Johnny Devlin wows the crowd, 1959

For six months in 1958-1959 New Zealand witnessed an unprecedented level of teenage hysteria. There were headlines almost daily, parents and parliamentarians expressed outrage, policemen were injured, box-office records were broken, record sales went through the roof. This was The Johnny Devlin Show.

Devlin was already well-established by the time the tour kicked off. His meteoric rise had started in hometown Whanganui, before spreading around the lower North Island, culminating with a headlining performance at a rock’n’roll jamboree in a packed Wellington Town Hall in August 1957. During a visit to Auckland in January 1958 he was plucked by promoter Dave Dunningham for a residency at his Jive Centre venue, with occasional forays to Whangarei, Hamilton and other upper North Island towns.

Billed as “New Zealand’s Elvis Presley,” Devlin’s appearances at the Jive Centre and other venues attracted energetic and enthusiastic audiences, mostly full houses. Signed to Phil Warren’s Prestige Records, Devlin had released three singles by November 1958, with Warren claiming over 50,000 records sales. Momentum was building and Dunningham and Warren were already contemplating a national tour when the ideal opportunity presented itself.

Graham Dent was a genuine rock’n’roll fan. Two years earlier, as an 18-year-old trainee manager at Kerridge-Odeon, the national cinema chain, he had masterminded the promotion of the film Rock Around the Clock, which for most New Zealanders was their introduction to the new music. It was New Zealand’s highest-grossing film of the 1950s and, as a reward, Dent was appointed manager of the Point Chevalier Theatre.

On Sundays the theatre was re-fashioned as a youth club, often with live music. Witnessing Devlin shake the house down in mid-1958, Dent saw an opportunity. Devlin and Warren, by now acting as Devlin’s de-facto manager, were equally enthused and Dent took the suggestion to his boss, Robert Kerridge. The cinema magnate was less enthusiastic but reluctantly agreed to a two-week North Island tour of Kerridge-Odeon theatres.

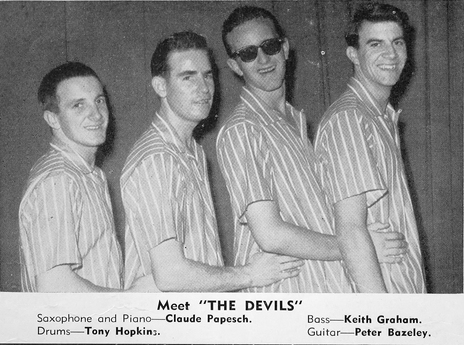

With Devlin’s regular backing band, the Bob Paris Combo, unavailable, Dent recruited a 16-year-old multi-instrumentalist and regular at the Point Chevalier Youth Club: Claude Papesch, who was particularly adept on piano and tenor saxophone.

The Devils - this was the band that toured New Zealand with Johnny Devlin in 1958-59.

Born blind, the son of a New Plymouth headmaster (also blind), Claude Papesch had shifted north in his early teens to continue schooling at Auckland’s New Zealand Foundation for the Blind. Despite his tender years, Papesch was appointed band leader, recruiting guitarist Peter Bazley, bassist Keith Graham (brother of future National Party MP Doug Graham), and drummer Tony Hopkins, all young but proficient musicians. The chosen band name was a sitter really: The Devils.

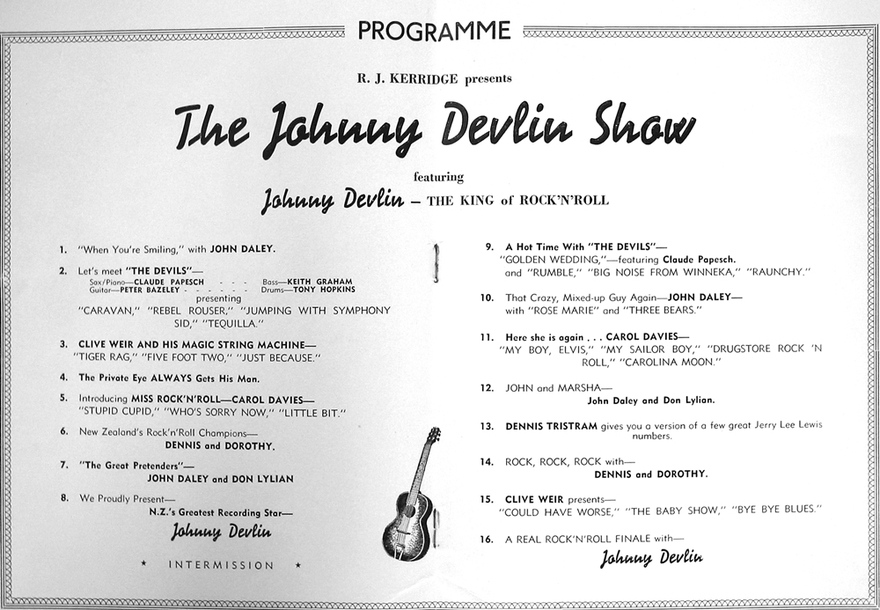

The tour was a co-promotion between Kerridge-Odeon and Phil Warren’s Prestige Promotions, and Warren secured a sponsor in Coca-Cola, which had only recently become available in New Zealand. The original tour line-up featured Devlin and band, 18-year-old songstress Carol Davies (“New Zealand’s Connie Francis”), and the rock’n’roll dance duo Dennis and Dorothy Tristram. (The latter were invited partly at Devlin’s instigation: the couple were old friends from Palmerston North and it was Dennis who had introduced Devlin to Dave Dunningham, an event which furthered his career.) John Daley was MC and the programme was completed with banjo player Clive Weir and comedian Don Lylian.

Devlin, band, Carol Davies and the dance team were constants, but there were changes to the line-up before tour’s end. Those to join the tour included magician/ventriloquist Jon Zealando and drag artist Noel McKay. Rock’n’roll aside, the variety show format still ruled.

The 1958/59 NZ tour programme

The Johnny Devlin Show, as it was officially billed, started at Wellington’s St James Theatre on Friday 21 November. Four of the six scheduled shows were pre-sold, partly due to Graham Dent’s manipulation of the Wellington press. He advised the newspapers that Devlin’s debut single, ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ had sold an astonishing 58,000 copies and Devlin was to receive a whopping £165 a week. Neither was true; at that stage ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ had sold a very respectable 20,000 copies and Devlin’s weekly fee was £75.

Throughout the tour, Devlin’s earnings were regularly reported, or mis-reported. The New Zealand media and, indeed, the public, shared a fascination with a performer, barely out of his teens, who could command such an income. (During the tour, New Zealand’s average weekly wage – for factory workers – was just under £15 for males, or £8 for females.)

The Wellington season was a huge success and, aided by often ecstatic newspaper reviews, the remaining shows around the North Island quickly sold out. The Evening Post reported, “The theatre shook, it bounced up and down, so did the audience, so did Devlin, so did his band, and the pianist rolled on the floor and the audience was in a frenzy.” Even before the remaining concerts in Masterton, Palmerston North, Napier, Gisborne and Tauranga, Dent added two more weeks to the schedule. The Johnny Devlin Show was a box office phenomenon.

Johnny Devlin and band, Napier, January 1959 - Hawke's Bay Photo News

The show was back in Wellington before Christmas and Warren had organised record store appearances to promote Devlin’s growing catalogue. In December alone, Prestige released no fewer than five Devlin singles for the Christmas market. During the tour, between November 1958 and May 1959, Prestige released eight singles, three EPs and a full-length album. Record sales were unprecedented.

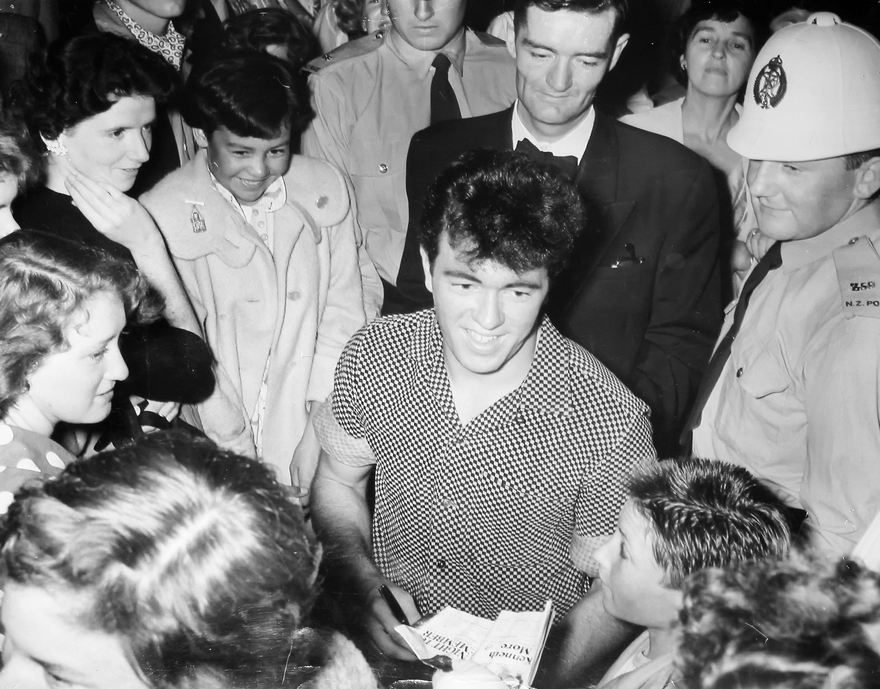

At a Lower Hutt record store appearance an over-enthusiastic crowd knocked over a glass display case in their excitement. The following day Devlin was spotted leaving the St James Theatre in Wellington, and was chased by a screaming throng into a building site, where he was manhandled and, it was reported, his shirt ripped off his back.

In truth, the shirt tearing, which became an almost-daily occurrence, was another of Dent’s media stunts. The loose stitching guaranteed the shirts all but fell apart with little groping. The New Zealand media gobbled it up. Johnny Devlin had become headline news.

Over Christmas the entourage took a two-week break while Devlin and band recorded a new batch of recordings for Prestige. In the new year the tour recommenced in Christchurch and although ticket sales were respectable in Christchurch, the remaining South Island dates were dismal.

Alarmed by this, Robert Kerridge ordered Dent to cancel the South Island tour and only reluctantly agreed to proceeding with the Christchurch dates. There were two reasons for the general lack of interest down south: a 17-year-old apprentice bricklayer named Max Merritt, and roller-skating.

Max Merritt was Christchurch’s rock’n’roll pioneer and with his band the Meteors was already well-established throughout the South Island. Merritt’s parents operated a Sunday youth club, The Teenage Club, more or less based around their son’s band, which was managed by Kerridge-Odeon’s top Christchurch employee, Trevor King.

King advised Dent and Robert Kerridge that Devlin’s Christchurch dates coincided with the national roller-skate championships at the King Edward Barracks, a spacious former military building in Hereford Street. Furthermore, King himself, ever the promoter, had organised a “Rock’n’Roll Jamboree” at the barracks on the following Monday.

Johnny Devlin signing the Kerridge-Odeon programme of his tour, December 1958.

King told me in 1981, “They had constructed a number of platforms and the like for the skaters and I wanted to utilise them before they were dismantled. At one end of the building we had Max and the Meteors and at the other end, on another platform, we had Martin Winiata’s band [Martin Winiata and his Moonmen], each playing 30-minute sets, no breaks. I must say I was totally surprised when Graham insisted that he wanted to proceed with Devlin’s show at the [Christchurch] St James on the same night and I urged against it.”

En route to Christchurch, Dent chanced upon an old friend in Wellington, Geoffrey Caine, who was press secretery for Sydenham MP and Minister of Social Welfare, Mabel Howard – never shy of a headline herself. The pair cooked up a plan to aid both parties.

Dent announced to the press that Miss Howard would attend Devlin’s Monday night concert and accompany him to the King Edward Barracks to meet Max Merritt. “King of the North Meets King of the South” was the imagined headline. A story in the following day’s edition of The Press (syndicated nationwide through the NZ Press Association), wrote it up: “The Minister Of Social Welfare, Miss Mabel Howard, visited the Johnny Devlin Show in Christchurch last night and was welcomed by Johnny from the stage with a ‘a very big terrific hello for a very wonderful woman’ … ‘I’m really enjoying the show. There’s nothing much wrong with rock’n’roll,’ said the minister at half time …”

Departing the theatre, Devlin and Miss Howard struggled through several hundred waiting fans where, no surprise, Devlin lost another shirt. Two policemen were knocked to the ground in the melee, their helmets crushed, before the pair were driven to the King Edward Barracks in a pink open-top Cadillac, hired by Dent. The Press reported 2,400 people inside the venue and 3,000 outside. Ticket sales for the remaining South Island dates sky-rocketed and a second Christchurch season arranged.

Cabinet Minister Mabel Howard meets Johnny Devlin, Christchurch, December 1958. Promoter Trevor King holds the microphone.

In the March 2nd edition of Joy magazine, Carol Davies said, “It was all good clean fun there [Christchurch]. In Greymouth and Westport especially, the numbers were almost as great but an element of roughness and hooliganism completely ruined our visit. We were dragged out of our taxis, pushed around, windows were broken – the show was completely spoiled. Fortunately, this reception is more the exception than the rule. In Dunedin and Bluff things got a bit out of hand, but overall, the South Island tour was great fun.”

Following another two-week break, a third and final leg of The Johnny Devlin Show continued around the North Island. Mostly reliant on public transport to get around, there were reports of small crowds gathering at railway stations along the way just to get a glimpse of the “Satin Satan” (another Dentism).

The stage antics themselves were straight out of the American rock’n’roll movies that were so prevalent at the time: Keith Graham standing on his bass, Bazely and Papesch playing on their backs, Devlin jumping atop the piano. Tony Hopkins often played drums standing up. Dent introduced other tricks like Papesch arriving on stage holding onto the fly line. Hopkins told me: “Claude would come flying in, holding onto the rope, sax in hand, and I would have to signal him to let go – above his spot on stage – with my crash cymbal. Whenever Claude pissed us off, which he did occasionally, I would deliberately hold back, leaving Claude swinging back and forth over the audience. One time, I deliberately send him sprawling into the orchestra pit. He wasn’t too happy about that.”

Papesch received no special treatment and his blindness was often a source of humour for the entourage. “Those bastards would put grass and flowers in my salad,” he told me many years later. Peter Bazley appointed himself as Papesch’s minder but wasn’t above some mischief himself. Out walking, he’d say, “There’s a step there, Claude,” when there was no step, leaving him hopelessly pawing the ground to great mirth. Papesch, who would familiarise himself with every room he entered, would get his revenge by taking out all the light bulbs or, on one occasion, hiding all the dressing room mirrors.

A town hall somewhere in New Zealand, 1958/59

For his part, Devlin didn’t indulge in shenanigans as much as the others. A staunch Catholic, to everyone’s amazement he attended church every Sunday. Another of Dent’s ideas, Devlin was teamed with Prime Minister Walter Nash and visiting American evangelist Billy Graham. The photograph opportunity for the press was headlined “The Three Leaders”.

The tour continued through to May 1959. Robert Kerridge himself ordered it come to an end, regardless of continuing profits margins. Besides, there was a growing dissatisfaction within the ranks. At an Auckland press conference Phil Warren handed Devlin a royalty cheque for £2,320/1s/6d, an astonishing amount for a New Zealand performer, but the last journalist had no sooner departed before Warren ripped up the cheque, just one more publicity stunt. It did, however, lead Devlin to query exactly how much he was due.

Within weeks of tour’s end, Phil Warren had secured Devlin and band, plus Carol Davies, slots on an Australasian package tour headlined by the Everly Brothers. Johnny Devlin has remained an Australian resident since. He retained The Devils moniker for his backing band over the coming years but the original line-up didn’t remain together long in Australia. Hopkins and Papesch soon switched to jazz, which was always more to their liking. Peter Bazley joined Australian rocker Lonnie Lee’s band the Leemen. Keith Graham returned to Auckland as an original member of the Embers.

Graham Dent’s hyperbole aside, there is little doubt that Johnny Devlin’s Kerridge-Odeon tour was a watershed period in New Zealand music. But at this distance in time it is difficult to ascertain exactly what was real and what was hyped. For instance, in 1981 Dent told me that an over-enthusiastic crowd in Greymouth was fire-hosed. Ten years later he confessed that it was he, not the authorities, who had used the fire hose, and as a prank rather than actually containing teenage exuberance. And the media was either gullible or culpable, complicit in much of the hype that was generated. Regardless, it would be safe to suggest that the hysteria and media attention generated by Johnny Devlin’s six-month tour will never be repeated.

--

In 2022 a short tape turned up of Johnny Devlin performing live in Christchurch on the 1958-1959 tour. An exciting cut from it is included towards the end of this programme about the audition acetates he recorded in Dannevirke in 1957, before he left Whanganui.