This excerpt from Christine Mintrom’s book NZ Musicians in Australia, volume two describes the scene in Sydney that New Zealand musicians found when they arrived in the mid-1960s, usually by boat.

Sydney Harbour, photographed from the deck of the SS Canberra by Auckland drummer Bruce King, c. 1966. "We came over here on a ship," recalled King, " 'cause we could bring our drums, all our guitars, keyboards. Much cheaper. You couldn't take much gear on a plane."

From the very late 1950s to the mid-1970s, the contrast between Sydney and Melbourne and New Zealand cities was quite pronounced. For most Kiwi musicians, going to Australia meant going to Sydney. A few bands did go to Melbourne, some briefly before then heading to Sydney. Of the bands who purposefully came to Melbourne, like The Chants R&B, they did so because they had sent an advance scout who established that they would fit into the Melbourne music scene best.

For decades Sydney was known for offering numerous events and had a reputation for lively, often racy entertainment. Following World War II, 400 new club licenses were issued, allowing clubs to become prominent in New South Wales. Sporting clubs, ethnic clubs and leagues clubs took up the opportunity to obtain licenses.

By the 1960s, NSW clubs offered various forms of amusement, including live music and poker machines, and affordable meals plus affordable alcohol, and with this combination they became magnets for locals, people from other parts of Australia, and visitors from overseas.

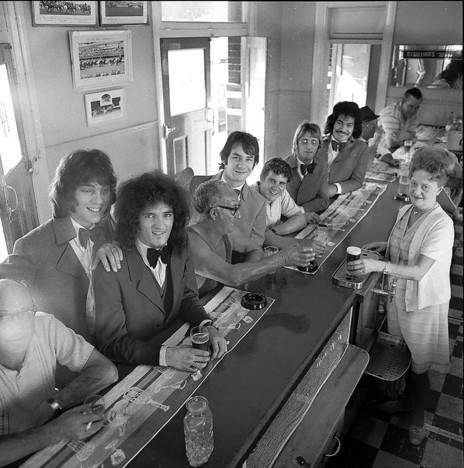

Max Merritt with, to his left, Bobi Petch. Rex Hotel, Kings Cross, 1965 - Bobi Petch collection

For musicians, breaking into some of the established venues wasn’t always easy. Max Merritt spoke about the early trips he and the Meteors made to Sydney, circa 1963-1964.

“It was a helluva business to get into Australia in those days. They were quite content with all the variety acts around the clubs. You were dealing with all the old school of guys. Graham Dent [former Auckland promoter] was instrumental in breaking into that. We played some outlandish gigs. We played down at the Silver Spade, played a gambling joint on Castlereagh Street ... We should never have played there. It had poker machines, people were telling us to ‘turn it down’ ’cause we were drowning out the poker machines. But it was in the days when rock and roll was sorta in the formative years as far as entertainment went.”

The Simple Image had a brief look at Sydney when they were on a cruise ship as the ship’s band. This was when the Castaways were working in Sydney. Cass Gascoigne, bass guitarist for The Simple Image, picked up the thread.

Simple Image, the Sydney line-up (L-R): Bruce Walker, Barry Leef, Wayne Allen, Cass Gascoigne, Harry Leki. - Cass Gascoigne Collection

“We sought out the Castaways, who had Frankie Stevens out front. They showed us around the Sydney night scene.”

Barry Leef (Simple Image’s rhythm guitarist and primary vocalist): “We were thinking we might go to England, but when we saw Sydney we just thought, ‘We’d be crazy to go to England ... We could earn $120 per week. This is the place you’d want to be.’”

Of his early time in Sydney (circa 1966), Mike Perjanik recalled, “The leagues clubs just blew us away. Like Las Vegas. We went out to the St Georges Leagues Club. I think the house band there was a 16-piece big band.”

He spoke of the contrast between New Zealand and Australia. “There was quite a difference between the two places. Now not. But then there was a giant difference from an entertainment-music industry perspective.”

Dave Miller arrived in Sydney in April 1966: “In its own way, it was a mini Las Vegas. Palatial places like league clubs, RSL clubs and motor clubs hours were extended beyond pub hours, and thanks to pokies, good fees operated seven nights a week with great floor shows. Liquor licensing could really be made by quality acts. If you went into that circuit armed with two or three previous hit records, then if you played your cards properly you had a home for life and a good income”

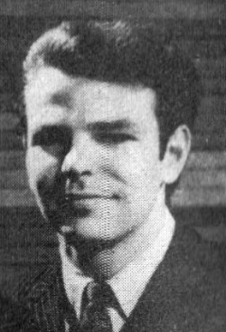

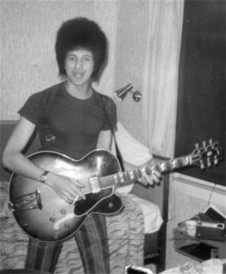

Bruce King, drummer with Mike Perjanik's band when it went to Sydney; photo from 1967

Some New Zealand musicians who came travelled by sea, as Dinah Lee did late in 1965. A year later Mike Perjanik and the band also came by ship. Bruce King (drummer with the Perjanik band) said, “The band sailed into Sydney Harbour on the Canberra past a half-completed Opera House. This was impressive, as were the much taller buildings in the CBD ... We came over here on a ship called the Canberra ’cause we could bring our drums, all our guitars, keyboards. Much cheaper. You couldn’t take much gear on a plane.”

Travelling by sea didn’t appeal to everyone, though. Dinah Lee: “I left with Jim Haddleton to come here. By ship, would you believe? By ship in 1965! Gggrrrr.” She’s right. By the mid-60s, people coming to Australia more often arrived by air rather than by sea. For those arriving on a plane that flew low as it descended and used a flight path that included the harbour, city and the inner suburbs, great glimpses would excite them. There were miles and miles of houses with red roofs interspersed with the green treetops. Arriving at night was magical. Brian Peacock said, “The Librettos flew across the ditch into Sydney in 1965 on a night flight and we were overwhelmed looking down from the plane at the Big City lights as it was the first trip overseas for all of us.”

To pause briefly to consider Sydney more broadly ... It was and still is visually pleasing. Photogenic. The harbour greeted arriving immigrants by showing off its little bays. Ferries and ships plied the water, and yachts dotted the bays, while the northern and southern sides of the city were linked by the elegant Harbour Bridge. Though it’s hard to comprehend now, most New Zealand musicians covered in my book arrived in Australia before the Opera House was completed – it didn’t open until 1973.

During the 1950s and 1960s Sydney experienced a “long boom”, with most people employed, with disposable incomes and cars. In that decade, mostly thanks to a mining boom, Sydney became a financial hub, and many companies located their head offices there. Luxury hotels were built in the 60s and the start of the 70s, with the largest number of hotels in the King Cross-Potts Point vicinity, an area favoured by tourists.

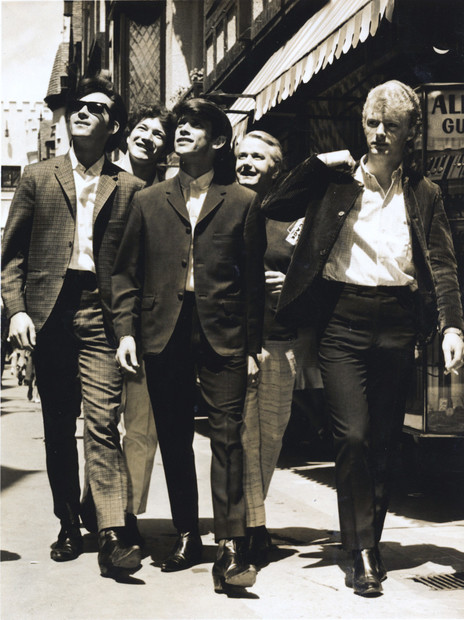

September 1964: Ray Columbus & The Invaders check out Australia - Perth, to be specific. From left: Wally Scott, Billy Kristian, Ray Columbus, Jimmy Hill, Dave Russell. - Simon Grigg collection

The 1960s was when a huge number of Kiwi musicians began arriving. Many started their time in Sydney living in the Cross. In that decade the area had affordable accommodation in older, cheap hotels such as the Plaza, the Paris, the Americana, and the Grey Eagles Hotel. The notorious Plaza Hotel was just 100m from the Pink Pussycat with its hourly racy girlie shows. Barry Leef lived at the Plaza, as did other musicians like those in The La De Da’s. At first, Mike Perjanik lived at the Americana at the top of William Street. He remembered, “I needed to get out of there. We moved out after two-three weeks. I lived just out of the Cross in Elizabeth Bay in a little apartment.”

In Sydney, Kiwis who’d moved there tended to keep in touch with other Kiwis. Those in work and with agents introduced new arrivals to these agents. Dave Miller had come over with another Christchurch musician, Dave Henderson, and recalled, “We ended up sharing digs in the Kings Cross red-light district. Unbeknown to us of course ... The girls [that is, the working girls] were soon teasing us about being their pop stars because they could hear us rehearsing. We were living directly over the road from Max Merritt and the Meteors. Like a New Orleans ghetto, we used to hang out of our respective windows and laugh and joke with each other across the road.”

Many of the Kiwi musicians who came to Sydney were still teenagers. Some recalled how sheltered their lives had been back in New Zealand, like Lindsay Field who came from Wellington to join the cast of Hair in 1969: “I was quite naïve.” He was acutely aware of the contrasts he first saw in Sydney: “It was full of Americans on R’n’R – full of hookers and shady shysters.”

Kings Cross had been an entertainment hub for the city for years. It had a colourful history, and from the early 1900s was the bohemian area of the city, attracting artists, writers and musicians. From World War II onwards the Cross housed brothels, strip clubs and night clubs, and with those came drugs, prostitutes, criminals and a lot of booze.

Looking east along William Street towards the corner of Victoria Street and Darlinghurst Road, Kings Cross, Sydney, 1962 - Len Stone / City of Sydney Archives

For young Kiwi band members there in the 60s, the Cross was alive with sensations: bright lights, blaring car horns, wailing sirens, loud voices, drunken voices. There were flashing ads, punch-ups, and laughter for hours of every twenty-four. And the occasional shooting. The area was edgy, exciting and overwhelming. Brian Peacock commented that Sydney was a “real eye-opener for us and seemed very fast after the more sedate New Zealand cities.”

Barry Leef lived in the Cross for two years from 1969: “I was very comfortable. It didn’t feel dangerous walking down a dark alley on a dark night in the Cross. It was fine. It felt safe. The Cross became a drug den and got pretty bad, but when I first came it wasn’t like that. There were people out in the street — hookers on every corner. Just fun, really good fun!”

During 1969 many of the cast of Hair! integrated into the Cross. Lindsay Field recalled, “As we became part of the society here you realised there was quite a strong community that serviced Kings Cross. In every way.” He giggled. “If you were part of that community there was a whole different relationship. We would sit and have a drink with the hookers at the Venus Room down the road from the theatre after the show. And they were your friends.”

The La De Da's taken in a King's Cross laundromat shortly after they arrived in Sydney, 1967.

The La De Da’s had rubbed shoulders with creatures of the night in Auckland when they played late upstairs at the Platterack, but after each gig they went home. Even earlier, Larry’s Rebels (with high-school boy John Williams) played upstairs at the Platterack. Now The La De Da’s were living alongside some of the Cross’s colourful characters.

Very near the Cross, Potts Point also provided accommodation where Kiwi musicians lived, like Dinah Lee: “When I first came here I flatted in Potts Point.” After Bobi Petch became her PA, they shared Dinah’s flat. Dinah spoke more about this building: “Billy Thorpe was on one floor. Jackie Holme on another floor.” (Jackie, Max Merritt’s girlfriend at the time, had run the Casual Shop in Auckland and was the one who gave Dinah her distinctive haircut and made many of her clothes.) Max was in the building. Tommy Adderley and his wife Colleen were there when Tommy was singing with the Mike Perjanik Band. And out-of-town musicians like Lynne Randall stayed with Dinah and Bobi when they were in Sydney.

Dinah spoke about socialising with other musicians when she was first in Sydney in the mid-60s: “We all would meet in Kings Cross. In those days would walk. There were little coffee shops... After your gig you’d say, ‘We’re meeting in Kings Cross.’ All of us from Ray Brown’s band, Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, all the groups that came up from Melbourne, we’d have coffee or a party.”

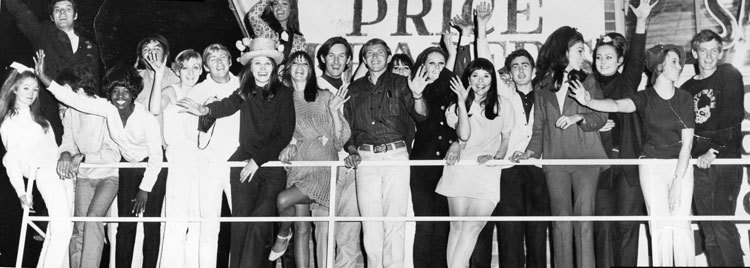

The 1967 Sydney birthday party for Dinah Lee, with Little Millie Small (4th from left), Dinah (in straw hat), Ian Saxon (white trousers), Allison Durbin (next), Bobi Petch (2nd to right) - Bobi Petch collection

Australian popular culture history James Cockington observed that from 1945 to 1955 when immigration from the UK and Europe was at its peak, Sydney was drawn to lots of aspects of American culture. Jim Keays (of Australian band the Masters Apprentices) commented that clubs in Sydney were run the American way, which contrasted with other parts of the country. The Vietnam War raged for most of the years covered by this book (with US troops involved from 1962), and from 1967-1971 American servicemen used Sydney as a rest and recreation destination.

Some members of Kiwi bands were aware of the Americanism; some deemed it to be brash when compared to New Zealand cities. In 1966, when the Mike Perjanik Band with vocalists Tommy Adderley and Allison Durbin came over, Mike loved Sydney’s vibrancy and found the city welcoming. But that Christmas, Tommy saw a sign in the Grace Brothers’ store that read, “Three Santas. No Waiting.” He was unimpressed.

Mike Perjanik band, Sydney. Mike is on keyboards, to the left; vocalists Allison Durbin and Tommy Adderley are centre back, and Bruce King is on drums. - Bruce King Collection

Barry Leef commented, “Sydney had an intensity about it ’cause the Americans came with lots of different attitudes: some frightened, some scared, some in a bad way, some really over the top. A lot of money was being spent. There was the attitude that this two weeks could be it. It was a life; be in it or be out of it. So it was full-on.”

There was LSD around Sydney, brought in by the GIs on leave from the war. It wasn’t illegal in the mid-sixties in NSW, but the law changed by 1967 and it became illegal. The GIs brought other illicits in too, like heroin, and helped to create a market for drugs. Marijuana began to be grown and cultivated alongside fruit and vegetable crops in the Griffith region and was trucked to Sydney with the fresh produce.

Owners and managers of some of the clubs and music venues were known to have had underworld links, and coppers were encouraged to turn a blind eye to some of the gambling, prostitution and various petty issues, aiming to keep US servicemen happy while they were in the NSW capital.

Christchurch musicians, including Max Merritt, Ray Columbus, and Dave Miller, had often performed for servicemen before leaving that city. In Sydney, Kiwis provided a lot of music that appealed to the GIs on leave, and there was money to be made by allowing those men to enjoy the music they liked. But the effect by the early 70s was, as music writer Ed Nimmervol noted, that the music scene in Sydney had the air sucked out of it. He believed that this made it hard for contemporary rock bands to get work, whereas in Melbourne, the music scene was vibrant.

Yet there was still a lot of work in Sydney for musicians, in nightclubs, at teenage dance venues, leagues clubs, pubs ... In the latter years of the 60s, many Kiwi bands played in nightclubs such as the Whisky A Go Go, the Silver Spade Room (at the Chevron), Latin Quarter and the Rex Hotel. The Chevron opened in 1960; the Silver Spade Room was a lavish 600-seat theatre restaurant on the first floor where shows were held every night. (It was demolished in 1985.)

Kings Cross had large, grand theatres, among them the Kings Cross Theatre on Darlinghurst Road which seated 5000. Surf City was also located there – it could hold and at times did have 5000 people in during a day. It was where Ray Columbus and the Invaders had played early in their time in Sydney. There was Jungle (where The La De Da’s played on their first trip to Australia), run by 2UE jock Ward Austin, and for teenagers in the mid-60s there were sound lounges like the Bowl and the Op Pop. No alcohol was served at these lounges. They were small (run on an American model) with small sound systems. They were open at lunchtime to attract young city workers to listen to music; many did spend their lunchtimes there, and these venues allowed bands to play during the day.

Christchurch's The Dave Miller Set, whose ‘Mr Guy Fawkes’ was an Australian smash hit in 1969.

Not long after Dave Miller arrived in Sydney in 1966, he went into the Bowl one day and spoke to Graham Dent who was then managing that venue. Graham offered Dave a job that involved introducing acts and playing records, starting at 7pm that night. Quickly those two tasks grew into more, with Dave’s role extending to organising shows and being resident vocalist. Dave remembered: “The Bowl operated seven days a week – lunchtimes from midday to 2pm and nights from 8pm till midnight. Monday and Tuesday nights were closed because they were traditionally very slow. Saturday and Sunday afternoons were also big due to younger audiences.” He worked at the Bowl for six months until he formed the band which became the Dave Miller Set.

For years the Mike Perjanik Band played at leagues clubs – the Parramatta Leagues Club first, then the leagues club at Balmain for a long stint. There was work for bands at well-known pubs in the suburbs, such as the Oceanic in Coogee and the Manly Pacific, and throughout the Sydney suburbs local pubs hosted bands and in local halls there were dances. By contrast, large outdoor shows were held at the Sydney Stadium in Rushcutters Bay.

The Oceanic Hotel, Sydney, where lots of New Zealand musicians worked in the 1960s. - Bruce King

I asked Mick Leyton for his impressions of Sydney, compared to Auckland, at the time he arrived in 1967. “It was much busier and noisier,” he said. “I couldn’t get over the clubs and the big places to play, like the Latin Quarter and Whisky A Go Go. It was all very sophisticated. The main thing I remember was that older people went to music clubs. In Auckland it was very teenage-ry still. You very rarely saw anyone in the crowd who was over 22 or 23 years old.” He recalled “the general excitement and older people who were doing things that in New Zealand younger people did. ’Cause in New Zealand, once you got to 22 or 23 you didn’t go out; you went to work, and you had a family. I don’t know what it’s like now ...”

Radio in Sydney was leaps and bounds ahead of New Zealand. The city had independent radio stations from the 1920s. 2UE and 2UW had begun broadcasting by 1925, and the latter had 24-hour broadcasting by 1935. As early as 1958, an American-style Top 40 began on 2UE. Listening to the drive-time shows on that station or 2SM in the mid-60s was exciting. The programme was bright, upbeat and alive, with an output nothing like that broadcast by the dreary commercial stations across the Tasman.

In NSW, closing time for pubs was 10pm and had been since 1955, whereas 10pm closing was not introduced in New Zealand until 1967. Writer Beverley Kingston noted that entertainment in the leagues clubs had “helped foster variety-style entertainment that flowed into Sydney television.”

On Australian TV, Bandstand copied the American programme of the same name and was hosted by New Zealand broadcaster Brian Henderson. Beginning in 1958, it was broadcast from Sydney by Channel 9. As it was deemed to be a family show, it was conservative and middle-of-the-road, but it did provide opportunities for musicians to be exposed to a wide audience. Many New Zealanders appeared on this show over its 14-year reign, including Johnny Devlin, Bill and Boyd, Lyn Barnett, Dinah Lee, Allison Durbin, Sandy Edmonds, and Ian Saxon. In the clip above, Max Merritt and the Meteors appear in a Bandstand live concert in 1965.

Bandstand was not the only TV music show aired in those years – there were others including Saturday Date and the ABC’s Six O’clock Rock (later renamed Sing, Sing, Sing) which began in February 1959 and went to air at 6pm Saturdays. It was recorded in front of an audience, and people booked seats weeks ahead to ensure a spot.

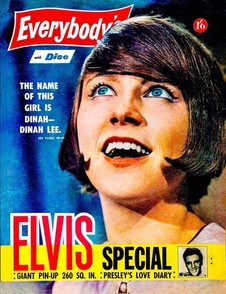

Everybody’s magazine began in Sydney in 1961. Early on it was a women’s magazine, but in the years 1963-1964 it changed its focus to pop music, movies and television. It was influential, selling well in Australia, and as it was also on sale in New Zealand it gave Kiwis some idea about what was happening across the Tasman.

Dinah Lee on the cover of Australian magazine Everybody's, c. 1965. When this image was posted online in 2020, she responded, "But unfortunately I am not in Presley's Love Diary ..."

Sydney had (and still has) a beach culture and going to the beach was a pleasure sought by many. Lots of New Zealanders lived near the beach in Bondi. For a short time from January 1963, around the time the Denvermen recorded their No.1 hit single ‘Surfside’ (written and produced by Johnny Devlin), Sydney took to surfing in a big way. This was at the time there was a parallel craze for all things surfing on the West Coast of the States. Australian surfing music blossomed.

The surfing phenomenon had its own dance, the Stomp, which became a craze in its own right. But when the Beach Boys did shows in Australia in January 1964, the days of surfing music were almost over. The Beatles tour of Australia and New Zealand in June 1964 spelled the end to much of the interest in surfing music and the Stomp. By 1966 Surf City had closed, and there was distinct movement south to Melbourne for many bands.

The Plaza Hotel in Sydney’s King Cross was mentioned by lots of people I interviewed, so it is important that there is more information about it at this point.

This hotel is still operating in the Cross, these days for backpackers, but during the 60s it was one of the hotels in Sydney’s Kings Cross that offered musicians affordable accommodation. There were other older, cheap hotels too, like the Americana, but years on it’s the Plaza that people still talk about. Mick Leyton, who moved to Sydney in 1967, noted, “It was as big a rock icon as any other thing in town.”

The hotel was a near neighbour to the Pink Pussycat on Darlinghurst Road. Mick remembered, “It was two storeys. There was a lounge downstairs full of girls. They were just available. On the first floor was all pop acts.”

New Zealand had nothing quite like the Plaza, and so many New Zealand musicians stayed there. Mick said, “I lived there; Yuk [Harrison] lived there; Thorpie and the boys lived there when they came to town; Max and the boys; Evan Silva and his lot The Action; The La De Da’s lived there ... Larry’s Rebels stayed there; Barry Leef lived there; Australian bands like the Masters Apprentices lived there too.”

Evan Silva with Mike Wilson's guitar in the Plaza Hotel, Sydney. - Evan Silva Collection

There was a huge contrast between those who loved it and others who hated it. Evan Silva recalled, “Oh boy, the Plaza was ‘the joint’ ... I was okay with it as I’d been a troubled teen on the streets in Mission Bay when I was 16.” He described himself back then as a stroppy youth who had to do six months of periodic detention in Auckland for assault.

Mick Leyton: “It was magic. I lived there for nearly a year on and off. $12 a week for a room with a double bed. $12 a week and that included a hot cooked breakfast at the hotel over the road. Egg and bacon. So you scoffed up large in the morning, went home with pockets full of rolls.” He giggled before he added, “And anything you could cram in them.” He giggled again and continued. “Bits of bacon. Twelve bucks a week; bed and breakfast. Beautiful. And on the top floor were all the wrestlers that used to work at the Sydney Stadium, so there was never any trouble ... I had a lovely room with a double bed, and I was on my own. Most of the rooms were not big. They had twin beds. And there was no bathroom. The bathroom was up the hall. There was nowhere to wash. You’d go to the laundromat down the block, but that was all acceptable.”

Larry’s Rebels first came to Sydney in 1967. John Williams recalled, “In that era it was all sleaze, like the Plaza in Kings Cross. All the bands used to go there. I just thought it was the creepiest, freakiest, sleaziest, most horrible place.”

Mick Leyton acknowledged the Cross was sleazy: “It was. It was colourful and sleazy, and it was alive. It was wonderful. You could get up in the middle of the night and walk out and it was happening. There was a girl on every corner. But they were lovely. We used to get on like a ’ouse on fire. There was no hanky-panky ’cause they were working.”

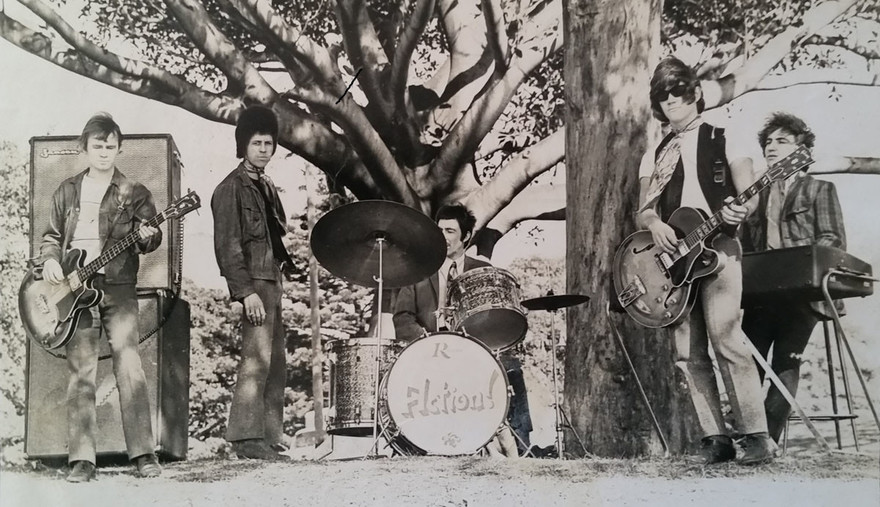

Retaliation with Phil Pritchard, Nicky Bagnall, Barry Leef and Mike Darby, about to head to Melbourne and Sydney in 1969

Barry Leef, who first went to Sydney in 1969 with Retaliation (before re-joining The Simple Image), commented, “We stayed at the Plaza. Everyone stayed at the Plaza. It was good to be in a place where all the musicians were because that was where all the networking was done. So you’d find out what’s going on, who’s doing what, does anyone need a piano player ... It was absolutely brilliant. I lived there for two years. At the Plaza.” He laughed.

Mick Leyton: “It was social; the Plaza. Down the bottom there was the thing called the Village where Mario’s shop sold filled rolls and pizzas. There was a little bar round the corner.”

The Action, Sydney, 1969 (L-R): Gus Fenwick, Evan Silva, Brett Neilsen, Mike Wilson, John Bisset - Evan Silva Collection

Evan Silva: “At the Plaza there were different rooms for different people and different preferred intoxications ... She was wild, with the World Wrestling Federation wrestlers living there, and hookers outside ...” He spoke about who else was staying there: “Max and Meteors, The La De Da’s and many interstate bands. The Action dropped their first LSD trip in their room at the Plaza, then ventured out barefoot into the Village where people looked distorted and more... When I recruited Mike Wilson from New Zealand to replace the guitar player in The Action we celebrated with a couple of magnums of champers and beers, then opened the room window onto the Cross and threw the cans at the double-decker buses passing by. Yes, the police came ...”

Mick Leyton also spoke about throwing bottles out the window from the Plaza. One night he and the musicians he worked with found a huge bottle of champagne somewhere. At the hotel the contents were shared between five or six of them before someone threw the bottle out of the window. He laughed as he spoke: “It bounced off a bus and it didn’t break. Bounced off a bus. Went on to the road. I went down and got it. I had it for years.”

Evan observed that it was some of the very straight guys who had problems with the Plaza ’cause it offended them. But there is no doubt it had a vibrancy and diversity. Mick again: “I was there the day the Cross changed. It was a big day and nobody remembered it. We all used to socialise ... We used to come out of the Plaza and the whole place was surrounded by a low brick wall. Everyone would sit there and smoke the odd joint and chat ... One day the council came round and put up little spikes on the wall. All the way round. So you couldn’t sit anymore, and the place changed overnight. Nobody knows that story. I was there and I saw it, and I thought, ‘What a mean thing to do’. It spoilt an immense social thing in Sydney. Just ruined ...”

In the 1970s a new breed of musician lived at the Plaza. Don Walker (Cold Chisel) lived there for years from the late 70s. He described the rooms as “small and ancient” with a shared bathroom on each floor. The working girls had been moved on by then, and he noted the guests there were primarily men down on their luck.

I’ll leave the final words about the Plaza Hotel during the 60s to Evan Silva. “It was a thriving dive ... I can understand why some struggled with it. It never stopped.”

--

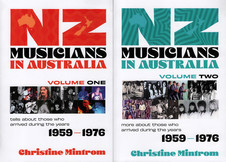

An excerpt from Christine Mintrom's encyclopaedic two-volume work New Zealand Musicians in Australia, which she published late in 2024. The books cover the years 1959-1976, the period Christine has often written about for AudioCulture. The books are based on dozens of interviews with musicians, and dedicated research in secondary sources. Mintrom, originally from Taranaki, and based in Australia for decades, wrote the biography Tommy Adderley (1940-1993), published in 2004. The two-volume New Zealand Musicians in Australia is currently available through Amazon Australia, as hard-copy books or on Kindle. Christine blogs at Kiwi Musicians in Oz.