johnny Cooper’s pop-package tours alongside Big Jim McNaught and Tommy Adderley and then – after a period as local reporter – headed to Auckland in 1963 where he worked for the Truth newspaper and sang on the dance circuit.

With his good looks, impeccable manners and confidence he quickly became the compère and resident vocalist at the fashionable Monaco. The following year he signed a five-year contract in Wellington with the Octagon label.

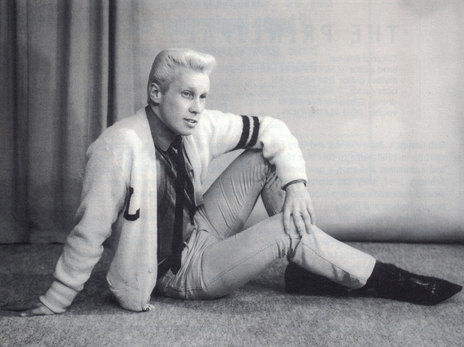

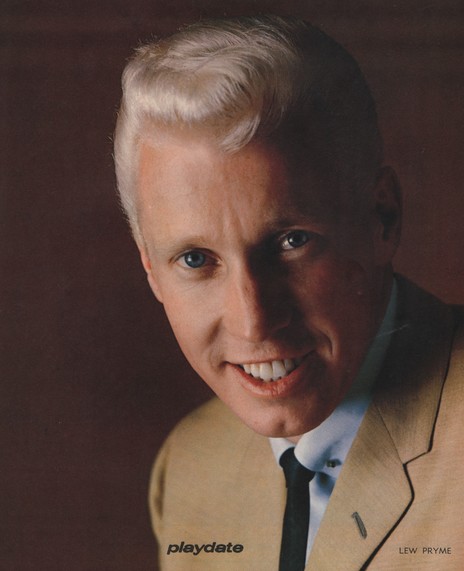

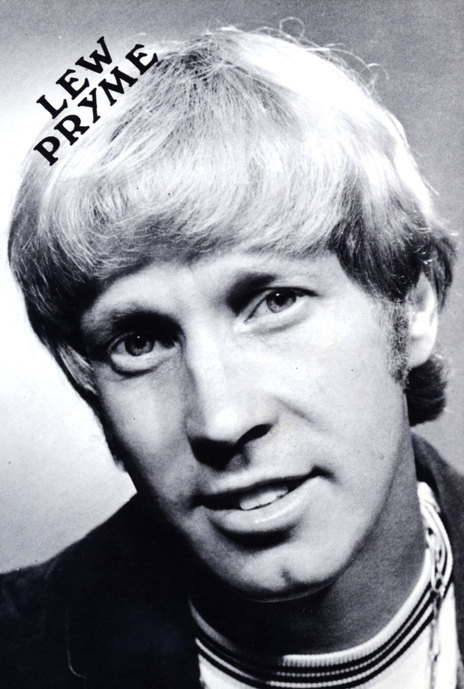

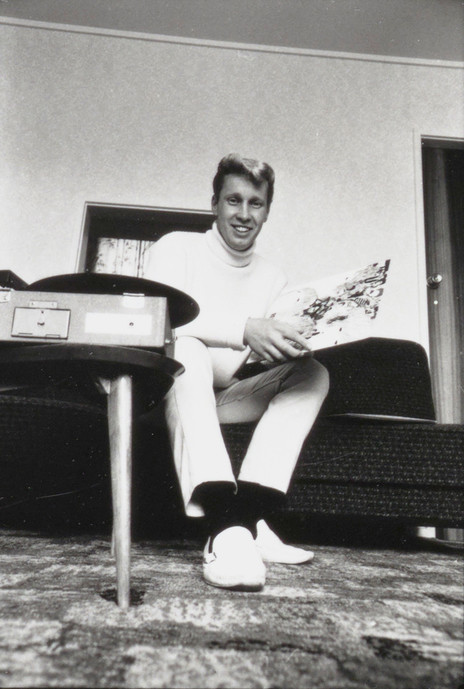

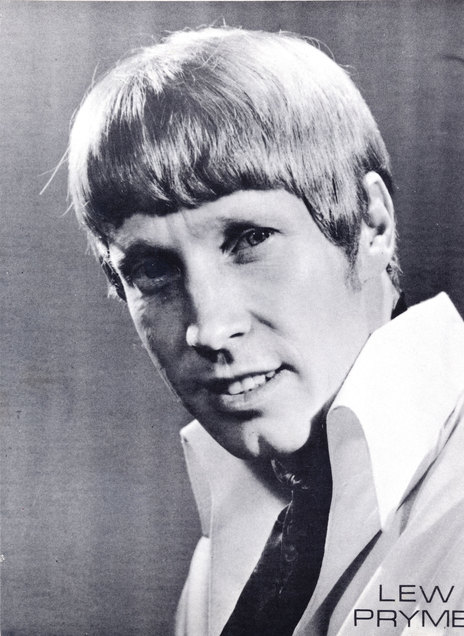

His hairstyle made him unmissable in the brief news items about his career which regularly appeared in the Auckland papers. He re-tinted it silver-blond every 10 days, he told the NZ Herald. “I'm not ashamed of the fact that my hair is my gimmick,” he said. “If people ask me about it – I tell them.”

By early 1965 he already had four singles released – his debut ‘Pride And Joy’ reaching the top five on the Lever Hit Parade – and when The Crystal Palace Ballroom re-opened in April 1965 Pryme was there alongside the Sierras band. At the end of that year played the juvenile lead as a peasant boy in the Christmas pantomime Babes in Toyland.

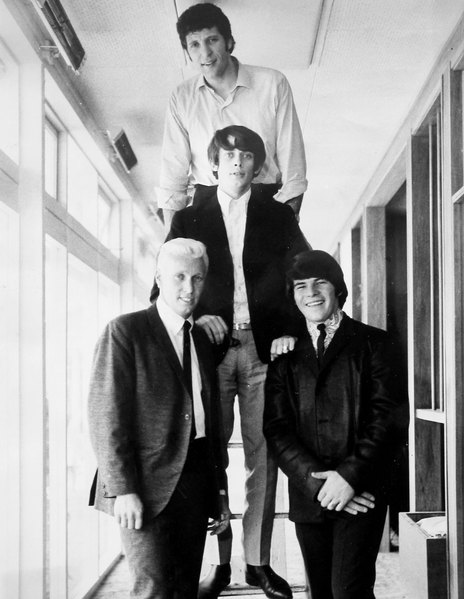

Looking back at just the two-year period when he was at a particular peak after that debut single, it is interesting how he moved effortlessly between the world of teenage pop and mainstream theatre. He opened for the Dave Clark Five in 1965 and Herman’s Hermits the following year, yet also did panto, played in more adult clubs and appeared on the television pop shows Let’s Go and C’mon.

Yet, despite his busy career, he also played second five-eight in the varsity fourth-grade side every Saturday when he wasn’t touring.

Always athletic – he won races at school, worked out with barbells, had a lifelong passion for rugby – in mid-1965 Pryme was quoted in a small Auckland Star item saying the cover of his impending debut album would feature him wearing his varsity rugby kit. With his active sporting life, this was no gimmick, wrote the paper. The album title would be First Fifteen. (Despite extensive research, it cannot be confirmed the album was ever releeased.)

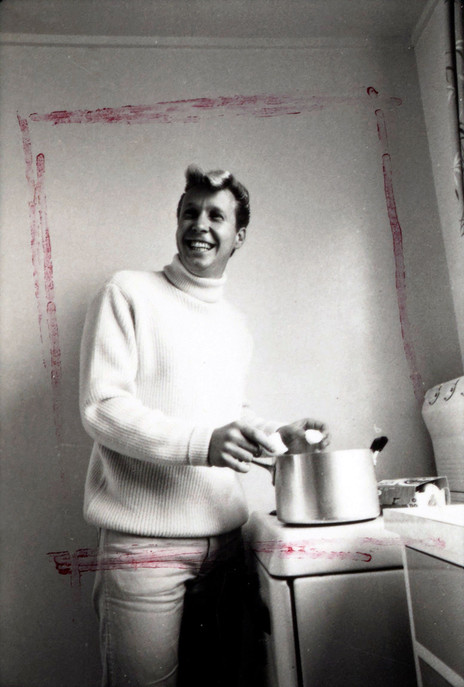

He toured and recorded constantly, played clubs like the Top Twenty, and then came his cameo in Don’t Let It Get You – in one hilarious sequence, he performs in the back of an open-topped sports car as a large black blowfly stubbornly clings to his silver-white hair. It seemed as if he was unstoppable.

He had mainstream pop appeal as a schism was appearing between pop and rock, and drugs like marijuana and LSD were making in-roads into the public consciousness.

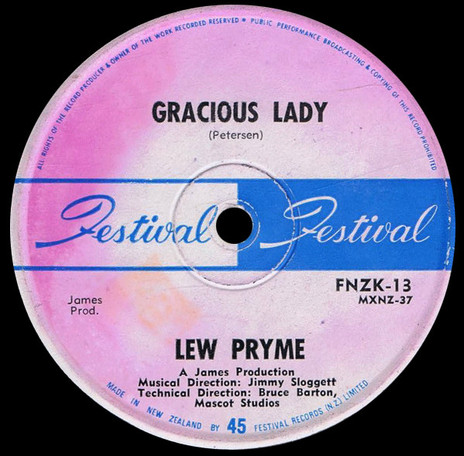

Although he appeared to be on the side of conservative and responsible citizens, he became embroiled in a controversy in 1968 – the same year as he appeared in another pantomime, The Old Woman Who Lived in the Shoe at His Majesty’s Theatre in Auckland – when he recorded ‘Gracious Lady (Alice Dee)’.

It was written about an LSD trip – the clanging hint is in the title – by the House of Nimrod’s Bryce Petersen.

As music writer Andrew Schmidt notes, “I doubt anyone compiling a list of New Zealand pop singers most likely to become embroiled in a drug scandal in 1968 would have rated pop vocalist Lew Pryme in their top 100. Pop pickers thought Pryme played for the other team where drugs were concerned. But there he was, having to explain away the best song of his career.”

Radio i banned the song, but not before they played it once by mistake and raised the ire of a Herald reader who, under the pseudonym “Social Worker”, complained that the record was “about the joys and pleasures of taking a very dangerous drug … when taken without medical supervision.”

The station’s managing director, Mrs B M L Thomas, was reported as saying that the orchestration was not bad but the lyrics were most unsuitable: “To me LSD, opium dens and suchlike are out.”

According to Schmidt, when Pryme called the song’s writer, asking what to do because they were going to question him about LSD, Petersen replied, “Say you tried it in Australia so they can’t arrest you” ... and he did.

“A former Taranaki Herald and Truth reporter such as Pryme,” Schmidt says, “would also know there would be a lot of publicity and ‘all publicity was good’ – especially for a star who’d been concentrating on television and cabaret work.”

Schmidt considers the song Pryme’s best: “Petersen’s simple image of walking with his wife in the park tripping was enhanced by the House of Nimrod’s production team – arranger Jimmie Sloggett and engineer Bruce Barton – who introduced wind and other sound effects helping to turn it into a minor-league pop classic.”

That song however, came towards the close of Pryme’s pop career.

After the Octagon releases (ballads and rock’n’roll covers) he’d recorded for Benny Levin’s Impact (‘A Star Is Born’ in late 1966) he then – with impresario Phil Warren’s guidance – appeared on the Festival label for ‘Gracious Lady (Alice Dee)’ and two singles for Pye. And that was it by 1970.

Given how high his public profile had been, Pryme’s private life had remained off-limits, although in one unusual instance it was – consciously or otherwise – hinted at.

In late 1968, just three months after the LSD controversy, an article in Auckland’s North Shore Times Advertiser – quoting him about the state of the entertainment industry – mentioned that he lived in a beachside flat at Thorne Bay, which he shared with hairdresser Philip Bailey and his manager Tony Katavich.

What the article didn’t say was that the latter was well known in the gay community and a courageous advocate for the rights of homosexual men. Yet in many ways, like Pryme, he was also a private person.

That paragraph in the Advertiser however had all the coding many would recognise, something akin to circumspect obituaries in British newspapers which would include the loaded sentence, “He never married”.

In 1970, Lew Pryme appeared at a Royal Command concert before Prince Charles and Princess Anne, as well as for inmates at Mt Crawford jail with two of them on backing guitars: “The audience was fine and the backing was great,” he would say.

Pryme became one of the most important figures in the industry.

But he was moving away from the spotlight and into management and public relations. By then he was well connected and respected in the country’s wider entertainment scene and when a syndicate he headed bought Fullers Entertainment Bureau – Auckland’s leading booking and management agency – from Phil Warren in July 1972, Pryme became one of the most important figures in the industry.

As the Herald noted in December 1973, Pryme and his business partner Bruce Warwick were responsible for promoting Christmas and New Year entertainment in various resorts, with American eccentric Tiny Tim being among the artists.

That same year Fullers had raised its commission on artists’ fees from 10 to 15 percent and Pryme negotiated – talked around, might be a better way of putting it – Actors’ Equity into accepting the increase.

In 1973, he also spotted young soul singer Mark Williams, lead vocalist of the Dargaville band Face. Encouraging him to go solo, Pryme signed Williams to a solo management contract, and took him to Australia the following year.

“He could read the market very well,” said Williams later. “I relied very much on what he said.” Pryme managed Williams until 1976.

In 1975, the same day Pryme was elected president of the Variety Artists’ Club, Williams won the VAC’s golden microphone award and one of Pryme’s bands, Footprint, came runner-up in a Battle of the Bands competition (behind Think).

As reports at the time noted, Pryme was also Auckland president of Actors’ Equity and a committee member of NEBOA (the National Entertainment and Ballroom Operators’ Association), which ran the Entertainer of the Year award.

He was outward looking in his approach and in 1975 when Ray Columbus – New Zealand’s Entertainer of the Year at the time – was robbed of the chance to appear on the high-rating Dinah Shore Show on US television because of a union ban on overseas artists, Pryme took a pragmatic but clear-eyed approach: “Australia is taking a much tougher approach to imported artists in order to protect their own entertainers,” he said, “and we will have to try to negotiate some reciprocal arrangement. It looks as if we might have to extend this type of arrangement to the United States and Britain.”

He himself had been denied the opportunity to travel to the US earlier in his career, when his visa took too long to process.

Going into the 1980s, he also astutely managed Tina Cross and Rob Guest, taking them into Australia as mature artists and giving them a life in the mainstream beyond pop and disco. He also handled the careers of Derek Metzger, David Curtis, Suzanne Lee and others. Lee won the Variety Artists’ Club award as the year’s most professional entertainer in 1983, a fortnight after appearing on an international young performers contest in Prague which was televised and screened across Eastern Europe.

By this time Pryme had long since ceased to be known for his pop career and his private life remained very much that. He accepted the role as inaugural executive director of the Auckland Rugby Union in the early 1980s, in the years after the debacle of the Springbok Tour, introducing large showbiz-styled shows to Eden Park in 1986. He brought the crowds back but not without some controversy.

He leveraged his entertainment sensibilities to the promotional aspect of his role and always had an eye for spectacle. In 1971 he produced an elaborate multi-star, song and dance revue show for the Ranch House in Auckland’s Birkenhead and later organised The Greatest Show on Earth for Inglewood, which included a troupe of Native Americans “complete with war paint and other props,” according to the Herald.

Pryme knew what the rugby audience wanted: entertainment

In many ways he dragged rugby into the professional era with sensibilities he’d honed in that now-distant career on stage, as someone who knew what audience wanted: entertainment. And family entertainment at that.

Former All Black Grahame Thorne later said, “He changed the shape of Auckland rugby. We talk about [famed rugby administrator] Tom Pearce … if Tom had seen [Eden Park] with the cheer girls he’d be spinning in his grave.”

Pryme loved rugby and in the 1980s co-hosted a radio rugby show on Radio Pacific with Tim Bickerstaff. A career peak for him was the 1987 Rugby World Cup: he organised the opening ceremonies, and he was there for the final day when the All Blacks beat France.

In 1990, the year of his death at 51 from Aids-related illness, Lew Pryme and his partner Jeff (who died a week before him) were the subject of an insightful and honest documentary by Max Adams and Amanda Miller.

It was entitled Welcome To My World, named for one of his pop-era songs.

Even though he had to resign from the Auckland Rugby Union due to ill health, Lew Pryme didn’t share his secret with his family, close friends or the rugby fraternity.

In that moving doco, filmed up to the closing days of his deteriorating life – when he voluntarily stopped treatment – he said that if his condition was known, the reaction in the rugby world would have been “horrendous”.

“But I don’t think that’s just typical of rugby, it is typical of a lot of the community. There would be a lot of people saying, ‘Oh that nice bleached pop singer. It couldn’t be him.’ But it is.”

--

Graham Reid acknowledges the work of Andrew Schmidt and the makers of the documentary Welcome To My World in the preparation of this article.