Straitjacket Fits formed out of the ashes of Doublehappys, the band fronted by Kaikorai Valley High classmates Shayne Carter and Wayne Elsey in the early 1980s, with Elsey’s friend John Collie replacing their notoriously bad drum machine, “Herbie F***face”.

Shayne Carter confirms that Herbie wasn’t named after anyone. “We called it that because we could never figure out how to turn him off – he was a very problematic character,” he laughs. “We would try to stop it, but it would descend into a different beat, so you’d get samba thundering through the PA, or a bossa nova.”

After Elsey’s tragic death in 1985, Carter and Collie carried on.

“We kind of agreed some time after Wayne’s death that we’d do something together, and Straitjacket Fits was that thing,” says Collie.

Carter views it as determinism. “Wayne’s death really galvanised John and I as far as continuing to play music. One of the lessons out of what happened with Wayne was you gotta do what you wanna do, while you’re here to do it.”

Taking some time out, Carter recorded an elegy of sorts for Elsey, ‘Randolph’s Going Home’ with Peter Jefferies, and later he and Collie played with local supergroup The Weeds, infamously performing at the Dunedin Town Hall in their underpants. “A career highlight,” Carter dryly notes.

The following year, Carter and Collie regrouped with bassist David Wood (formerly of Working with Walt), and formed Straitjacket Fits.

The following year, Carter and Collie regrouped with bassist David Wood (formerly of Working with Walt), and formed Straitjacket Fits. Wood appeared on Carter’s George Street doorstep on the encouragement of Sneaky Feelings’ David Pine,who then worked at Dunedin’s George Street EMI music shop. The alchemy was there, and their first gig was a lunchtime performance at the University of Otago, supporting the Sneaky Feelings.

According to David Wood (NZ Herald, 2005), John Collie kicked the Sneakys’ drum kit offstage. However, both Collie and Carter deny this occurred. “I would never have done that,” Collie says. “The drum kit just fell over. It was this really shitty kit. Problem was for me that I was pretty much always hitting the things as hard as I could just to hear myself, so the kit would just slowly move away from me!” Carter admits to little recollection of the gig, but says “I think it just fell off … we were on a makeshift stage.”

In late 1986, Andrew Brough (ex-The Orange) joined the trio. “My flatmate at the time, Bruce Russell suggested Broughy. I can remember hearing David’s backing vocals for the first time and it was like ‘what is that horrible noise?” Carter laughs. “Dunedin’s a small place so everyone knows everyone. A very good singer, Andrew! I think we recognised straight away, that there were two pretty good singers in the band.”

Wood agreed, telling New Zealand Herald, “Andrew can sing like a fucking choir boy ... he was a pretty good guitarist too.”

Collie concurs. “Andrew definitely added a melodic sense to the band, but right from the start really there was this feeling that Andrew’s songs were a bit wimpy! However, it did work and created interesting tension in the music.”

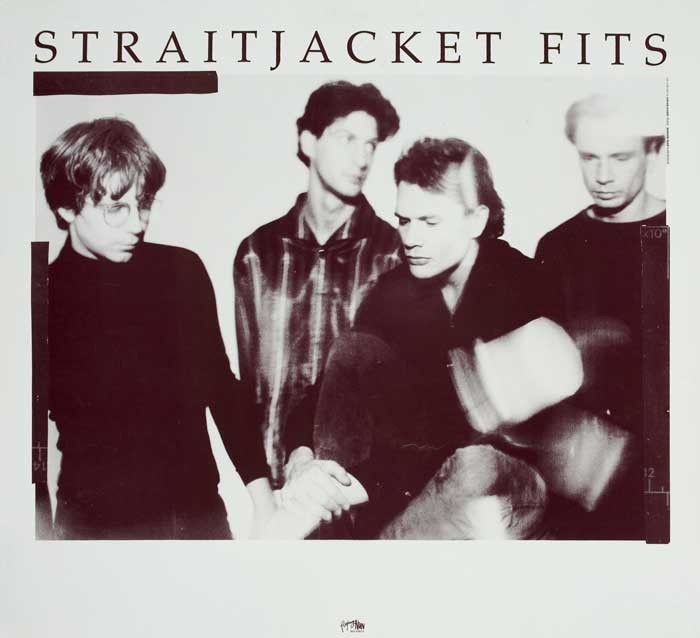

Straitjacket Fits' first gig at Chippendale House, 1986 - Photo by Jeff Harford

Straitjacket Fits’ first gig as a quartet was in October 1986 at Chippendale House, an afternoon gig Brough describes as “rough and ready”.

They signed to Flying Nun in 1987, with manager Debbi Gibbs involved in what Roger Shepherd termed “rigorous negotiations”. Carter and Collie had been linked to Flying Nun since the Bored Games/ Doublehappys days, and by the end of the decade certainly saw Straitjacket Fits (along with The Chills) as a leading light on the label roster, something that aligned with their levels of ambition.

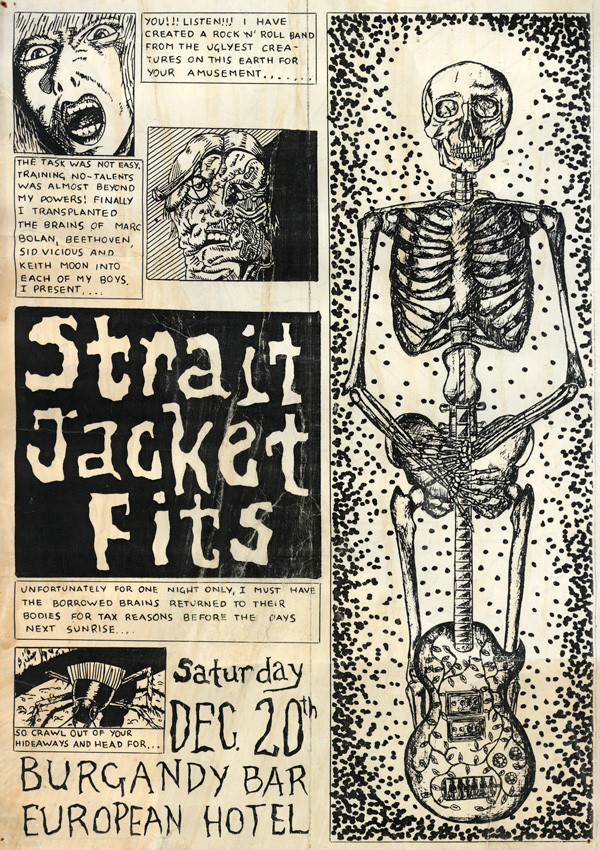

Straitjacket Fits at The Burgundy Bar, European Hotel, Dunedin, December 1986

Carter is realistic about the band’s relationship with Flying Nun, diplomatically saying it was “Up and down. Love Roger, he’s a great guy … [but he] wasn’t the most conscientious or the most efficient record company boss.”

1987 also marked the quartet’s debut EP, Life In One Chord, recorded at The Lab in Symonds Street, Auckland. With sometime Chill Terry Moore producing, the band took the four songs that worked best live into the recording studio.

While they were a guitar band, there was little of the jangle that identified the earlier Dunedin releases from The Chills or The Clean. Life in One Chord still stands as a startling first recording, and the guitar work sets out the band’s sonic manifesto – brash, melodic, and forceful. It’s most apparent in Carter’s songs ‘Dialling a Prayer’ and ‘She Speeds’, two instant classics.

‘Dialling a Prayer’ in particular is important for both Carter, and Brough, who anchors the song’s swirling vortex of energy with his harmonies. “I just think it’s one of the most rocking tunes I’ve written.” Carter enthuses. “I really like the inventive guitars in it – it’s got some fucked-up guitars in it. I love guitars like that.”

‘She Speeds’ is another beast altogether. Collie thinks its appeal lies in the unusual hook (“ ‘She Speeds’ – what is that?”) and says the volume dynamics in the song provide tension and release. The song marks out Carter’s strong streak of romanticism– something he agrees with. “I’m totally a romantic, I don’t mean in the affairs of the heart … but as far as sensibilities go, I love that shit!”

The song also has the distinction of Carter coming up with the chorus on the way to the Pine Hill Dairy. “Very happy with that! I remember that distinctly,” he smiles. “That was one that people picked up on. I didn’t put any more work, or any less work into that tune, than I put into any of my other ones.”

‘She Speeds’ made those in the know take notice of the band from day one.

‘She Speeds’ made those in the know take notice of the band from day one. Otago Daily Times reporter Sean Flaherty described the song in ecstatic terms, saying it “builds into an amphetamine rush, speeding in angry bravado before subsidizing to fake bathos … then, more guitar thrills, choir boy harmonies and a suitable fadeout.” The plaudits for Life In One Chord kept piling up, with Australian music weekly On the Street calling it “arguably the greatest debut single of all time.”

Brough considers Life in One Chord to be indicative of the band’s live performances, which were never accurately captured in the studio. “Definitely ‘She Speeds’ on the first EP captures the live [sound], but the first album didn’t.”

His own track on the EP, ‘Sparkle that Shines’ was another highlight, but he is critical of his vocal performance. “I don’t like the singing so much on [‘Sparkle That Shines’] because it’s quite pompous and young. I could sing it a lot better now. I remember in the studio when it was coming together, you could tell that it was going to work.”

Carter remembers the recording process as being direct. “We didn’t really fart around. We didn’t really know what we had, but it was something!”

Life in One Chord gave the foursome their first taste of success, spending 10 weeks in the NZ Top 20, and reaching No.16 on the Singles Chart.

‘She Speeds’ is considered a bona fide classic, voted in the top 10 of APRA’s top 100 NZ songs of all time. However, Carter has a bone to pick with the creators of the Nature’s Best sheet music book. “The version of that song is an abomination … every lyric, every line is completely wrong, it’s this nonsensical ramble of phonetic sounding words, which don’t actually make any sense at all. How fucking slack is that?”

After releasing Life in One Chord, the band moved to Auckland to record their debut album, Hail. Hoping that lightning would strike twice, they again used The Lab Recording Studio and Terry Moore. This time, the results weren’t entirely what they wanted.

“The Hail record, it was a real disappointment,” says Brough. “My attitude was we’ve done an EP with four songs, now we’ll just do it with twelve, but it just didn’t turn out that way.”

He puts the difference down to a couple of things. “It’s a comedown – there’s no ‘She Speeds’. That could have been an issue, but there’s enough to work with to make it a better album. It didn’t come to fruition musically. It wasn’t something I was proud of. The first EP, I was really proud of. I was thinking, ‘Shit, I’m on that! I was part of that’, it was good.”

Carter also remembers Hail being difficult to record, and thinks the album disappointed the band. “The EP had been strong, and I think we used our best songs on [it]. There’s still some good songs on the album.”

Collie too has a negative reminiscence of the experience, as there were “Lots of technical hassles in the studio and trying to drum to a click track … it shows.”

Hail was released in 1988. It didn’t chart, but created more buzz around the group, with positive notes from the international music press, especially in the UK, something Carter says was “kind of nice, but… I think we were too down on ourselves to get egotistical about it!”

Rough Trade released Hail in the UK and US late in 1988, with a different track listing, adding the four songs from Life in One Chord, and removing tracks that hadn’t worked on the original local release.

“I remember that coming out,” says Brough. “I did two songs on that Hail record, and I didn’t like either of them very much. The one on the first EP, ‘Sparkle’ came out really well, and I thought ‘this is where I want to go.’ I wanted to do more of that, make them sound like that.”

The local response to Hail was mostly positive as well. Writing in NZ Listener, Lisa Van Der Aarde described the the sound as “too even, and some songs fall flat,” though she confirmed “musically this LP is strong.”

When interviewed by RipItUp in 1988, the band expressed frustration with the lack of control over recording, Carter telling Angela Jonasson, “As a musician, it’s your band, your sound, and your music, fuck it, so you want an element of control over it.”

By this time, the band was also talking about their style as an amalgam of influences. “We’re using guitars, and trying to use them to their maximum,” Carter continued. “We deal in songs, not sound sketches or funky grooves.”

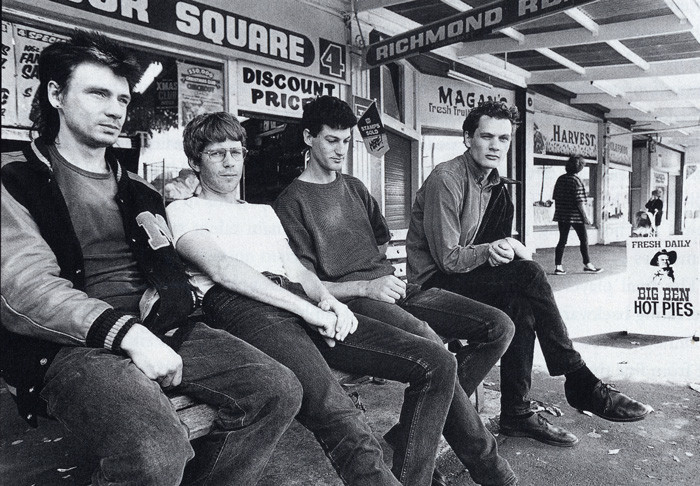

Straitjacket Fits on tour, in Palmerston North - Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena – University of Otago

After playing locally in Dunedin and travelling to Auckland for gigs, 1989 was the year of Straitjacket Fits’ first overseas tour. Deciding to forego Australia and the UK, they headed to the USA and then Europe, playing the European leg as a double bill with American band Galaxie 500. Rough Trade supported the tour, as after releasing Life in One Chord in Europe there was a substantial buzz around them.

Brough remembers the US fondly. “For me it was just a big holiday, to see the world. I was so into American movies and American culture, that actually going there … you were in the movie! That was the thing about LA, and New York City ... It didn’t bother me if we didn’t have a good gig or not, we were there, doing it! I went to Disneyland, I remember the day, we almost didn’t go, and I almost had a temper tantrum!”

Carter has one word to describe the experience: “Surreal”. “I can remember, the first thing that happened when we arrived in Los Angeles … [there’s a guy from] Motley Crue going past on a big Harley Davidson motorbike! Yeah, that whole time was very surreal, a great adventure.”

Brough liked the gig set-ups too. “Part of it was to do with that we had a good venue: high stage, good setup. A lot of the venues we played were quite pokey, and you’d feel like you were a bit cramped. I remember one in San Francisco was great, we drove all that way from LA just for one night, and it was a big crowd, five hundred or so. CBGB’s in New York, that was the most important one, that was quite good. That went off.”

Carter is also a fan of the CBGB’s gig, saying, “The first time we ever played CBGB’s, our first time overseas, we went over and killed it!”

Listening to the live tape of that CBGB’s gig, they are both right – the band is firing on all cylinders. They sound tight, and raw: initially tentative, as if they are feeling their way around the crowd’s expectations. The audience becomes more appreciative as the gig goes on, the applause growing louder. Both Carter and Brough are in fine voice, harmonically in sync. The performance gets more intense, confident, and swaggering as the show goes on, and by the final track, ‘Hail’, they roar.

By this time, Straitjacket Fits were contenders for the title of best band in the world.

By this time, Straitjacket Fits were contenders for the title of best band in the world. Their long-standing fans knew this (the band had an inkling of this themselves), and the music world was waking up to it as well, with Melody Maker writing in 1992, “They’re the weirdest guitar band in the world. They’re also the best.”

Small steps first: at the end of 1989, they signed a six-album deal with Arista Records on the back of alternative music stepping more into the mainstream. However, the band didn’t fit the Arista mould, and inevitably, the relationship between band and label deteriorated, as they were overwhelmed by the juggernaut of grunge, and refused to sell out their principles for money and fame.

Carter is still disgruntled about the Arista experience. “We were pretty blasé about it. We’d already dealt with international labels. Rough Trade were obviously a lot more on to it, aesthetics-wise, than Arista were – Arista didn’t have a fucking clue. There’s many great things about the Arista story – the A&R guy who signed us went on national TV here, saying ‘yeah, Shayne Carter is an amazing performer’ – he’d never seen us play live! It was a pretty conservative record company – we certainly didn’t get each other. When we signed with them, it actually worked against us; we weren’t taken seriously because we were on a major label. I don’t think they had a clue what they wanted us to be. We’re these sort of punk rock kids, from fuckin’ Dunedin, and they’re these New York high flyers who can’t understand why you won’t do anything to be famous".

Brough, contrarily, remembers it positively. “It was really, really exciting, just another step in the right direction. The second tour with the Arista deal, we got much better gigs, much better accommodation, more money, you know you could see how you could live a life like that at the time. I remember when we went back, I didn’t want to be poor again, like we were the first time. It was good to be looked after and have the record company behind you, though in retrospect, they didn’t turn out to be the right record company for us!”

Collie considers the irony. “It was pretty awesome being on the same label as Whitney Houston and Kenny G (well not really)!” He does admit to the benefits of being signed to the major label. “We had some great times in New York and played some pretty special gigs we wouldn’t have done otherwise. We got tour support to play in the US and of course we recorded Blow [their final album, 1993] in LA which was just another level in terms of studio quality. It was a great way to do your OE.”

Straitjacket Fits around 1990: David Wood, Andrew Brough, John Collie and Shayne Carter

On returning home, the band recorded their second album, Melt, in July and August 1990 at Airforce Studios in Auckland and Platinum Studios in Australia. Melt was produced by Gavin MacKillop (who had worked with Human League, Public Image Ltd, Echo and the Bunnymen among others), and all the band consider it the best album they made, and one that represented their sound best on disc.

Carter still agrees. “I’d still say it’s seventy percent. There are still songs that were really good live songs, but didn’t really work. Maybe over reverbed, and over produced, but it still has got some genuinely good songs too. So, that is probably our most successful studio record. Once again, I can diss all of our records!”

A relatively big-name producer, Englishman MacKillop (who later produced The Chills’ Soft Bomb) didn’t tell the band how to play their music. Rather, Carter told Critic in 1990, “It was a matter of consultation rather than dictation.”

Melt was rumoured to have a large budget, with a “million dollars” mentioned, which Carter says was ridiculous, as the budget was “considerably less than the unbelievable amounts which we heard.” The amount, he told Critic, was average for a debut album, but they were in the spotlight, as the first band to record a big album under Flying Nun’s (then new) agreement with Mushroom Records.

Whatever the budget, though, it didn’t change the music. “It’s probably got a sheen that a lot of Flying Nun stuff hasn’t got. But it’s still our music played really well,” says Carter.

“I’m glad we did Melt,” Brough states. “You know, I’d go straight to Melt as a better example of what we were about. A lot of money spent on it, quite a professional engineer, and a professional studio. And, Shayne was definitely on top of his game.”

Collie has good memories of recording Melt. “The whole experience of working with an overseas producer who really knew how to draw out a performance and keeping things as fresh as possible was great … Melt caught the band at a good time I think.”

Melt wasn’t without its critics: Gary Steel, reviewing it for NZ Listener, called it “Infuriating and inconsistent”, although he added “At its best … stuns the senses and leads the way to future world domination … if they don’t break up first”

Melt was a local success, No.13 on the album charts, ultimately selling 40,000 copies in the USA. Three singles were released from the album, ‘Bad Note for a Heart’, ‘Down in Splendour’, and ‘Roller Ride’. Of these, only ‘Bad Note for a Heart’ troubled the charts, but ‘Down in Splendour’ stood out, and was also eventually included in the APRA Top 100 New Zealand songs.

Straitjacket Fits: Shayne Carter, David Wood, Andrew Brough and John Collie

Unlike the other singles, ‘Down in Splendour’ was arguably aimed squarely at commercial radio, as it was the most radio and record company friendly track on the album. As Carter admitted to Critic, “A single, like it or not, is an advertisement for the album. If it gets across to a wider audience, then for sure.”

‘Bad Note for a Heart’, however, did win the best music video at the 1990 NZ Music Awards. Directed by Niki Caro, the video is rich in symbolism, with tightly framed shots and Carter sporting some beautiful eye shadow, something he was derisive of. “After the ‘Bad Note’ video we will never be wearing lipstick, eyeshadow, or anything else ever again. That was definitely a low point in rock,” he told RipItUp in 1992, while laughing to Wendy Yee at Kahoutek ‘zine, “it was a particularly low point in my life.”

Concurrently, Straitjacket Fits became the pin-up boys for Flying Nun, injecting sexiness into the Dunedin scene especially, something it wasn’t known for at all.

“Some of the bands were a bit … asexual, if that’s the right word,” says Brough. “I didn’t think The Clean were all that sexy! So, we wrote songs about having sex, and girls, and that’s what they were all about.”

Carter in particular became a poster boy for the band. The camera loved his pouting, brooding, cheek-boned good looks, and his sneer. Did the band’s smouldering good looks get them into interesting situations? Carter laughs at this, and perhaps chooses his words wisely. “I discovered we were actually a pretty well behaved band … we had more class than that. We were always far too self-conscious and pathetic to go strutting.”

By now, Straitjacket Fits were one of the preeminent rock bands on Flying Nun, and more widely, in New Zealand. Did this bring pressures?

“Yes,” says Collie. “Flying Nun had all these bands that were demanding a lot in terms of money for recording, touring and promotion, and there was not a lot of money coming in from sales that was going to cover those costs. We did quite well out of the hook-up with Mushroom Records and then later when signing to Arista, but again, there were not enough sales.”

Carter concurs. “The more successful we got, the more people are around you going poke, poke, poke, ‘you should do this, you should do that’. Invariably, the people in bands who are successful are young people, and so they’ve got these people around them going ‘no, do this, do that’. These are people who stand around and say things so they can go home to their family, and say ‘I told this person to do that’. I’m not dissing everyone in the record industry, I’ve met some wonderful people, but they all have a frame of reference, and it’s the creative person who is usually standing beyond that frame of reference. That is the difference between the artist, and the people who control their careers. All those people, whether it’s the people who make all the money, or the lawyers, or the record company people, or whatever, you know?

“It’s a real test of character actually, and to maintain the faith. Being a creative person is quite a pure thing to aspire to do. The peripheral stuff is bullshit, usually, and it’s got nothing to do with your creative intent, and all the purity of playing music, you know when you play music it’s such a pure thing to do.”

Straitjacket Fits also found themselves at the end of criticism at home for not touring locally enough, though they did university orientation shows around New Zealand for four years in a row. Carter told Wendy Yee that it was down to a backlash.

“I think we’ve come full circle in that we’ve started off as the new hip new things for a while, and then for a while we fell out of fashion … because we were getting a bit too big … for that reason it can be really refreshing to get out and play overseas, because people aren’t nit-picky, they just see it for what it is.”

--