The Neon Picnic location at Pukekawa, 66km south of Auckland, was “eerie” when Chrissy Duggan drove in to set up a women’s space. Discussions with the festival organisers had been “one-sided” but Duggan and friends had managed to get a space for $200 cash upfront. They hired a caravan, borrowed a Falcon ute, and arrived at a site that already seemed to be “in its death throes”.

There was no power except for an emergency generator: the festival organisers hadn’t paid a connection-fee deposit of $2000. “The crew from the side stage and the on-site builders were responsible for salvaging what little they could do to lift everyone’s flagging spirits,” Duggan wrote in Broadsheet two months later (she had been a Metro rock columnist in the early 80s). “They are to be congratulated for their concern, they had been there for weeks, some for months, without being paid.”

The news of the cancellation reached the Pukekawa site at 5pm on the Thursday, when the person coordinating the workshop area ran up the hill shouting, “It’s off, I’m really sorry, give me the keys to the caravan and we must have lunch.” Fat chance, wrote Duggan.

Any coordinators of the festival present disappeared quickly, afraid of irate ticket-holders and possibly workers. Stage crew hurriedly dismantled their equipment and headed back to Auckland. Trucks arrived from the breweries and quickly uplifted the vast quantity of alcohol on site, though the festival crew were left 20 dozen beer they had been promised. “There was no shortage of things to console us.”

Anarchy ruled, said Duggan: those remaining decided to have a party. The Housetruckers Band played, turning the site “into Woodstock” for the few people there as workers or early arrivals. “Women’s band Cassandra’s Ears played well, by all accounts.”

While getting drunk, those on site started to realise the extent of the losses. “Things started to get really sickening, with finding out how much money people had invested in the food stands, equipment and all the other peripherals concerning the services needed for anything this large. The whole monster with a mind of its own was gaining momentum and was to tear its way through many people’s lives, leaving financial ruin and despondency.”

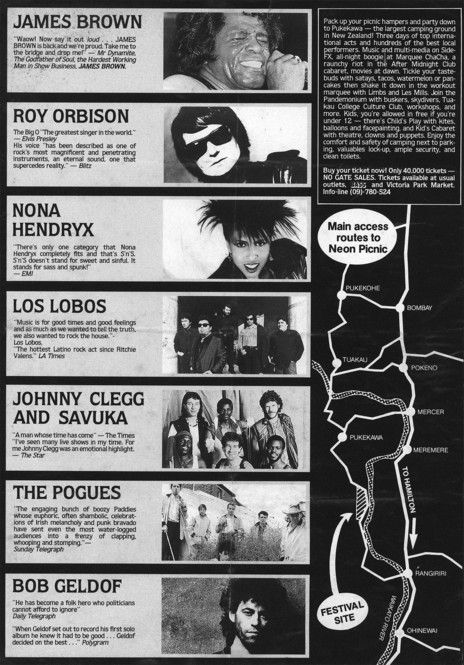

Reverse side of Neon Picnic A4 promotional flyer 1988, showing the international line up

The Neon Picnic’s demise received remarkably little coverage from the major papers, the NZ Herald, Auckland Star and the Auckland Sun, a short-lived tabloid. Perhaps because it was Anniversary Weekend they left it to radio and TVNZ to cover, reasoning that by Tuesday the readers would have moved on.

It was Richard Gordon, a young reporter for Metro, who did the investigative leg-work required to find out the reason for the festival’s collapse. In May 1988 Metro published “FIASCO” – a 14-page story of about 12,000 words.

“Because of a court suppression order in force,” Metro editor Warwick Roger fulminated in the introduction, illustrated by a rat, “important facts about one of the key people in the Neon Picnic fiasco – facts that could and should have been included in this story – have been necessarily eliminated. It is difficult to see how the public interest has been served by such a suppression order.”

Gordon’s article describes the increasing panic of the festival organisers as the weeks before the festival turned into days and then hours. It is a saga of extreme self-confidence combined with naivety. Bright yellow posters all over Auckland warned that tickets to the event were limited to 40,000 – in fact, sales were between 1000 and 2000.

Conceptual issues were at the core of the misadventure, explained Gordon. Mace was clear she didn’t want 17-20 year old males to be the core audience. Despite the upmarket advertising, there was an early 80s vibe of alternative lifestyle about the event.

(Ironically the week before Neon Picnic, Western Springs had been packed by a mainstream crowd of 60,000 for a Pink Floyd concert; above them floated an inflatable pig, whose snorting sounds went through the PA.)

“FIASCO” - Metro article by Richard Gordon, May 1988.

The Picnic organisers, Gordon wrote, “wanted ‘politically sound’ people to attend – not the strange brew of West Auckland ‘petrol-heads’ and Coromandel hippies who had dominated big festivals in the past. And so workshops were promised for picnickers interested in juggling, self-defence, massage, parenting, drama, spinning, weaving, writing and Niuean weaving. There were special facilities for those with physical disabilities. A marae was built on top of the hill above the site. A women’s space would provide a ‘safe, friendly place’ for women looking for relaxation, conversation and support services.”

All very much of its time – and ahead of its time – but the audience wasn’t interested. The idea that the Neon Picnic would be a more mature, inclusive Sweetwaters just didn’t get across and sell tickets.

No early warnings emerged that the festival was in trouble, but the directors of the company knew several months out that “they had a colossal problem on their hands”. Veteran promoter and city councillor Phil Warren was asked to look at the books and give advice. “He told them they should abandon the whole project” – advice which was ignored.

Two consultants came on board in the last few weeks. Tony Lipanovic, a budding entrepreneur, tried to bring in late investors by approaching high-risk speculators after the bank turned down an overdraft. Brian Richards, with a background in the music industry, tried to keep overseas acts on board. But money was needed for their air tickets – and everything else. The organisers were hundreds of thousands of dollars short of the capital they needed.

An indication of how desperate the Neon Picnic organisers were is that days before it was to start, the company secretary, Jonathan Blakeman got approval from American Express to put the airfares for the overseas acts on his credit card: $89,000. “Which tends to suggest,” wrote Gordon, “that Blakeman still had an extraordinary belief that the Picnic would come off.” That approval depended on a bank guarantee, which didn’t eventuate.

On the Wednesday before the curtain was to go up, Roy Orbison cancelled; by early Thursday afternoon Richards realised there was no money for the air tickets: “I couldn’t do any more to help. At 2.30pm I walked out.”

Spare a thought for the food stall-holders, who were calling the festival office wanting to know how many people to cater for, so they could buy enough perishable produce. Richards said one supplier was told to budget for 20,000 people, even though the organisers knew they had sold less than 2000 tickets at that point.

Lipanovic, meanwhile, had been renegotiating with the suppliers of portable toilets, lighting, staging and other services. The Sun reported that the Raglan Council was issuing an injunction against the festival because there were no portable toilets on site.

Gordon summarised the costs and income. The directors and original investors of Neon Picnic had put up $150,000 towards the event. To pay the acts, at least $344,000 was needed. (There is a claim in the story that all the overseas acts were paid in full, but not the air tickets to get them to New Zealand; Los Lobos said they didn’t receive a bean from the organisers.)

The total budgeted expenditure was $2.8m – but nothing like that money was ever received. Questions still remained about what was received – such as the $4000 each that 50 stall-holders were to pay in advance as rent (the potential total was $200,000) and the funds from early ticket sales. But, wrote Gordon, “No one knows who is owed what and who got paid. Roughly 150 creditors and 30 former staff with a total claim of around $500,000 were known to the Justice Department by mid-March.”

The AXEMEN on the site of the failed music festival Neon Picnic in January 1988. - Stuart Page collection

Undoubtedly, the inexperience of the two main organisers played a large part in the festival’s failure. Mace had worked at Nambassa, managed some small arts groups, and worked on an Oscar Peterson tour that was eventually cancelled. After time spent in student politics, Worth had been executive director of the Goftas, the chaotic New Zealand film and television award show in 1987, resigning just before it took place.

After the collapse, there was a lot of finger pointing. Mace “resolutely believed in some sort of conspiracy theory,” wrote Gordon. She said the music industry questioned her credibility and experience, and the media worked against them, that “there was a deliberate campaign to pull Neon Picnic down”. When asked why, she blamed sexism and the male egos in the music industry.

However, she could see the responsibility fell on her: “Initially I mortgaged my house, then I sold it, and whatever was left went into the company. It was a business risk. Let’s be cold-hearted about it – if anybody made a miscalculation it was me – I was handling the finances of the operation.”

When the Official Assignee gave his judgement to a public meeting a couple of months after the collapse, about 50 creditors turned up. They were owed money ranging from $1500 to $100,000. In total, creditors were owed $874,380, and Neon Picnic Ltd had assets of $49,000 ($37,000 of which was an expected GST refund).

Mace and Worth were bankrupt. Neon Picnic entered the music industry vocabulary as a fiasco, just as “sesqui” became a byword for event failure in Wellington two years later.

Daniel Keighley went to jail for crimes committed in the organisation of the revived Sweetwaters of 1999. His festival went ahead, though many acts and suppliers went unpaid. Mace and Worth’s festival only welcomed Bob Geldof at the arrivals gate, and also left many suppliers out of pocket. (Mace died of cancer in May 2011; she had been involved in setting up the Kingsland woollen crafts business Native Agent, and the Grey Lynn Farmer’s Market. Blakeman also died of cancer in November 2014, after a successful career in university financial management in Auckland and Sydney. Worth, his wife, became professor in public health and community medicine at UNSW, specialising in HIV research.)

Neon Picnic was an odd 80s mix of hippie romanticism and capitalist flash; the decade encouraged reckless speculation. Like the Chase Corporation towers that littered Queen Street, behind the mirror-glass façade the festival scaffolding was improvised and not fit for purpose.

--

Thanks to Richard Gordon