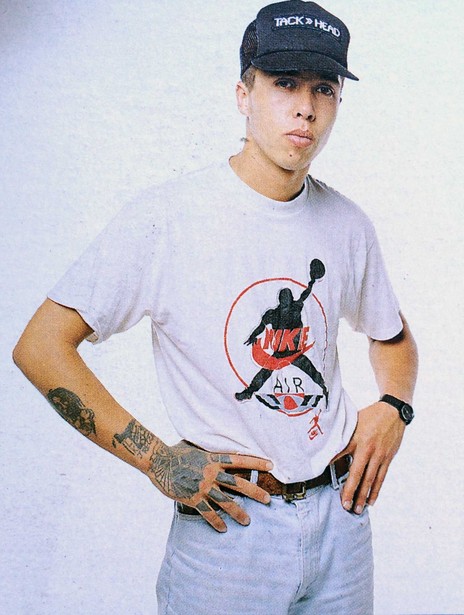

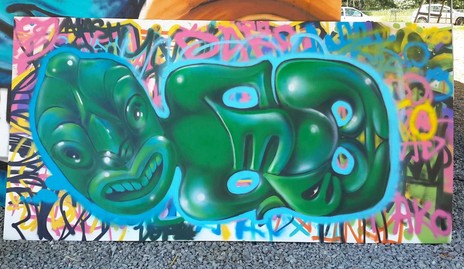

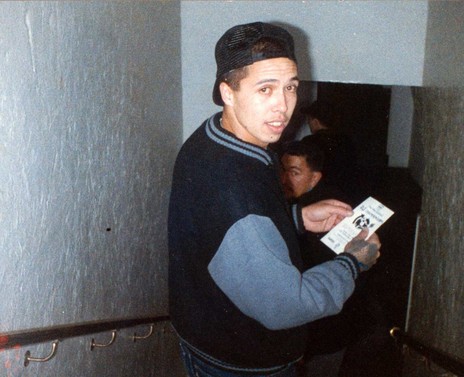

“The first time I saw graf was in that film The Warriors, about a gang getting across New York and they had a tagger with him,” he says. “Then there was the video for 'Buffalo Girls' [by Malcolm McLaren]. But I became a fully-fledged writer the day after Style Wars showed on television in 1984. It was the Tuesday documentary, on Wednesday I was a writer.”

The other most important change in DLT’s life was befriending Dean Hapeta, another local kid from Upper Hutt with a love of hiphop. The pair joined with other friends to form a breakdance group, catching a train into Wellington to perform on the streets. They also shared a love of Gil Scott-Heron, Bob Marley, and dub poets like Linton Kwesi Johnson, Michael Smith, and Mutabaruka, while their reading expanded to include The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Seize The Time by Bobby Seale.

The Posse

DLT remembers that his first move towards music was playing drums in a four-piece reggae band with Hapeta’s younger brother Matt (aka Wiya) and Aaron Thompson (aka Blue Dread). “We were kids from the same neighbourhood – we hung out. We had the same ideals. We weren’t the kind of guys who went about hassling people like – “who are you, who are you?” But when someone frowned upon us, we gave it back. We were driven by self-pride. We were sixteen years old. No prejudice against no one, we reacted to what we saw ...

“We had reggae here before rap music. If you study what was available from 1972 up until [Mel Melle of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five] released ‘The Message’, it’s a natural path. All the English chatters were rapping really – the way they toasted in patois in between songs. By the time Melle came along reggae had got us ready for it. They’re related to the max. They’re forms of music that have come from oppressive realities and are about working a way out.”

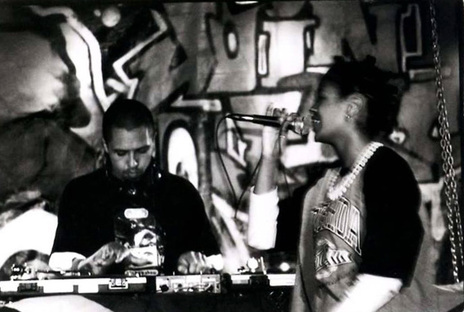

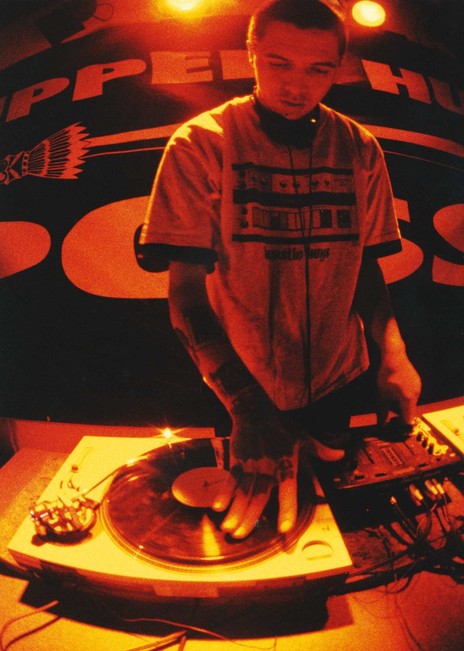

When Hapeta began rapping as D-Word, DLT taught himself to scratch records so he could back him. “We got a drum machine – a Roland 707 – and we used a normal turntable off a stereo and a regular amp. There was no mixer with a crossfader. That’s how the scratching on ‘E Tu’ was done.”

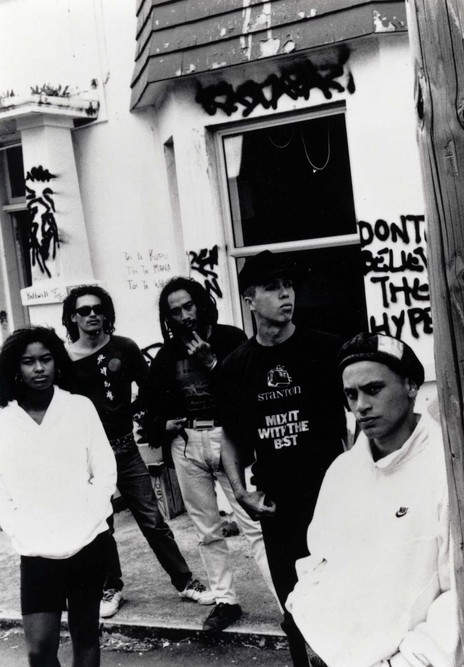

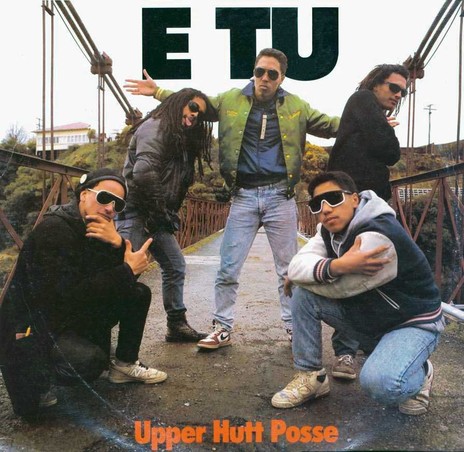

This led to the original four-piece reggae group – the Upper Hutt Posse – turning into a hip-hop group with the addition of rapper Bennett Pomana (B-Ware), 14-year old singer Teremoana Rapley and singer Steve Rameka. They won a rap contest in Taita arranged by promoter George Hubbard, who soon became both their manager and a key collaborator when it came to recording in the studio since he had experience with drum programming and sampling. The prize for the competition included studio time and they used this to record their first single.

In 1988, the music video for ‘E Tu’ hit television screens and was shocking on multiple fronts. The sharp historical references to the New Zealand land wars immediately recast the US art form of hip hop in local terms. At the same time, rap crews in Auckland were horrified that they’d been beaten to the punch by an unknown crew of Wellingtonians and many found themselves asking, where the hell is Upper Hutt anyway?

Upper Hutt Posse released their debut album Against The Flow in 1990, through newly established Auckland label Southside Records.

DLT soon found Upper Hutt Posse being asked to play regularly in Auckland. “At the beginning, it was good, because everyone was buzzed about going to big dance parties, which had just come to New Zealand – a thousand kids at a venue with turntables and live acts. We were on the front of that and got by for a while because we were mixed up amongst Total Effect, Semi MCs, Houseparty, UCD, MC OJ and Rhythm Slave, Double J and Twice the T, Spell and Jam. Welli was a different story – we performed the pub circuit down there. We left Welli because of that – there weren’t any hip hop venues.”

Upper Hutt Posse released their debut album Against The Flow in 1990, through newly established Auckland label Southside Records. One of the label owners, Simon Lynch, also co-produced six tracks on the album. At this stage, DLT was still working with a limited DJ set-up.

“At some point during the recording of the album, we borrowed a mixer. It was hard core because I had to learn it on the fly while recording it. I didn't have a mixer at home to practice on or anything like that. In 1989, when we moved to Auckland, we got lots of gigs so I did eventually get a better set-up, but it was still only one turntable. All the photos from back in the day, you can see that I've only got one turntable and a mixer.”

DLT was given the chance to do a remix of ‘Against the Flow’ when the title track was released as a single. “That was the first time I went in the studio and had full control of a recording. I used a Roland 900 sampler and worked with Terry Moore from The Chills. It was strange because he was such a Dunedin guy – he was Flying Nun hard out. I borrowed the sampler off the [Twelve Tribes Of Israel] guys. I was doing stuff on the side with Kevin Rangihuna. That's why he features on a lot of my stuff. The Rastas were the first guys that I went in the studio with and just watched how they did things. It was all analogue, but because Kev was a keyboardist, he was keen to go digital.”

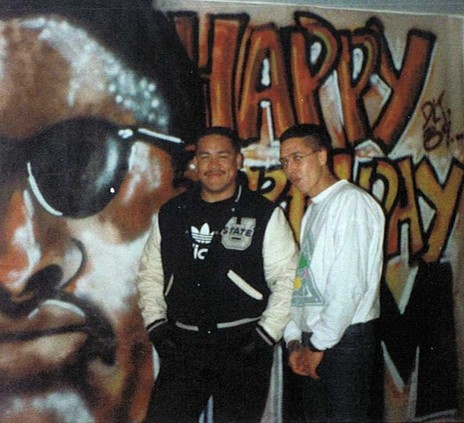

Upper Hutt Posse’s growing notoriety led to further exciting opportunities, including opening for Public Enemy and visiting the USA as a guest of the Nation of Islam, which was a particular highlight for DLT. “They were Malcolm X’s people. Malcolm was our older brother. We had that ahi kā – that fire in us. No one said it was okay to express it, except Malcolm.”

On the downside, the mainstream media often tried to stir controversy around the group. The Truth newspaper reported they’d caused a “race riot” when they told Samoan audience members to “go back to Samoa” and the Auckland Star claimed pākehā students were turned away from a university gig (a defamation case followed the latter and the group settled out of court after receiving an undisclosed sum from the newspaper).

DLT still recalls the anger the group felt at their treatment. “I try my hardest not to remember so I don’t go utu their asses. I set out to find the goodness and truth. I try not to carry vendettas. At least we were prepared for that happening since we’d read Seize the Time and Malcolm X’s autobiography.”

Joining forces

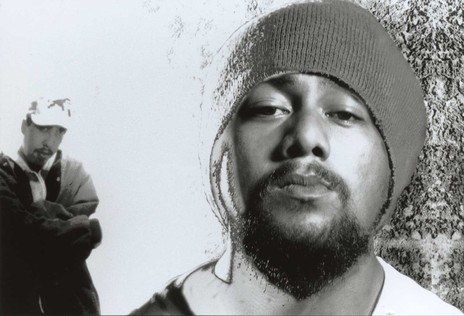

After a few years in UHP, DLT decided he wanted a little more creative freedom and so he left to form a new crew called Native Bass, but when they travelled to play Wellington, they found there was another group already called Tribal Bass so they switched their name to Dam Native.

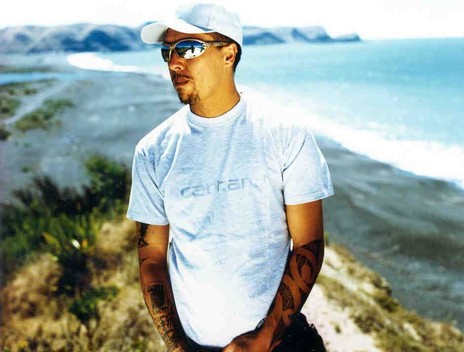

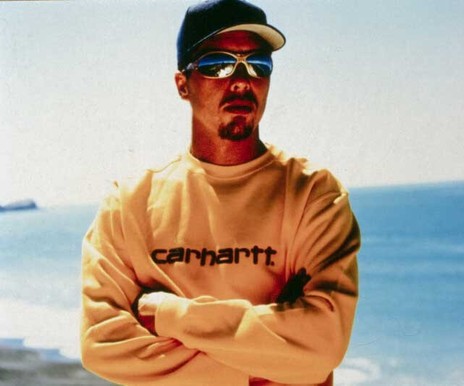

Meanwhile, DLT was also creating a name as a DJ in his own right and new opportunities soon came through this work.

Meanwhile, DLT was also creating a name as a DJ in his own right and new opportunities soon came through this work. He was asked to produce a “Madchester” influenced band called Melon Twister. “The Woodruffe brothers owned the Studio Art Supplies store and were looking for a producer. This is how I met Kirk Harding – he was a friend of theirs. He came into the studio and had a listen. That's how we met. He was already working at the record company [BMG] and he asked me for some demos. So I gave him a C-90 of Native Bass stuff.”

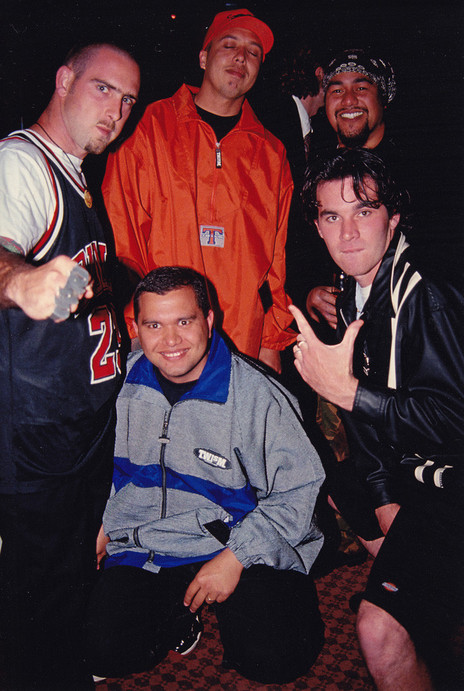

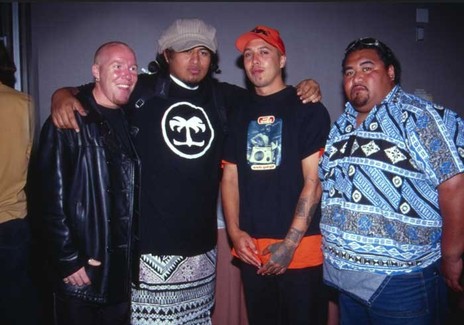

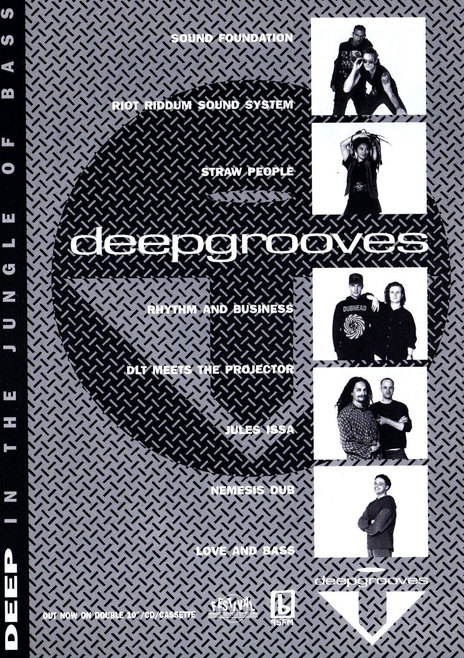

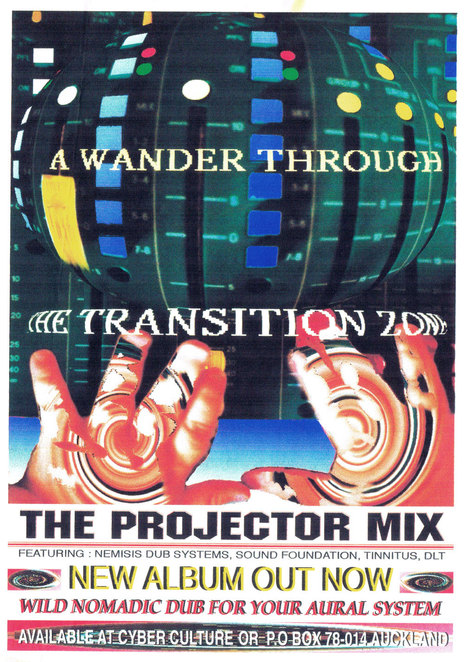

Another inadvertent hook-up came when DLT joined a line-up of acts supporting Supergroove at the Dog Club (later known as Dog’s Bollix) and this included Big Matt, ANC Dread (aka Antsman), Dubhead, MC OJ and Rhythm Slave, Tuffy, and Slowdeck. The show took place under the name Dog Club Stylee and this led to many of these acts deciding to work together as the Stylee Crew (later changing their name to 37 Degrees Crew with the addition of DJ Roger Perry). Many of these acts released music via the newly established label, Deepgrooves, which featured DLT on a couple of their compilation albums. One of his tracks was a collaboration with Mike Hodgson (one half of electronica group Pitch Black), who provided projectors for many of the warehouse raves that DLT was playing; the track was released as DLT meets the Projector.

DLT also gained an opportunity to DJ on the radio. “Around 1993, my friend who was a DJ went overseas and asked me to fill in for a couple of shows. His show was reggae-ish and my stuff was hip hop-ish, but the response was good. The programme director was Dominik Nola and she said, ‘You should do your own show for a couple of hours a week.’ I knew Sir-vere because he was in UCD, who were a performing crew from South Auckland back in the day. He was the DJ. We hung out when we did gigs together and we also got together on the basketball court, we shot heaps of hoops. So we became friends that way. So when these people from the radio station asked me to do a show, I asked him to join me as well. I trusted him because he had impeccable discipline. That was the True School Hip Hop Show. Within five years, we were doing the radio show and a TV show [on Max TV] of the same name as well.”

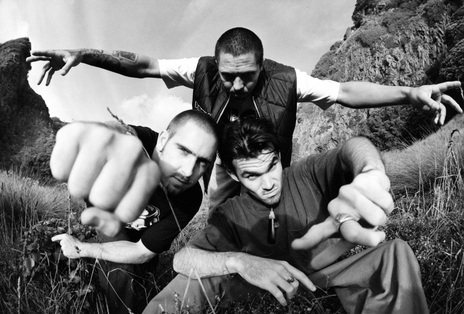

This didn’t stop DLT remaining a regular on the live DJ circuit and this sometimes led him to work with party rappers MC OJ and the Rhythm Slave. When the pair decided they wanted to move in a heavier direction, they brought DLT on board to form Joint Force.

DLT recalls that the other key force behind the group was Angus McNaughton at Incubator studios.

“That’s when I first went the whole hog with Angus and spent hours and hours in the studio with him. I had a huge respect for the role of the drum machine during the early days of hip hop. The 808 kick drum was the foundation of all my beats then. I had a 909 because of my love of Schoolly D and Mantronix. I loved the LinnDrum – the originals of ‘Chains’ were written on a LinnDrum. Angus liked gear so we'd talk about it, then we'd find these things. It was $700 for a LinnDrum back then, because they were considered trash. Even 808s were easy to come by then – we had four or five of the bloody things.

“So the sound was partially driven by that gear, but at the same time, I always went back to loops of James Brown or Todd Terry. I like the richness of the middle frequencies of loops. I wanted my music to swing because I associated Germanic four-on-the-floor with hard, uptight dance music. I wanted it to have that groove – that [Clyde] Stubblefield feel. It was the early days of techno and handbag house – at the time we thought it was terrible, but it was actually real soulful compared to what came later on.”

Joint Force develop a slightly distorted, bass heavy sound that reached further towards the underground edge of US hip hop and although they only managed one EP, it was a stepping stone towards DLT’s own breakthrough album.

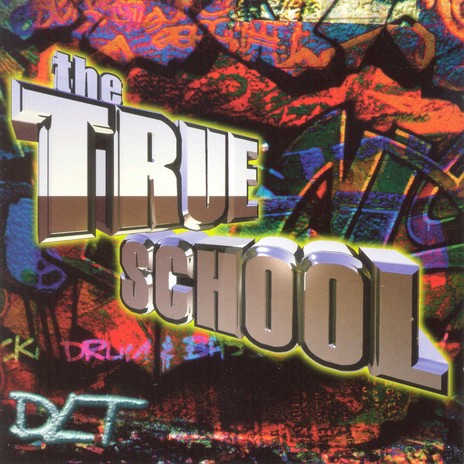

The True School

The pieces had fallen into place for DLT. His production skills had reached the point where he could make the beats he heard in his head into a reality and his solid working relationship with Angus McNaughton meant that the result was a full spectrum assault. His early connection with local rap guru Kirk Harding meant that he now also had the backing of BMG (and the label would soon also hire DLT's old friend, Sir-vere). “Morrie Smith [from BMG] was like a father to me and he was a hero to New Zealand music, especially Māori music because he signed Howard Morrison, Prince Tui Teka, Dennis Marsh, myself, Che Fu.”

DLT gathered around him a close set of rappers and singers that he knew from the live scene, including his old UHP bandmates B-Ware and Teremoana Rapley; ragga toaster The Mighty Asterix; New Zealand-Chinese rapper, Manchu; Mark James (aka Slave / Rhythm Slave); and even psych guitar legend Billy TK.

Yet, it was the inclusion of Che Ness from Supergroove that had the biggest impact, with the young funk singer morphing perfectly into an R&B singer and rapper under the name Che Fu.

DLT had the perfect beat – a bootleg remix that had been released on vinyl – which he then sent through layers of effects accentuate the crackle and crunch of the original. He played it to Kirk Harding, who loved the track but pressured him to keep working on it, forcing it through 13 iterations, before settling on a version that still had all the dirt of original, but punchy keyboard stabs in the chorus that lifted it into a more pop direction.

His pent-up creative energy came to the fore on ‘Chains’, a No.1 single that knocked overseas heavyweights Nas and Lauren Hill off the top of the charts.

Che Fu first met DLT when Joint Force toured the country in support of Supergroove and he’d lapped up the different sounds he heard coming from his tourmate’s quarters. He had little chance to write his own material in Supergroove and so his pent-up creative energy came to the fore on ‘Chains’, a No.1 single (entering the chart at No.2 on 21 July 1996, hitting No.1 on 4 August and quickly going platinum while it held the spot for five weeks) that knocked overseas heavyweights Nas and Lauryn Hill off the top of the charts. The True School (1996) also found chart success a few months later, reaching No.12 – a stunning accomplishment for Aotearoa’s first hip hop DJ album.

At the 1997 NZ Music Awards ‘Chains’ was named Single of the Year and won the Best Songwriting award while Che Fu was named Best Male Vocalist. In 2001 ‘Chains’ was listed at No.22 in the APRA Greatest New Zealand Songs of All Time.

Worldwide

The success of The True School was another sign to mainstream New Zealand that rap music wasn’t just an overseas trend that could be ignored. DLT reiterated this point by running a rap competition on the MTV show, Wrekognise, which he did with Sir-vere. “We got sixty-six entries on video tape [including early demos by acts like Ill Semantics and Four Corners]. To me, it was just an exercise in showing society what they were dealing with. It was only ten years before that music in New Zealand was ninety-four per cent white male rock, six per cent others. But rap was taking over, right across the board. It was on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine and even The Rock ended up playing rap music – only a few years before that their slogan was ‘no rap, no crap’.”

DLT’s next album would up the ante by trying to place local hip hop in a worldwide context. He reached out to artists from across the globe to contribute to each of the different tracks, drawing in top level acts from Canada (Rascalz and Kardinal Offishal) and France (Saïan Supa Crew) then putting them alongside local rappers (such as KD and Son Tan from Lost Tribe). He also worked with Dave Dobbyn on a remix of ‘Madeline Avenue’ and in an odder match-up, brought on board Nick Roughan (formerly of the Skeptics) as his sound engineer.

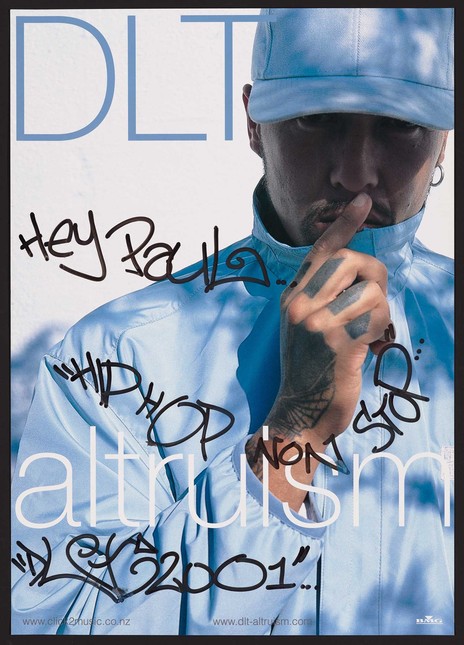

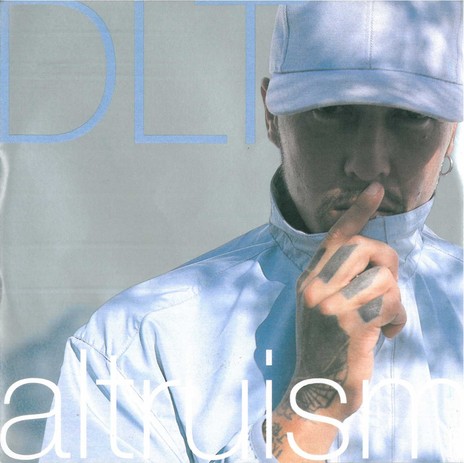

In 2000 DLT’s track with two underground rappers from New York, 'I'm Your MC' (feat Sage and Gravity) hit No.19 and the album, Altruism, hit No.9 soon after.

Meanwhile, Dawn Raid took a similar approach on Southside Story 2, interspersing their own acts with underground MCs from New York to give the album an international flavour. These releases helped provide the groundwork for the explosion in local hip-hop that would take place a few years later with Scribe, Deceptikonz and P-Money becoming household names.

However, DLT found that BMG was no longer the supportive backer of his music that it had once been. “Because of downloading at the time, the record company was dropping artists like flies. Out of the twenty or so bands that they had on their roster in 1998, I watched them all get dropped. I was the last one standing, only because I was in mid-production when they sent in this scumbag from America to close it all down. He got rid of bands like Shihad, all these great bands. When downloading first came around, the record company was getting by on the fact that DVDs were $125 and they were killing it. That, along with Elvis’s catalogue, was what was paying for us to exist. But downloading soon killed DVD sales as well.”

The result was that just as hip-hop in Aotearoa was taking centre stage, DLT was making his move away from the limelight. By this stage, he had two children and the late nights of a DJ and performer no longer held much appeal for him. He started his own label, Machaventa, with Morgan Donoghue (EMI, later CCO at Serato) and Chris Caddick (EMI). His first signing was going to be No Artificial Flavours, a group that included a longtime fan and supporter of the True School Hip Hop Show, Taaz. However, DLT soon began to feel that EMI was more interested in finding another Bic Runga than another Che Fu, so he decided to walk away from the music industry.

Can't stop, won't stop

When Upper Hutt Posse received an Independent Music “Classic Record” award at the Taite Prize event in May 2016, DLT was unable to attend since he’d just got back from helping run an artistic workshop in New Caledonia. “Me, Bill [King Kapisi] and Teremoana went over to give graffiti workshops and teach the kids there how to print T-shirts, how to rhyme and how to make beats. I’ve done that work in Australia too and all over the world since the nineties really. I taught kids at the Waipareira Trust in the nineties that went on to be world-recognised graf artists. Anything to do with hip-hop – real, elemental hip-hop – we’re there. I don’t breakdance anymore because I’m too old, but I can’t help but watch it online.”

His love of art remains a central part of his life. “The art was always there. I live to carve rocks and I doodle a lot in my downtime. Ever since I was a little kid I’ve drawn. The graffiti part was just another way to help promote freedom of expression, especially from the hood. The element of politics is still there. Absolutely. Recently I did a mural about TPPA. Hip hop for life. I’ve tried to walk away a couple of times and I can’t. You don’t spend twenty years doing art and then stop. I still do it today, I was painting yesterday. My music and my art always ran parallel, though the music game is what really promoted me. I did nineteen years on the radio too, the radio DJing and doing gigs, that’s really separate to production. The reason I got out was the way Hollywood and the recording industry started exploiting hip-hop. I’m fifty and I don't want to pretend that I’m twenty-nine for the rest of my life.”

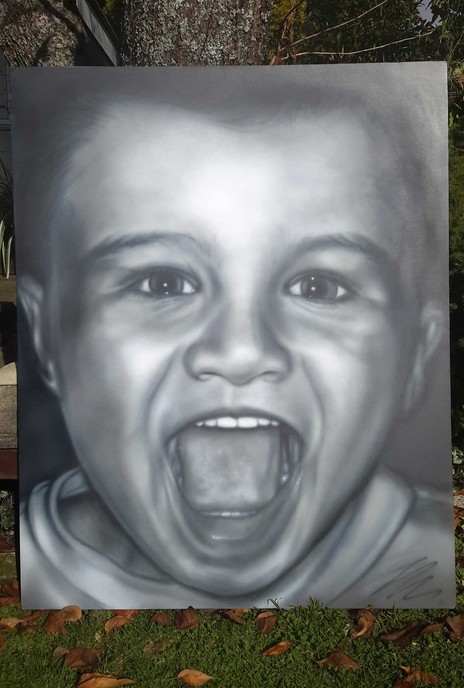

These days, he considers his main goal is to raise his kids. “I got six now – three I made and three my partner made. I’m about to become a grandfather. They can all draw. They know the fundamentals of breakdance. But I tell the kids, don't do hip-hop, stay at school! I have a stepdaughter who is a ten-year-old gymnast and when I show her a B-girl move, she can do it first time. It’s fantastic. But it’s cool bro – you spend your time teaching them what swag is and what style is. Don’t try to be like us and wear shell-toes and fat laces – no, no, no. You’ve got to carve it out of the new world. I don’t force old-school fundamental hip-hop stuff on them, no way. I tell them what I’m about and why, but when it comes to me having a number one single and all that – they’re like, ‘So What?’ My seven year old adores Altruism, but that’s just because it’s got me on the cover!”