Talk to anyone who moved in Auckland music circles at the time of the late 60s “blues boom” and it won’t be long before you hear the names Henry Jackson and Peter Kershaw.

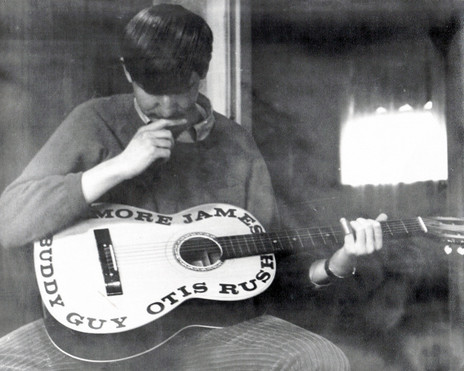

Henry Jackson, 1966-68

Henry Jackson’s first hero was Hank Marvin. So enamoured was he of The Shadows’ lead guitar player that his first band, formed with a bunch of fellow Mt Roskill Grammar students, was named after an early Shadows tune, ‘Jet Black’. The Jet Blacks’ repertoire consisted mostly of material by The Shadows, supplemented with other guitar-led instrumentals by six-string twangers such as The Ventures and Dick Dale. Then The Beatles happened, and the other Jet Blacks – a fluctuating line-up that at one point included future Minister of Police, Ian Revell – started lobbying to introduce Merseybeat material into the repertoire. Henry, as lead guitarist, found it less interesting to play.

Henry Jackson, centre, in the Jet Blacks.

He stayed on for the sixth form while the remaining Jet Blacks left school and the group soon broke up. But Mt Roskill was swarming with other young musicians, including guitarist Lou Rawnsley and drummer Tony Walton, who would go on to form The Underdogs, guitar-slinging brothers Jack and Dan Stradwick who led The Action, and a guitarist and bass player named Peter Kershaw.

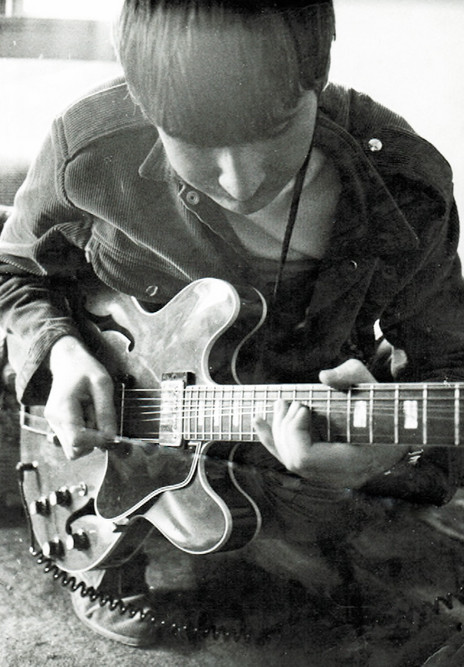

Peter Kershaw.

Peter Kershaw came from a musical family. His uncles had been part of the Auckland jazz scene in the 50s, and from a young age he attended monthly parties at his grandmother’s place where local musicians would party and play all night. “My job was to sit in front of them, keep their glasses full and watch their fingers.”

By age 14 he was being called on to play bass for dine and dance gigs. The older musicians would be “yelling out the chords and I’d have to listen and follow. It was the standards, all the old things I’d heard all my life. I’d wash and iron my white shirt and tie and one of my parents would drive me to the job and I’d have to get home myself. Then go to school.”

Kershaw was listening to more contemporary sounds as well, and he bonded with Henry Jackson over a shared interest in some of the rougher blues sounds coming out of Britain around that time: The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds, and The Pretty Things, whose New Zealand visit in 1965 made a particular impression on Henry. Though most people remember the tour for the drunken antics of drummer Viv Prince, Henry’s abiding memory was that Prince, although “a complete drunk, no question,” was also a fantastic drummer.

Kershaw and Jackson were also becoming curious about the music’s African-American origins, spurred on by Jackson’s younger sisterElissa, a blues fanatic in her early teens whose collection included records of Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and a rare bootleg of Robert Johnson.

Henry Jackson with his Gibson ES 335 guitar, 1969.

Jackson began importing Black American blues records from Shreveport, Louisiana music shop owner Stan Lewis, and struck up a friendship with British record collector and blues scholar Paul Vernon, who would send him records and reel to reel tapes of rare blues recordings. Deciding his Hank Marvin-style Stratocaster was not the right instrument for the blues, he bought a Gibson 335 from Tony Rawnsley, brother of The Underdogs’ Lou Rawnsley. Now at university, Jackson’s initial attempts to start an electric blues band with Kershaw foundered, but a chance meeting in the University of Auckland quadrangle with an accomplished guitarist and singer named Tom Crannitch and a washboard player, Paul Tucker, led to the formation of an acoustic group, The Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band.

Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band, 1969: Peter Kershaw in front. - Photo by Susy Pointon

Through Tucker, Kershaw heard about a 1930s model steel-bodied National resonator guitar, the iconic country blues instrument played by early bluesmen like Bukka White and Son House. It belonged to an employee of Tucker’s father. “He didn’t know where he got it from but he used to take it to parties. You could open beer bottles on the F holes and hide behind it in a fight.” Kershaw persuaded him to swap it for a 12-string guitar, convincing him that the 12-string was louder. Kershaw began teaching himself bottleneck guitar tunes on the instrument, which he would play with and without the Mad Dogs.

The Mad Dogs continued for the next few years and included at various times such notable musicians as Robbie Lavën, Chris Grosz and Andrew Delahunty, and were sometimes joined by guest singers such as Marilyn Bennett and Jenny Parkinson (later of The Fair Sect and the musical Hair).

Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band, at the National Folk Festival, held at the Wellington Polytechnic, October 1969. From left, Tom Crannitch, Robbie Lavën, Andrew Delahunty, Pete Kershaw, Chris Grosz.

Jackson’s focus remained on forming an electric blues band, an idea that finally crystallised in mid-1967 when he teamed up with a pair of blues-playing brothers from Titirangi, Ron and Alastair Riddell. With Kershaw on bass they became the Original Sun Blues Band. Initially a four-piece, they played occasional concerts at the University of Auckland and were a staple of the blues nights at the Montmartre nightclub. After a while they added horn players to the line-up, one of whom was Adrian Cotter or “Cotter the Potter” as Henry remembers him: a Titirangi resident like the Riddells, who went on to become a well-known ceramicist. The other horn player, John Wynyard, doubled on saxophone and trumpet. Gigs with the horn players had a tendency to spiral into long, loose, free-form jams.

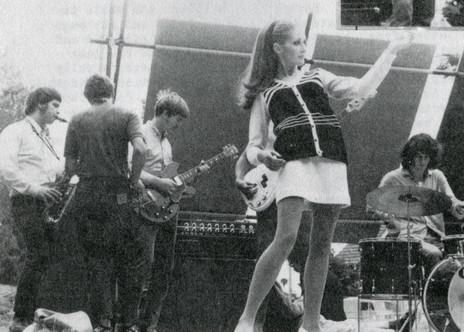

Killing Floor at the First National Blues Convention, 1968. - Photo by Steven Roth, Blues News, issue #1.

Killing Floor, playing at a fashion parade, Auckland University (L-R): Andrew Kimber, Bryan James, Henry Jackson, Ron Riddell. - Photo by Steven Roth, Blues, issue #2.

In 1968, Alastair Riddell and his friend Selwyn Jones organised what they grandly named The First National Blues Convention, the prototype for what would become a series of all-weekend, proto-rock festivals at Moller’s Farm in Oratia. Jackson and Kershaw performed in their new band, Killing Floor; the emphasis was still on blues as the name, taken from a song by Howlin’ Wolf, suggests. A Second National Blues Convention took place in December 1969, using a more psychedelic title, The Electric Picnic.

Advertisement for the Second National Blues Convention, Moller's Farm, Oratia, 27-28 December 1969. From Blues, issue #4

Richard Taylor was recruited on drums, John Tanner on bass, with Kershaw playing harmonica, slide guitar, rhythm guitar, and vocals. Both Jackson and Kershaw were paying occasional visits to Wellington, which had its own thriving blues scene and where they had friends with common musical interests. But on returning to Auckland after one solo trip to the capital, Kershaw discovered he had been replaced in the group by a new singer recently arrived from Huntly, Alan Hunter. Though Hunter would later become one of New Zealand’s most respected country singers, his vocal hero at the time was Cream’s Jack Bruce.

Killing Floor first line-up, 1968 (L-R): Andrew Kimber (back), Rob Britain, Henry Jackson, Pete Kershaw, Bryan James, John Tanner. - Henry Jackson collection

Killing Floor had also added horns, inspired by the way these were used in contemporary groups like the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Jackson met saxophonist Bryan James by chance. “I was wandering down the road one day with a B.B. King record under my arm, a bit like Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, ’cause I was importing records and he saw it. ‘Hey, what are these records?’” James brought along Andrew Kimber, a second saxophone player.

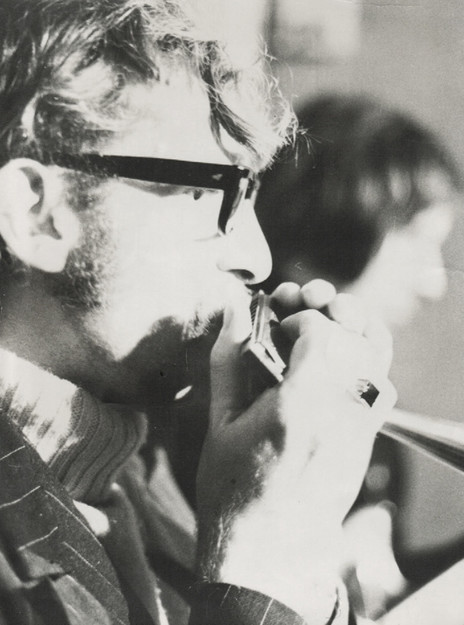

Members of Killing Floor at University of Auckland, 1969: Bryan James, Henry Jackson, Andrew Kimber.

Killing Floor found sympathetic ears for their uncompromising repertoire at the Lime Street Blues Club, held every Sunday at the Wynyard Tavern, and the Underground Blues Club, which Jackson ran with his sister at the Coffee Cellar in Elliot Street. It was difficult and sometimes dangerous work trying to introduce the blues to the uninitiated, and there were moments when Killing Floor’s name was almost too apt. A gig in Gisborne during Easter 1970 erupted into violence between locals and visiting surfers, who seemed more intent on bloodshed than boogie. Jackson recalls a few of the fighters, in between throwing punches and bottles, shouting at the band: “Hey man, dominate the gain!” meaning “Turn up the volume!” in an apparent attempt to weaponise the music.

Scarier still was a party for engineering students in a rugby shed at the University of Auckland. Ominous signs met the band when they arrived in the afternoon: there was sawdust on the floor and chicken wire surrounding the bandstand. One student was already spreadeagled on the ground in a drunken coma. Bottles and vomit started flying as soon as they played their first notes. The band were thankful for the chicken wire.

Killing Floor, 1968 (L-R): Pete Kershaw, John Tanner, Andrew Kimber, Rob Britain, Bryan James, Henry Jackson.

Killing Floor added a trombone to its horn section and was briefly joined by pianist Paul Hewson, who later found fame with Dragon. But the interests of the musicians, including Henry Jackson’s, were beginning to diversify. When Killing Floor ended in 1971 he formed Dog Breath, an experimental band dedicated primarily to performing the music of Frank Zappa. Though Dog Breath was short-lived, Jackson remains proud of how well they mastered some of Zappa’s challenging time signatures and complex structures.

Cruise Lane in the Embers courtyard, 1972. Left to right, Peter Kershaw, Tony Pilcher, Al Hunter, Claude Radics, Paul Lee. - Al Hunter collection

Meanwhile, Kershaw had taken a job with Cruise Lane, the resident band at Embers nightclub, replacing the group’s founder and bass player, Jerry Biggs. Among the other members of the long-running and frequently changing line-up was Alan Hunter, who by this time was married to Kershaw’s sister, Shirley. The gig was a marathon: six nights a week, starting at 10pm, usually finishing up some time around dawn. They would also fit in a couple of rehearsals each week, and sometimes a daytime concert or guest spot at another club. The repertoire was huge – “I kept hundreds and hundreds of songs in my head” – and the club’s owner, former folk singer Nick Villard, encouraged the band to write and play originals. He also ran cables from the PA system to his office enabling him to jam with the band. “You’d be on stage playing and suddenly you would hear this slide guitar and voice coming through the PA!”

Embers was a favourite haunt for visiting sailors. For Kershaw, residency at “this scummy little place that had fights every night and blood on the stairs” was “the most wonderful time of my life”. In the early part of the evening Cruise Lane entertained a regular mix of punters, but later on at night “it was all the strippers from Karangahape Road, the escorts, the prostitutes, the working girls, transvestites – just wonderful, friendly, generous, kind people. There were never any fights when they were around. It was just when the Australian ships came into Auckland that the trouble started.”

One of Cruise Lane’s extracurricular gigs was opening for Australian chart-toppers Daddy Cool in an outdoor concert at Carlaw Park. Inspired by the Joe Cocker / Leon Russell Mad Dogs and Englishmen extravaganza, the group was augmented for the occasion with extra keyboards and a large vocal auxiliary, which so impressed Daddy Cool’s management company, Sparmac, that they suggested Cruise Lane shift base to Melbourne. In the end only a small contingent made the trip: Kershaw, Hunter, drummer Claude Radics and manager Rhys Walker, plus keyboardist Alan Moon, who Kershaw had lured away from BLERTA. Vocalist Kaye Wolfgramm, Hunter’s female foil, stayed behind as she was pregnant. So was Shirley Hunter, and after a few weeks with no work and only the rudiments of a band, the Hunters returned to Auckland and family life.

Meanwhile Henry Jackson continued in the experimental direction of Dog Breath with his next group, Oktober, who performed mainly at the University of Auckland campus. The line-up included future Hello Sailor members Graham Brazier and Lisle Kinney on vocals and bass respectively, a violin player, and occasionally two keyboards. He recalls that one of the keyboard players was a heroin addict, the other partial to amphetamines. Their contrasting chemical conditions meant they were inclined to play at different tempos.

Jackson also retained his interest in blues. He had been a co-editor of Blues News (see The Blues Zines), and continued to write about music through this period, contributing occasional pieces to the student paper Craccum and the national music mag Hot Licks. By this time, some of the blues players he admired were starting to tour New Zealand and his writing credentials opened doors for interviews, though he now cautions “never meet your heroes”. He found Freddie King, prior to showtime, sprawled on a hotel bed, dressed in a bathrobe and more interested in ascertaining whether his fee had been paid in advance than talking about music. Muddy Waters, too, was “a little bit remote” though he let Jackson try out his Fender Telecaster while some of his sidemen looked on and muttered bitterly about how “you white guys would rather hear Jeff Beck play than us”.

He encountered Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee pre-concert, in a backstage bathroom. “I was in the stall and when I came out there they were, fighting! One had a stick and the other was blind, but they were going for each other.”

Guitarist Henry Jackson's band Cherry Pie, circa 1974. Henry is rear right, others include John Tanner (left rear) and Richard Taylor (front left). Cherry Pie released one Rhys Walker produced single for the Direction Records label.

On a 1973 visit to San Francisco he met Rolling Stone co-founder Ralph J Gleason, a veteran music critic who had started out writing about jazz in the 1950s and by the mid-60s had become a proselytiser for the psychedelic “San Francisco sound” of the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and their ilk. Jackson liked Gleason very much, though they argued about white blues. Jackson championed the guitarist Mike Bloomfield whom Gleason dismissed as a derivative B.B. King imitator, while venerating the Dead’s Jerry Garcia.

On the same visit Jackson attended a New Year’s Eve concert at Daly City’s Cow Palace featuring the cream of the then-current Southern rock movement: The Marshall Tucker Band, Charlie Daniels Band and the Allman Brothers. He didn’t stick around for an early-hours guest appearance by Garcia; by that time the Oakland chapter of Hells Angels had begun prowling the aisles wielding pool cues and it seemed like a good time to leave. On his return to Auckland, inspired in part by the Southern rock sounds he had heard, he founded Cherry Pie. Though the group was short-lived, they cut one single, ‘Lightning Red’, the first example of Jackson’s music to be preserved on record.

Peter Kershaw and John Tanner in the first line-up of Killing Floor.

In Melbourne, Peter Kershaw and Alan Moon made ends meet playing standards as a duo, then joined a local band that was looking for a bass and keyboard player. The group, Key Largo, would be Kershaw’s main gig until 1977 when Robbie Lavën, who Kershaw had played with in the Mad Dogs, arrived in Melbourne with his eclectic combo, Red Hot Peppers. Tired of the pub circuit and enticed by Lavën’s plans for concerts and recording, Kershaw joined a Peppers line-up that included guitarist Mike Farrell, drummer Neil Reynolds, and vocalist Marion Arts, all New Zealanders. The band released several records and made some high-profile television appearances, but their music proved too eclectic for mainstream tastes. By the end of the decade Kershaw had put his musical career aside for a job in the film industry; he spent the next 28 years working as a grip.

By this time, Henry Jackson was also living in Melbourne. Though music had been his main preoccupation as well as his livelihood, he had also been studying educational psychology at the University of Auckland. After the economic downturn of 1973 it was becoming harder to live off his guitar playing and when he found himself working full-time as a car park attendant, the academic life began to look more attractive. Academic scholarships had also been affected by the downturn, so on a supervisor’s recommendation he relocated to Melbourne where he began working towards a doctorate in educational psychology at Monash University. To support himself through his studies he joined a band, Rollercoaster, fronted by Australian bluesman Alex Burns, and stayed with them until they broke up in 1979. By this stage he had become deeply absorbed in clinical psychology, which led to a position as Head of Psychology at Royal Park Psychiatric Hospital. Playing music fell by the wayside for at least a decade.

His work has centred on the development and assessment of new psychological treatments for psychotic disorders, and factors affecting functional recovery and quality of life in psychotic patients. For a number of years he worked in partnership with Professor Patrick McGorry (2010 Australian of the Year), developing an early intervention research paradigm. This has led to a world-wide change in thinking about intervening in young people with psychotic disorders and in youth mental health service delivery systems. He retired in 2014 and that year was made an emeritus professor.

In the 1990s he began to pick up the guitar again, feeling “there could be more to life than research articles and patients with unusual diagnoses”. He took jazz lessons and started playing with younger jazz and funk oriented players, including the outstanding drummer Danny Fischer. In the early 2000s he formed Portmanteaux, a funk / reggae / rock group focusing on original material, which continues to this day. It is just one of three music projects he is currently involved in. There is Another Story, a duo with Portmanteaux colleague Steve Malkin which specialises in atmospheric, cinematic-style music, fusing electronica with some of the sounds Jackson remembers from his West Auckland childhood: Hank Marvin, Ventures, even touches of Māori showband. And there’s Otis Slim Sundown, a creation that touches base with his lifelong love of blues. Though this started as a solo project, in recent years he’s been recording under this name with his old Mt Roskill bandmate, Peter Kershaw.