By 1972, Durney, his American wife and New Zealand-born twins were in Los Angeles, where his earlier trade of joinery helped make ends meet while he attempted unsuccessfully to get a foot in the door of the California club scene.

Born in Napier on 21 July 1942, Durney and his two brothers and two sisters grew up with a strict Catholic father and an opera-singing mother. “Mum was lovely,” Durney said. “She tried to teach me the piano, but I was only interested in playing outside. I wish I had taken it up.

“We used to be out in the sun quite a bit when we were kids, you know, at Ocean Beach, fishing and getting burnt and having big yellow blisters on our backs. We never had any protection back in those days.”

Frequent hospitalisations with recurring swollen glands in his neck meant Durney’s education at the Marist Brothers’ School in Napier and then as a boarder at St Patrick’s College, Silverstream, was anything but positive. He excelled at art and singing, becoming leading soprano in the choir, but none of his teachers picked up that he couldn’t read.

“I hated school,” he said. “I was taught by the nuns first, and then by the Brothers and priests at secondary school. They used to beat us. I was in and out of hospital and had to teach myself. I missed out on all the reading and arithmetic and couldn’t read when I left school. I just thought I was a dumb arse. But I sat myself down with the Bible and struggled through that and taught myself to read.”

When he left school, Durney took up a five-year joinery apprenticeship in Napier. “My father decided that that was what I needed to do, was to have a trade. That was unfortunate really because I didn’t like it very much. I finished it and became a joiner and did building and all that.”

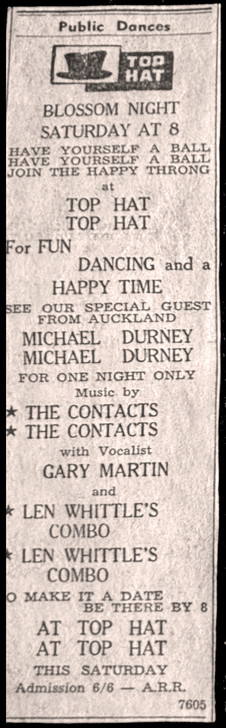

Throughout that period, Durney was singing the popular rock’n’roll of the day in the Hawke’s Bay clubs, talent quests and private functions with The Blue Caps and then solo. He was a regular feature for Bernie Meredith at his Top Hat ballroom, where he was often backed by The Ernie Rouse Trad Band.

With his guitar between his legs, Durney rode from Napier to Auckland on his Vespa

With his apprenticeship done, Durney decided to try his luck as a singer in the big smoke. “So, I put my air force jacket on, my guitar between my legs, and took off up to Auckland on my little Vespa scooter,” he told AudioCulture. To the Sunday News in 1969 he described the journey: “I travelled through Gisborne and Tauranga, and it took me three days to reach Auckland. I had no idea what awaited me when I arrived.”

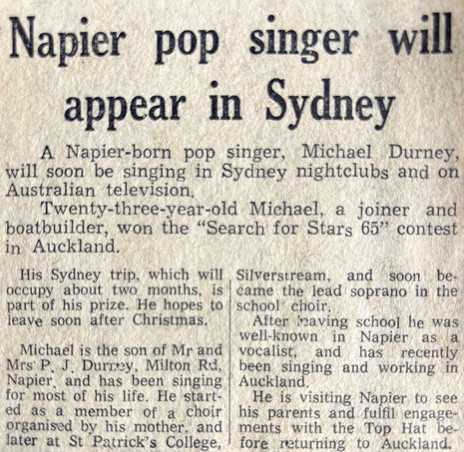

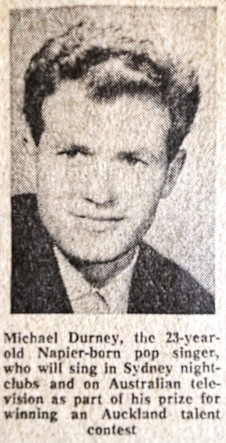

Arriving in the city in 1965, he took jobs in factories while he looked for opportunities. “When I first came up to Auckland on my scooter, I used to go round clubs and sing for nothing, just to sing. So that’s how I kind of got my experience with clubs and so on.” Later that year, he won the Shiralee nightclub talent quest.

One of his first paying gigs was for Nick Villard at the Embers club. In fact, the club became a regular post-gig hangout. “After shows we would go to the Embers to have little singalongs,” Durney said. “We’d take our guitars, and we had a great time in the Embers.”

A significant break came when Mike Durney spied a newspaper ad from a publishing company looking for a “castaway” on Great Barrier Island to publicise the 1966 Tom Neale autobiography An Island To Oneself. At that time, Neale had lived alone on the island of Anchorage in the Suwarrow atoll of the Cook Islands for a total of six years over two stints.

Although Durney wasn’t selected, he read Neale’s book and wrote a song of the same name. When he sang ‘An Island To Oneself’ for the publishing company, they loved it and had him perform it on TV. Watching at home was a bigtime Auckland promoter.

“That’s when Benny Levin saw the television show,” Durney said. “He called me up and said, ‘Would you like to have a meeting with me, and would you like to sign up and I’ll take you on?’ So, I said, ‘Yeah, okay.’ Because Benny was called the Gentleman Promoter then. But he took me on, and we signed up for three years, and he gave me a lot of work.”

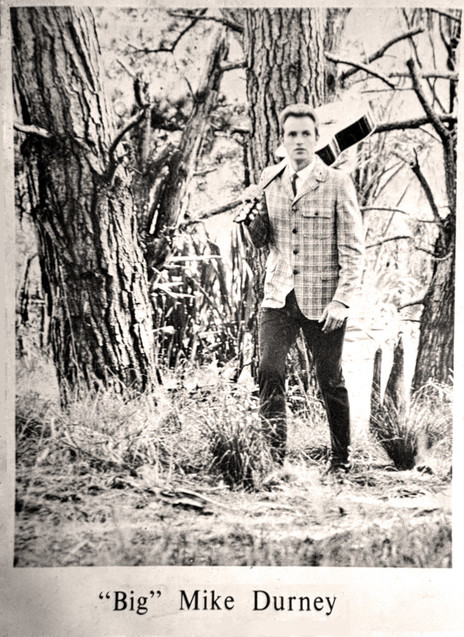

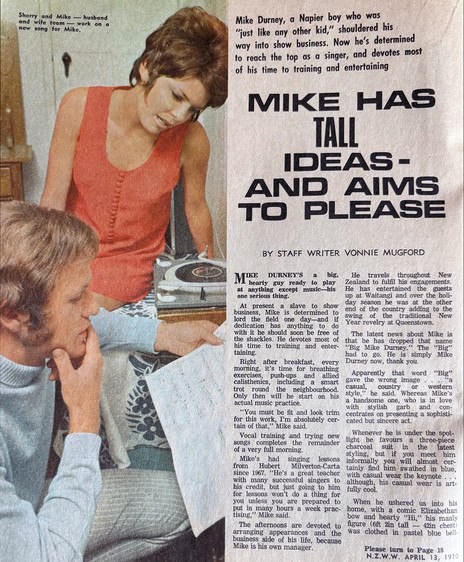

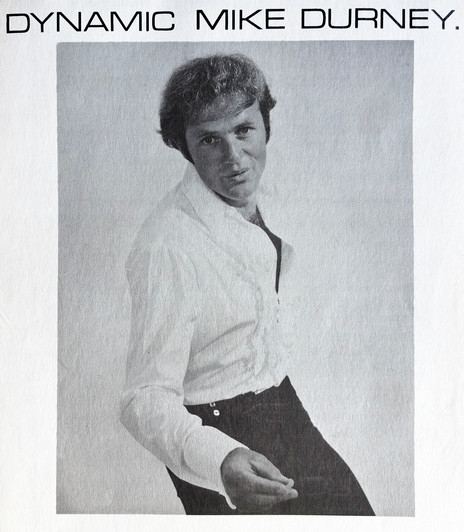

The first thing Levin did upon observing the singer’s athletic 6'2" (1.88 metres) frame was give him the stage name Big Mike Durney. “Benny said, ‘We’ll put Big there,’ and I said, ‘Oh, well, do you think so?’ I was just a kid, you know? I thought it was a good idea and so we went with that.”

Benny Levin steered Durney away from pop ballads towards country-and-western music

Then Levin steered Durney away from the pop ballads, by the likes of Tom Jones, that he had been performing towards country-and-western music. Three of the 10 finalists in the 1966 Loxene Golden Disc were country records; the artists were John Hore, Ken Lemon and Maria Dallas, who won with ‘Tumblin’ Down’, and perhaps Levin felt he needed the genre represented on his new record label Impact.

“I used to sing ballady-type songs because that was what my voice was like,” Durney said. “Benny felt that country was the thing to go for, and so I went into it, really. But it was mainly ballad songs and that type of thing we used to sing at clubs.”

Durney’s debut single was released on Impact in December 1966 in time for his inclusion on the Impact Show tour of beach resorts over the Christmas-New Year holiday. The flip side was Durney’s ‘An Island To Oneself’, but for side one Levin chose ‘Many Yesterdays Ago’ by Auckland songwriter Jim Ruane. Ex-Royal Navy, Ruane had emigrated from England to New Zealand in the mid-1950s and already had cuts on John Hore and Ken Lemon records.

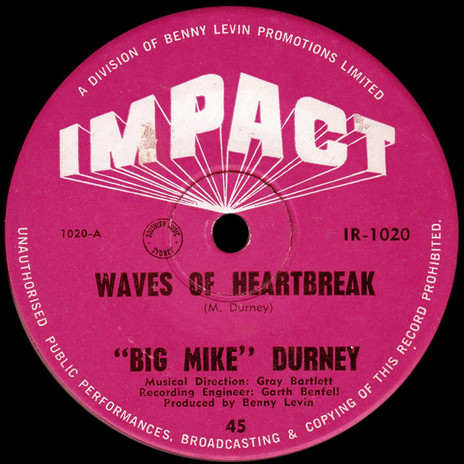

In the new year, the sides were reversed on Durney’s follow-up single: his own ‘Waves Of Heartbreak’ took the A position while Ruane’s ‘My Heart’s Like A Merry-Go-Round’ was on the B-side. Also, Durney made the first of many television appearances, singing Roger Miller’s ‘King Of The Road’ on C’mon.

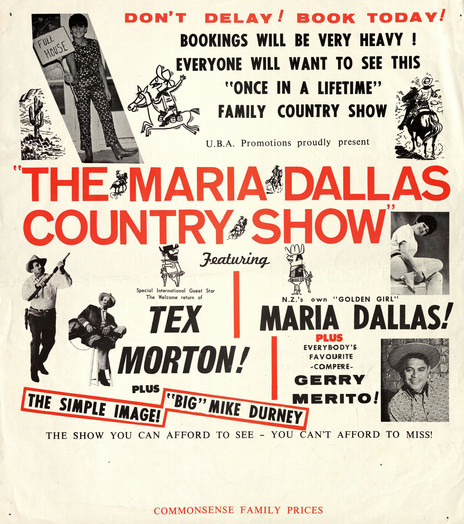

He toured movie theatres in July 1967 as an opening act to the Nashville film Country Music On Broadway (released in the US three years earlier). Then he set out for five weeks on the Tom McDonald-promoted Maria Dallas Country Show. The package also included Tex Morton, Gerry Merito and The Simple Image.

It was time to record a Big Mike Durney LP. Produced by Benny Levin at Mascot Recording Studios, with musical direction by Gray Bartlett, Country Style included the four sides already released, as well as souped-up versions of the Everly Brothers’ ‘Bye Bye Love’ and the Māori Cowboy Johnny Cooper’s ‘Lonely Blues’ (aka ‘Look What You’ve Done’), already a Kiwi party favourite.

Surprisingly, Durney yodelled on his versions of ‘Bye Bye Love’ and ‘Lonely Blues’

Surprisingly, both cover songs included a bit of a yodel, although not to the extent of a Les Wilson or a Max McCauley. The adoption of the technique was at odds with what Durney had told the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly in April 1967 while discussing his transition to country music: “The simplicity of the songs appeals to me. I prefer slow ballads in the Jim Reeves and Roger Miller style … and I don’t like yodelling.”

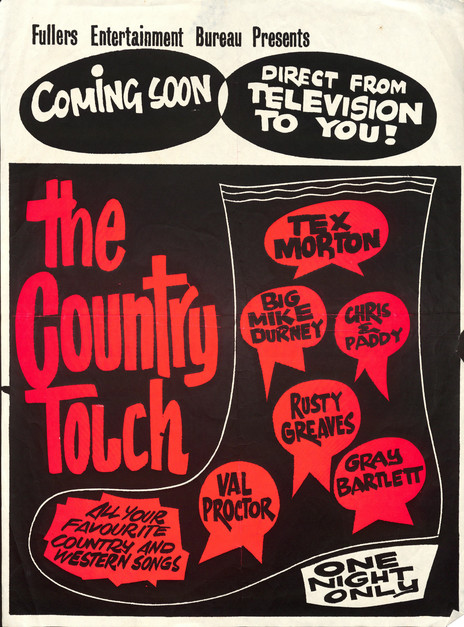

In 1968, Durney appeared on the new NZBC TV show The Country Touch and toured with the programme’s stage show alongside duo Chris and Paddy, Val Proctor, Gray Bartlett, Rusty Greaves, and host Tex Morton, who performed his sharp-shooting act as well as singing and hosting proceedings.

That was followed by the Blast Off 68 Pop Spectacular with Australian pop star Johnny Farnham, Larry’s Rebels, The Hi-Revving Tongues, Gene Pierson and Ray Woolf. At the end of the year, he was a guest on TV’s The Late Show, donning a bow tie and tuxedo to sing jazz arrangements of ‘Night And Day’ and ‘Up A Lazy River’.

Although the Auckland Star reported at the time that the move away from country was permanent, there was at least one more appearance on The Country Touch before Big Mike Durney’s exclusive three-year management and recording arrangement with Benny Levin ended in the middle of 1969.

“After three years, Benny asked me to join up with him again and I didn’t,” Durney said. “I decided not to, and I went on my own, which was a silly thing to do, really. I should have joined with him again, because he had all the contacts and everything. But I went on my own.”

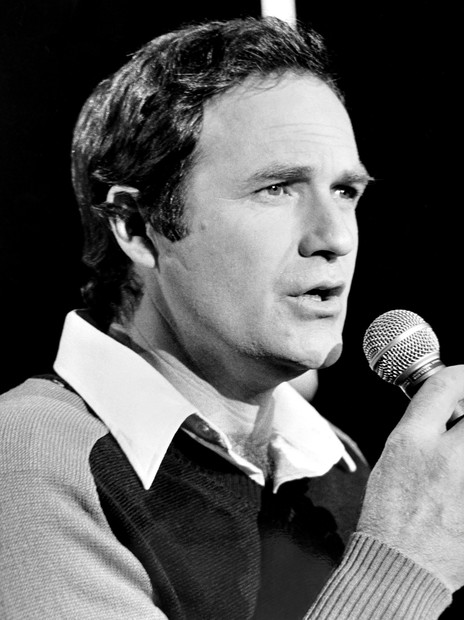

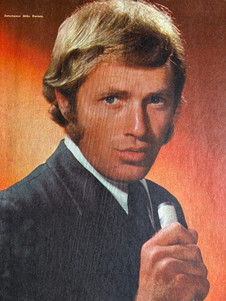

The first thing he did was retire the “Big” descriptor, telling the NZ Woman’s Weekly in April 1970 that it gave too much of “a casual country or western style” impression. He was a guest on the Eliza Keil-hosted episode of the series A Girl To Watch Music By.

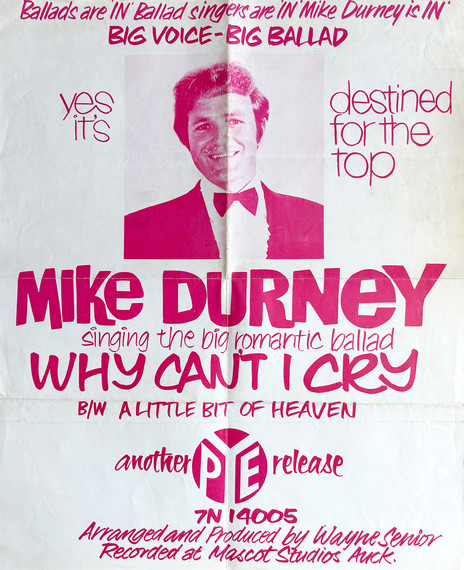

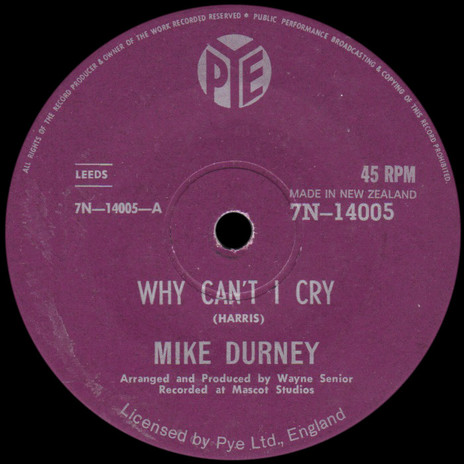

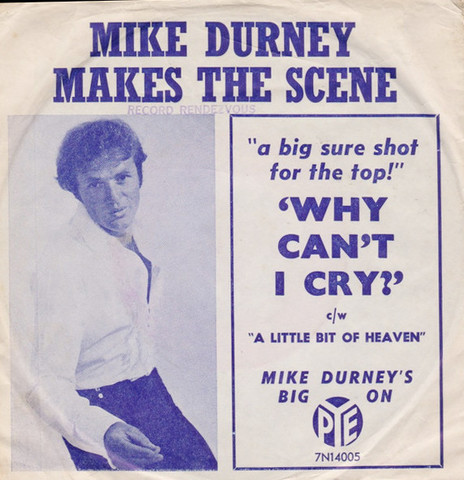

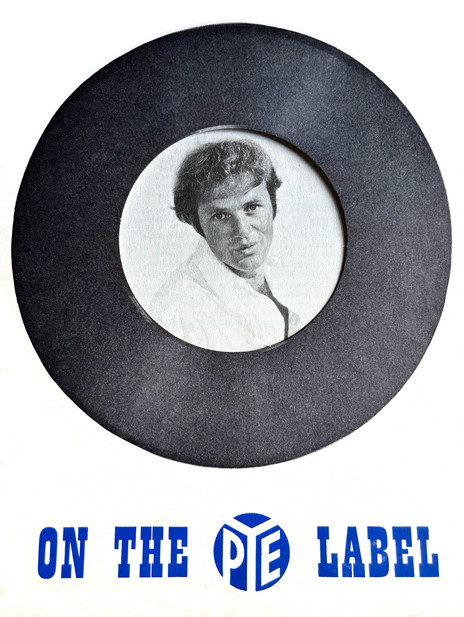

Durney’s initial recorded foray away from country music was ‘Why Can’t I Cry’ b/w ‘A Little Bit of Heaven’ for Pye, arranged and produced by Wayne Senior at Mascot in June 1969. The previous year, Senior had had a production hand in Allison Durbin’s Loxene Golden Disc winner ‘I Have Loved Me A Man’.

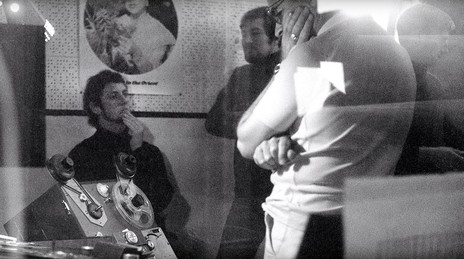

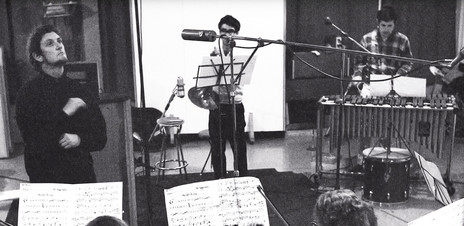

Senior, who passed away on 9 January 2025, posted a video on his YouTube channel in 2021 that highlighted a collection of photographs by the session’s drummer Bruce King. Senior wrote: “Musicians on the recording include guitarist Gray Bartlett, bass player Billy Kristian (Billy Karaitiana), drums Bruce King, John Pickworth vibes, Graeme Stentiford on [flugel] horn, Neil McGough, Pete O’Gara and Brian Biddick trombones. I don't recall many of the names of the string section or the flute player.”

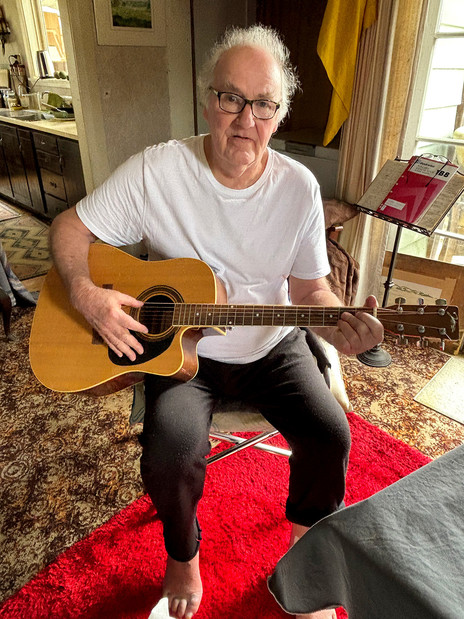

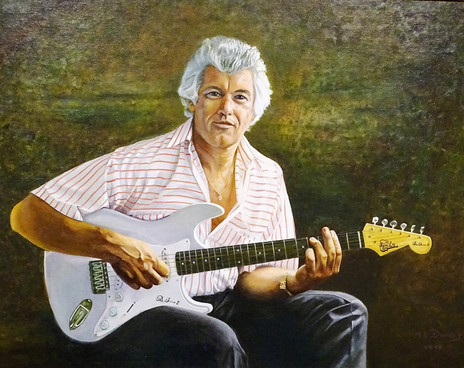

Retired in Northland, Durney has the occasional jam at the Dargaville music shop

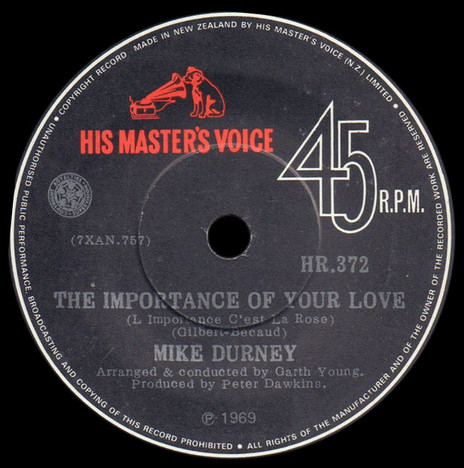

No sooner had ‘Why Can’t I Cry’ been released and Mike Durney was lured away to HMV. His first single for them was ‘The Importance Of Your Love’ b/w ‘Our Song’, which was arranged and conducted by Garth Young, and produced by Peter Dawkins. Durney’s Pye single, ‘Why Can’t I Cry’, made the final 10 in the Loxene Golden Disc, but ‘The Importance Of Your Love’ missed out. Wayne Senior, who also produced finalist ‘The Hunt’ by Larry Morris, was awarded the inaugural producer’s award.

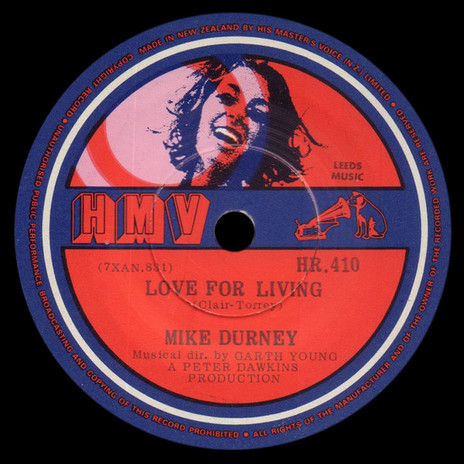

Two more Dawkins-produced HMV singles – ‘It’s Not Easy’ b/w ‘Love In Every Room’ in 1969, and ‘Love For Living’ b/w ‘Take Your Time’ in 1970 – may have continued to show off Durney’s vocal chops, but they failed to excite the record-buying public. In February 1971, he told the NZ Herald: “I am now waiting for the right material to record, but good material is not easy to find.”

During the following year, he moved to the United States with his Californian wife Sherry and their toddler twins. Based in Southern California, he tried to get some club gigs, but things didn’t work out. “We went over to the States for four-and-a-half years, and that was an unfortunate thing because I left show business at that point,” he said. “I had to get back into joinery to make a living.”

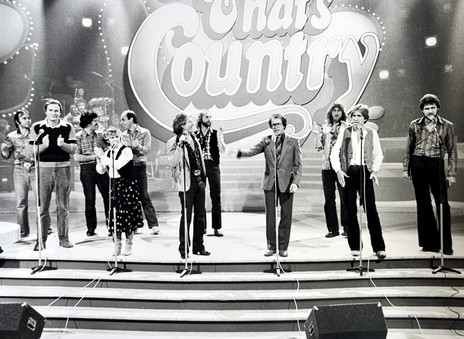

By the end of the 1970s, they were back in New Zealand, but the scene had changed so much and Durney had lost all his contacts. There were appearances on That’s Country and Hudson & Halls in the early 1980s, but Durney concentrated his efforts on his own furniture business in Auckland.

Based in Muriwai later in the decade, he turned his hand to painting professionally. It had always been a hobby since his youth. Former prime minister Sir Robert Muldoon, Bishop John Mackey, businessman Bob Owens, and Durney’s one-time musical director Gray Bartlett all sat for portraits.

These days, Mike Durney is retired in the Kaipara District of Northland. Now and then he attends a local country music club for a sing or rocks up to the music shop in Dargaville where he and the owner grab guitars from the display and jam. At home he’s teaching himself to play the piano, as his mother had tried to do all those years ago in Napier.