New Zealanders are known for their ingenuity and many local musicians have taken novel musical approaches to achieve international success. This creative attitude extends to local inventors and entrepreneurs, who have come up with some innovative gadgets to aid and inspire music makers in their creative process. This list attempts to capture some of the broad range of musical products that are designed, and often built, here in Aotearoa.

Sshhmute

Sshhmute designer Trevor Bremner and his wife Betty, with musicians from Wynton Marsalis’s Jazz at the Lincoln Center Orchestra.

Trevor Bremner has received awards on both sides of the Tasman for his cornet playing. When he settled in New Plymouth to raise a young family, he realised how essential it was to have an effective mute to minimise disturbing his wife and children. However, the mutes on the market didn’t work well for him. A few years later, he decided to design one of his own.

“There are two main aspects to a practice mute,” says Bremner. “One is that it plays in tune – if you play out of tune, it has an overall effect on the quality of the music that the performer is trying to project. The other is having a free-blowing action and making sure that when you are playing it doesn’t feel like you have a mute in at all. A mute that is free-blowing does not alter the muscles in the embouchure. I took all of these factors and applied them to the Sshhmute.”

Sshhmute for trumpet/cornet.

Finding a solution took three-and-a-half years of trial and error. At first he used the materials at hand, such as pieces cut from suitcase material and solid brass, then these were later swapped out with different grades of plastic to make them lighter. He started assembling the mutes by hand from his home in Brisbane, Australia, while he was still teaching music in the local schools. Bremner sent mutes out to professional players around the world and was overwhelmed by their enthusiasm.

The workload soon reached a level where he and his wife, Betty, left their Brisbane-based jobs and moved back to New Plymouth to start producing the Sshhmutes in large quantities. Bremner, now aged 80, has retired and the business is currently in the safe hands of Betty and their son, Fraser, with Scott Susans looking after the assembling of the mutes. More than 95% of their orders go overseas, selling to over 35 countries.

Their range now covers eight different brass instruments. There’s also an onstage Whisper mute and their version of a straight mute: the Sshhtraight (available for trumpet/cornet only). A lengthy list of some of the world’s best brass musicians endorse their mutes, including Joseph Alessi (principal trombone, New York Philharmonic), Australian jazz multi-instrumentalist James Morrison, globe-trotting trombone soloist Christian Lindberg, and bands/ensembles such as the Foden’s Band (UK champion brass band) and Canadian Brass. Trevor and Betty’s son David is the principal trombonist of the NZSO and has been effective in converting other players in the orchestra to his parents’ mutes too.

Synthstrom Deluge

The Synthstrom Deluge.

The Deluge provides a tactile and intuitive way to create synth sounds, write beats, and record the outside world. The unit is the brainchild of musician Rohan Hill. His early bands made indie guitar music rather than electronica, though he did make MIDI music for his own computer games at high school. He then studied computer science at Victoria University of Wellington and gradually he applied this knowledge to his music – when playing as a drummer, he hooked a device to his guitarist’s loop pedal so it would play a click for him to follow and then when he played guitar himself, he hooked up a MIDI controller foot pedal to his laptop to add a broad range of digital effects.

Deluge creator Rohan Hill (left) and at right, Ian"Blink" Jorgensen.

In January 2014, he drew a design for a sequencer, initially planning for it only to work with other instruments. He built a prototype in his bedroom and shared it online, where it was seen by his friend Ian Jorgensen (A Low Hum). Jorgensen offered to help him turn it into a viable product and arranged for local musicians to provide feedback.

The final design of the Deluge took all the possibilities of digital music-making and put them into a stand-alone device with its own engaging interface of inputs, buttons, and knobs (certainly better than staring at a device screen). Synth sounds and melodies can be sequenced over beats or put alongside samples from outside sources. This is made possible by the “piano scroll” layout of the main keypad, which makes it clear which elements are making sound at any time by showing them light up vertically down the main panel.

Thousands of Deluge units have been sold to customers across the world and they now have a team of seven at their Wellington factory. Jorgensen has taken a grassroots approach to marketing the device, by touring with it as an electronic artist himself, arranging user parties around the world, online festivals, and multiple compilations featuring other artists making music with it.

Serato Pitch ’n Time

Serato's Pitch 'n Time

The astounding story of Serato also begins with a computer science student at university, though this young inventor came up with his idea before he’d even graduated. In 1997, Steve West was trying to work out how to slow down songs in order to learn their bass lines. However if a song is simply slowed down, then the pitch of the music also changes, which means working out the notes is impossible. The existing software created to fix this problem produced very poor results, so West created a far more effective algorithm.

One of his fellow students at the University of Auckland, AJ Bertenshaw, proposed that they turn West’s algorithm into a business. The pair got investment from their parents and launched Serato early in 1998. They quickly moved from licensing the algorithm to creating their own Pro Tools plug-in. The pair promoted it by attending conferences around the world and gained decent sales via word-of-mouth.

However it would require the backing of a far larger company if Serato was going to reach its potential. After being rebuffed by multiple big players in the music industry, they finally signed an agreement with Sony Pictures Entertainment. Since then it has been used by both top film-makers (David Lynch, George Lucas) and chart-topping musicians (Fatboy Slim). The Pitch ’n Time was an international success story, but Serato wasn’t done yet.

Serato Scratch Live

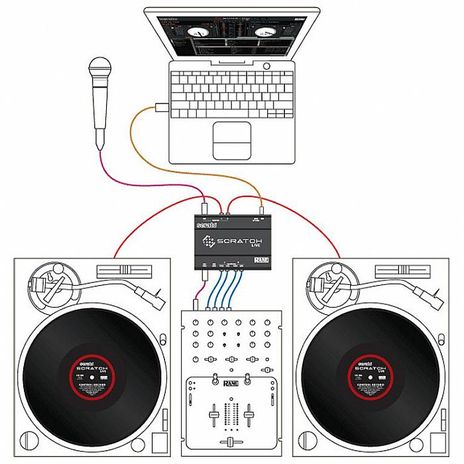

Rane Serato Scratch Live SL1 USB Interface

Serato next turned its attention to another problem – how can DJs avoid having to take the full weight of their vinyl record collection to each show? Obviously the easy answer is to switch to playing digital files, but then there’s no way to interact with the music via a turntable, which is a skill that DJs have turned into a serious art form.

In 1996, James Russell was at the University of Auckland researching digital ways to replicate the DJ scratch technique. One key problem was how to track where the record was in relation to the needle at any given time so scratch noises added to the audio file would match. Steve West suggested using a control tone, so Russell incorporated this idea into his research paper.

The pair came back to this idea in 2001 and created a Pro Tools plug-in named Scratch Studio Edition, which allowed users to “scratch” audio either by manipulating a record or using a mouse. Then they created a version that could work live, incorporating the full range of cutting and scratching skills of a DJ, and took it to the NAMM (National Association of Music Merchants) and arranged for a DJ to demonstrate how it worked. However their DJ was unhappy with the mixer they’d chosen and suggested sourcing one from the company, Rane, who was also showing at the convention.

This led to two crucial developments. First, Steve West met one of Rane’s top engineers, Rick Jeffs, creating a connection that would lead to Rane and Serato working together. Second, word spread that there was an innovative new bit of DJ kit being displayed and soon there was a raft of legendary DJs crowding around their display, including A-Trak (the first DJ to win the ITF, DMC, and Vestax competitions), J Rocc (Beat Junkies/Madlib) and Babu (Beat Junkies).

Serato and Rane collaborated to create Scratch Live, allowing DJs to carry their whole set on a small hard drive and manipulate the tracks using a physical record – mixing and scratch as they always had. The influence of Serato has since reached a level where both Eminem and Kanye West have referenced the company in their raps.

Melodics

Melodics Keys.

Melodics is game-like software that teaches users how to play electronic keys, pads, and electronic drums. Sam Gribben founded the company in 2014 after 10 years as CEO of Serato. During this time, he noticed how common it was for producers to tap drum beats using their keyboard or hit-pads. The idea behind Melodics was to create purpose-built software so that self-taught players could practise hitting notes in rhythm.

Melodics initially focused on finger drumming, where people use their fingers to tap out a beat onto a pad controller (a 4x4 set of pads that can each be assigned to a drum sound). They then moved on to MIDI keyboard players, which saw an even bigger uptake by users. In this case, the software set-up presents notes coming vertically downward and in line with the correct key on the keyboard.

A version for drummers, using an electronic kit, shows the notes scroll horizontally across the screen in a similar position to where they would be on drum sheet music, with cymbals at the top, snare in the middle, and bass drum at the bottom. In each case, the notes onscreen turn green if hit on the beat. Their latest update allows users to play popular songs across all available instruments. As Gribben told the Business Is Boring podcast: “what if we could make it so that practising to play an instrument was actually fun?”

Gribben’s prior connections helped in getting Melodics off the ground and soon they had purpose-built lessons given by DJ Jazzy Jeff and Butch Vig, as well as the ability for the software to integrate with instruments from over a dozen major instrument manufacturers. Their modern, gamified approach to learning also put them in a strong position during the pandemic when appetite for at-home music education hit an all-time high. No doubt, Gribben won’t stop until rappers are dropping the name of Melodics in their raps too.

The rise of Melodics and Serato has seen Karangahape Road turn into a worldwide hub for music technology, especially given that the area is also home to Algonaut (a local company whose product Atlas allows for AI-powered sampling); the international company Inmusic also has an office here with dozens of staff.

Musical Electronics Library (MEL)

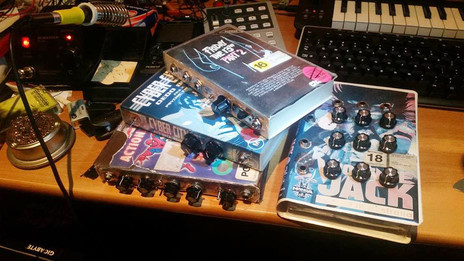

A set of effects units and sound generators for the MEL collection.

Innovation doesn’t always have to take place on the international level of Serato or Melodics. Here’s an example that centres on fostering creativity at a grassroots level. The key person involved is Pat Kraus, who makes mind-warping psychedelic music as a solo artist, though he has also played in influential bands such as The Aesthetics and the Futurians.

Kraus started out on guitar, bass, and drums but gradually took an increasing interest in modular synthesisers and built his own from component parts, which led him to the idea for a musical instruments library:

“After teaching myself to build electronic circuits, I was looking for a way to use this skill to help my musical community. I had heard of toy libraries, and around 2013 I read about tool libraries being established in the US and Britain. A musical version of this seemed like an excellent idea. I started to build some circuits, and initially was going to run the library out of my house, but Zoe Drayton, the founder and then-director of Audio Foundation [in Auckland], suggested that I host the collection there.”

The main instruments available through the Musical Electronics Library (MEL) are modular sound generators and effects units. These were built during a working bee of local musicians, who put together a range of these devices using old VHS cases to house the electronics. Anybody who signs up to the Audio Foundation library can loan these units to use for their own projects.

Since then the collection has also expanded to include other donated pieces of gear such as guitar pedals, keyboards, and drum machines (as well as a couple of beautiful vintage synths that people can use on site). The MEL has now been running since 2014, though Kraus recently passed on management of the collection to Eamon Edmundson-Wells and Sean Martin-Buss.

Ekadek

Greg Brice from Ekadek with one of his creations: a dual-channel tube limiter with four band transistor filter equalizers, a standalone mastering unit.

Ekadek specialises in creating custom-made builds for musicians and studios. The products are all inspired by vintage, analogue approaches to recording, so the electronics are based on transistor and tube technology to make a big fat clear sound.

These range in size from small units (preamps, eqs, limiters, 4-track mixers, spring reverbs, tape echoes etc) through to whole consoles. They all have the same minimalistic look – plain metal faces with labelling stamped into their surface and the most utilitarian of switches and knobs. Surprisingly, the result is a range of equipment that is remarkably beautiful to look at.

Ekadek is the brainchild of Greg Brice who started his career at Last Laugh Productions, a studio in Vulcan Lane (Auckland) in 1982. He recorded acts such as The Kiwi Animal, Fetus Productions, Marie & The Atom, Peking Man, From Scratch, and the Schmeel Brothers, before working at the University of Auckland and then moving to Melbourne in 1989. He then says he “lived and learned and wasted my thirties making music and films and shows and cars and recording gear.”

In 2001, he returned to New Zealand and started Ekadek. Since then, Ekadek has become legendary among sound-o-philes in the music scene with clients across the world, from the US to Asia to Europe. There are even two studios which have been largely constructed around his equipment: Bevan Galbraith’s Bagnall Hill studio in Te Pahu, and Sound Recordings in Castlemaine, Australia (run by Australian Alex Bennett, previously in New Zealand band Raw Nerves).

Ekadek equipment at Sound Recordings studio in Castlemaine, Australia. - Photo by Alex Bennett

Some of New Zealand’s most well-respected musicians are ardent users of Ekadek equipment. Dave Dobbyn has said he was “thrilled and inspired” by his Klanka unit from Ekadek and Nathan Haines gushed that the preamp he got from Brice has “character and warmth and those magic extra harmonics you only get from great gear.”

Ruban Nielson from Unknown Mortal Orchestra is also a big fan of his Ekadek Kaimatron and, around the time of his album Multi-Love, he said of the unit: “it’s really amazing how many different tones come out of this thing, from clean and clear to fat and warm to fizzy and aggressive … this thing has become a centrepiece and I’ve done everything on the new album through it.”

Saxmonica

Saxmonica

From its name alone this one will grab the attention of any wind instrument player.

The Saxmonica was created by Nick Millington, who liked the idea of having a saxophone that could be carried easily. He’d started toying around with a saxophone mouthpiece which he connected to a length of pipe. It sounded intriguing so he decided to see if he could make an instrument that worked, using the tin whistle as a basis for the fingering.

He set up a Kickstarter campaign hoping to sell a couple of hundred of them and instead sold thousands, so he knew he had a real business on his hands. His next move was to travel the world, selling the instrument to different distributors to create a distribution network for the Saxmonica.

The selling point of the instrument is not only its transportability, but also the ease of learning it so it provides a nice entry point for young musicians who are interested in picking up a wind instrument. It has its own app so that users can learn to play from 30-second instructional videos then play to backing tracks, without requiring a teacher or music book.

The same breathing technique can be applied to more traditional instruments such as saxophone or clarinet. Even an experienced player will get a kick out of suddenly being able to produce this wonderful little instrument out of their pocket whenever they feel like having a blast. The company has now shipped Saxmonica to over 80 countries and Millington continues to travel the world, spreading the word of his invention.

Crowther Hot Cake

Paul Crowther with the Hot Cake. - Gareth Shute

Let’s give credit to New Zealand’s most iconic pedal, which inspired many of those who followed – the Hot Cake.

Paul Crowther first made a guitar pedal back in 1967, following the diagram in a magazine to create a basic fuzz unit. He took his love of electronics into the bands he played with in the 1970s, building a modular synth for Eddie Rayner to play in their band Orb, before becoming the resident electronics whizz for Split Enz after he joined as drummer in 1974. He made an experimental distortion unit for Phil Judd, then an even more unique idea came to him:

“It was one of those cases where you instantly know it’s quite a good idea. Noel [Crombie] used to crash around onstage with a guitar, playing nothing in particular. So I built a unit into his guitar. He said ‘it sounds a bit professional for what I’m doing’ and I agreed, so I put a classic fuzz into his guitar instead. Though I kept that idea and made a couple of distortion pedals for people in England. After Split Enz, I played with another group there so I made one for the guitarist.”

When Crowther returned to New Zealand, he refined this approach and began making more pedals for friends and selling them in local stores. As with all distortion pedals, the aim was to replicate the warm sound of an overdriven amp, but at a quieter volume. Crowther managed to achieve this effect while retaining more of the notes played, so that the melodies rang through more clearly.

In the meantime, Crowther had joined Jeff Clarkson’s band and they were looking for a name. Doug Rogers from Harlequin Studios suggested “Hot Cakes” which Crowther realised would suit the pedal he’d invented. The Hot Cake remained largely a local phenomenon throughout the 80s, with many Flying Nun bands incorporating it into their sounds. However in the early 90s, US guitarist Henry Kaiser bought one and showed it to Ken Fischer, who wrote about it in his column for Vintage Guitar magazine. This kicked off an international mail-order business for Crowther.

There were offers from overseas companies to manufacture them but Crowther continued making them in his home workshop, with his Joanne loading each circuit board. Crowther wires each one up himself and tests it individually. Despite this low-key approach, Crowther does hear of his units being used by some of the world’s top guitarists:

“When the Rolling Stones were here to play Western Springs, I got a call from Keith Richards’ guitar tech and he gave me some cash and some tickets in exchange for a Hot Cake … Noel Gallagher has used one. Neil Finn still has the one he got off me in the 80s. Another time, someone sent me a photo of Mark Knopfler’s mic stand with a Hot Cake sitting at the bottom of it. He ended up using it on the album he did with Emmylou Harris.”

Crowther eventually discovered that some guitarists were using two Hot Cakes strung together, which led him to create the Double Hot Cake. He also investigated how the overtone harmonics caused by a distortion pedal could lead to some fascinating new types of sound and this led to him creating the Prunes and Custard pedal (heard clearly on the Liam Finn song ‘Better To Be’). It was so well-loved by guitarists that the description on its label even spawned its own song: ‘Harmonic Generator’ by The Datsuns.

Boogie Juice

Lastly let’s look at a more quirky family-owned New Zealand business: Boogie Juice. The original idea came from Simcha Delft, who was still living in Britain at the time. Delft reasoned that it would be easier to clean and oil a fretboard using something similar to a marker pen, with a nib that could wipe the inner of each fret. After moving to New Zealand to work at Begg’s music store, Delft became a luthier. Arranging distribution for Boogie Juice through music retailer Lyn McAllister, she eventually decided to sell rights to the product as a going concern.

Ownership of the product went through a couple of different hands after this, though without gaining much profile. Finally Lyn McAllister encouraged one of her reps, Ed Lancashire, to take over the product, so he bought the rights from the then-current owner (Alistair Cuthill from Alistair’s Music in Wellington).

The Boogie Juice team at NAMM, 2019: Lucy Lancashire, Roz Lancashire, Phil MacEwen, Alan Lancashire, Eddie Lancashire.

Ed Lancashire worked hard to turn Boogie Juice into an international product, with customers across Europe, Asia, and the US, while arranging with his old company Lyn McAllister to distribute it in New Zealand. His son Alan also helps out with the business and says the name of the product is often what first catches the eye of customers:

“They love the name. We’ve been to NAMM for eight years in a row – excluding the Covid years. People of all nationalities come past our stand and say – ‘Boogie! What does it do?’ Then when we demonstrate it to them, they can see the nib allows you to get right into the gaps – it’s precise and there’s no scratching of the fingerboard. It nourishes, it oils, it’s easy to use, and it’s clean.”

The Boogie Juice pen.

Since Ed first took over Boogie Juice around a decade ago, it has become a part-time business for various members of his family and each pen is put together in a workshop on family property in Lower Hutt. Alan says that most of his close relations have been brought in to help at some stage:

“Ed turned 87 the other day, so for the last couple of years I’ve been running it with him looking over my shoulder. When we go to the NAMM show, the family goes. On the stand with me, I’ve had my sister, my stepmother, my brothers and their children. My daughter was 17 when she did her first NAMM show, we had to get dispensation for her to work on the stand!”