Christchurch has long had a reputation as a dull and conservative place, though there has always been a cultural undercurrent that cuts at that premise. The city has a proud musical tradition, playing a critical role in the development of bands and singers such as Max Merritt, Ray Columbus, and Dinah Lee in the 1950s and 60s. In the early 80s the Flying Nun label was founded in the city, and around the same time the Dance Exponents moved up from Timaru and were honing their sound with residencies at pubs including the Hillsborough Tavern. Salmonella Dub, formed in Christchurch in the early 90s, were the progenitors of the dub sound that would shift its centre to Wellington in the next decade, while Shapeshifter took drum and bass from the clubs of Lichfield St and made it a mainstay of the summer festival circuit. My old high school, Cashmere High, produced three very different mainstream successes, with Bic Runga, Zed, and Yulia all having albums that topped the New Zealand chart.

But in the first few years of the new millennium, Christchurch had a vibrant indie scene that blew against the prevailing musical winds. At the same time that indie music was moving from the bedrooms and blogs to the main stages of festivals all across the country and the world, artists in Christchurch were putting out some of the best music to come from the city in a long time.

Of course, it didn’t just come out of nowhere. A strong DIY and underground alternative scene had been active in the city through the 90s, making use of the cheap spaces on the fringes of the CBD, and utilising recording and distribution methods that would come to democratise music production in the following decade. Around the same time, dance music was taking over the city nightclubs. A generation who grew up in this time would bring together all these disparate elements, and bands such as The Shocking Pinks, Pig Out, the Tiger Tones, and Bang! Bang! Eche! emerged from this scene to find national and international acclaim.

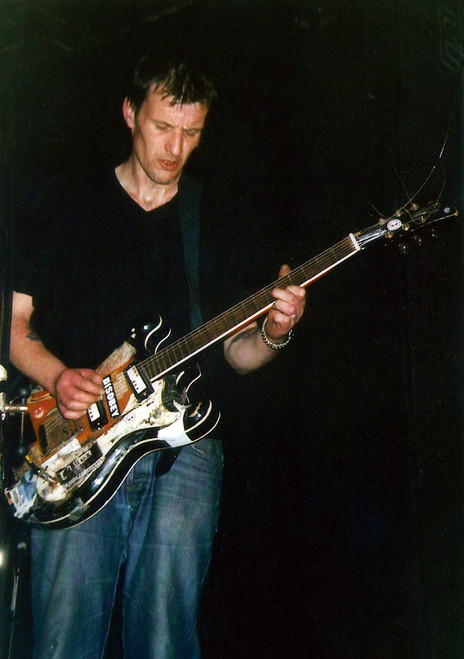

Nick Harte from the Shocking Pinks, December 2007. - Chris Andrews

While this burst of creative activity had largely petered out by 2010, this period saw the release of some excellent music, the rise and fall of some challenging, electric, unpredictable live acts, and some iconic shows at iconic venues. When the quakes struck in 2010 and 2011, wiping many of these venues off the map, it provided a hard end-point for a scene that had already run out of steam.

I was studying in Dunedin when the first Shocking Pinks album came out in 2004, alerting me to the existence of something special happening back up the road. Having been away from Christchurch since I was at school, I moved back there, and started to get quite involved in the music scene. I wrote and performed music under the name Ed Muzik from about 2005 onwards, including playing gigs at many of the venues listed, and with many of the bands I’ve featured. I’ve tried not to include anything about Ed Muzik, but much of my understanding for this piece comes from being involved, at least on the periphery.

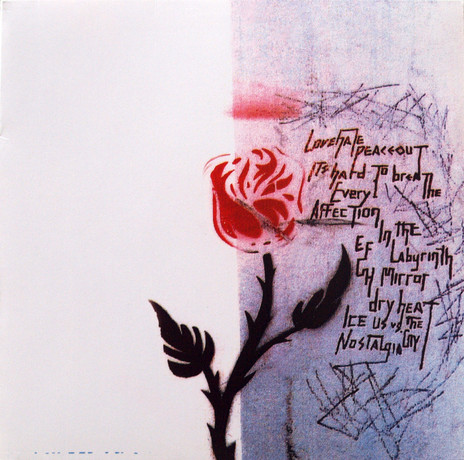

Cover of the Shocking Pinks’ album, Dance the Dance Electric. - James Dann

Despite its Garden City image, much of the most interesting art come out of Christchurch has been what some might consider weeds. The home of the Flying Nun record label, there had always been a strong connection with the bands down the road in Dunedin. By the 90s, noise pioneer Bruce Russell (The Dead C) had moved to Lyttelton, and groups such as Into The Void and The Terminals would reappear from time-to-time, like the bogeyman in a Hammer Horror film.

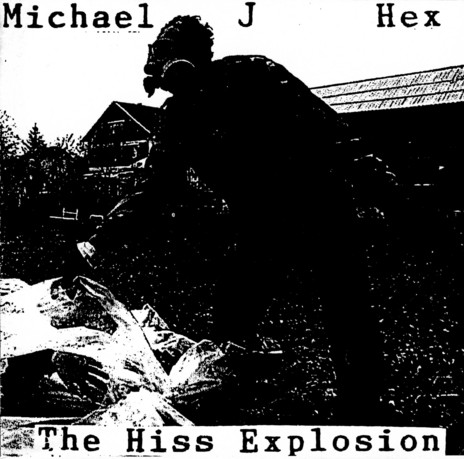

One of the most significant figures in the evolving DIY scene at this time was Michael Brassel, aka Michael J Hex. After a brief stint in Sydney, he returned to Christchurch in the late 80s, and in the early 90s formed Squirm. To quote their record label, Failsafe Records, “Squirm was born in 1992 when two friends Virgil Reality and Mike Hex joined forces with a rather anarchic drum-thrashing accountant named Hat to form a ‘Progressive Art Punk Glam Rock Band’.” Squirm played up and down the country, releasing an EP and an album with which they quickly made themselves a name. “There are songs with no drums, some with no bass, some with samples, and some with organ, but always it seems there are guitars. If comparisons are called for, try Sonic Youth meeting The Fall in a gin-soaked garage somewhere in central Christchurch.”

Michael J Hex, Christchurch 2004 - Roslyn Njenhuis

Another group which embraced the lo-fi aesthetic was Space Dust. Formed by Duane Zakarov (real name, Pat Faigan), Space Dust was one of those groups with a list of band members that looks more like a phone book. The core group formed around Zakarov, his sister Violet, Mick El Borado, Brother Love, and John Chrisstoffels. In 1995 they released two albums on two different American independent labels: Beatle! on 18 Wheeler, and First To The Future on Carburetor Records. Others who played in the band included Matt Middleton (aka Dunedin’s Crude), and on organ, Annabel Alpers. Alpers would then go on to form Hawaii Five-0, with Caleb McCullogh and Paul Ward. They were known around Christchurch for their catchy singles and rich organ sound. They released a couple of singles on the Beat Atlas imprint, lathe cut by the legendary Peter King.

Michael J Hex moved on from Squirm to play and release music under this name. With his flat-cum-venue-cum recording studio, Hex Central, his DIY recording ethos was a key influence on the next wave of bands. In 1998 he released the album The Hiss Explosion, a name that he would go on to use as his own artist name. He moved to Dunedin in the late 90s, and in 2002 he teamed up with ex-Squirm drummer Peter Mitchell to record the album 66, released by the Hiss Explosion on ArcLife. He often returned to Christchurch, including playing a show on Waitangi Day, 2004. He sadly died later that month, and the two concerts that were put on in Dunedin and Christchurch in his memory showed the influence he had on his peers, with bands such as Into the Void, The Undercurrents, and the Shocking Pinks playing.

Michael J Hex, The Hiss Explosion, Noseflute 1998

While Christchurch would later become known for having a healthy drum and bass scene, at the turn of the century it hosted a variety of dance clubs which played all sorts of underground music. Clubs including Heaven and Base skewed more towards house, prog house, and trance, while larger venues such as Hybrid and the Ministry would open up for the bigger international DJs. There was a wave of bands that associated more with the dance scene than the rock scene, including Shapeshifter, Verse 2, and Solaa. The latter formed in 1997, and developed a strong reputation for their fusion of house, funk, and soul in a live setting.

Tim Baird from Pinacolada recalls them as some as his favourite gigs: “I’d have to say some of the Solaa gigs at the now-demolished Base bar on Colombo Street around 1999/2000 were pretty instrumental in getting me thinking about starting the label. There was a lot of cross-pollination amongst musicians, DJs and genres at the time, and these gigs were like a melting pot of all these creative minds and ideas.” Though the divide between club kids and indie kids always seemed to be hard and fast, the influence of dance music on the records that came out is now obvious.

The record that synthesised all of these disparate elements was Dance The Dance Electric (2004) by The Shocking Pinks, and the man who embodied all of those idiosyncrasies was Nick Harte. Formerly known as Nick Hodgson, he had been dabbling in music since school, releasing cassettes on the kRkRkRkR label as far back as 1995. These were mainly free-form experimental releases, recorded either solo, or with collaborators, under his own name or various other monikers, including Montessouri, Crone, CM Ensemble, Hiatus, and others. Around 2000 he was in a long list of heavy guitar bands, including the Incisions, the Urinators, and the Hi-Tone Destroyers, as well as a time in Solaa. Tim Baird recalls that Hodgson got banned from calling student radio station RDU after winning too many prizes. He left Christchurch to join the Auckland-based Brunettes, and was part of their tour to England in mid-2003. James Milne, aka Lawrence Arabia – also from Christchurch – remembers that he and Nick went and saw the New York dance-punk band The Rapture play on a night off. When the tour was over, Hodgson, now Harte, returned to Christchurch where he formed The Shocking Pinks.

Get Set Play (solo project of Mark Holland in the centre; from Tiger Tones) with Blink on the mic and Nick Harte (Shocking Pinks) on drums, Camp A Low Hum 2007.

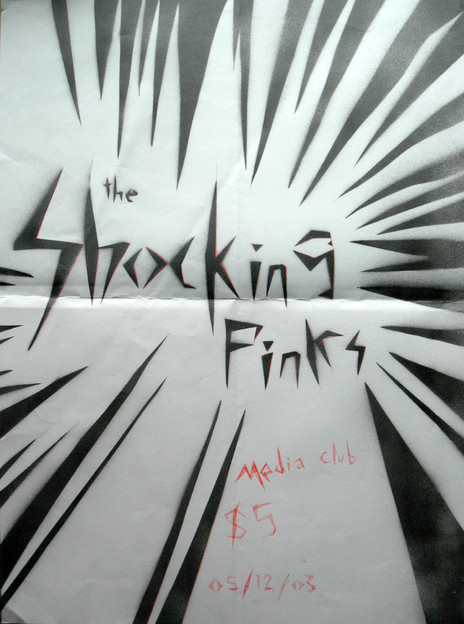

The Shocking Pinks quickly made quite a name for themselves. Baird, who had known Nick from his dealings at RDU and Galaxy Records, went to see them at the Media Club in late 2003. “I went along, and within two songs I knew that they were great and that someone needed to get this out as soon as possible.” Baird suggested to Nick that he would put out their album on his record label. “Nick dropped a copy of the album in to the shop the following Monday, and I said I’d front the money to get it out, so he agreed to do the album with us. The master was winging its way to the pressing plant in Sydney by the Wednesday of that week.”

The record label in question was Pinacolada. Baird founded Pinacolada in September 2001, while working at Galaxy Records. He’d had a long involvement in the music scene in the city, including his role at Galaxy Records, and previous roles at RDU. He started the label to release local music on vinyl. The first release was a 12" single from Rockwood, aka Pete Wood from Salmonella Dub, then followed by a full-length Rockwood album, The Tripper’s Guide to House.

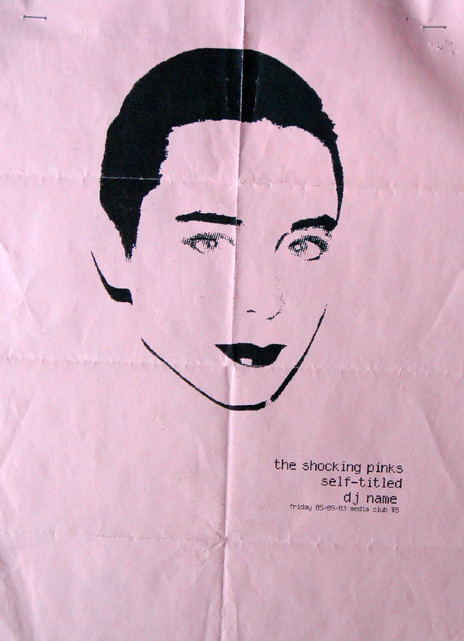

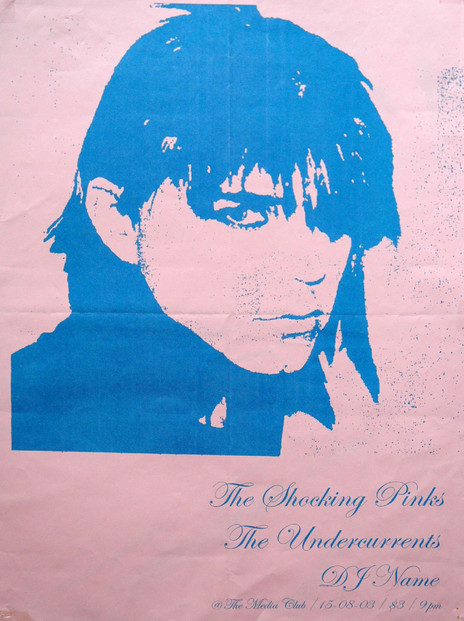

Poster for Shocking Pinks gig at the Media Club, December 5th, 2003 (the gig which inspired Tim Baird to sign the band to Pinacolada). - Chris Andrews

Two more releases reinforced the dance credentials of the label, so signing the Shocking Pinks was something of a departure. These other releases included a 12" from Thisinformation featuring Mark de Clive-Lowe (Thisinformation was a duo formed by Chris Cox and Isaac Aesili, also in Solaa). However, with the success of Dance the Dance Electric, Pinacolada became the most important label in this nascent scene, a reputation enshrined by their two subsequent releases.

Combining his years of performing in experimental groups and distorted live bands with a proto-disco beat and almost emo lyrics, Dance the Dance Electric got the attention it deserved. On the record, Harte does most things, but the core of songs also feature Jonno Smith on bass and Tim McDonald on drums, percussion or synth. Kurt Dyer – who played with Harte in Solaa – plays congas on a couple of tracks, and the final three songs feature guest vocals from three different women: Antonia De Vere on ‘Dry Heat’, Mel Smith from the Greenmatics on the iconic ‘Us Against The City’, and Heather Mansfield from The Brunettes on ‘Nostalgia’.

‘Affection’ is perhaps the best example of the more upbeat Shocking Pinks songs from this period. An extended intro, built around a rollicking bass line, supplemented with washes of guitar, before the disarmingly stark lyrics about a girl in a record store, which end with “then one day I asked her out / she said yes / we broke up two months later / oh, but we gave it our best”.

Poster for a Shocking Pinks gig at the Media Club, September 2003. - Chris Andrews

Somehow it found its way to someone at Pitchfork in the US, where it had received an 8.2 review score (still one of the highest scores the website has given to a New Zealand artist): “Dance the Dance Electric, the group’s debut full-length, would blend inconspicuously into the emergent dance-punk section of any hipper-than-thou record store – that is, until an unsuspecting store clerk actually bothered to spin the disc, whereupon it would be revealed as a sophisticated collection of casual genre-hoppers and tender love songs that far outshines most of the bilge spawned from James Murphy’s Chernobyl-like fallout. Dance the Dance Electric is simultaneously one of the most tragically hip and irreverently unaffiliated records of the year, cavorting from unabashed disco revivalism to scuzzed-out new-wave to reggae-tinged psychedelia in a mottled kaleidoscope of brazen idealism.”

The review also placed The Shocking Pinks in the context of influential NYC record label DFA Records and its output such as LCD Soundsystem and The Rapture – the band that Harte had seen in London less than a year earlier. No one quite knows how Pitchfork got hold of the record, but Baird’s theory is that “an American tourist bought a copy in Galaxy Records and passed it on to them. We certainly didn’t send it to them. I was as surprised as everyone else when it appeared on the Pitchfork site with a glowing 8.2/10 review – it was also the same week that Franz Ferdinand released their debut album, and that got a 7.5 out of 10! My email blew up – everyone wanted to know who this band were.”

Poster for the first Shocking Pinks gig at the Media Club, August 2003. - Chris Andrews

Dance the Dance Electric was released on Valentine’s Day – 14 February 2004 – but between the album being sent to the presses and the release date, the Shocking Pinks broke up. Or at least, the “original” Shocking Pinks broke up, but fans and detractors alike quickly came to realise that the only constant in the Shocking Pinks was Nick Harte.

For the next couple of years, seeing the band play live was a bit of a lottery. They were known for their energetic, distorted and danceable sound – and there were live shows which captured this. But there were also totally shambolic shows, where Harte would turn up and play a CD from a Discman, or play an acoustic guitar, while half of the (former) band watched from the crowd. The first time I saw the band was at the Wunderbar in Lyttelton. There was no band to speak of. On stage was a guy playing tracks off a computer. This wasn’t a laptop computer, but a full desktop tower computer, resplendent in beige, with a CRT monitor. Harte stood on the dancefloor, wearing heavy dark shades, singing lyrics from a well-folded piece of paper. I left after three songs.

Though the live aspect was touch and go, the album itself was a borderline masterpiece, and the band’s reputation around the country was on the rise. The Shocking Pinks signed with Flying Nun, where they sat comfortably alongside contemporaries such as The Mint Chicks, as well as the more storied bands from the label’s history. Flying Nun released two Shocking Pinks albums in 2005: Mathematical Warfare and Infinity Land. Though there will still a couple of upbeat jams on these albums, they mainly moved away from the dance punk sound of the first album and towards well-crafted indie pop songs.

In 2007, The Shocking Pinks signed to DFA records, the New York label with which his output had been compared to ever since the debut record came out. DFA got busy releasing Harte’s music for the American market, with a self-titled record compiling some of the best songs from Mathematical Warfare and Infinity Land, as well as four single releases, which also came with remixes from high-profile artists. Sadly though, there was a never a full-length release of new material on DFA.

Nick Harte from the Shocking Pinks, November 2007. - Chris Andrews

When Harte signed on in 2007, DFA’s head-honcho James Murphy was busy with his band, LCD Soundsystem, touring in support of their second album Sound of Silver. Murphy may just have been too busy to focus on all the projects on the label, or distracted by the internal chaos at DFA, as documented by Lizzy Goodman in her book about the New York scene, Meet Me In The Bathroom. Harte had returned to Christchurch, and was working extensively on new material around the time of the quakes, often working for days on end. Though he had more than 300 completed tracks, these were eventually pared back to 45 for the triple album, Guilt Mirrors, released on another New York label, Stars and Mirrors. (The label was run by Mark Roberts, an American who had lived in Christchurch in the mid 2000s, writing and performing music as The Enright House, before returning to the States.)

A great number of people played in The Shocking Pinks band, including Kit Lawrence and Marie Celeste (Marie Paynter). Kit and Marie then went on to form House of Dolls, with Kris Taylor from the Leper Ballet. Taking their name from Joy Division’s song ‘No Love Lost’, House of Dolls had a darker, post-punk sound. They operated as a three-piece, with Taylor on drums, Celeste on synths, and Lawrence singing and switching from guitar to bass. They self-released two EPs, with the second a live recording of their show at the Dux de Lux on 27 October, 2005, hinting at the dancier direction they would soon take. House of Dolls soon became Pig Out, with the same core lineup (Kit Lawrence, Marie Celeste, Kris Taylor), often supplemented by extra vocalists or players.

Pig Out at the Dux De Lux, Kris Taylor on Drums, Marie Celeste on synths. - James Dann

According to their Soundcloud page, “Pig Out is a 2-5 piece live rave act that began by accident in 2006 whilst performing an impromptu show to raise funds for the temporary art space two of the members were running.” Eschewing some of the seriousness of House of Dolls, Pig Out borrowed heavily from both the sonic and visual aesthetic of late 80s and early 90s English rave. Their sound was definitely in vogue, with British acts like Goldfrapp, The Klaxons, and the New Young Pony Club loosely being grouped under the “new rave” banner. With Lawrence – who was born in the north of England – on the microphone, his English lilt certainly lent a bit of old-country legitimacy to the sound.

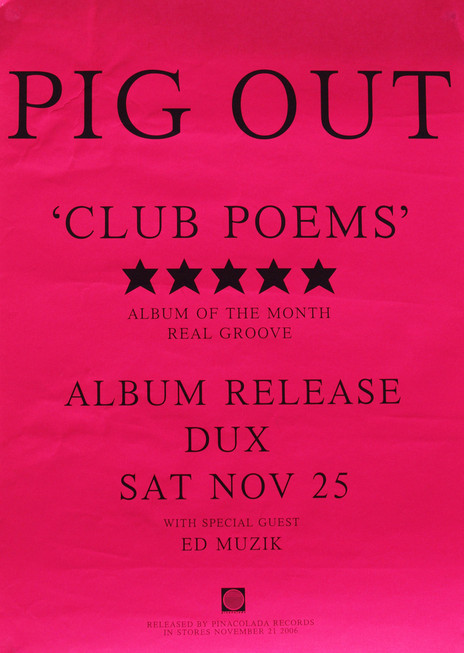

Tim Baird was a fan: “They played regularly at the old Dux de Lux at the Arts Centre in Christchurch, and their live performances drew really good crowds – it was also one of those times where the audience became part of the group live as maracas and tambourines got handed out to the crowd!” He signed them to Pinacolada, who released their debut album Club Poems in late 2006. “The album was recorded in their living room in Edgeware and mastered by Steve Fowler at Clevetown Studios in Christchurch. The release tour in support of the album, in November, 2006, was a blast; particularly the Auckland gig with Cut Off Your Hands at the Dogs Bollix. The Auckland art-school kids really embraced the band, which was great.”

Poster for Pig Out’s album release show at the Dux de Lux, 2006. - James Dann

Pig Out often featured someone playing live bass. Nick Harte played occasionally, but for some of their most memorable gigs it was Fraser Austin. Austin also had his own side-project, Frase and Bri. This was a duo of Frase and his partner Bri Yaakoup playing sad-wave pop songs. Frase had an insane collection of vintage gear, including computers from the 80s, that he had modified and adapted to create a unique palette of atmospheric synth pads and tinny drum beats. A favourite of Blink, Frase was a frequent presence on A Low Hum tours and parties, often alongside kindred spirit Disasteradio.

Another who found a voice in the sort of discarded electronics you might find in an op-shop was Bachelorette. Annabel Alpers, who had been in late-90s bands Hawaii Five-0, Space Dust, and The Hiss Explosion, had been absent from the scene for the first few years of the new millennium. After completing post-graduate studies in computer-based composition, she returned to playing music under the moniker Bachelorette in 2005. Her End of Things EP was released in August of 2005 on Arch Hill Recordings to widespread acclaim. One of the few collaborators on her first EP was Mick El Borado, whom she had played with in Space Dust. In 2006, she hid herself away in a small room in the middle of nowhere to record her first full-length album, Isolation Loops.

Annabel Alpers from Bachelorette performs at Al’s Bar, Christchurch, 2009. - Chris Andrews

She followed this up with two more albums, released on the US label Drag City: My Electric Family in 2009, and Bachelorette in 2011. These works had a wide reach, including a favourable review from the New York Times’ chief pop music critic, Jon Pareles: “The songs hint at girl groups, The Beatles, electro, ABBA and Minimalism; they often start simply and spiral outward like cotton candy in the making.”

Alpers now lives and works in Baltimore, and in 2017 successfully crowd-funded her next musical project. Though she wasn’t based in Christchurch at this time, her connections with bands from the 90s, and success both nationally and internationally, meant that her unique blend of warm, distorted, synthetic pop with a particularly Cantabrian brand of melancholia was an influence to many.

Many of these acts who were coming to prominence in 2004 and 2005 had musical histories that went back to the 90s. The next bands to come from Christchurch were much younger. In part two I’ll look at how the groups in this part were an inspiration to the ones who would step into the scene in the next couple of years.

Read Christchurch Indie: Us Against the City, part two

--