In the mid 1960s strange new sounds began spreading across New Zealand from those hotbeds of liberal thought and wild behaviour – university towns. Folk clubs were springing up and John Mayall-inspired blues revivalists were getting their moan on, while in the clubs followers of Merseybeat were blending it all into pop.

At the heart of New Zealand’s wildest off-campus pubs and parties were scruffier bands of eccentric folk aficionados, who had rejected the British blues invasion’s amped-up vibe, opting instead for the raucous party-blues of the foot-stompin’ jug band sound.

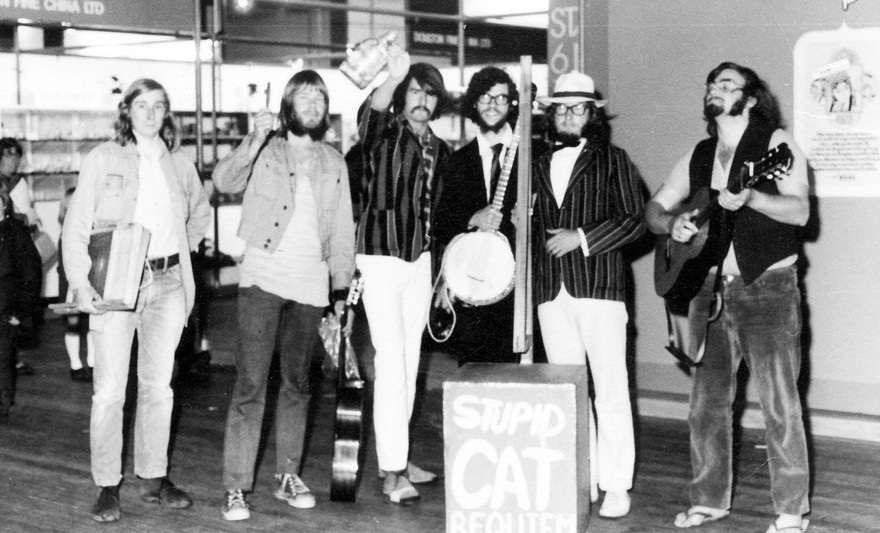

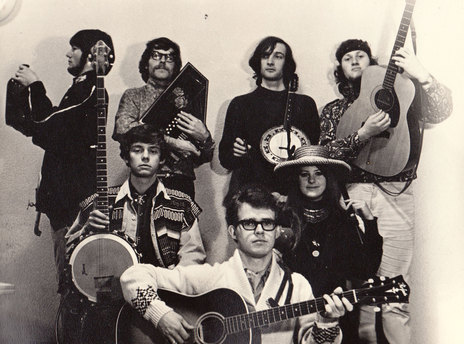

The Regurgitated George Wilder Rehabilitation Society Bush Band (Max Winnie, Warwick Brock, Bob Silbery, Arthur Toms etc), National Banjo Pickers Convention, 1969. - Trevor Ruffell

Jug bands originated along the Mississippi River from Memphis to St. Louis in the 1920s and 30s. Recordings of them – originally released on labels like Okeh, Victor, and Champion-Gennet – found a new lease of life alongside more popular reissues of urban and country blues such as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Lead Belly, and Robert Johnson. In jug music, keen listeners found a black dance-band sound that was neither orchestral or conventionally arranged. Hard-working sharecroppers in the pre-Depression South needed to party, and bands such as Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers and The Memphis Jug Band rose to the occasion.

They made and played with whatever was at hand: drums were supplanted with washboards, spoons, and found-object percussion racks (known as traps), blown jugs and tea chest basses stood in for bass fiddles, and combinations of banjos, guitars, mandolins, violins and spoons were also used. Skilled players jumped right in alongside enthusiastic amateurs, and the resulting lively mix influenced playing styles across the US.

Walk Right In

The pop-cultural peaks and valleys of jug jand music on the world stage can be roughly charted in the ups and downs of one song. The original recording of ‘Walk Right In’ by Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers (written by Cannon and Hosea Woods) was released in 1929. A new version, by the Rooftop Singers, charted internationally in 1963 and reached the No.1 spot in the US. Their bright, up-tempo take did a lot to popularise the 12-string guitar. Cannon, aged 80, responded to the renewed interest and released an album on Stax Records later that year.

Jug bands were prevalent in hippie America too. Like their contemporaries The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, The Lovin’ Spoonful started out as a jug band who went electric and became one of the most popular US bands of the mid-60s. Other bands with early jug incarnations include The Grateful Dead and Creedence Clearwater Revival.

Jug bands ran a spectrum from country blues folkiness to medicine show-style entertainers, and the starting point for many of the New Zealand groups was the Jim Kweskin Band from the US. Neil Worboys recalls: “My older brother brought a Jim Kweskin record home from university when I was still at school. He helped form the 10% Supermarket Discount band up in Napier in 68 or 69. When I was at secondary school we could go along and watch them on Sunday night at the Chez Paree, and that blew my mind. They were very good.”

Stupid Cat Requiem (L-R): John Kaiser, Neil Worboys, Bob Stephenson, Al Hall, Pete Green, Paul Brown.

Worboys and his friends responded by forming the Stupid Cat Requiem and, later, Bulldogs Allstar Goodtime Band – Aotearoa’s most commercially successful jug band. They employed dress-up box costumes and comic antics to great effect, showcasing Worboys’ great voice and some very catchy chart-topping tunes by John Donoghue (whose ‘Miss September’ hit No.2), Kevin Findlater, Worboys, and their manager, Dave Luther. Their theatrics and early troubadour-style expeditions around the North Island echoed contemporary counterparts BLERTA, with whom they shared a stage on occasion.

We’re not like them

The 1960s folk and blues boom was closely tied to the protest movement, and if there was ground more fertile than a university town for jug music to take root, it would be a university town that boasted a port.

“Instead of getting shipped to Vietnam, sailors could opt for two tours of duty at McMurdo base in Antarctica, and Christchurch was their jumping-off point,” says artist and musician Chris Grosz. “A lot of those guys jammed with our bands in bars and clubs, and some of them had records that were very good. There’d be black musicians joining in with us at parties, a lot of crossover between jug, skiffle, jazz and rock ‘n’ roll going on. They’d say ‘Why the hell are you interested in this sort of music? White people in the States don’t give a damn.’ And we’d reply, well, we’re not like them. We’re New Zealanders and we have a different take on things.”

The Band of Hope Jug Band, 1968. From left: Bill Hammond, Gordon Collier, Dobbin (Robin Elliot), Dennis Heartfield, Warwick Brock, and Chris Grosz. - Chris Grosz Collection

Grosz and Bill Hammond (who became one of New Zealand’s most distinctive and well-known painters) started playing music together early on. “I met Bill when I was 12. He was very interested in jazz, and took up playing drums in the style of Gene Krupa and Joe Morello. We’d listen to Lightnin’ Hopkins and his drummer Spider Kilpatrick – everything about us was rhythm driven. He taught me to play congas and we’d jam after school.”

Hammond, Grosz, and friends would play at the Folk Centre in Christchurch, which was run by Phil Garland who would soon be playing with them in the Band Of Hope.

Grosz found himself in a jug band with local boy Warwick Brock (like Grosz, an artist/designer) and Australian folk musician Frank Povah. “Frank had been in the earliest jug bands over there, The Battersea Heroes with Terry Darmody, and the Jellybean Jug Band which later became Captain Matchbox.” They formed the Ned Kelly Memorial Jug Stompers which featured Ron Davis, Frank Povah, Warwick Brock and Chris Grosz.

Band Of Hope

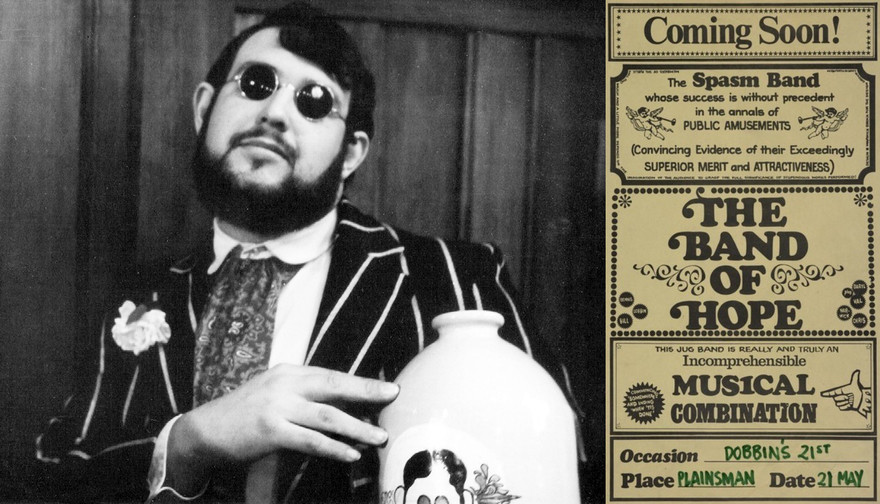

Band Of Hope (employing the droll humour common to many jug-band monikers, they were named after the Victorian era temperance movement) released two singles on Hoghton Hughes’ Sailor-Boy label and in 1968 recorded an album for the Kiwi label at the Folk Centre. Demonstrating the jug bands’ tendency to do a fair bit of instrument-swapping, the album features Warwick Brock on vocals, guitar, banjo, and kazoo (he also designed the cover); Gordon Collier on guitar, banjo, vocals; Phil Garland on jug, Chris Grosz on kazoo, vocals, harmonica; Tim Hazeldine on piano, Val Murphy on vocals, and Bill Hammond on washboard, tambourine, percussion, and spoons. They’d play at the Crossroads, the Plainsman, and folk nights on Sunday at the Stage Door.

Phil Garland while in the Band of Hope Jug Band, 1967; the band celebrates the 21st birthday of bassist Robin "Dobbin" Elliot, design by Warwick Brock, 1968. Phil Garland Collection; Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, Eph-C-MUSIC-Garland-1968-02

“Bill Gruar, the editor of one of the university magazines, managed to get us onto the Christchurch Jazz Society-sponsored concerts. Jug bands were frowned upon by the jazzers, but Bill argued that it’s the skeleton of jazz, the most primitive version of it. So why shouldn’t it be included? Whenever we played in small country towns, people would come out of the woodwork and it all became quite popular for a few years there.”‘

Band Of Hope toured the North Island, playing the Wellington Folk Festival then on up to Auckland to play the Wynyard Tavern, The Poles Apart, and The University of Auckland. I mention Al Park’s tale of seeing a wild and woolly Band Of Hope at The Balladeer in Wellington as an underage teen, sneaking in with his new girlfriend and being blown away.

Grosz: “I think that was the weekend that I ended up lying on the road after a party. It was appendicitis, I was rushed off to hospital. All part of the fun. I remember in Wellington we got together with the early Windy City Strugglers and had a big jug band jam which was fantastic.”

Like the Strugglers with their evolving ties to Mammal, Band Of Hope also developed an electric counterpart called The Plastic Mice. Grosz eventually got a bit fed up with Christchurch and split for Auckland, where he took up with The Mad Dog Jug and Jook Band.

Mad Dogs and Strugglers

“There was a sort of blues mania for about two years or so,” says Mad Dog guitarist Robbie Lavën. “There were a few but not many electric blues bands and a lot of the fundamentalist, extremely opinionated and protective fervour common to new converts of all kinds. The idea of ‘purist’ fitted into that even though it was silly at the time and even more silly in retrospect. Obviously, none of us were in St Louis or Memphis at the time of the great jug bands, and the cultural divide between black country blues and mostly white New Zealand university kids was and still is immense.”

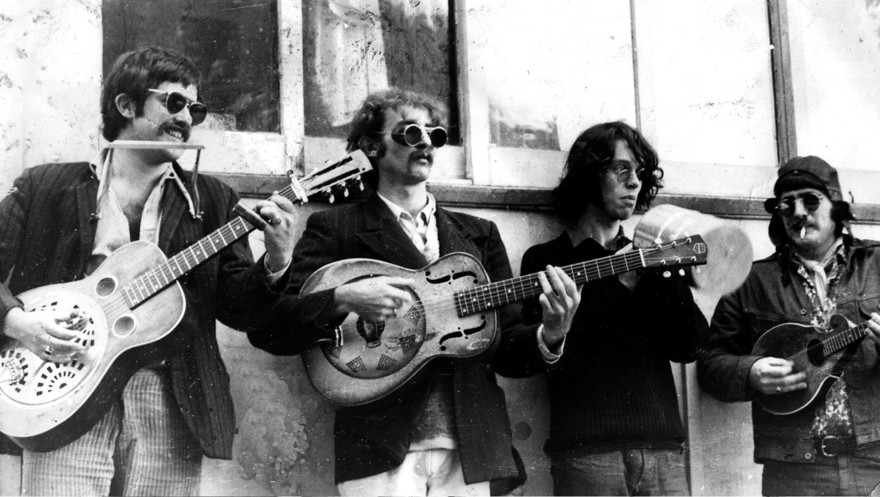

Oratia Blues Festival, Moller's Farm,1968. From left to right: Pete Kershaw, Robbie Lavën, Andrew Delahunty, Tom Crannitch, Paul "Cat" Tucker. - Susy Pointon

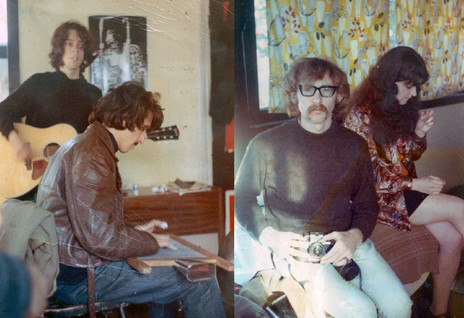

The band was formed after they saw the Jim Kweskin Jug Band in 1966 on Let’s Sing Out, a series of live hootenanny concerts filmed at various US universities. The line-up was Tom Crannitch on guitar and vocals, Paul “Cat” Tucker on washboard, kazoo, and vocals, and Pete Kershaw on tea-chest bass, harmonica, and slide guitar. Pete knew guitarist Henry Jackson from their electric blues band Killing Floor, but after a short time Jackson suggested Robbie Lavën as his replacement.

Mad Dog jam, 1967: Andrew Delahunty, Tom Crannitch; Pete Kershaw, Susy Pointon. - Christine Lavën

Crannitch, Tucker, Kershaw and Lavën remained the core of the band for about three years. Whistler left and was replaced by Pete Clements and then by Chris Grosz. Andrew Delahunty (later of The Windy City Strugglers) joined as harmonica player and various musicians sat in from time to time, including Jenny Parkinson, John Bergersen, folk singer/guitarist and chromatic harmonica player John Sutherland, folk singer/guitarist Chris Thompson and banjo player John Caldwell.

In photos, both the Mad Dog Jug and Jook Band and the Band Of Hope exude that mid/late 60s rebel-cool of counter-culture characters from the slightly dangerous side of weird, like an old time-y Velvet Underground – a million miles away from the novelty act end of the jug genre. You can read more about this cohort in Nick Bollinger’s excellent story on the Auckland blues boom.

Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band, Mangawa Rd, 1969. From left: Chris Grosz, Robbie Lavën, Andrew Delahunty, Tom Crannitch. - Photo by Susy Pointon

“The first jug player in News Zealand was Peter Doherty, who wore big white sheepskin boots and played a jug with beer in it while shuffling around the stage, says Lavën.” “The band took the ‘Mad Dog’ part of their name from him. The other bit came from an imported LP The Jug, Jook and Washboard Bands on the Blues Classics label featuring Washboard Sam on the front cover. The name caused some confusion. The Palmerston North Folk Club advertised the band as ‘Beware the Wild Dogs’.

“Audiences got off on the rebel thing and the novel washboard and tea-chest bass, the funny kazoos and the jug, but what really got them was our energy and musical flamboyancy and great grooves and irreverent humour. So we interpreted and kicked it in the guts and had a great time and loved the music without being earnest.”

The Mad Dog Jug and Jook Band never went into a recording studio, but feature on the 1968 Kiwi label highlights LP of the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. Kiwi Records released three live albums from these festivals.

The Windy City Strugglers come up in any conversation about the folk music boom in New Zealand, the general consensus being that they were ahead of the pack in many ways. In Australian expat Bill Lake they had a great musician who had amassed a collection of recordings and musical insights that leapfrogged them ahead of the growing pack, and together with the fabulous voice and stage presence of Rick Bryant and a line-up rounded out by Mike Rashbrooke, his brother Geoff, and Julie Needham on violin, they embraced the blues and folk territory mapped out by jug music, discarding the kazoo and novelty/entertainment side of things and bringing a soulful depth to proceedings that hinted at the original material to come.

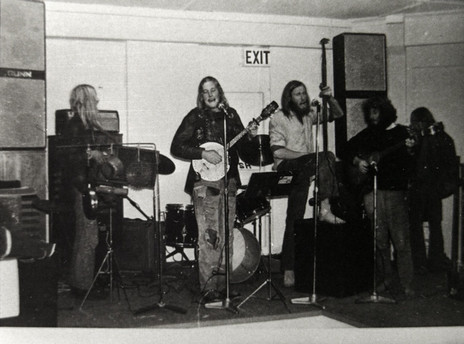

Windy City Strugglers, at the National Folk Festival, Wellington, 1969 (L-R): Rick Bryant, Mike Rashbrooke, Geoff Rashbrooke, and Bill Lake. Still struggling in 1995 (L-R): Andrew Delahunty, Bill Lake, Rick Bryant, Nick Bollinger, and Geoff Rashbrooke. - Nick Bollinger Collection

“My brother Mike and I met Bill Lake in auditions for the Kelburn International Airport Ceremonial Guard Band,” says Geoff Rashbrooke. “We played very rough kazoo and washboard. The band didn’t last long, but we formed the connection with Bill.” The Strugglers’ influence stretched to wayward youth in the north, where you could find teenage Graham Brazier’s mysterious punk-jug outfit the Greasy Handful. In Costa Botes’ crucial documentary Struggle No More (an intimate look at The Strugglers from 2006), Brazier tells a tale of the Handful making a late gambit to return home to Auckland after a pilgrimage to Wellington to see their heroes, getting stranded overnight and nearly freezing to death in that hitch-hiker’s hell northwest of Palmerston North, Bulls. Such was the conviction of a Strugglers fan.

Kelburn International Airport Ceremonial Guard Band, August 1967. Back row, from left: Mike Rashbrooke, Geoff Rashbrooke, Bill Lake, Simon Morris. Front row: Steve Robinson, Mitch Park, Lindy Mason. - Steve Robinson Collection

The Windy City Strugglers were the first of the jug bands to start writing their own songs. Geoff married, took advantage of access to his wife’s piano, and over time became the group’s excellent pianist, and the band continued to evolve and carried on for decades. Bill Lake established a songwriting partnership with Arthur Baysting, and the band eventually got around to releasing an impressive handful of albums, achieving well-deserved late success with their 2005 CD Kingfisher which saw them reaching wider audiences internationally and touring Europe.

Railway Pie

Formed in Palmerston North in 1969 and comprised of a blend of Manawatū locals and out-of-towner university students, Railway Pie played a fair bit with the Strugglers, both in a folk capacity and alongside them in a mid-70s electric metamorphosis. The large folk and blues contingent around Massey University had their own source of sought-after sounds in the form of Neville Pickett’s store, The Record Hunter. Along with conventional import avenues, one of the enterprising Pickett’s sources for fresh LPs seems to have been the airmen and crews coming in and out of Ōhakea Airforce Base.

Railway Pie and the Best Bets performing in an early gig at Beethoven's, Palmerston North.

“He was very astute at figuring out what people wanted to hear, and he knew the guys on the base very well,” says Railway Pie’s Jim Crawford. “I mentioned the connection to him back in the day, and he didn’t deny it…”

Four of the original Railway Pie members still play live and are recording their third album. Popular Wellington jug-folkies The Kelburn Viaduct Municipal Ensemble Jug Band – which boasts Neil Worboys, ex-Bulldog Bill Wood, Maurice Priestley, and storied folkster Carol Bean – has featured ex-Pie member Derek Burfield in the line-up. Neil also plays in the Hogsnort Bulldogs Goodtime Band with skiffle-pop band Hogsnort’s singer and former Bulldogs manager Dave Luther.

Black Soap Boys, 2013 (L-R): Chris Grosz, Rick Bryant, Gordon Spittle. Kelburn Viaduct Municipal Jug Band, 2021 (L-R): Maurice Priestley, Neil Worboys, Carol Bean, Barry Carter, Bill Wood, Peter Gregory.

Original members of Stupid Cat Requiem recently played an informal reunion in Whanganui. The Black Soap Boys featured Rick Bryant, Chris Grosz, and Gordon Spittle, while Smokestack boasted Grosz alongside Railway Pie’s Jack Craw. It has always been fairly common for old folkies to pop up in new configurations, perhaps reflecting shared attitudes and folk club origins (and it’s fair to say, New Zealand’s smallish population and geographic scale plays a part), but there’s something about the jug band background that sets these characters apart and binds them together.

At Jack Dusty's, Otumoetai, Tauranga, 2024: Robbie Lavën, left, and Mike Garner. - Sally Garner

Bear in mind also that the groups featured here are a only small sampling of the many jug bands in Aotearoa in this period. Jug music is essentially rural, born out of hard work on the land and the need to share a good time at the end of the day. Pākehā university students of the 1960s may have been a million miles from Memphis of the 1920s, but many of them came from farming backgrounds, and with its ties to the protest movement, folk music provided a way to reconnect to aspects of those roots while discarding conservative socio-political associations.

As well as protests and political rallies, jug bands were always part of the entertainment at the hugely popular National Banjo Pickers’ Conventions which attracted 3000 attendees to its final event in 1970, attesting to the scale of this cultural phenomenon. The depth of recognition and attraction to jug music, to that particular sound, was strong enough to stomp up a booming echo across New Zealand that still resonates today.

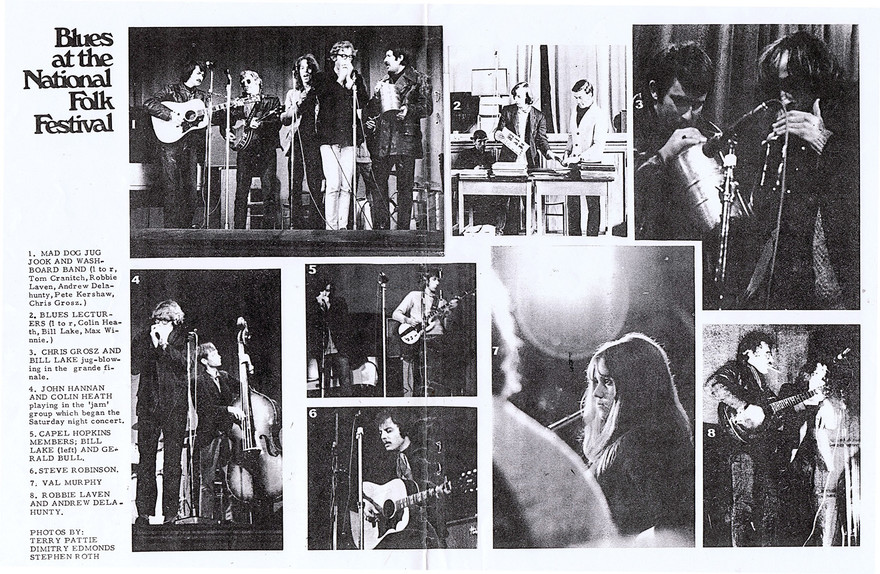

Blues at the National Folk Festival, Wellington, 1969: Mad Dogs and Windy City Strugglers. - Blues magazine