Solomon Pōhatu was a teenage multi-instrumentalist from Muriwai, just south of Gisborne, when he joined a group of young Māori musicians in the late 1950s. They called themselves the Hi-Five Mambo, and evolved into the Māori Hi-Five.

“Solly hails from Gisborne,” says his pen portrait in the programme for a 1963 national tour by the Māori Hi-Five. “He is a dapper young entertainer who has been in show business since he was only five years of age – at this very young age, he toured with his parents in a Māori show. King Solly, who is now 21, has an extensive repertoire which includes bass, piano, sax, guitar, drums, and he is a lead vocalist. He also has uncanny abiilities as a mimic and because of this he has earned for himself the title of “the New Zealand Sammy Davis.”

Small in stature, “King” Solomon – aka Solly – stood out for his confidence, humour and his sheer talent. A natural mimic, an early nickname was “New Zealand’s Little Richard”. Besides singing R&B and jazz, he lip-synched to Stan Freberg comedy records. In 2010 he said that performing came naturally to him: “All the shyness was knocked out of us when we were pretty young … there were lots of occasions around family, on the marae, where you were called in to perform. It was all part of making us who we were.”

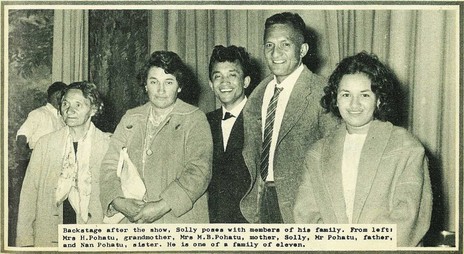

Solly Pōhatu backstage at the Gisborne Opera House with members of his family, 1963. From left: Mrs H Pōhatu, grandmother; Mrs M B Pōhatu, mother; Solly; Mr Pōhatu, father; and Nan Pōhatu, sister. - Gisborne Photo News, 18 April 1963

In 2004 Piripi Walker interviewed Pōhatu for a series he made for Radio New Zealand on the Māori showbands, when many of the veteran entertainers gathered in Wellington for a reunion, and Matiu Baker of Te Papa had created an online exhibition. This is a transcript of that interview. In the early 1990s Pōhatu and Walker worked together at the Wellington iwi station Te Upoko O Te Ika, where Walker was the manager and Pōhatu a very popular host (later, Pōhatu was a host on Radio Ngāti Porou). Solomon Pōhatu died in 2018. – AudioCulture

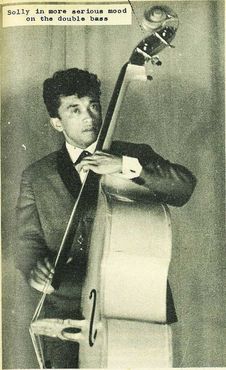

King Solomon Pōhatu entertains Gisborne. - Gisborne Photo News, 1963

Your main instrument is the piano. You added others later on, like the guitar and clarinet, but can I take you right back to those early days, your childhood, starting to learn music and the piano and who taught you?

Early days for me in music was through our families with parties that we had. Because for me that was only form of entertainment. Having no electricity out where I was brought up, and only having the radio on – because there was a battery thing – between the hours of maybe six and maybe 7.30pm, and that was your lot. And you might have it seven o’clock in the morning – so music was always a hunger for us, as young people I felt. I basically learned from our koroua and kuia that were there. ‘Chopsticks’ was the first thing I learnt to play on the piano, and then I moved on to the ukulele. And when I was 10 or 11 my uncle came home and he had a tenor sax. And he used to go to teach us, he was a school teacher and when he used to get home I used to try and rush home before him ... so I could spend my little practice thinking that he didn’t know. Now, being a lot older, I realise he was doing it for a reason. He left the saxophone out for me to do exactly that, so eventually when his band called the Crazy Cats started playing if one of the members couldn’t make it for some unknown reason, he would come and get me and I would end playing second tenor or third tenor with the band or whatever, so that was my only teaching.

And the comedy, you’re identified as a natural mimic, did your family regard you as a comedian at an early stage?

Yeah, I think our people basically on the marae, watching a lot of our kaumātua, you know the way that they expressed themselves on the paepae, in those days there were phenomenal things. I’ve seen phenomenal speakers, I’ve seen them spit and do different things that people nowadays frown upon but those were my tūpuna, and consequently the way that they express themselves, I mean if they came on, the speaker ahead, he would turn his hat backwards, and we all automatically knew by that sign, that the person before him was a liar. (Laughs) So the comedy came because of all of those little things, and I think that one of the greatest things for us living in the country, you had to have some form of ... and coming from a large family, I’m the oldest of 11, brought up by my grandfather who had a family of 14, so there was a lot of people around so you had to have some sense of humour being there. Comedy to me is right through to this day a part of life, you’ve got to have it.

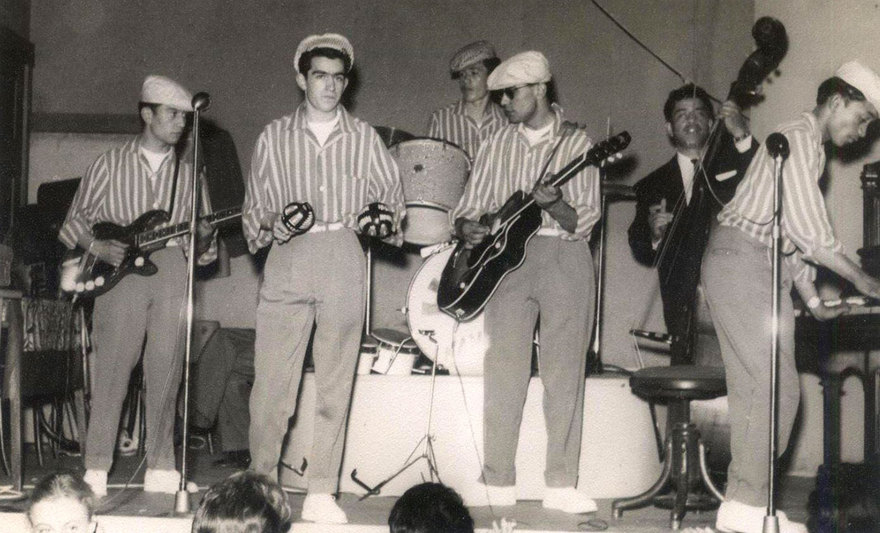

The Hi-Five Mambo in Whanganui, October 1958: Ike Metekingi, Costa Christie, Jimmy Rivers, Rob Hemi, “Fro The Pro” (a guest), and Sol Pōhatu. - Costa Christie collection

Some of the people looking at the show bands success later say that one of the real magic ingredients was the natural comedy. Would you agree with that?

Yeah. I mean it comes up, it came up with people like Tui [Prince Tui Teka] and it came up with Hector [Epae] and all of those people it came and I think showbands ... to me “showband” is just Māori entertaining. That’s all it is. It’s just that we added a few instruments and added a few routines here and there and a few harmonies, which we normally do in our parties at home or now our kura kaupapa, and this is all coming out as natural. That’s what showbands were and how they were created, because it was created thru wanting to present something that was a bit different. Other than singing ‘Pōkarekare Ana’ and ‘E Hine hoki mai ra’ and all those things – which we still did, you know, in the shows there.

You’re noted for your falsetto and they called you New Zealand’s Little Richard. Can you talk about the influence of rock and roll.

Well, Little Richard, back in those days when we started off at the Cuban [Club Cubana] here in Wellington ... Little Richard’s ‘Lucille’, ‘Long Tall Sally’, were popular things, and being a young pianist type thing we started doing those things as well. I think that for most of my years I’ve been a mimic in a lot of different things. I can hear something and put it out and bring it out so I think it’s just part of our trying to grasp an identity for yourself without really knowing what you want to do (laughs), or if that expresses or identifies anything.

And of course, I’ve heard you sing Hawaiian songs.

Yeah I love Hawaiian music.

You were there for quite a while.

Twenty years I lived in Hawaii. The greatest thing for me was meeting some Hawaiian people before I went to Hawaii. And when we worked in Hawaii with Frankie Stevens, I was Frankie’s road manager. He replaced me in the Hi-Five when I moved to Hawaii, and the people who I met when I lived on the island lived on the island of Maui, so naturally they kind of adopted me within that family, the Luuwai family over there. And then you hear the real Hawaiian. You lived with the Hawaiians and heard the real Hawaiian and I saw a lot of what I saw with our people at home. The only difference was they had an American accent. And then they had this pidgin English which we have at home anyway.

Paddy Tetai, Mary Nemmo, Wes Epae, and Solly Pōhatu - Gisborne Photo News, 18 April 1963

Actually I remember you when you came back from there, I related to you culturally you were very Hawaiian in your ways weren’t you?

Yes I was. When I came home I had a tough time with our language because I had Hawaiian in my blood and in my brain and in my heart. Becase I just felt so much a part of them. And it was not only their reo which is similar to our reo, and learning their ways and their music. It took a long time, but eventually came right.

Your choreography that you developed for the Hi-Five’s stage act and so on, did you teach yourself or have mentors in that department?

Yes we had, er, we were fortunate, our management structure brought us through, started here in Wellington with Jim Anderson and Charles Mather. When we got to London we were sent to music teachers and dance teachers. And one of the greatest teachers I ever had, he was an American negro, Buddy Bradley, through him he started teaching the soft shoe shuffle, modern jazz ballet and tap. And so consequently with all the moves he was teaching, by the time he was teaching he was about 78, about that age and the moves he was making ... Well Wes Epae and I became the front with Mary Nimmo at that time. And we learned a lot from that, you know tap dance moves, so those things came, we learned a lot from that, in seeing other groups dancing especially in Las Vegas you see some of the best performers. That’s where the dancing came in to the production, was worked out.

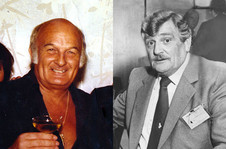

Charles Mather and James "Big Jim" Anderson.

You just mentioned Charles Mather, an interesting character, ex-English, a Royal Marine. Can you describe what he was like to meet?

Yeah he was a very jovial man, Charlie was a manager up at the Skyline Restaurant in those days when we first met. He was the one that actually came down to the [Wellington] Trades Hall when we were playing in the Hi-Five. Oh he was up at the Cuban first and then we moved to the Trades Hall, and he actually formed us into a showband, through his expertise working with the Marines and putting on those big shows that they have. So Charlie stayed with us all the way through, very much part of our family today, he lives in Las Vegas, and Kawana Pohe of the Hi-Fives is still there.

And you’re all in contact?

We’re all in contact yeah through email, thankfully, that email. We call it tane but it’s the same. (Laughs)

Well this Te Papa exhibition will be ideal for the international community that you are. On line on the internet.

I think it’s a brilliant thing, it’s got to be a plus for our people, our young people, I hope it’s a plus. I brought along a young protégé, he’s working with me, he plays 10 instruments. He’s an arranger, a conductor, and we’re getting him to sing tonight, a young boy, Hemi Porou. He’s related to me through the Bartlett family out at home. But I just want to encourage young people to look at what we have done, and where we’ve gone. And hopefully with this [showband exhibition] website we can encourage them to try that, do the same thing, we hope it’s not going to be an end, what’s happening today and tonight continues on.

The Māori Hi-Five at Caesar's Palace, Las Vegas, late 1960s. Back row, from left: Paddy Te Tai, Mary Nimmo-McMullan, Peter Wolland, Wes Epae, Rob Hemi. In front, Kawana Pohe and Solomon Pōhatu. - Lou Kewene-Doig collection

It’s a positive, that would sum it up, the whole industry that came with the showbands, for all of you that were involved, a positive for you?

I think it’s a positive thing because if you look at the record of it, you wouldn’t find any negatives from any one of the members within the show band community. There’s hardly any negatives in it whether it’s drugs or whatever. And the positive side of it is that lot of is that a lot of us actually stayed within our own selves and we were actually ambassadors for our own people, and our culture and for our country. And so I think there’s a lot of positives to look at.

Solly Pōhatu in 2016, from the Waka Huia profile directed by Tina Wickliffe. - Waka Huia/Scottie Productions

There was a really marvellous entrepreneurship that was happening. The identification that this kind of opportunity existed. In Australia for a start and then the world. Would you agree with that?

It was. Well, in the beginning there was different times I suppose, but at the Trades Hall what we did was, when we knew we were going away we brought in other groups behind us, the Hi Quins, and another group behind them and another group. We paved the way for those groups and they followed us, throughout the training that we did and travelling overseas. A lot of them got over to Europe and America, the world. I wish we could try to keep it going here now because there’s a lot of our talent that’s being wasted. I know that and I’m sure a lot of them out there know that. You’ve just got to keep trying.

Solomon e te rangatira tēnā ra koe.

Kia ora.

--