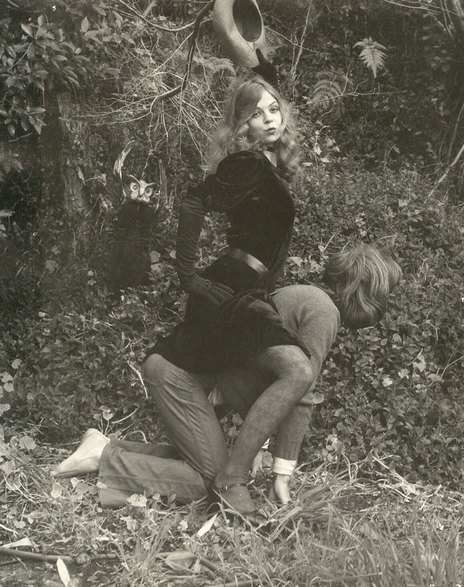

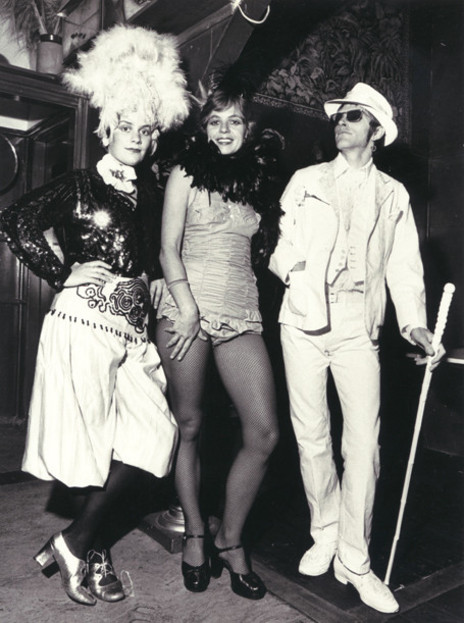

Deborah Hunt of Red Mole, on stage at Carmen’s Balcony, Wellington, 1977. - from Bus Stops on the Moon

“Some day all theatre will be like this,” declared the iconoclastic Red Mole. Founded by actors and writers Alan Brunton and Sally Rodwell, who were joined by the fire-eating Deborah Hunt and others, the troupe performed Dadaesque cabaret, agit-prop, costume drama, street theatre, circus, and puppetry. Also, live music: musicians performing with them went on to have long careers. Martin Edmond has written a memoir of his years as a Red Mole actor. This edited excerpt from Bus Stops on the Moon: Red Mole Days 1974-1980 describes 1977, when Wellington audiences witnessed the long-running show Cabaret Capital Strut. The venue was Carmen’s Balcony, run by the city’s most prominent drag queen and nightclub proprietor. – AudioCulture

--

Carmen, née Trevor Rupe from Taumarunui, was an imperious Māori drag queen who ruled unopposed over Wellington’s night life in the 1970s. She ran for mayor, unsuccessfully, in 1977. Her slogan was “Get in behind!” I voted for her.

I can imagine a Red Mole conversation that began along the lines of “What are we going to do when we get back to Wellington?” and ended with a determination to approach Carmen and ask her about using The Balcony for Sunday night shows. Deborah and Sally had already worked there, dancing a tango, usually to ‘Hernando’s Hideaway’. They called themselves César and Rosalita. Deborah, in top hat and tails, was César; Sally, in a low-cut red dress, Rosalita. Both were effectively topless.

Jan Preston and I went along to The Balcony one Sunday night in February 1977 to check the place out. It was in Victoria Street, on the corner of Harris Street. A wooden, two-storey building; Carmen had the second floor. You walked up a steep staircase, at the top of which was a reception desk; behind the desk sat the formidable Jeanette McDonald, with ultimate power over who did or did not enter the room.

Inside was all red plush and gold leaf, curtained and mirrored, darkly lit: a rectangular room with the stage at one end and the bar at the other, on your right and left, respectively, when you entered. The stage was small, with two even smaller dressing rooms either side.

Sally Rodwell and Alan Brunton, Wellington, 1976. - Bryan Staff

The stage gave onto a catwalk that extended a third of the way into the room. There were thin tables with thin chairs clustered along the sides of the catwalk and also at its end; behind that, standing room only. The bar, though illegal, was functional: it served spirits – whisky, bourbon, brandy, rum, gin, vodka – with mixers. There was a bulbous red light, the size of a clenched fist, like one of those on the tops of cop cars, concealed beneath the counter. It lit up whenever Jeanette pushed the warning button she had under her desk outside; and then, “as if by magic”, the bottles of spirits would disappear.

In truth, visits by the police were rare and always carefully managed. They knew the set-up and made sure the bar staff had plenty of time to hide the booze so that they could then inspect an obviously innocent operation and give the all clear. This arrangement continued throughout Red Mole’s tenancy. Perhaps someone was being paid or perhaps, more likely, Carmen knew things that ensured people would rather not upset her.

The night we went to The Balcony there were just five other patrons there. They were Korean sailors off a squid boat in the harbour, lounging together at a table on the far side of the catwalk, still in their work clothes, looking up impassively as the queens paraded, to current pop hits played through a tinny sound system, and gradually shed most of their already skimpy clothes. It could not have been duller. Or sadder, for that matter. The place was, in truth, ripe for the plucking.

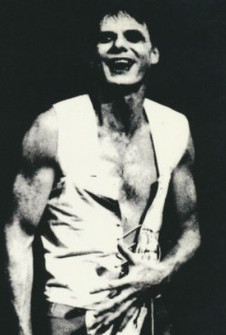

Alan Brunton, Red Mole.

“So was born Cabaret Capital Strut,” wrote Alan Brunton in Salient, “… a two-buck deal of theatrico-musical fun and fare that promises to put Sunday back into the weekend.”

Cabaret Capital Strut’s irrepressible vulgarity was replete with examples drawn from contemporary pop culture and from revolutionary, high-art cabarets of the past: Paris during La Belle Époque, wartime Dada and Futurism, Weimar Germany. Lubricious and dangerous Wild West saloon entertainments also made a contribution to the mélange.

Alan had a vast knowledge of, particularly European, avant-garde strategies, and he and Sally’s travels in South-East Asia also contributed. Elements from these disparate cultures flowed into the cabaret and especially into Red Mole’s mask-making and story-telling.

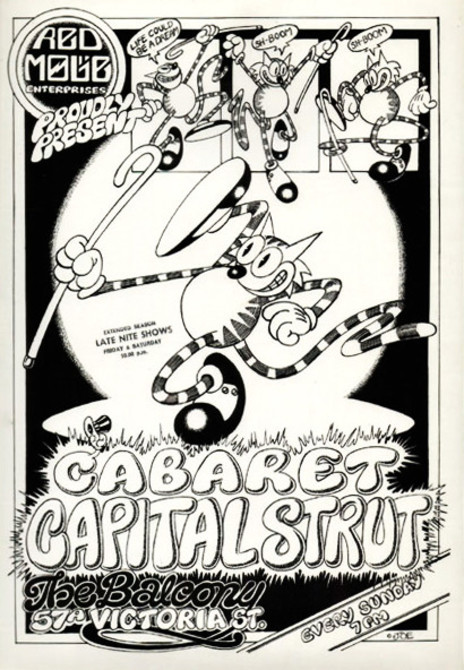

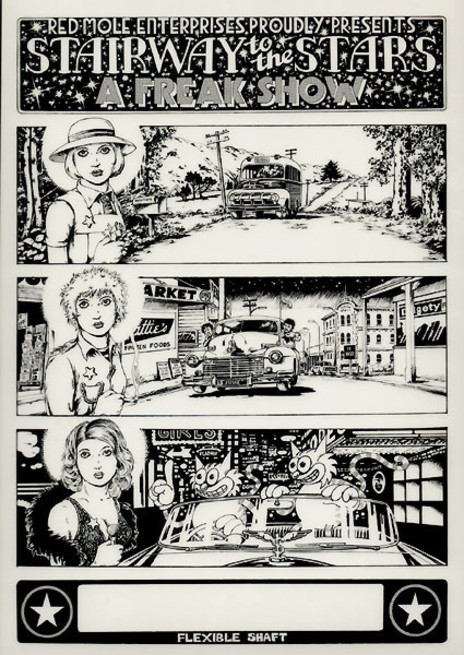

Rock’n’roll too. The inaugural poster, by Joe Wylie, emphasised the recently contemporary. It featured a cool cat with a cane, dancing in the glare of a spotlight. Above, in a three-part miniature strip, in a set of related moves, that same cat, leaping out of his frame, announced: “Life could be a dream … sh-boom … sh-boom.” That doo-wop song, sung by the Chords, came out in 1954. “If I could take you up in paradise up above …” And the cabaret did indeed become a sort of waking dream, in which the paradisial, mingled with the satiric and the apocalyptic, opened into a fourth space that was profoundly and unapologetically hedonistic.

Red Mole’s Cabaret Capital Strut poster, by Joe Wylie, 1977.

The set list for the first cabaret survives; it’s a page long. Alan remarked later that each of the set lists for the cabarets that year fitted onto a single A4 page. This one was in three parts. Doors opened at seven and taped music played as the patrons rolled in. The band, Meantime, performed an overture: jazz and blues. The opening sketch was a satire about the Queen, impersonated by Sally. It was followed by the introduction of the MC, Arthur Baysting, and segued into his number, ‘Brazil’, with Jenny Stevenson dancing. Chanteuse Kris Klocek, from local band After Midnight, sang ‘Falling in Love Again’, the song made famous by Marlene Dietrich in the 1930 film The Blue Angel. The last act before the first interval was called ‘Connection’ and starred Sally and Deb with Jan “+ Martin Edmond”. I was shocked when I read that. I have no recollection of it.

There was a musical break, a piano player, New Yorker Jonathan Besser. Two Futurist plays were performed: Dissonance, by Francesco Cangiullo and Towards Victory by Corra and Settimelli. During the middle section Jan played Stravinsky (Circus Polka for a Young Elephant), Jenny Stevenson performed a gypsy dance, Alan did some satire; nowadays we’d call it stand-up.

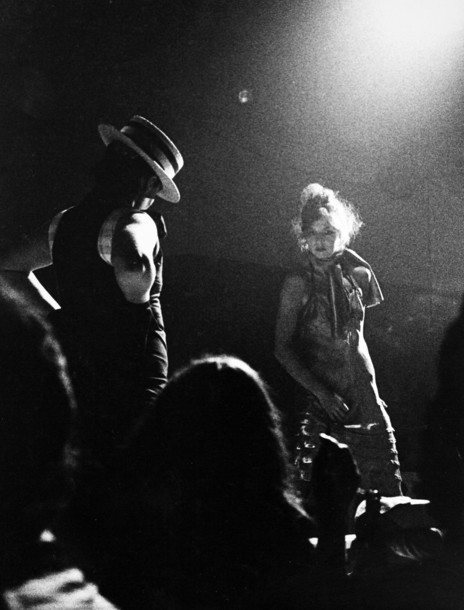

Sally Rodwell at Carmen’s Balcony, Wellington, 1977. - from Bus Stops on the Moon

Futurists endorsed vaudeville, music hall and variety shows because those forms lacked a history and, concomitantly, always attempted to involve the audience directly in the performance. Red Mole did that too. You couldn’t watch the shows passively or they wouldn’t make sense. It is a moot point, however, if anyone at Carmen’s actually knew they were seeing Futurist plays. Towards Victory was followed by a tap dance, a blues dance, another Kris Klocek song and then Sal and Deb did the tango. After the show was over, Meantime played again and people stayed around to drink and dance.

A reviewer suggested that Red Mole had “overthrown any singular notion of what theatre might be”.

The door was $384, which suggests 192 paying customers. The lights cost $100 and various other expenses – band costumes, laundry, candles, printing, piano tuning – accounted for another $100, which also included rent of $16. Twelve people, including the floor manager, Deb’s brother Tim Hunt, and the sound man, Peter Frater, received $10 each. The band got 40 bucks. I’m not on the list of those who were paid, suggesting that I didn’t perform after all. Catering was by Peter Fantl. The profit for the evening was $25. It was a full house; for the rest of the time Red Mole played Carmen’s, remarkably, the house was never less than full.

Deborah Hunt and Sally Rodwell of Red Mole, with Neville Purvis (Arthur Baysting) backstage at Cabaret Capital Strut, Carmen’s Balcony, Wellington, 1977. - Red Mole archive/New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre

Two things people reliably remember about Cabaret Capital Strut are concealed in this brief summary of the proceedings. One is item 3 on the set list: “Arthur Baysting, Emcee + continuity.” This was the first public appearance of Arthur’s much loved, much abused alter ego Neville Purvis. ‘Neville Purvis, at your service,’ he would say. “That’s Neville on the level to you.” Neville was a spiv, an outsider. In his fiction, he wasn’t part of Red Mole: after he’d got out of Mount Crawford Finishing School – jail – they’d asked him to come and lend them a hand.

He told shaggy dog stories and jokes that were funny in a bathetic, low-key kind of way. Asked what the Hutt Valley was like before the Pākehā came, he dead-panned: “Miles and miles of empty state houses.” Neville was not, not ever, politically correct.

Neville was intrinsic to the cabaret. He strung things together, night after night; his thin white thread ran through the outlandish exotica of the rest of the acts. They could consist of anything, but there was one other character who reliably appeared, night after night, the way Neville Purvis did.

Called The Pig, s/he was played by Deborah Hunt, with pink papier-mâché ears and a pink papier-mâché snout held in place by black elastic bands; under a long black shirt, a pillow strapped across her belly and chest; black tights; a pink bow tie. She – he – it – resembled, Humpty-Dumpty-like, a bulbous torso with a big head and skinny legs. She was, of course, Muldoon, and in that guise bullied and charmed the audience, jeered and laughed at them, made them the butt of his vanity, his arrogance, his gleeful insolence; and so became a lightning rod for our own anxiety, our fear and our disquiet.

The essence of Cabaret Capital Strut was its freedom: we had no obligations to anyone or anything else, apart from those due to our own standards and our audiences’ proclivities. Any act that didn’t work was dropped; any that did, was pushed further, towards outrageousness. Delirium, ribaldry, sexiness, intoxication, hilarity. When we performed a parody of a punk rock band Deborah wore a meat bikini – cuts of sheep’s liver or cow’s heart over her breasts and her pubes. These would gradually decay until, after protests from other performers, they were thrown out and replacements bought.

Deborah Hunt blowing fire at Carmen’s Balcony, 1977. - from Bus Stops on the Moon

The eclecticism of the acts mirrored that of the audience. Up the back at Carmen’s you would meet all sorts: from junkie princesses to degenerate artists, from school kids on the lam to jazz musos slumming, from drag queens to future politicians. The cabaret was also innovative in the sense that the shows actually came out of a synergy shared between performers and audience, which created the dazzling multiplicity everyone enjoyed. This was perhaps its greatest achievement. Night of delirium, nights of power. Nights of remembering the forgotten years.

However the season at Carmen’s is divided up, it remains a remarkable achievement: nearly 100 performances over six months, none of which was exactly the same as any other. In August and September, Red Mole performed 37 nights straight, with people queuing round the block to get in and dozens being turned away from every show.

A big part of this success was down to the music, and the music came mainly from the Country Flyers, with Midge Marsden on vocals and harmonica, Richard Kennedy on guitar, Neil Hannan on bass and Bud Hooper on drums. The Flyers had a light clean melodic sound and an eclectic repertoire: anything from Chicago blues to Dr John, from Ry Cooder to Jimmy Cliff, from Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen to Little Feat. Midge had been in Bari and the Breakaways; he had his own weekly radio show on the NZBC called Blues is News; he owned a legendary record collection. The Country Flyers had a long-standing residency on Thursday nights at the Royal Tiger Tavern and built up a strong following there. Many of those came across to Carmen’s. There’d be dancing every night after the show.

Many other musicians came and went: Max Winnie, a guitar-playing folk singer who collaborated with Arthur on a sci-fi country skit; Mike Gubb, son of a shoe-shop owner, keyboard player extraordinaire; Andy Anderson; Rockinghorse (Wayne Mason, Barry Saunders, Clinton Brown, Jim Lawrie) who, during The A & P Show, stood in for the Flyers while they were on the road; Rick Bryant; Malcolm McNeill. Two stand-out performers were Blerta veteran, the vocalist Beaver (Beverley Morrison), and a young folk singer from Upper Hutt called Jean McAllister, whom Midge discovered and brought along. Jean had long straight black hair that fell down past her knees, a deft sense of humour, an acute memory and a laugh like the gurgling of water in a drain. She often quoted something her father, a Scotsman, said of her career choice: “It’s a very precarious occupation.”

Stairway to the Stars: a Freak Show - poster by Joe Wylie, 1977.

When we decamped for Auckland, Jean and Beaver accompanied us north and Jean went on to become a Red Mole regular. The Flyers didn’t have a keyboardist so Jan became their de facto piano player and learned how to play rock’n’roll. Son et lumière at Carmen’s Balcony was provided by the incomparable Peter Frater, whose history with Red Mole is long and complex, extends backwards and forwards in time and includes both miracles and disasters. Frater was a pioneer. In the early 1970s he wired up psychedelic light shows through a series of film and overhead projectors, from which his helpers occasionally got electric shocks, and projected mind-bending light shows straight out of the hippie scene in San Francisco.

There were dangers as well as pleasures. One night after the show at Carmen’s, when the band was playing and everybody dancing, Richard Kennedy stepped up to the microphone to sing and seemed suddenly to rise into the air for a moment before falling cataleptic to the floor: a near fatal electrocution due to an unearthed PA system.

Sally Rodwell, left, and Deborah Hunt of Red Mole, with Neville Purvis (Arthur Baysting) backstage at Carmen’s Balcony, Wellington, 1977. - Red Mole archive/new zealand electronic poetry centre

Actors joined the cabaret as well. Bill Stalker, TV star and Beaver’s partner at the time, did a couple of numbers: a version of ‘O Sole Mio’ as a disconsolate Neapolitan chef trying to attract patrons to his failing greasy spoon restaurant, and ‘Stupid Cupid’, the Connie Francis song, replete with mondegreens, in Back to the Fifties. Its cousin, The Sixties Show, included a parody of the TV soap opera Close to Home, called Close to Shame (“where no one uses their real name”). The theatre group Chameleon, with Aileen Davidson, came in for one of the themed shows and afterwards their dancer, Ian Prior, initiated a series of intricate moves that led to him joining Red Mole and coming with us to New York. Magician Timothy Woon, then still a schoolboy, showed how he could produce playing cards and coins out of his own naked torso. Murray Edmond appeared as a juggler, or jongleur, during The A & P Show.

Anyone who wished to join Red Mole could do so – as long as they had an act. Aspirants showed their wares to the company early in the week during rehearsals at Carmen’s and I don’t recall anyone being turned away. About 50 people appeared during the seven months. Nor were the queens forgotten. Maureen Price danced as a houri in The Arabian Nights, in which Carmen herself graced the stage with her formidable presence. She sang ‘Stranger in Paradise’: “That’s a danger in paradise/ For mortals who stand beside/An angel like you.” There are people in Wellington who still remember that performance.

At the end of that delirious run of 37 straight dates at Carmen’s Balcony we packed up and went to Auckland. We had been offered some shows at promoter Phil Warren’s Ace of Clubs, above the Cook Street Market downtown.

Why did we leave Wellington? The official story was that the lease on Carmen’s Balcony expired, but that was also said to have been the reason we took over the club in the first place. I asked Alan, on several occasions, why we closed Carmen’s at the height of our success, with crowds queuing around the block and money rolling in? He was, typically, inclined to give different answers on different occasions; not necessarily false or contradictory, just varying slants on a complex truth. The one I remember best is this: “It was the toilets. We just got sick of going in every morning and cleaning the toilets.”

I shuddered. I could imagine. The toilets at Carmen’s were small and grotty and, after a night of revelry, besmirched in inventive ways that only rock’n’roll patrons seem able to explore to their full potential. Surely, I wondered (but did not say), there was enough in the door-take to hire professional cleaners? But that was not the Red Mole way. Every cent would have been saved and dedicated to future enterprises.

There was more to it than cleaning lavatories, however. The Moles were nothing if not ambitious. Having épated, comprehensively, the bourgeoisie of Wellington, they intended to do the same in Auckland, and beyond. I think they already had their eyes on the prize: New York, the theatre capital of the galaxy.

--

Videos

Red Mole on the Road, documentary directed by Sam Neill, 1979 (NZ On Screen)

Radio with Pictures - Red Mole special directed by Gaylene Preston, 1980 (NZ On Screen)

Zucchini Roma, documentary by Sally Rodwell and Alan Brunton

--

Further reading

Alan Brunton, by Bill Direen, AudioCulture, 2018

Red Mole in Rip It Up, October 1977

Neil Hannan: Red Mole on the road in the US

Terry Snow on Red Mole, Art New Zealand, Winter 1978

Alan Brunton introduces Red Mole’s Cabaret Capital Strut, Salient, March 1977

Murray Edmond on Red Mole’s Cabaret Capital Strut, 1977

--

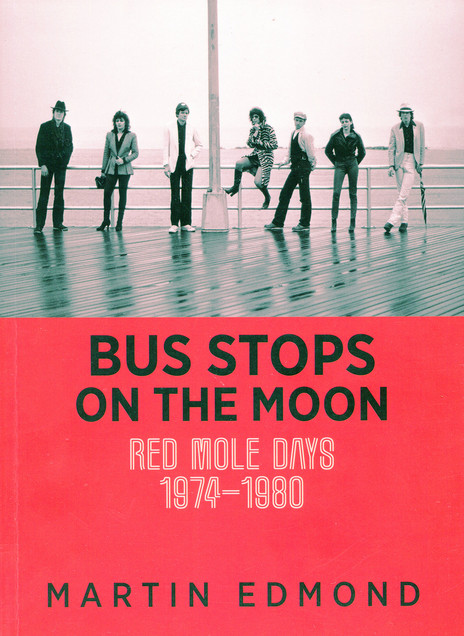

An edited excerpt from Bus Stops on the Moon: Red Mole Days 1974-1980, by Martin Edmond (Otago University Press, 2020). The cover image, by Joe Bleakley, shows Red Mole at Coney Island, New York. From left: Neil Hannan, Deborah Hunt, Alan Brunton, Sally Rodwell, John Davies, Jan Preston, and Martin Edmond.