Founded in 1963, the Tauranga National Jazz Festival claims to be the world’s longest-running city-based jazz festival and, more than 60 years later, it is still going strong. While not the first New Zealand jazz festival, it is the most historically significant. It was the first such festival to present a regionally diverse range of New Zealand improvisers, allowing them to showcase their skills in front of a large audience. Instead of coming on stage as pick-up rhythm sections, guest artists or opening acts, New Zealand musicians took centre stage.

Miho's Jazz Orchestra performing for the Hurricane Party in Tauranga for the National Jazz Festival in 2022. - David Dunham

1963 was an interesting time for this first festival to occur. Swing bands were still popular, and there was an enthusiastic trad scene here. It was also when esteemed American albums of the late 1950s, such as Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out (both released in 1959), had filtered through our import restrictions and engaged new listeners. The “cool” West Coast jazz sound was also becoming popular, with its tight arrangements and broad audience appeal.

The cool style bridged the divide between the swing audiences and those who preferred modern jazz, influencing local arrangers such as Wayne Senior and Bernie Allen. As the festival found its feet, cool, trad, bebop and swing could all be heard, diverse styles co-existing, and the fans basked in the experience of having a variety of homegrown jazz on their doorstep. By the 1970s, an even greater diversity of styles emerged.

The founding members of the organising committee debated whether the festival should be kept under local control. Most of the committee were devotees of swing music, but the first programme promised a range of styles to broaden the appeal. The 1963 concert, however, offered none of what they termed “progressive jazz”.

Tauranga drummer Dave Hall, the festival visionary. - Tauranga City Libraries, Eph 14-016

The first Tauranga Jazz Festival was held in January 1963, during Auckland’s anniversary weekend (it later moved to Easter weekend). The idea appears to have been the brainchild of Tauranga-based drummer Dave Hall, who discussed it with local musicians, family members and enthusiasts. As well as Hall, Dave Proud, Ken Hayman, Del Peterson, Stan Day and Ken White made significant contributions. While Tauranga was a provincial town and not the obvious place for such an event, it possessed an enthusiastic and growing music scene.

In 1961 flute player Stan Farnsworth – a recent immigrant from the UK, who had played with the Ted Heath band – formed the 17-piece Tauranga Swing Musicians Show Band. The following year, drummer Dave Hall proclaimed himself band leader, and after seeing the 1959 film Jazz On A Summer’s Day [filmed at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival], began organising a similar festival for Tauranga.

Jazz musicians on a VW ute, Tauranga National Jazz Festival, 1969 - Bay of Plenty Photo News, 3 May 1969

News that the event was about to be held appeared in the Auckland Star in December 1962. The concert was billed as Jazz on a Summer’s Night and a brief article stated that some “top musicians” from throughout New Zealand would appear. Three names were mentioned: Nolan Rafferty, Jock Nisbet and Pem Sheppard. People who attended recall that nine bands appeared. According to Dennis Huggard’s invaluable Tauranga Jazz Festival performance log, The Alex McLean Tapes, among them were the Jack Randell Sextet (Jack Randell on piano, Ione Sheppard trumpet, her husband Pem Sheppard saxophone, Neil Dunningham trombone, John Rogan drums, and Bert Penny on bass), and the Ray Stench Octet (whose personnel isn’t listed).

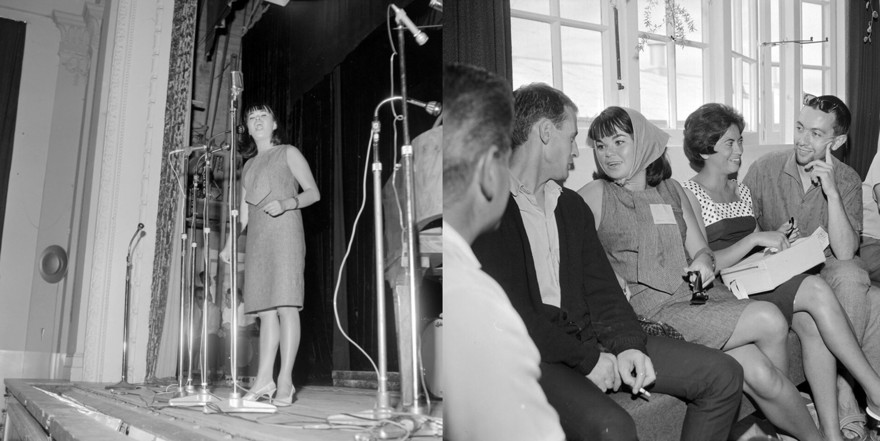

Marlene Tong performing at the 1965 festival, and relaxing afterwards; bassist Lester Still at far right. - Tauranga City Libraries, gca-8479, gca-8406

The open-air venue was pleasant, but the Tauranga Soundshell could be acoustically challenging; later, different venues were tried. It is doubtful that the bands had performed in such a large venue before, but they were delighted to be there and made it work. More than a thousand people attended the inaugural concert, and the success prompted the organisers to plan a bigger event for the following year. It was reported in a local paper that the 1964 festival could begin with a head start, as a £30 profit had been made in 1963 (equivalent to $1600 in 2025).

Flyer for the 6th New Zealand National Jazz Festival, Tauranga 1968. - Tauranga City Libraries, Eph 14-016

By 1964, there was more detailed reportage. A delightful article by Neil Colquhoun appeared in the NZ Listener immediately afterwards. This was an inflexion point: here was a New Zealand musician/folk scholar writing about a local jazz event and capturing the excitement. Absent was the cultural cringe that had often characterised musical reportage to date; it had none of the endless comparisons with offshore artists. This was an insider telling the story, beginning with an account of the soundcheck and the sudden panic experienced by the musicians as the audience filed in. It captured the vibe nicely. This was engaging jazz journalism, not an account that a stuffy armchair critic might have written.

“It was a hot summer’s day, two-thirty, Sunday afternoon,” Colquhoun wrote. “The empty but brightly coloured seats stood, row by row, before us in the glaring sun. I sat at the flat-top piano, making chords as they tested the sound system … Doug Hitchcock, the programme man, paced about the stage. The first scheduled combo hadn’t turned up yet … Mike Foster, the technician, waved a bass player to step closer to the microphone. Suddenly, my eye caught a trickle of people making for the seats. They’d opened the gates! Backstage, the missing combo materialised … [there was] no time to go home and change, we’d be on in a second. And so it was, in shorts, shoeless, and unshaven, we played jazz on a hot summer’s afternoon at the second National Jazz Festival at Tauranga.”

Front cover of the programme for the 8th Tauranga National Jazz Festival, 1970. - Tauranga City Libraries, Eph 113630

His descriptions of the rehearsals were equally evocative. He observed that the Ernie Rouse Allstars, a Hawke’s Bay band – “we play traditional jazz, not trad, not dixie” – could easily have been a shearing gang. “The only polished-looking thing about them was their horns, which shone like burnished gold … They were a good band, they brought the house down when they appeared.” He describes watching Stan Farnsworth rehearsing the Tauranga Swing Band as a delight. Farnsworth “knew the value of, and consequently demanded, a clean attack, controlled tone, and above all, a swinging rhythm. All of the band were good readers and the band’s sound was magnificent.”

The warm-up act was a trio led by a 16-year-old Auckland schoolboy pianist, who astounded the audience with his piano technique. He was reported as having a “wonderful feeling for jazz … His rendition of Red Garland’s arrangement of ‘Billy Boy’ swung with full-chord fire, “while the solos were reportedly his own.”

16-year-old Alan Broadbent performing at the third festival, January 1964. - Tauranga City Libraries, gca-6222

The young performer was Alan Broadbent. A few years later he moved to the United States and became a Grammy-winning artist. Broadbent studied with Lennie Tristano, played and arranged with Woody Herman’s Herd, Bud Shank, Chet Baker, arranged music for award-winning albums (among them Barbra Streisand, Natalie Cole, Paul McCartney) and played, wrote and arranged for Charlie Haden’s Quartet West, one of the best-loved jazz bands in the US. Broadbent is arguably our greatest jazz export.

Performing at the Tauranga Jazz Festival gave musicians the confidence to try their luck in the wider jazz world. Broadbent’s contribution, young as he was, is significant. Modern jazz had arrived at the festival.

Richard Hardie provides a detailed analysis of this and subsequent festivals in the excellent book, Jazz Aotearoa. He examines the events in detail, providing a deeper context. Jazz was becoming bolder and edgier, as its mainstream pop appeal faded and the festival organisers recognised this. A piece in the Bay of Plenty Times, reflecting on the 1964 concert, summed this up. “The festival achieved one of its main objectives, it allowed the musicians to play the music they like rather than that which commercial engagements dictate.” The more sophisticated the bands became, the broader the tastes of the listening audience grew.

Alan Broadbent, centre, with (L-R) Graham Price, Bob Douglass, and Bobbie Sutherland, January 1965. - Tauranga City Libraries, gca-8475

Performing at the second festival were the Mike Walker Trio, John Wilcox Trio, Windy City Six, The Swingers with Barbie Colquhoun, Tauranga Swing Musicians Band, Bob Kevin Trio, Bruce Morley Sextet, and the Oli Newbegin Sextet. In 1965, the 17-year-old Alan Broadbent appeared again as a member of the Merv Thomas Octet; later the Dave Donovan Quintet appeared featuring the soon-to-be-famous sax player Jimmy Sloggett, followed by Wayne Senior’s The Voices, a vocal quartet.

In the years that followed, bebop featured frequently. By 1967 the Tauranga Swing Musicians had included the Dizzy Gillespie bebop classic ‘Salt Peanuts’ in their repertoire. By this time, the festival reflected a balance of older and current jazz.

By 1968, the festival had expanded from one concert to three, and it was reported that people were turned away as they quickly reached capacity. The success was due to the selfless efforts of a devoted team of volunteers. The enterprise was financed on the smell of an oily rag, but as it grew, it became obvious that a more structured organisation was required, which resulted in people being hired to manage the event. It was not all plain sailing in those early years either.

With increasingly discriminating audiences attending, and musicians’ tastes broadening, it was inevitable that modal jazz and the “new thing” (free jazz) would arrive. What was controversial in the US was bound to be so in New Zealand, so it is interesting to tease this out. Drummer and bandleader Frank Gibson Jr, among others – influenced by the likes of John Coltrane – moved the dial forward in bringing modal music to the stage, while saxophonist Jim Langabeer introduced free jazz.

To quote Richard Hardie in Jazz Aotearoa, “Based on the reception of his performance that year (1968), one wonders if he [Langabeer] was prepared for just how far ahead of everyone else his trio was in terms of free improvisation.” Langabeer had come up from Christchurch, with bassist Paul Dyne and drummer Ted Meager. He had a reputation for challenging those he perceived to be too conservative. The festival organisers accepted this new and challenging music, however, many professed that they hated it; what Langabeer offered was baked into the festival’s kaupapa: musicians playing what they wanted.

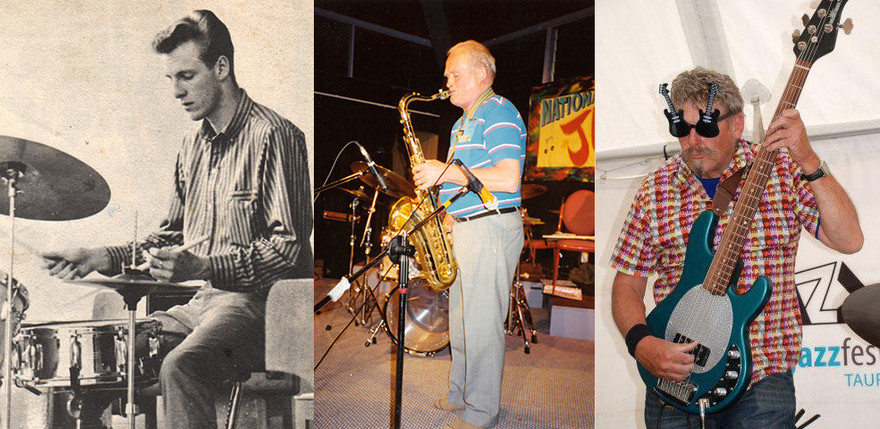

Frank Gibson Jr at the 1966 festival; Stu Buchanan, 1990s (photo by Dennis Huggard), Murray Loveridge with Blues Buffet in 2010.

By then, the festival was providing more than just entertainment, it was fostering the development of experimental music, something often impossible in the other centres. It also offered workshops and invited high school jazz bands to perform. The high school jazz band competition, under-subscribed initially, soon became a key feature of the festival. In 1969, hard bop was on offer, with the Jazz Adventurers playing ‘Sidewinder’. The year before, Acker Bilk had appeared: diversity indeed.

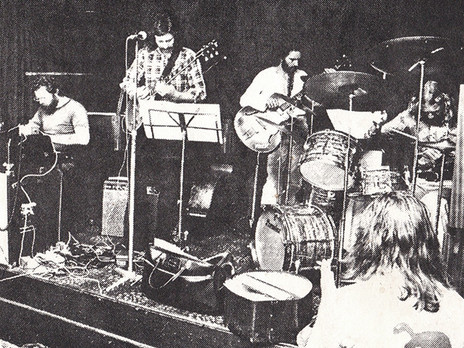

Dr Tree (L-R): Murray McNabb, Martin Winch, Bob Jackson, and Frank Gibson Jr

By the 1970s, modernism dominated, with musicians well known to current jazz audiences, in particular Frank Gibson Jr, Mike Nock and Rodger Fox. In 1970, Ray Harris reported in his Listener column, “This year may prove to be a milestone of jazz down under … jazz is a happening thing in New Zealand and the Easter festival augurs well for all those who plan to attend.” Returning from the US to perform was Mike Nock, one of New Zealand’s most significant musicians. By then, the festival had moved to the Tauranga racecourse.

The early 1970s also saw jazz/rock fusion hit the festival stage. Jazz, by its very nature, never stands still. In 1974, the NZ Herald headed its Tauranga Jazz Festival review, “Is the gap between rock and jazz narrowing?” Again, drummer Frank Gibson Jr moved the dial with Dr Tree, which also featured trumpeter Kim Paterson, pianist Murray McNabb, guitarist Martin Winch, Bob Jackson on bass, and John Banks on percussion. Also appearing, but not mentioned by Huggard, was the Neophonic Orchestra, which had recently been under the baton of US composer and bandleader Russ Garcia.

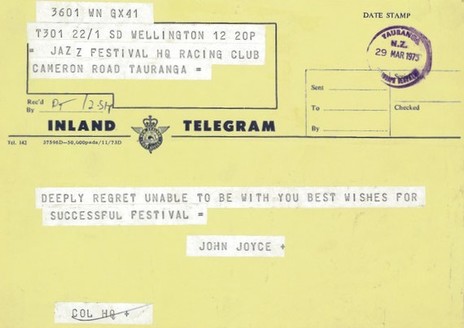

John Joyce regrets: Radio New Zealand's jazz stalwart sends his apologies, 1975. - Tauranga City Libraries, Eph 14-017

While the Tauranga Jazz Festival was very much a festival for Aotearoa musicians, the first decades featured some international acts. The Novi Singers, from Poland, appeared in 1969. It is fascinating that a septet from Cold War Poland is listed as the first international act to appear at the festival. They had been booked by an agent in Sydney with the extraordinary alto saxophonist Zbigniew Namysłowski (a fiery saxophonist who appeared with Krysztof Komeda on Astigmatic).

Judy Bailey, whose accompanying note in the festival scrapbook reads: “Having a wonderful time! May the National Jazz Festival of Tauranga continue for ever and ever. Cheers for now.” - Tauranga City Libraries, Eph 14-017, CC 3.0

In 1972 the festival producers took a huge financial risk when they booked Stan Getz and Gary Burton, each with their backing musicians. Getz was, at the time, arguably the most famous jazz saxophonist in the world, and Burton had just won the Downbeat jazz poll. I was initially puzzled why this important act was not listed in Huggard’s records, but I suspect it was because it was held in the town hall (as was the Acker Bilk show).

Judy Bailey, a New Zealand-born pianist who had moved to Australia, was also a headline act that year. The Herald reported that the Tauranga Jazz festival could now be compared to any of the world’s jazz festivals.

1976 began on an ominous note, with a Herald headline declaring that the Jazz Society was on the verge of bankruptcy. The committee appealed to Tauranga Jazz Festival supporters and the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council for assistance. Luckily, $750 – the equivalent to $8200 in 2025 – was raised from supporters and local organisations.

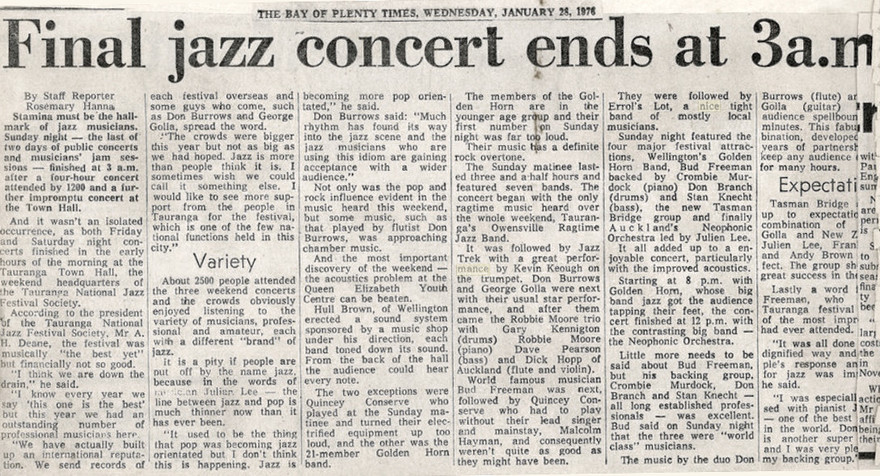

The best year yet, but financially not so good: Bay of Plenty Times, 28 January 1976. Tauranga City Libraries, Eph-14-018

Despite the unsettling events, the American saxophonist and clarinet player Bud Freeman took to the stage. He was accompanied by local musicians Crombie Murdoch on piano, Stan Necht on bass, and drummer Don Branch. Freeman was a legendary figure in US jazz. Another international musician, Australian Don Burrows, also appeared that year. His band was a trans-Tasman affair, appropriately called Tasman Bridge. Afterwards, Burrows heaped praise on blind New Zealand pianist Julian Lee, telling reporters that he was one of the finest pianists in the jazz world.

The next headline act was the Ink Spots, a popular American vocal group who performed the following year. Local drummer Don Branch is listed on the programme as “an honorary Ink Spot”.

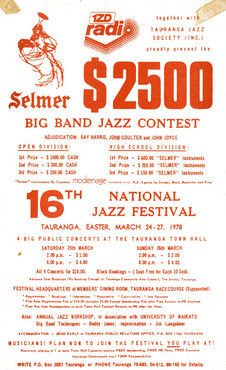

In 1978, $2500 was the prize in the Big Band Jazz Contest. Judges were Ray Harris, John Coulter, and John Joyce. Tauranga City Libraries, Eph 14-017

The following year, 1977, saw a programming clash between the Tauranga festival and the Auckland jazz festival, as Mavis Rivers was booked to appear in Auckland over the Easter Weekend. An article in the Herald stated that the fault lay with Tauranga, as the committee had earlier cast doubt whether the festival could proceed due to cash difficulties. Also, there were weather problems, so the main concert had to move to the Queen Elizabeth Youth Centre, a venue that had been rejected previously due to acoustic issues. To make matters worse, there was a power cut, so audience numbers were down. It was ultimately decided to scale the Tauranga festival back for that year and hold workshops in Tauranga instead.

A few years later, a situation beyond the organisers’ control nearly resulted in a cancellation. In 1979-80, the international fuel crisis hit. The Herald reported that the event might not be able to proceed due to weekend fuel restrictions. By Easter weekend, however, the rules had been eased, and the anxious committee hastily permitted late registrations. As a concession to the fuel shortage, the festival only held two concerts, on the same day, and composer educator Colin Hemmingsen and percussionist Bud Jones ran workshops organised by the Waikato University. The school bands competition went ahead, though, and afterwards the festival committee told reporters that the restrictions had done them a favour. Everything had been held at the racecourse, meaning people mingled more, which was conducive to a friendlier atmosphere.

Rodger Fox Band (Youth Band, Northcote) with Mary Yandall on vocals, 25th National Jazz Festival, 1987. - Tauranga City Libraries, photo 12-537

On the 1986 programme were the Rodger Fox Big Band, with Mary Yandall on vocals; The Paul Norman Sextet; bassist Kevin Haines with Second Generation, featuring his sons Nathan and Joel Haines. Also, Ricky Powell; Los Gatos led by Roger Ward; and Dr Jazz and Friends. Bernie Allen led a 20-piece jazz orchestra, accompanied by a seven-piece vocal section. Listed were the high school bands: Tauranga Boys College Band, Logan Park High School Band and Northcote College Band.

For the 25th anniversary of the festival in 1987 a special effort was made. Phil Broadhurst’s Sustenance was described as the headline act, followed by Jim Langabeer, George Chisholm, Frank Gibson Jr, and Rodger Fox. Air New Zealand flew in George Golla from Australia, and the Youth Competitions picked up its first sponsor (Northcote College won the best big band trophy). Despite the festival’s benefit to the city, the Tauranga City Council refused to let the organisers put banners up. The one sour note in a successful celebration.

Kenny Pearson with the Rodger Fox Big Band; Jan Preston, 2001; Nathan Haines, 2004. - Tauranga City Libraries, photos 01-298, 12-487, 12-513 Festival

By this time, the festival had grown significantly, and the aging committee admitted two younger members, Derek Jacombs and Damian Forlong. A suggestion made by these new committee members altered the format by convincing local cafes and bars to host bands, resulting in the musicians getting paid. Because of this, the downtown street festivals emerged, and bands playing along the strip remain a key focus of the festival. The Tauranga City Council, although late to the party, was by then fully on board. After all, the festival had filled the city’s coffers from day one.

As in the early years, the recent festivals reflect the changing times. Blues, soul, and hybrid forms of improvised music are more prominent. With the advent of streaming platforms, people can access a wide variety of music, and younger audiences are not so wedded to the strictures of form. Indie groups now feature alongside mainstream improvising musicians, the former often learning their craft in a jazz school. A good example is Finn Scholes’ Carnivorous Plant Society, an ensemble that combines free jazz, world music, spoken word and indie pop, and utilises a light show. Scholes plays at festivals, popular music or rock venues and jazz clubs and has been an audience favourite at Tauranga in recent years. It was no different in 1974, when the festival featured The Quincy Conserve.

When did jazz ever stand still? From its inception to the present time, the festival has run on the sweat of its volunteers and the commitment of its musicians. All credit to them.

The Torn Sack appearance at the 7th National Jazz Festival in Tauranga in 1969, Bill Fairs at far left. - Bill Fairs collection

I first attended the Tauranga National Jazz Festival in the late 1960s. After reading Kerouac’s On The Road, I wanted a piece of the jazz life, to immerse myself in live jazz and experience the wild energies. As a school boy, I loitered outside jazz clubs like the Embers, too young and poor to enter, straining to hear any music that escaped, believing that jazz happened in smoke-filled basements where people wore dark glasses and passed joints around.

The Tauranga festival was not that, but what I experienced delighted me. Watching and listening to the “cats” onstage sent a shiver down my spine. After that, I was determined to connect with jazz musicians; only alchemists could conjure up that brand of magic. It was years before I attended again as I had been travelling and living overseas, but I never lost that sense of wonder.

Dave Maybee performing with Torch Songs at the Tauranga Jazz Festival. From left: Neil Reynolds, Grant Mason, Wayne Melville, Natalia Lunson, Carol Story, Dave Maybee and Liam Ryan. - Dave Maybee Collection

The last time I attended was as a reviewer. In 2015, Dog (Roger Manins, saxophone; Kevin Field, piano; Oli Holland, bass; and Ron Samsom, drums) won the Jazz Album of the Year Award (the jazz Tui) and it was presented by the Tauranga festival organiser Liam Ryan. The strip was alive with diverse musical genres, Rodger Fox hustling as only Rodger could, drumming up support for a jazz grant he hoped to extract from the government, and the musicians and audience happily soaking up the vibe. After Dog played, the French/Australian pianist Chris Cody sat in and played ‘I Love Paris’. I can still sense the joy, as I replay it note for note in my head. On reflection, my adolescent dreams came true. These days I regularly “hang” with the “cats”, many of whom are my closest friends.

The jazz Tui award soon returned to the Wellington International Jazz Festival. It is sometimes suggested that rival festivals like the Wellington International Jazz Festival or the Waiheke Jazz Festival – also held over Easter weekend – have diminished the importance of the Tauranga National Jazz Festival, but that is not the case. Every city deserves its jazz festival; each has its vibe, and they will endure if the support is there.

Link: Tauranga National Jazz Festival

--

John Fenton is an Auckland jazz writer, videographer, photographer, poet and writer. His blog jazzlocal32.com has been rated as being among the world’s top 50 Jazz Blogs.

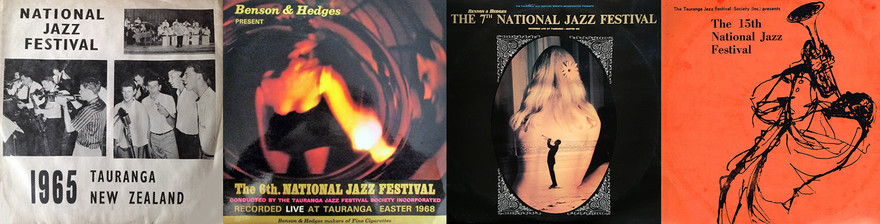

Tauranga National Jazz Festival LPs.

For the festival’s first 29 years, Alex MacLean of Raetihi took his mobile recording gear to Tauranga to tape many of the performances. Until at least 1987, highlights of these were released on LP by the Tauranga Jazz Society. A list of MacLean’s recordings can be read in the 2003 edition of Dennis Huggard’s booklet The Alex MacLean Jazz Festival Tapes, online at the National Library website.

The load-out: Alec MacLean and daughter Vida at the 1967 festival. - Tauranga City Libraries, gcc-15607

--

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Norman Meehan for his assistance with archival material, the Dennis Huggard archives, Alex MacLean archives, The Right Note: an An Insight Into Tauranga’s Historic Music Scene by Graham Clark (Clark Design, 2015), “Jazz on a Summer’s Night: Hearing Voices at the Tauranga Jazz Festival,” in Jazz Aotearoa: Notes towards a New Zealand History edited by Richard Hardie and Allan Thomas (Steele Roberts, 2009), The Alexander Turnbull Library, NZ Listener (Neil Colquhoun), NZ Herald, Auckland Star, Bay of Plenty Times and numerous online sources, Jason Langworthy for proofing/editing suggestions, Chris Bourke and Tauranga Library for photos; lastly, the musicians who supplied information. The source material contained a few conflicting dates; I have exercised my judgement where that has occurred. As many as 300 musicians could play at a festival, so I have only selected a sample of the many musicians who appeared. The images here are the tip of the iceberg of what’s available at the Tauranga Library website; the ephemera is from the Margaret Petch festival scrapbooks held by the library, and librarian Harley Couper compiled a chronological history of the festival’s first 50 years. There are countless clips from the Tauranga National Jazz Festival at YouTube.

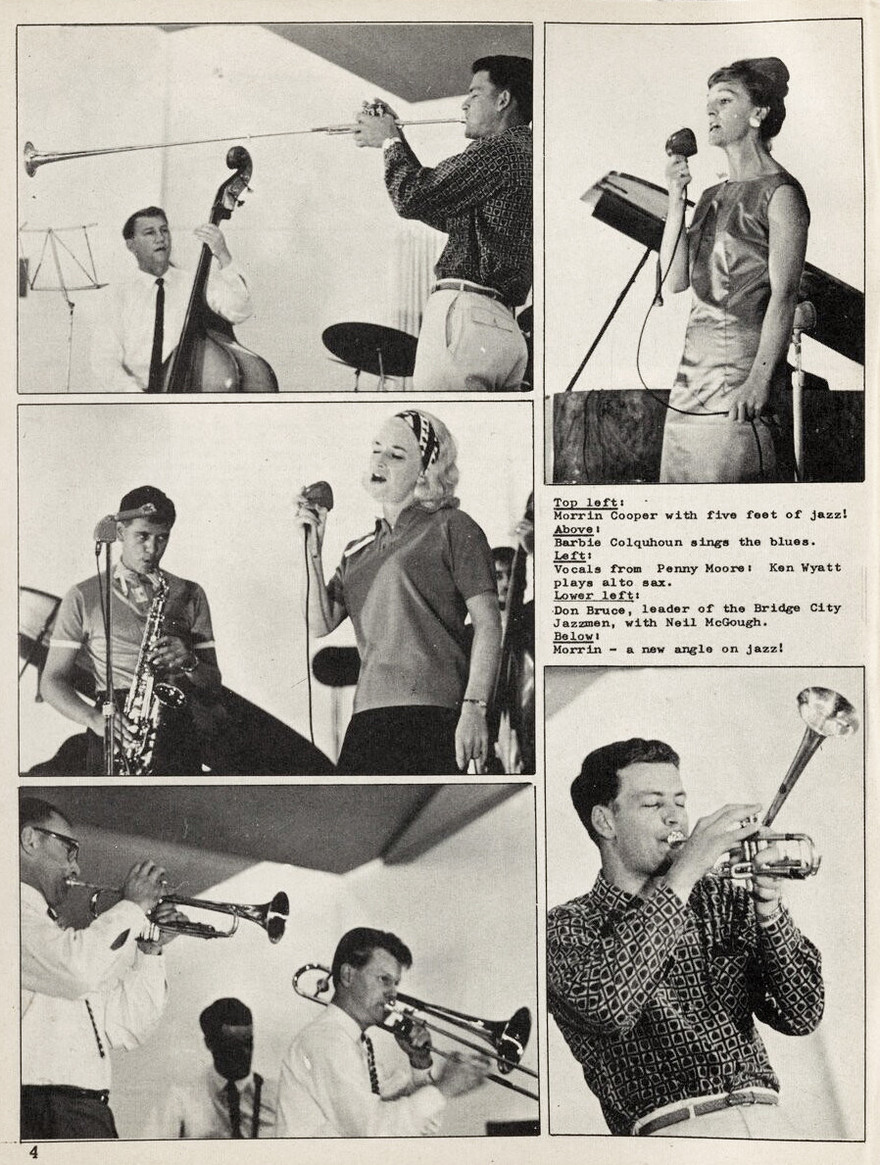

Artists from the second festival, 25-26 January 1964, from the Bay of Plenty Photo News. - Tauranga City Libraries