AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

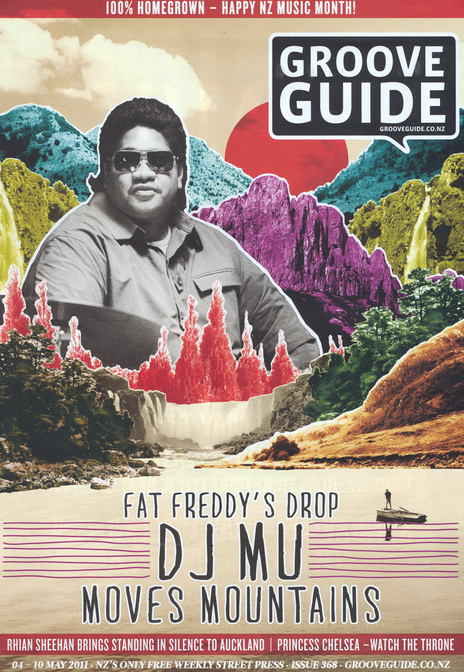

Mu

aka DJ Fitchie, Chris Faiumu, Christopher Ta’aloga Faiumu

A first-generation Samoan-New Zealander from working-class suburb Wainuiomata in Wellington’s Hutt Valley, he was the youngest of five kids. He spent his high-school days at Scots College, a fair distance from home.

“I was up in front of the headmaster on day one,” he told RNZ’s Yadana Saw in 2016, “I got into a fight and gave this guy a bit of a beatdown, so it was all up from there, really! It was all in my favour, I’d been called a name, a racist slur, and being from Wainui, the only thing to do was give him a beatdown. He never said it again. Off the back of that, I found my crew at the school and pretty much remained friends with these guys for the next 10 years.”

One of the few Samoans at the school, his surname was shortened to Mu, as the boys called each other by their surnames and they couldn’t cope with his.

Before going to university, Mu spent a year in the army. “I’d just spent six or seven years with some really good mates that were all going to Victoria University,” he told RNZ’s Sam Wicks in 2005, “and I thought a break would be good. I decided to go and do a year in the army, doing officers’ training, thinking that I would be getting paid really well and maybe get myself a free degree out of it.”

It didn’t work out. “I just don’t think I was quite suited to what they were after. I don’t regret going to the army, I had a ball while I was there. I got to blow up a tank, I got to work with the SAS in Auckland, abseil out of a helicopter, all that side of it. I pretty much got fired, didn’t make the cut. I came back to Wellington and decided to hook up with my mates again and go to Victoria University.”

Mu began studying towards a Bachelor of Science, but was drawn towards student radio.

Mu “flunked out” of university but on the plus side he discovered student radio

“I spent most of my time at university during the day playing basketball in the gym or hanging out,” he told Saw, “but once I discovered Radio Active, really that was all I did. I flunked out, eventually, but the plus side of that, I discovered student radio. [Radio Active] was very close to the graveyard, and that’s where you’d hang out if you felt you need to take a break from university life, and drift off and maybe have a little nap or sit on some poor old person’s grave and have a cigarette or something. You would be sitting there and you could hear the sounds drifting out of the on-air studio of Active next door.”

“I eventually got involved in doing radio shows,” he told Wicks, “and that was pretty much it for studying, really.

“It was pretty gung-ho in those days. I walked in, nervously walked up to the programme director [Helen Keivom] and said, ‘I’d love to get involved’, and she said to me, ‘What are you doing right now?’ She gave me a crash course in five minutes and I was on air straight away and did a terrible show. They didn’t seem to mind, and that’s where it all started.”

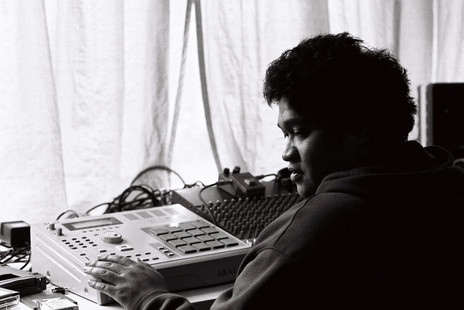

He studied audio engineering at Tai Poutini Polytech in Greymouth, then got a job as an audio engineer at Active. The radio station was where he first met Dallas Tamaira (aka Joe Dukie) and where he first came across the Akai MPC sampler, which would shape and define the sound of Fat Freddy’s Drop.

“I had a show on Active,” he told Saw, “I was doing the breakfast show for a little bit, and Dallas was an actor before he got properly into music, he was with Pacific Underground in Christchurch, and they were touring a play. I interviewed him for some promo for that particular show, and then we hung out for the weekend. It was obvious that he was more of a singer than he was an actor. We may have even made a beat that weekend.

“I was blown away by how well he could sing and straight away he started making plans to move to Wellington. He showed up with nowhere to live and no money, so we gave him somewhere to stay and the rest is history.”

Mu arrived on the Wellington music scene in 1991 as part of the legendary Roots Foundation DJ collective, which included Koa Williams (who also went to Scots College), Danny Lemon, Goosebump, and Marek.

“Fonky Monks might have just pipped the Roots Foundation,” Mu told Wicks. “Both of them were different styles, they were in similar times. I hooked up with Cian O’Donnell, Leon Surynt, Matt Morel, and that was very much a soul, funk, hip-hop based DJ collective, and I think that stemmed out of [Bar] Bodega when it first opened. You’d go there at nine o’clock on a Friday or a Saturday and watch a quite good independent band, it would be all over by midnight but Fraser at Bodega would have a licence until 3am. And then me and Cian would race in there with our turntables and quickly set it up. It was great, for a year there – you’d get two completely different crowds.”

One night at the Carpark in wellington, Roots foundation was born

Mu recalled to Saw the night that was the start of what became Roots Foundation: “People talk about moments in life when things connect, and it’s all a bit cheesy, but there was a night this did happen. Danny Scotford, Lemon, was running his own sound system night at the old Carpark [nightclub] in Willis Street, and Koa was possibly working at the Carpark, that’s why it was happening there. John Pell was there too. We all came together at this gig on the same night, and Danny had organised this ridiculously big PA from Western Audio, and stuck it in this room.”

The gig was also broadcast live on Radio Active. Mu recalled hearing the PA from two blocks away.

“I went along, had a listen, just couldn’t believe it – [I thought] this is the way it has to be, all the time. Many of us were disillusioned at the time, wanting to go and check things out downtown, and the music a lot of the DJs were playing was just horrendous, it was very commercial, and I think that, for me, that set me on this path to start organising parties and putting them on in interesting places with ridiculously big sound systems and delivering quite cutting edge and slightly rarer versions of reggae.

“Danny did a lot of his buying overseas, he would get it sent here from London. At that point there were some good record shops, but only a couple of them in Wellington. I took over working at Troubadour Records but even before that, I was buying records from people like Sir-Vere, he was working at Marbecks in Auckland.

“Being a DJ and being on turntables three nights a week around town, you’ve got time to kill, you pick up these things, and that eventually morphed into ‘I’m sure I could make this stuff’. I learned how to use a sampler in a basic way but that was enough of an insight into that world to go, ‘damn I need to [up my skills] ...’”

Mu purchased an Akai MPC 2000, which cost him around $2500 in the early 90s. “That was a lot back then,” he told Saw, “it all started picking up pace from there, pretty quickly. It didn’t take long before a lot of my tastes started getting a lot more electronic and a bit more out there.” He was learning how to manipulate samples and beats, and arrange all of this in a tiny little box.

Mu was living in Ghuznee Street, and “above us were our landlords who made a lot of noise, but we had super cheap rent, and we had a drum kit and the turntables and my huge record collection set up there, so it was just inevitable that I would start making some music out of there.”

He started using the MPC live straight away. “I was making beats that gave birth to Fat Freddy’s Drop, really. Kind of heading down that direction. Taking the sampler out into the club [along with a crate of records]. There was a period where that came along, and I probably don’t have enough perspective on it right now but I do think it was an important time, the 90s, really.”

Mu started Fat Freddy’s Drop in the late 1990s, with Dallas Tamaira and Toby Laing

Mu started Fat Freddy’s Drop in the late 1990s, initially with singer Dallas Tamaira and trumpeter Toby Laing as a loose jamming outfit which grew out of his DJ sets. They eventually picked up more members from other Wellington acts such as Ebb, Bongmaster and Trinity Roots. Laing was in about 18 bands around that time, including The Black Seeds, but shifted his main focus to Fat Freddy’s, as did a number of other band members.

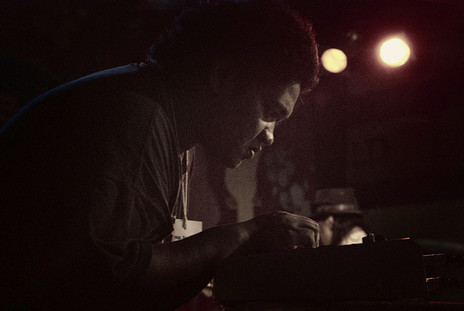

Live, Fat Freddy’s Drop didn’t use a drummer, relying instead on the rhythms and basslines crafted by Mu from his Akai MPC sampler. Mu was responsible for the band’s sound, mixing and dubbing them live from the stage. He engineered and produced their studio recordings in his well-equipped home studio – named The Beach, in Lyall Bay – for their first two albums, then from the early 2010s in their own warehouse rehearsal space, called Bays (after Bay Road, where it was located).

The band had been using this space for band rehearsals, but part of the space was a flat used by band member Joe Lindsay. They eventually persuaded him to move out so they could record there – Lindsay’s former bedroom became Mu’s studio control room.

Coincidentally the ground floor space below them was a tyre shop, but had once been home to Polygram Records’ vinyl pressing plant in the 1980s, and the upstairs space was used by Polygram for mastering.

Mu’s recording style with Fat Freddy’s evolved with the band. Initially making studio recordings that were coming out of live jams, they shifted with later albums to writing in the studio first.

“We’re born on the stage,” Mu said of Fat Freddy’s. “That’s kind of where we came from.”

“We’re born on the stage,” Mu told Red Bull Academy’s Tony Nwachukwu in 2005. “That’s kind of where we came from, and having to learn to write music and arrangements that were restricted to shorter lengths was quite a tough process for us as a band to learn how to do.

“When we were writing the [first] album, we went down many roads and had to retract and come back, and we’re just trying to find a process ... It’s mainly just trying to find a process that suited a band that was pretty much just a live improv band coming up with appropriate length arrangements for an album.

“How it worked in the studio with having to make tough decisions is, I was definitely steering the production and the studio and the engineering side of the album, but ... Because we’re a democratic band, it pretty much came down to whoever was prepared to stay in the studio the longest pretty much got their idea in there.

“The whole process for us is trying to include everybody in the band, everybody’s ideas, everybody’s melodies, everybody’s arrangements. It was kind of like one of those competitions where you’re at a radio station. You’ve got to keep your hand on the car, and you win the car, whoever keeps their hand on there the longest. Someone who’s there like four days later, that’s kind of how things happened. Just very natural, but if you’re stubborn and you stay in the studio and you’re there at five in the morning then you’ve got a better chance of your idea getting into the finals.”

The band and their manager, Mu’s partner Nicole Duckworth, took off for a UK/Europe tour for the first time in the middle of our winter in 2003. The band has continued touring there almost every year since, building up a solid fan base and playing to huge crowds at their own shows, and getting major billing at festivals.

Mu says they didn’t break even until their fourth time doing those jaunts. But by 2014 they were able to play a sell-out concert to 10,000 people at the Alexandra Palace venue (aka Ally Pally) in London. They managed to do that UK/Europe summer tour regularly with nine people in tow and still make money.

Mu and Nicole took their three-year-old daughter Mia with them on that first trip; family played a big part in the band. When discussing the four-year gap between their first and second albums, Mu mentioned a lot of the band members now had families, and they needed to work around everyone’s schedules. By his count there were eight kids in the Freddy’s whānau at that point.

“We don’t want to be pop stars,” said Mu

“We don’t want to be pop stars,” he told Nwachukwu. “There are different tiers of business in the music business and obviously the top level is where they’re making a lot of stupid money. But there’s a level where you can maintain some integrity and just make good music and still make nine-minute, 10-minute tracks and hopefully sell enough CDs to make a bit of a living. We just want to sit in there, maybe the higher end of that is the aim. We would be kidding ourselves if we expect to become pop stars. Maybe the lead singer might take off and do some R&B!”

The band always planned to be independent and carve their own path. They didn’t see any advantage to signing to a major record label when they had already built up a solid fanbase from extensive live playing and touring. A key part of that was releasing their music on vinyl: they knew that was the gateway to getting released overseas. Get DJs to play you and people will start to notice. Plus, the credibility of having your music on vinyl meant they were taken seriously. Almost all of their albums, whether studio or live, were released on vinyl. Not surprising, when one of the founders started as a DJ.

Their first vinyl release was a 12" of ‘Midnight Marauders’/’Seconds’, released in 2002 and billed as Fat Freddy’s Drop presents Joe Dukie and DJ Fitchie. Recloose, a DJ and musician friend of theirs in Wellington, was heading off overseas for some gigs and they gave him 10 copies of it to hand out.

A copy of ‘Midnight Marauders’ reached Daniel Best at German label Best Seven/Sonar Kollectiv, who released it in Europe the same year, with a dub version of the A-side added. They also connected with a UK label The Kartel, who released a 10" of ‘Hope’ in 2003.

“A few days after ‘Midnight Marauders’ came out here we went up to Auckland to play at Splore,” Mu told Sam Wicks. “I must have heard it at Splore five or six different times that day. Because it was on vinyl.”

‘Based On A True Story’ was the first independent album to debut at No.1 in the NZ charts

Their 2005 debut album Based On A True Story was the first independently released album to debut at No.1 in the New Zealand charts, and stayed there for 10 weeks. They released it on the band’s own label, The Drop (along with all their later releases), and distributed it via local company Rhythm Method. It sold 10,000 copies on the first day, which the music industry calls going gold. It quickly went double platinum, which is 60,000 copies, and kept on selling. The album cleaned up at the New Zealand Music Awards that year. After their awards were announced Mu seemed pleased to have won: “This helps Wellington’s bad NPC year – this will sort of smooth it over.”

“We’ve had a few people [from major labels] over the years, knocking on the door,” he told Yadana Saw, “but if you look at the people involved in Freddy’s, we are too smarty pants, too ‘We know what we’re doing’. If you sign to someone and hand all that stuff over you never know what’s happening. We were as interested in being business owners and running our own label, running our own business and knowing exactly what was happening to our money. We were just as interested in that as the music itself. It wasn’t even a decision, it just never made sense. We had great management – [Nicole Duckworth] knows what she’s doing. Our model of how we do things is very tailored to us. And that’s due to the fact we’ve kept it very in-house. Nicole knows in our band what each family and each band member requires to run their life.”

Outside the Freddy’s crew, Mu also produced releases by Rio Hemopo, Ladi6, Brother J, and Flowz, amongst others, and engineered Chris Tubbs’ 2003 album Good Days, Better Nights. Then there’s the countless remixes he did as well, for the likes of Salmonella Dub, Bigga Bush, Nightmares on Wax, Trinity Roots, Che Fu, Gin Wigmore and others.

In addition to the 2002 single ‘Midnight Marauders’, Mu and Dallas Tamaira recorded as Joe Dukie and DJ Fitchie on the 2004 track ‘This Room’ and the 2005 EP Seconds, although the line between the duo and Fat Freddy’s Drop is somewhat blurred.

In 2024 the band toured Europe twice, in summer and winter, and released their sixth studio album, Slo Mo in October. Mu described the album as “Afro rhythmic soul music, an exploration of Black music from Polynesia.” This succinct description also neatly captured what Fat Freddy’s Drop were all about, musically.

In 2025 the band shifted their base back into the centre of Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington. Mu was building a new studio and was enthusiastic about working on new music. He passed away unexpectedly in his sleep, in mid-July 2025.

--

With thanks to Yadana Saw and Sam Wicks

--

In July 2025 the Fat Freddy’s Drop whānau and the band’s many fans mourned the death of band founder Chris “Mu” Faiumu. AudioCulture will be publishing a tribute to Mu soon. Meanwhile, among the many reactions to his passing are tributes by Nick Bollinger and Martyn Pepperell:

For two and half decades, writes Nick Bollinger for RNZ, Mu was Fat Freddy’s “producer and their pulse. Though neither a singer nor a soloist, his presence was intrinsic to the band. That’s not just because of the imposing figure he cut on stage as he hunched over his MPC sampler, but also because Fat Freddy’s songs were built on the musical foundations he put down.”

Martyn Pepperell writes on his Substack page: “Mu was a beacon. He was like a lighthouse, and his legacy always will be. For a long time, he was Wellington’s lighthouse, shining his light on good tunes, good laughs, and good times. People knew him from record stores, bars, gigs, studio sessions, Radio Active, social sports games, or even just a wave and a nod on Cuba Street or out Lyall Bay way ... for a long time, Mu was like a lighthouse in Wellington. Then he became a lighthouse around New Zealand and further afield across Australia and Europe. I like to imagine they erect a statue of him in Berlin or Barcelona. We should get onto doing that here first.”

NZ On Screen profile for Joe Dukie and DJ Fitchie

Ep. 38 - DJ Fitchie AKA Mu from Fat Freddy's Drop ('The Bottom Of It' with Joshua Moriarty)

The Mixtape: DJ Mu (RNZ, 2016)

Mu - Fat Freddy’s interview. NZ Musician 2013

Gary Steel at Witchdoctor: DJ Mu tribute: The lost interview

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air