In January 1979, Los Angeles record producer Kim Fowley found himself stranded in Auckland on a one-man South Pacific honeymoon. He didn’t waste his time here either. In one week, Fowley recorded a Street Talk album and discovered The Crocodiles.

Fowley, who described himself as, "Part hustler, part talent spotter with studio skills", revealed the real reason for his New Zealand visit in a 2001 radio interview with Marty Duda. He had married in July 1978 but his wife had left him after only 68 days and he didn’t want to waste his cheap air tickets.

“I had an ill-fated marriage to an 18-year-old girl when I was 39 years old. I had honeymoon tickets that you buy six months early and you get a discount. There was no wife by the time December came around. I went on the honeymoon tickets, alone. I had a lovely time and New Zealand is my favourite country outside America.”

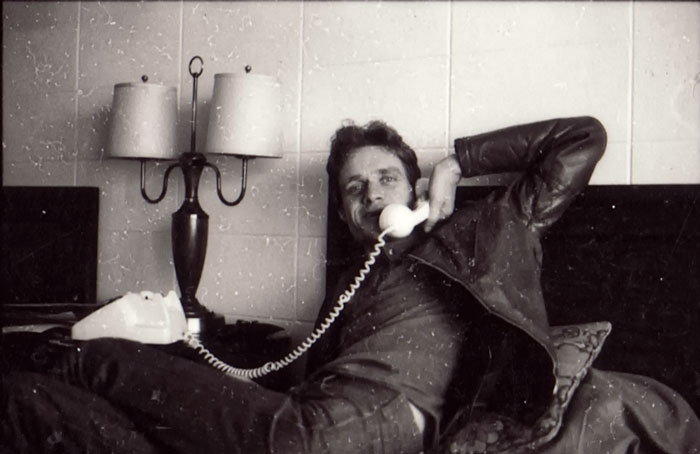

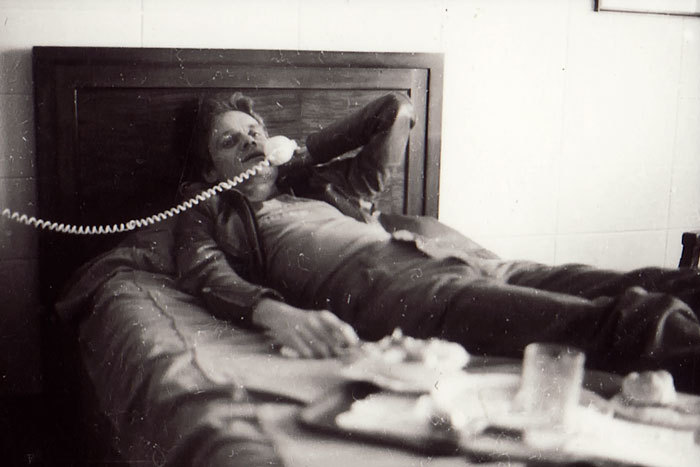

Kim Fowley in his Parnell motel room, 1979

Within 24 hours of his arrival in January 1979, Fowley found record stores, a local radio station, the local music magazine, a band to record, and he started to build his own fan base.

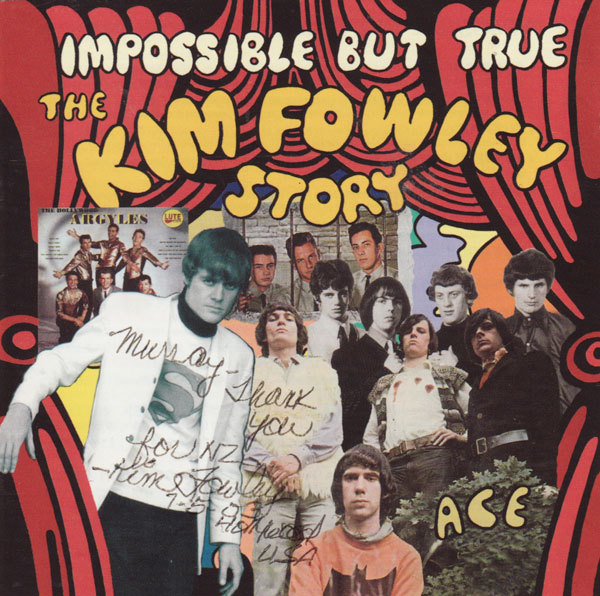

Being a train spotter music fan, I was star struck – Fowley's name was everywhere in 1960s Los Angeles as a writer, co-writer, co-publisher or producer – he is credited as producer on novelty hits including ‘Alley Oop’ by The Hollywood Argyles (1960 – No.1, Billboard Hot 100) and "wrote" ‘Nut Rocker’ by B. Bumble and the Stingers (a 1962 boogie-woogie based on a piece in Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker – No.1 UK Singles Chart, No.23 Billboard Hot 100). He even made it to England to contribute to the lyrics of ‘Portobello Road’ by Cat Stevens.

In the 1970s he co-wrote “King Of The Night Time World” and “Do You Love Me?” on Kiss’ Destroyer album (1976) and he produced and managed The Runaways, the all-female group who gave the music business the phrase “Big In Japan” and whose line-up included a young Joan Jett and Lita Ford.

The 2003 Impossible But True - The Kim Fowley Story CD autographed for the author. The 32 track album is filled with his pulp-pop records from the 1960s.

Fowley was the Energizer Bunny of the Sunset Strip, he never stopped working or talking.

Fowley was the Energizer Bunny of the Sunset Strip, he never stopped working or talking. Even while in a hospital bed in 2014, Fowley wrote songs with Ariel Pink, who played the 2015 Laneway Festival in Auckland.

I not only liked Fowley’s CV, I liked his intelligence and wit – he was a stand-up comic, motivational speaker, cultural psychologist, marketing guru, prolific lyricist and record producer all rolled into one. His IQ was through the roof and at six foot five inches he was also above regulation height for the standard 1970s New Zealand motel bed. In producer Glyn Tucker's words, “He was longer than the bed.” In many ways Fowley was in breach of our nation’s dour expectations.

Fowley maintained an on-going connection with New Zealand music. But as Glyn Tucker noted: “Kim Fowley was on the phone to New Zealand more than he was in New Zealand.”

When Fowley died (January 15, 2015, aged 75), Stuart Pearce, the former keyboard player in Street Talk, summed it up in one sentence on Facebook: “Kim kicked butt down here in 1979 with The Crocodiles and Street Talk albums both being made thanks to his interest and enthusiasm for NZ music.”

It has been written that Tim Murdoch, managing director of WEA Records (now Warner Music) had flown Fowley to our shores, but this was clearly not the case. When a letter was sent to all New Zealand record executives a month prior to Fowley’s arrival, Murdoch was the only executive who responded and wished to meet Fowley. But meeting the WEA boss was not easy – he was spending January north of Auckland at his Langs Beach holiday home.

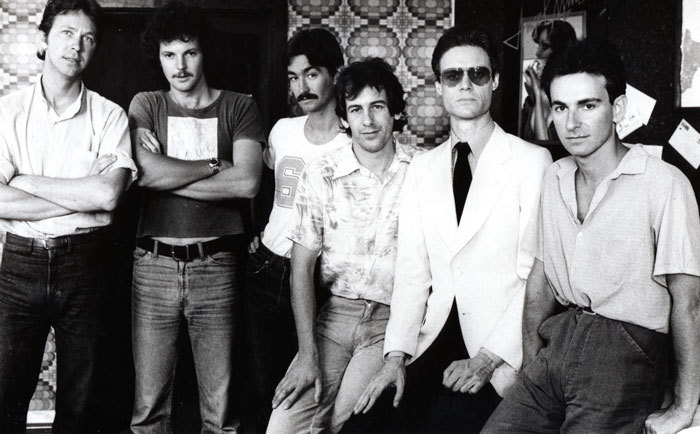

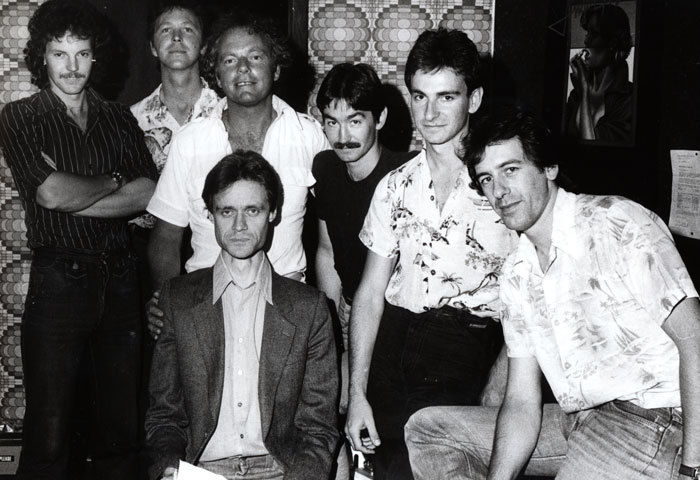

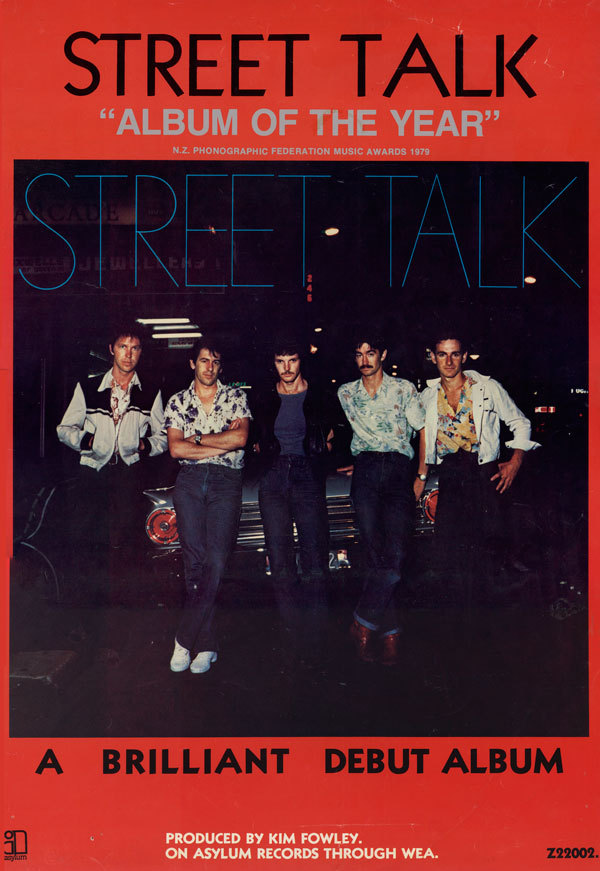

Street Talk with Kim Fowley at Mandrill Studios, 1979: Jim Lawrie, Stuart Pearce, Andy MacDonald, Hammond Gamble, Kim Fowley and Mike Caen

Fowley was only in Auckland for just over a week and participants in the recording sessions and hosting got very little sleep, so memories of his visit are sometimes hazy or missing in action. He’d been here only a few days when he collaborated with Street Talk and authored the lyric “stranded here in paradise, how can a poor boy break the ice?” which became the title of John Dix’s groundbreaking book on the history of New Zealand music, Stranded in Paradise.

He quickly understood the local psyche, telling Auckland Star writer Tony Potter (Monday Jan 22, 1979): “There’s a national inferiority complex that both New Zealand and Australia have because they have to go to America or England to be someone in the music industry. I’ve turned that around. New Zealand has the same population and cubic miles as Sweden and you speak better English than they do in ABBA country. Did you know ABBA do more business than Volvo? These guys [Street Talk] are going to be tax exiles in Stewart Island by next year. America or England isn’t better than New Zealand. New Zealand groups, after my visit here now, don’t have to go freezing in the winter of London, or choke in the smog of LA to make their worldwide records. They can do it here in sunny Parnell.”

On the phone – always. Kim Fowley spent large parts of his time in Auckland hustling on the phone, often calling contacts in the USA. WEA's phone bills must've been large.

Mandrill Studios

Former Mandrill Studios co-owner Glyn Tucker remembers the summer of 79 well, as he had the challenge of engineering the Street Talk recordings while Fowley presided over the process.

“I got a call just before Xmas 1978 from Wally Ransom of Southern Music, the only publishing company with an office in New Zealand,” Tucker recalled in 2015, “He said, ‘This big shot American producer is coming down here. Could I spend some time with him?’ Wally wasn’t going to be around, he was going to be on holiday.”

“Kim Fowley arrived just after New Year. He had a theory that The Beatles were discovered in a remote city and that New Zealand was a remote country where no music had been discovered before. I played him Mandrill recordings first – Citizen Band, Alastair Riddell, Waves, Rick Steele – and he didn’t like any of them. The only thing that caught his attention was the single ‘Leaving The Country’ by Street Talk, produced by Chris Hillman of The Byrds at Stebbing Studios. He really liked Hammond’s voice.”

That night, a Friday, Street Talk were playing at the Windsor Castle, 200 metres up Parnell road from Mandrill Studios, which was then located at 60 Parnell Road, on the corner of Earle Street. Tucker and Fowley went to see them perform. “They came back to the studio,” recalls Tucker. “Overnight they wrote ‘Street Music,’ completed pre-production on the band's songs and at 8.30am we all went home. Kim wrote a lot of the lyrics straight off the top of his head.”

Day One

On his first day in Auckland, Kim Fowley visited record retailers. Kerry O’Connor recalls, “He came into Record Warehouse and did the ‘I'm a big producer’ deity trick.” O’Connor played some local music to him, including Street Talk, and Fowley picked her brain on local music.

Fresh (enough) from The Runaways in the mid-70s, Fowley was known to be into the girl-thing because the guy-thing had been done, so girls were the future of rock and roll. Fowley was told about Zero, formerly of Suburban Reptiles. The group’s disintegration had been noted in Rip It Up (December 1978). In 1978 Zero had also toured New Zealand with The Rocky Horror Show starring Gary Glitter.

Fowley found Simon Grigg at Professor Longhair’s Record Shop in Parnell Village, a kilometre up the road from the his motel. “I was standing in the store and this somewhat unique looking tall man appeared in front of the counter,” recalled Grigg. “He was wearing cowboy boots, which were rather unusual on a quiet Parnell morning. Kim, without a word of introduction, asked ‘where do I find Zero?’

“I knew where she was (at the flat) and I knew who he was but I asked him, ‘Who’s asking and why?’ ‘Kim Fowley, and I’d like to meet her’ he said, or words to that effect. I told him I’d pass the message on and he gave his contact as a room at the motel on Parnell rise. I tried to engage him in some music conversation but he was instantly disinterested and left.”

“Simon fielded it for me,” Zero said in 2015, “I never met Fowley. In a slightly cavalier gesture, Simon blocked a meeting. I don't know whether he wanted to protect my maidenly pureness or didn’t want to lose me from the band.”

Radio One Zee Em

Fowley spoke of his 1ZM visit to the Auckland Star (Monday Jan 22, 1979): “I’m at Radio One Zee Em and they play me a hundred New Zealand groups – well, it seemed like a hundred, and immediately a group called Street Talk came on it hit my ear. It smelt like money.”

In 1979 Peter Fyers was the 1ZM programmer. He produced recordings of local bands in the NZBC Auckland studio at Broadcasting House, Durham Lane for several on-air programmes. 1ZM had recently recorded Hello Sailor, Street Talk and Th’ Dudes, and the station had broadcast early versions of Hello Sailor’s ‘Gutter Black’ and ‘Lying In The Sand’, Street Talk’s ‘Leaving The Country’ and Th’ Dudes’ ‘Be Mine Tonight’ and ‘Right First Time’. The station had also recorded Street Talk doing great versions of Cream’s ‘Badge’ and Albert King’s ‘Born Under A Bad Sign’.

“Early one evening, I got a call to say Kim Fowley was in town,” recalled Peter Fyers in 2015. “He had heard that I had been recording local artists. He was looking for the ‘new Beatles’. I said, ‘Ok, it’s getting late, what about coming in tomorrow?’ ‘No, he wants to hear them now’ was the reply. So I phoned Paul Streekstra, who was one of the young recording engineers who had worked on several of the recent sessions, and asked if he would come back to work, to help. There were a lot of tapes and a lot to rewind. Fowley arrived and he wanted to hear everything we had.”

“About 2am, he made his choice and demanded, ‘Get me this guy on the phone.’ I knew Hammond Gamble pretty well at that time and I could see Fowley was running hot. I had Hammond’s number and so said, ‘I’ll ring him’ and I picked up the phone. Hammond’s wife Sue answered the phone, ‘Very sorry to ring you at this hour Sue, but I need to talk to Hammond.’ Sue woke Hammond up. ‘Hi Hammond, it’s Peter Fyers here, I’m in the studio with an American record producer named Kim Fowley, he wants to offer you a record deal.’ Hammond sounded pretty groggy, but said, ‘Uh, okay, hold on, better get myself a cigarette.’”

Hammond Gamble does not remember the call, but Bryan Staff was also at 1ZM that night, doing his 7pm to midnight show and he remembers the early morning phone call to Hammond. Fowley must have visited 1ZM on the Thursday night prior to his showing up at the Windsor Castle with Glyn Tucker.

At the time, Rip It Up was into the many young punk and new wave bands playing at local venues. I wanted to show Kim the underbelly of local music, but I wanted to be a bit posh, so I discarded my Morris 1000 and borrowed my father’s Ford Escort to take him to see what was happening on the Saturday, the day after he met Street Talk. Marching Girls were in Melbourne and Toy Love were nowhere to be seen, so I took him to see several bands, including Johnny and the Hookers.

Street Talk at Mandrill Studios, Parnell, with Kim Fowley and WEA Record's Tim Murdoch: Stuart Pearce, Jim Lawrie, Tim Murdoch, Kim Fowley (front), Andy MacDonald, Mike Caen and Hammond Gamble

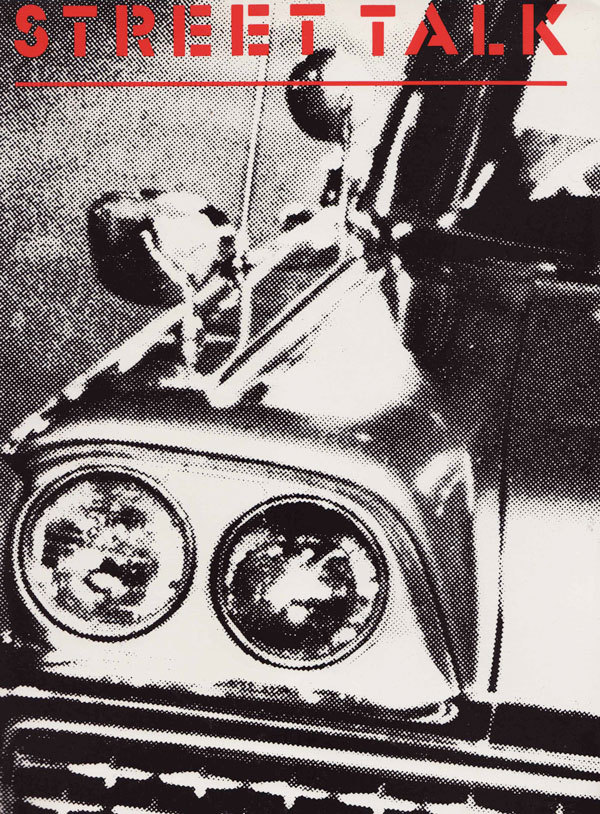

WEA employee Terence Hogan, who did promotional and in-house design work for the company, sat in on the Street Talk recording sessions. He designed the cover and promotional artwork for Street Talk’s debut album. At the time, I was doing an ongoing series of V8 cars in Queen Street, so I took a photo of the band in Queen Street for the album cover. Hogan used some of my V8 car series in promotional material as the images fitted in with the Americana vibe of the song, ‘Street Music’.

Hogan recalls Fowley’s comments on seeing Johnny and the Hookers. “He said that they were good but that the world just didn’t need another Dr Feelgood, which I thought was a bit off the mark as a comparison.”

The need for speed

Street Talk were smart enough to recognise a great opportunity – the guy worked fast and they would get an album fast! Hammond Gamble did not mind the pace. “We were playing six nights a week in those days. We were pretty onto it. I had four songs written and Mike Caen had two.”

Speed was always a virtue for Kim Fowley. In praising his own hasty habits he felt obliged to compare himself to legendary producers. “Very fast. Very Sam Phillips and George Martin.” (2012, Rock Cellar Magazine.com)

“Glyn was getting a bit stressed,” said Gamble in 2015. “When we were there at 4am in the morning, he’d say ‘I think we’ll call it a day now’ [but Kim would say] ‘No we’ll keep going.’ I kept going on Steinlagers. I used to hide them behind the desk in the front room so Fowley wouldn’t see them.”

“I liked the fact that he worked fast and did not spend hours in the studio on an insignificant technicality,” Tucker told AudioCulture in 2015. “I wanted to go a little bit slower but that nervous energy he created, added something, that worked.”

“He looked at the big picture. He came from a song point-of-view. I don’t recall him even being interested in the technical gear. He did talk to me about getting more bottom end and we were in danger of overloading the bottom end. Kim produced from the heart and not from the technical perspective.

“He was a hard taskmaster, starting at 3 or 4pm at the earliest and working until we dropped," said Tucker. After finishing as late as 8am, Tucker would get two hours sleep and then return to the studio to earn a living doing commercials all day.

“I do not know what the WEA deal with Kim was,” said Tucker, “but I got the okay from Tim to proceed and cut a couple of tracks. I don’t think Tim was expecting an album.”

Mandrill delivered an album for approximately $6,000 and Glyn quickly cut the vinyl master for the album at EMI in Lower Hutt. In the January 27, 1979 issue of US Billboard magazine, local correspondent Phil Gifford quotes Fowley: “Because of the professionalism of Street Talk and Mandrill, we’ll bring in the finished album for under $10,000, with a world class sound.”

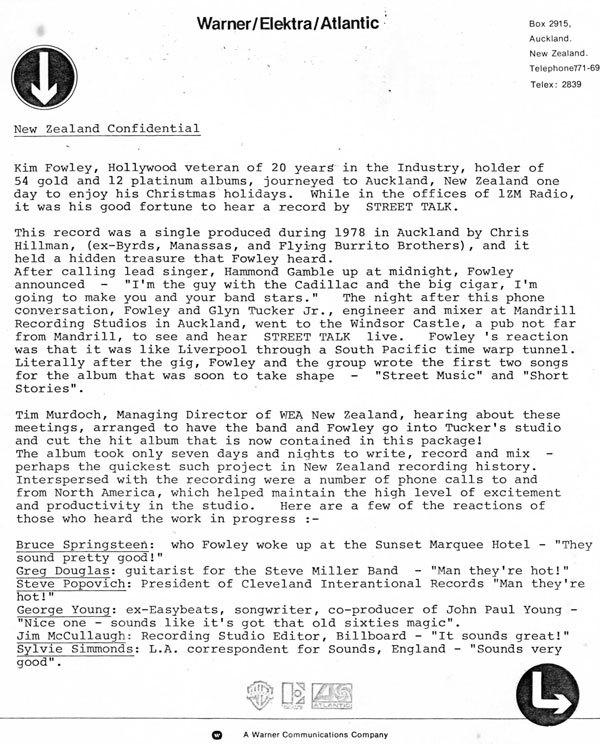

Kim Fowley's New Zealand issued bio

Lyrics

One of the prime hustles of recording music is the producer contributing to the songwriting as a way of getting a share of the lucrative songwriting royalties. In 2001, I asked Glyn Tucker whether he thought it was fair that Fowley set out to contribute the lyrics to the sessions. “It was the way he worked because he made most of his money out of music publishing,” replied Tucker. “If it hadn’t been for Kim, Street Talk would not have had a strong single on the album because ‘Street Music’ would not have been written.”

In 2015, Hammond Gamble spoke to AudioCulture about their writing collaboration: “He didn’t really have anything to do with the melody and the music. He was like a bloody headmaster, funny but a bit scary. He was really funny! He was always bangin’ on about sex – and I’ve always been a bit prudish – he sounded like a bloody animal. That doesn’t take away anything from his capability. He really had good ears and he knew what he was doing and he knew how to get it happening quickly. He quite enjoyed working with people who were younger and impressed.”

With the album already in the stores Hammond Gamble spoke to Rip It Up writer John Malloy about working with Fowley: “He’s just an incredible producer. He’s light years ahead of anybody I have ever been associated with. He really did some amazing things with us as far as getting us to work at speed. He has an incredible ear. Glyn Tucker engineered it all really well, while Kim sort of directed, arranged and produced the whole thing – and promoted it.” (Rip It Up March 1979)

Bassist Andy MacDonald told Rip It Up: “He’s quite capable of having his mind on two or three things at once. He’d be listening and jotting down lyrics … to fit the tunes. The studio is his thing. He thrives in it.”

Hammond described Fowley’s songwriting role: “Kim either patched up lyrics and wrote whole verses, or he wrote the whole lot, so what we did was put music to his lyrics, with his direction.”

Rip It Up writer (and musician) John Malloy saw the importance of the album at that time – when very few recordings were being made. He described the album as, “a milestone in New Zealand recording history in that it has the full backing of a record company with international connections. That it takes an LA producer to bring this about is less important than the fact this is happening.”

Studio time

Back to WEA employee Terence Hogan, who was a longtime music fan and had written for Hot Licks and Rip It Up. He did amazing poster artwork for punk gigs and he was already aware of the legend of Kim Fowley.

In 2015 Hogan recalled, “I went down there immediately after work on the first night and stayed on until the early hours of the morning. I did the same for all the sessions over the next few nights. It was fascinating watching Fowley work as a producer. It wasn’t done so much on a technical level but more intuitively, with a lot of referencing to other bands and musicians to try and get the sound he wanted.”

“Fowley was very smart and had a great recall for all the names he had worked with or crossed paths with over the years. So this extensive and colourful personal history underpinned his many pronouncements on the world of rock and roll. In amongst all the broad generalisations and assertions there were some bluntly irreverent and amusing anecdotes from behind the scenes.”

Initially, Fowley was a bit wary towards Hogan. In response to an innocuous question about producing, “Kim turned to Glyn and said, ‘I think Murdoch’s got Terry down here to keep an eye on me’. He then turned to me with a thin smile waiting for my response. I was able to tell him the truth, that Tim Murdoch didn’t know that I was spending all night at the studio and all day at WEA trying to do my job while half asleep. I said that I hadn’t had the chance to see this process right through before and I was just soaking it up for my own benefit and enjoyment. He responded to that very positively, and I think that amongst all the bluster Fowley was also a genuine fan of the music and if he trusted you he would drop some of the pushiness, the need to be ‘Kim Fowley’ all the time. Things went pretty smoothly from then on and it was mostly a really enjoyable and funny experience.”

Realising that Hogan would look after aspects of the project (cover art, etc.) once he left town, Fowley met him at his Parnell motel before the day’s recording started. “At these morning meetings,” said Hogan, “we would sit on the floor where he had his papers spread out around him and he would go through his notes about all the people that needed to be sent copies of the album when it came out, who needed to be in the credits and various other bits of business.”

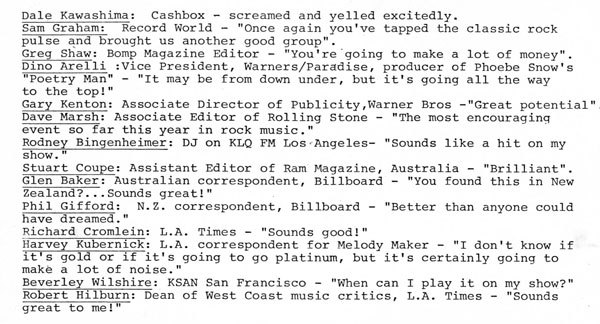

The quotes from "names' continue ...

Fowley became agitated that Tim Murdoch was a no-show at the sessions. According to Hogan, Fowley’s complaint went something like this: “I’m working my butt off for peanuts to launch the South Pacific Bruce Springsteen on the world, and Tim Murdoch won’t leave the beach to come down for five minutes and hear what’s going on!” The LA producer then made vague threats about talking to people back in the US about this situation in ways that, he suggested, Tim Murdoch might find embarrassing.

“I think that Tim had intended to come in at some stage,” says Hogan, “but this was the stroppiest I’d seen Fowley; so I relayed all this to the WEA office, stressing a bit of urgency while not passing on a couple of the more pointed details of Fowley’s threat.” Eventually the message got to Murdoch who made his way back to the city.

“Tim actually came to Mandrill for a few minutes at the end of things. I have a memory of us all standing in the foyer and there being lots of bonhomie and enthusiasm between Tim and Kim.”

When WEA International used photos of their managing directors around the globe in Billboard magazine, Tim Murdoch was pictured holding up two crayfish. Fowley may have been familiar with this image as he got Murdoch to record a promotional audio that in essence said, “I’ve just rushed back from lobster fishing on the beautiful NZ coast to hear the tapes of this terrific new album that Kim Fowley is recording with Street Talk.”

The Hype

As if Glyn Tucker, the studio owner/ engineer etc, didn’t have enough to do – Fowley also wanted to sell the album while he was recording it.

“I learned a lot about the American hype industry,” Glyn Tucker told me in 2001. “On the second day he got on the phone hyping the record to the American music industry. He was ringing people like Bruce Springsteen. He got these guys on the phone and said, ‘I’m in New Zealand and I think I’ve got the next Beatles.’ ”

The cover of the Street Talk PR folder which included the Kim Fowley bio seen above, the image is taken from the author's V8 shots in Auckland in the 1970s.

On the back of the Street Talk album cover, some of the people that Fowley called were thanked as “The Telephone Gang”: Rodney Bingenheimer (Pasadena’s KROQ-FM), Robert Hilburn (LA Times), Harvey Kubernik (MCA), Dave Marsh (Rolling Stone), Dale Kawashima (Billboard), Greg Shaw (Bomp!), Beverly Wilshire (San Francisco’s KSAN-FM), Dino Airali (Paradise Records) and Australian writers Glenn A. Baker and Stuart Coupe. According to Billboard he also called Phil Spector and Steve Popovich (Cleveland International Records).

Tucker learnt how to use a recording desk as a promotional tool – when asked to – he would roll the multi-track tape for the audience of one on the other end of the phone – “doing a mix on the fly to make it sound half-decent.”

One of these phone calls to US rock royalty was timed to take place when I visited the studio, to impress the gullible editor of Rip It Up. I was not the only writer to be impressed. University of Auckland music lecturer William Dart described Fowley as “a walking definition of American affability” in Rip It Up (February 1979).

When I took a “portrait” of Kim Fowley, he looked positively presidential. He was in awe of the fact that I was in awe of him. I am not a portrait photographer, I am a documentary photographer, but Fowley only did portraits!

Fowley liked music journalists visiting the studio. He liked to hold court. In 2015, Mandrill’s Dave Hurley said, “I remember he devoured chicken seated on the floor of the studio during a press conference – bones flyin’ everywhere!”

Fowley tailored his story to push the right buttons for his audience. He must have thought Phil Gifford (Billboard) was a soul man as he described Mandrill Studios as a “Muscle Shoals-type operation … like the good old days when people like Jerry Wexler and Leonard Chess went into the Deep South to produce singers like Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin.” (January 27, 1979)

The street poster for Street Talk's debut album, produced by Kim Fowley

The Crocodiles

As Glyn Tucker recorded The Crocodiles, you could ask the question – What’s Kim got to do with it?

When interviewed by Marty Duda in 2001, Fowley abridged his role into one fictional day: “On my last day in Auckland I found in the trash bin – behind where we were sitting in the studio – a tape by the group The Crocodiles. I spotted that group and declared it God and said to my engineer, the legend – Glyn Tucker – owner and founder of Mandrill Studios. Glyn is like George Martin. I said, ‘You produce this band. So I gave birth to them. I take credit for being the consulting physician. Glyn was able to produce it. I was in the country for eight days and I won five NZ Music Awards.”

The truth is less dramatic – Fowley worked with The Crocodiles over several days. Terence Hogan invited his friend Arthur Baysting to Mandrill to observe Fowley working with Street Talk. Baysting took along a cassette of Spats and played Fowley some songs.

“He heard two things that he liked,” Baysting recalled to AudioCulture in 2015, “One was ‘New Wave Goodbye’. The energy of it made Kim sit up. The other was Tony Backhouse’s great Beatles vocal harmonies, especially on ‘Young Ladies In Hot Cars’. At Kim’s insistence I immediately rang Fane at Waimarama [Hawkes Bay] and told him to get up to Auckland. He hitchhiked up next morning. I also spoke to Tony and he flew up.”

With the Mandrill Studio busy, Fowley was observed sitting with Fane Flaws and Tony Backhouse on the grass slope of Fraser Park, across the road from the studio – while they played their songs on acoustic guitars.

“He wanted to hear all our songs,” recalled Fane Flaws (2015), “so we made Peter Dasent fly up and we played him 32 original songs from which he selected an album’s worth. If he didn't like a song he would just say ‘next’ halfway through it – or ‘Billie Holiday would not sing this song if she was alive today’. He also gave us some lyrics – which we didn't particularly relate to – it was implicit that if he organised for us to record he expected some songs on the album. ‘Ribbons of Steel’ made it by default. There was a lesbian one called ‘Martha And Mary And The Buried Treasure’ and another I can't recall. We wrote three uninspired songs with him.”

“The best thing was a day where he talked for about twelve hours non-stop, telling us about all the great people he'd recorded or hung out with and he told us how the American music industry worked, how payola works. He told us how he had killed a guy who attacked him in a bar – ‘these hands are registered lethal weapons!’ It was a great, intense day.”

“He told us we had to change our name cos there was a disco band in the states called Spats,” Flaws recalled. “He wanted to call us Insect. We told him we already had a couple of alter egos, one of which was The Crocodiles and we liked that. He always called us Crocodile.”

Fane Flaws recalled Fowley saying that he would get them a recording contract: “I will put on my twelve hundred dollar Armani suit and walk into John McCready’s office at CBS and say, ‘Kim Fowley – 54 gold, 12 platinum at your service’ – and he will offer to sign your band.”

When it came time for Fowley to leave town, Baysting drove him to the airport. The producer must have called McCready – as en route to catch his plane – he chided the CBS executive for saying: “I have already heard their demo, I don’t need to hear anymore.”

Fowley was unaware of how the guys formerly known as Spats would soon evolve. “This group has the chance to be the new 10cc,” he told Arthur Baysting.

Spats had the potential to be the next 10cc, said Fowley.

There was a gap of several weeks before recording the album with Glyn Tucker, so Fane Flaws and Arthur Baysting and partners headed south to Tiromoana at Fox River, north of Punakaiki to write songs for the album.

“Our Tiromoana communal hideaway was the best place I knew to get songs (and still is),” said Baysting. “Fane had a start to ‘Tears’ and we finished that plus quite a few others. If it wasn’t for Fowley I would never have written ‘Tears’ with Fane – and that was what made me take songwriting seriously. It was because of ‘Tears’ that all the music stuff followed with APRA, the Green Ribbon push etc.”

Baysting noted that “all through the Mandrill sessions Fowley kept looking at me and saying ‘Manager!’ – I did this unwillingly until the album came out. Fane persuaded Jenny Morris to join. I disapproved because I loved the Wide Mouthed Frogs and I knew it would split that group. Jenny was incredibly loyal to them but within a couple of rehearsals I knew she made the band great.”

Largely due to Fowley’s enthusiasm, Glyn Tucker took on the Crocodiles project. When he travelled to Wellington to record the rhythm tracks for The Crocodiles’ album, Tucker did not view the band as “mainstream” although their songs did have hooks. He was in for a surprise as when he arrived at the Radio New Zealand studio in Broadcasting House, he learnt the band had a new singer and a new song to track. “You could tell ‘Tears’ was a hit, even before we recorded it,” said Tucker.

It was left to Tucker to find a record release for The Crocodiles. He had a deal for the Mandrill label via Phonogram but they “did not like” the album, so he went to RCA and they “loved it”.

When they were promoting The Crocodiles’ debut album, Dasent spoke of Fowley’s inspirational role: “I suppose it was partly the fact that he was an American and kept talking about international release and partly because he was so positive about everything, he gave us a taste of energy and that’s still with us. He was saying, ‘Look it’s all possible, you don’t have to have a New Zealand inferiority complex’.” (Rip It Up, April 1980)

Flaws recalled their 1979 mistake: “Fowley also introduced us to Wally Ransom who encouraged us to sign a terrible publishing deal with Southern Music which I believe Fowley had a slice of. We were so ignorant we signed a 50/50 deal with Southern for Australasia. When the record came out in Europe – Southern Music World Wide took 50% then Southern Music Australasia took 50% of the remainder so Arthur and I ended up with 12.5 % each for ‘Tears’. A pitfall Fowley failed to mention. I liked the guy.” At a later date terms for the writers were renegotiated with Southern.

Phone Tag

In the following years, Fowley was constantly on the phone to people he had met in Auckland. I used to get entertaining calls from Kim, usually when I was on a Rip It Up deadline. One call was about the 1980 Industrials album that he produced and co-wrote, while another call was from New Orleans, a port city that he probably compared to Liverpool.

Mike Chunn recalled in 2015, “It must have been 1980 when he rang all the time – only about Pop Mechanix. It was the ‘Now’ single that he had. He kept going on about them being the next Beatles. I never met him. I think he just loved that song.”

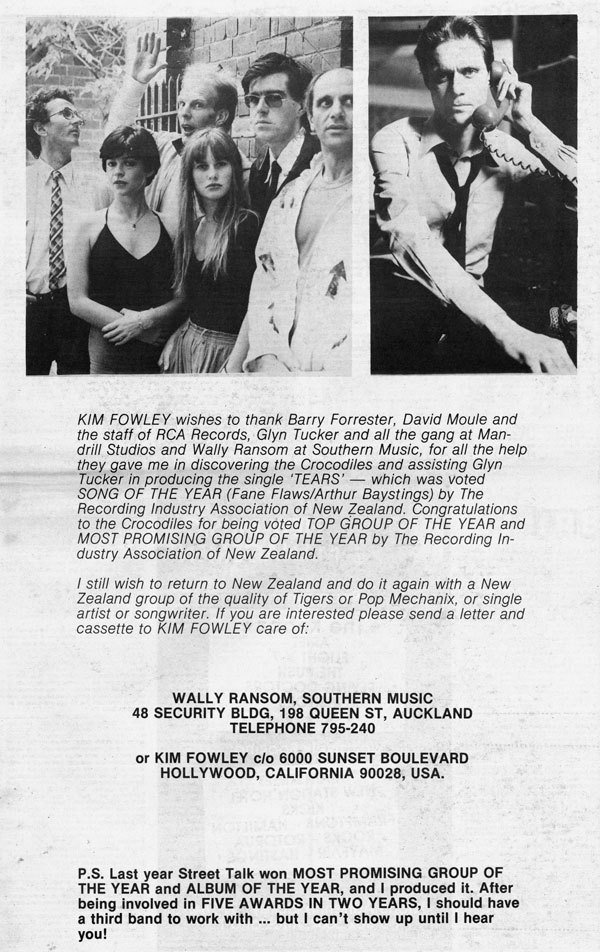

A year after his visit, Kim Fowley placed two full-page adverts in Rip It Up magazine (June and December) boasting of his role in discovering The Crocodiles and “assisting Glyn Tucker in producing the single ‘Tears’, which was voted Song Of The Year by The Recording Industry Association of New Zealand.” The December advert also read: “I still wish to return to New Zealand and do it again with a New Zealand Group of the quality of Tigers or Pop Mechanix, or single artist or songwriter” and supplied an address to send a letter and a cassette tape.

Kim Fowley's full page advert in the December 1980 Rip It Up

These adverts had a secondary message – Kim Fowley was clearly available to do paid work in New Zealand. But there were no takers. In the 1980s the multinational records labels spent a pittance on local A&R, often choosing to distribute local indie labels as their only commitment to New Zealand music.

When OMC’s ‘How Bizarre’ was No.1 in the USA in 1997, Fowley got on the phone to Simon Grigg at Huh! Records.

“He asked me if I had any more ‘mawrie’ bands, ‘especially girls’,” said Grigg. “We talked for about thirty minutes with him grilling me about who was hot in South Auckland. Eventually I gave him Phil Fuemana’s phone number at Urban Pasifika Records. He never rang Phil.”

When their debut album was released in February 1979, Street Talk were self-managed with help from WEA and Kim Fowley. Hammond Gamble spent nights on the phone with Fowley and his lawyer trying to make an arrangement for the band to work in the USA. Fowley said that “he needed power of attorney” – whereas Gamble wanted the band to have the final say.

Fowley helped to achieve foreign releases for the Street Talk and Crocodiles albums.

“The idea was we were going to go to the States and work our arses off for fuck all,” recalled Gamble, “I had to say in the end that it was not going to work.”

Fowley helped to achieve foreign releases for the Street Talk and Crocodiles albums. But without either of the bands present in those territories the releases were ineffectual.

Street Talk started 1980 with a new manager, Cook Street Market entrepreneur Brian Jones. In February he visited Los Angeles and got an enthusiastic response from WEA International A&R executive Dan Loggins, inspiring the band to write for their second album.

A year after the release of their debut album, Street Talk had moved on and were only doing three songs from that album and were recording their second album Battle Ground Of Fun at Mandrill Studios with Bruce Lynch producing.

John Dix wrote about their second album in Rip It Up (May 1980) and explained Kim Fowley’s absence from the project. Their manager Brian Jones severed ties, “when after listening to the demos the band had sent, Fowley wanted them to use his specially written lyrics. Brian, quite rightly so, said he didn’t think that was in the band’s best interests.”

Glyn Tucker visited Kim Fowley in Los Angeles, about 1982 and sat in at a Sunset Boulevard studio. “He was disinterested in the project, it was totally different from what he was doing with Street Talk.”

At a later date, Fowley suggested, via Glyn Tucker, that Hammond Gamble write melodies to Fowley’s lyrics with the aim of placing the songs with US recording artists. “He gave me a whole pile of lyrics,” said Gamble, “and I spent a whole lot of time on the songs.”

When no response was forthcoming from Fowley, “I asked Glyn what Kim thought of them? ‘Glyn replied, ‘He thinks they’re shit’.” In 2015, Gamble reflected on the melodies – “they were a bit complicated and Kim’s a bit of a four on the floor sort of guy.”

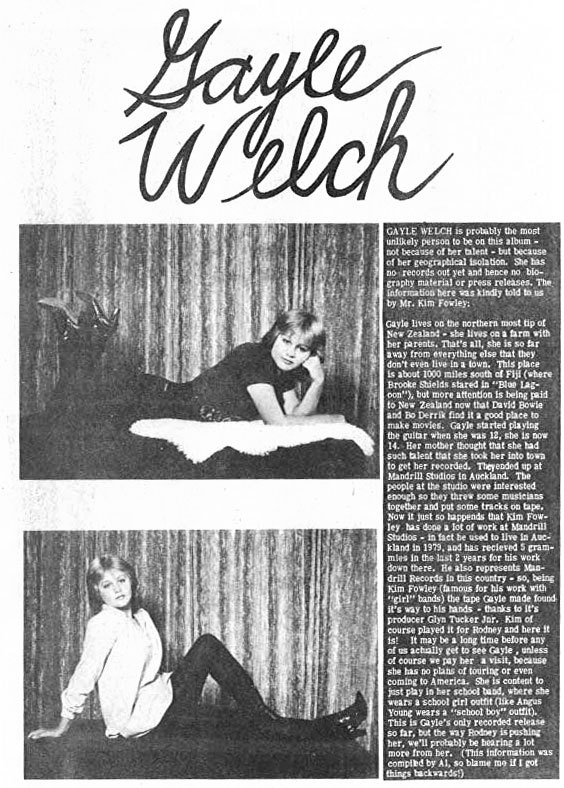

Gayle Welch

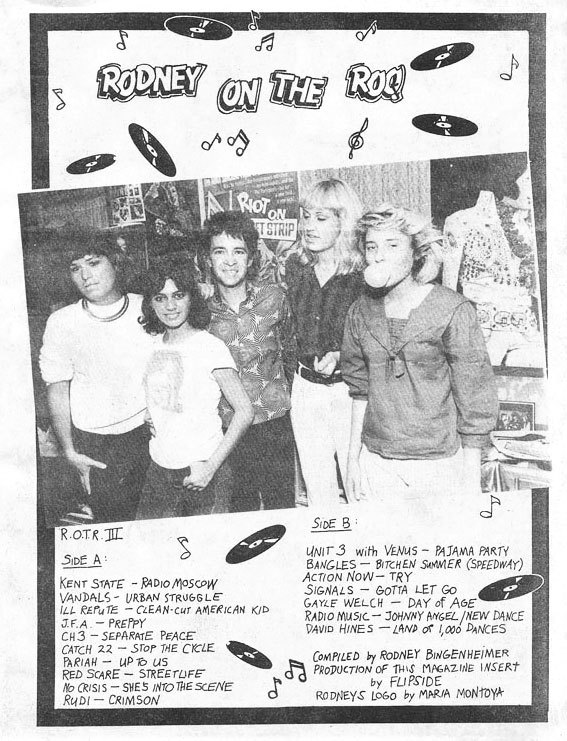

Glyn Tucker played a demo by a 14 year-old Northland singer Gayle Welch to Fowley and he encouraged Glyn to record her song as a single. In 1981 visiting Chicago guitarist Bill Millay produced the track ‘Day Of Age’. Los Angeles DJ (and Fowley’s friend) Rodney Bingenheimer loved it and selected it for his 1982 punk/ new wave compilation – Rodney On The ROQ Vol. III on indie label Posh Boy Records. The 17 track LP included early Bangles track ‘Bichen Summer’ and ‘Urban Struggle’ by The Vandals.

14 year old Northland singer Gayle Welch appeared on influential LA radio DJ Rodney Bingenheimer's 1982 compilation Rodney On The ROQ Vol. III after being 'discovered' by Kim Fowley

In a zine story (Flipside #35) on the album, Fowley said, “Gayle lives on the Northern most tip of New Zealand – she lives on a farm with her parents. Gayle started playing guitar when she was 12 and she is now 14. Her mother thought she had so much talent that she took her into town to get her recorded.” The zine also says that Fowley “used to live in Auckland in 1979 and has received five Grammies in the last two years for his work down there.” (Either Fowley took the liberty of translating the NZ “Tui” Awards into US “Grammy” Awards or possibly the writer made the mistake.)

‘Day Of Age’ had a catchy new wave strut and a lyric that she wrote all by herself – “I’m just a school girl, although he’s looked my way … but it’s going to take a while, to reach my day of age.”

Flipside said there were no plans to tour or visit the USA: “She is just content to play in her school band, where she wears a school girl outfit (like Angus Young wears a school boy outfit).”

A bio for Northland singer Gayle Welch as it appeared in US magazine Flipside #35 in 1982. Welch would go on to be part of Kim Fowley's 2nd Runaways in the mid-80s.

Bill Millay returned to Auckland in 1984 and contributed arrangement ideas and BVs to The Mockers’ ‘Forever Tuesday Morning’. Millay fell in love with Gayle Welch and they returned to the USA together and got married.

In 1984 Fowley created a new Runaways, as he owned the name. He produced the album and built the new group’s image around the teenage Gayle Welch although Missy Bonilla sang most of the lead vocals. Bonilla claims that Welch only sang lead on ‘I Want To Run With the Bad Boys’ – a track with a very Fowley-style lyric. The album, The Young And The Fast was released on the Allegiance label in 1985 and there was no ‘Cherry Bomb’ on the record – it was just a bomb.

Bill Millay played guitar on the sessions and says on his website, “If you are a Runaways fan and are upset by ‘the new Runaways’, please don't blame me, I always thought they should have used a different name.”

The album cover read – “The Runaways” – there was no “New” in the group’s name. The album has been described as a cash-in, but there was not likely to be any cash in a low-budget recording (they used a drum machine), seemingly designed to piss off the original Runaways, rather than to launch a new group.

According to Bill Millay’s website, his then-wife Gayle Welch recorded a second album with the new Runaways. The album was called I Was a Teenage Runaway and was only released in Japan.

The Viper Room

When NZ band Rubicon did a showcase at The Viper Room in Los Angeles in July 2003, the LA organisers Michelle Bakker and Amine Ramer told me that Kim Fowley was excited that I’d made it to LA and that he’d given them a page of names and numbers for me to call and invite to the performance. I was not in the mood for the task, but fortunately band member Paul Reid volunteered to make the calls as manager, saying, “Kim Fowley gave me your number to invite you to the showcase by the New Zealand band Rubicon …” It was the fourth of July weekend, but only two call recipients were pissed off about getting a call. When Paul called one of the numbers scrawled on the sheet, it was Kim who answered and listened to the spiel before saying, “I am Kim Fowley and you’re a fuckwit!”

Anyway, Paul’s calls worked well, and not only was Kim there (with his chauffeur and limo) but several of his music business colleagues attended. When local music biz magazine Music Connection wanted to take a Rubicon photo, I suggested including Kim, but clearly the photographer wanted anyone but Kim in the photo. Clearly Mr Fowley had been in too many Sunset Strip photos over the years.

![]()

Kim Fowley with Rubicon at Hollywood's Viper Room, 2003

The next day we arranged to visit Kim at his modest home in Redlands, en route to Las Vegas. What was meant to be a brief visit went on and on. When a hapless indie label guy phoned Kim about progress on a project, Kim played Rubicon down the phone line to him and then compared Rubicon signing to the indie guy’s label, to Nirvana signing to Sub Pop. This was getting a bit too much for me and I wanted to drive in daylight. We did not get free of Kim until dusk.

“He was unwilling to let us leave ... it was like that scene in Terminator.”

– Nich Cunningham

Soundman Nich Cunningham recalled the day. “He seemed to have no furniture in his house, just a ton of gold records and cassettes leaning against the walls of his living room. He was unwilling to let us leave and when we finally got in the car, it was like that scene in Terminator as he appeared to pursue us down the street. It was a great experience.”

The Runaways Movie

Kim Fowley was always going to LOVE the Runaways movie – even though he was not invited to the set (“because I’m a disruptive human being”) – as he wanted to make loads of money as co-writer and publisher of the group’s songs. He must have jumped for joy when he heard that a top actor, Michael Shannon (Boardwalk Empire, Man of Steel) would play Fowley – “I was terrified that Carrot Top was going to play me.”

Although Shannon is not a pop culture person or a Californian, he summed up the music man well in the movie’s YouTube promo interview: “I’d never claim to be an expert on Kim Fowley, but as far as I have been able to ascertain he is largely motivated by a love of music. An amazing amount of creativity has come out of this person.”

When Fowley was interviewed for the movie promo, he had prepared a stilted one-liner: “Michael Shannon is the new Christopher Walken and he lived up to his potential by delivering the performance of a lifetime.”

The interviewer ran out of questions for Fowley after a few minutes. Fowley then improvised his own questions; he liked to talk. When he was interviewed by Marty Duda in 2001, after one hour and 10 minutes on the phone, Duda tried to conclude the interview, Fowley protested, “Come on, you didn’t give me any time.” So he got some more time and he made it clear that he was looking for employment opportunities in New Zealand radio, television or universities.

Fowley had fond memories of New Zealand and when he autographed a CD for me in 2003, he scrawled a reference to the “Summer of 79” as though it was the name of a hit record. It was a hit memory for him and in his own YouTube video, titled ‘Garbage Man in a Vinyl Wonderland’, Fowley was asked to name the best record he ever made. His answer was “Best record? Street Talk, New Zealand on Warner Brothers.” Later in the video he is asked for one-liners while holding covers and for Street Talk he comes up with the glib “Dire Straits meet The Boss of New Zealand” – demeaning his own achievement as a producer.

Despite his numerous encounters with cancer, Fowley was always busy. He was a guest raconteur at Tony Wilson’s “In The City” music conference in Manchester in 2003. Prolific (and grumpy) music business blogger Bob Lefsetz was also there and noted, “I was sitting next to him in a restaurant. He was tall. He looked like a cross between Richard Kiel and Frankenstein. He was imposing. But up close and personal ... I wouldn't exactly say he was a pussycat, but he was engaging, he didn't boast, but if you asked him questions he was glad to wax rhapsodic and add to the myth. But underneath it was a passion for the music, and the hustle. I've had a soft spot for the gentle giant ever since.”

Fowley contributed to Steven Van Zandt’s Sirius XM Radio Underground Garage Channel in recent years. “Kim Fowley is a big loss to me,” Van Zandt told the LA Times. “A good friend. One of a kind. He’d been everywhere, done everything, knew everybody. He was working in the Underground Garage until last week. We should all have as full a life. I wanted DJs that could tell stories first person. He was the ultimate realisation of that concept. Rock Gypsy DNA. Reinventing himself whenever he felt restless. Which was always. One of the great characters of all time. Irreplaceable.”

–

All original photos taken by, and all ephemera courtesy of, Murray Cammick