Beware! Reading this does not guarantee you instant commercial success and a new car. And it’s also doubtful that once your sponge-like brain has absorbed all the gritty information waiting here to be divulged that you will run up to your guitar or piano and instantly create a string of perfectly crafted songs.

On the other hand, maybe you will ...

The purpose of this article is to plunder the brain of New Zealand’s most successful songwriter, Neil Finn, in order to uncover any secrets or shortcuts he may have worked out writing for Split Enz and Crowded House.

Crowded House, 1993 (L-R): Nick Seymour, Neil Finn, Mark Hart, Paul Hester. - Grant Thomas Collection

Not surprisingly, there are some common parameters. Neil admits that he can’t get very creative when his head’s bothered by the dull book-keeping of life, but on the other hand an impending deadline will encourage him to work harder. He also often struggles for hours over a few words and yet confesses to generally placing more importance on a lyric’s musical melody than its meaning. And like everybody else he suffers writer’s block and occasionally wallows under the gloomy cloud of self-doubt.

Maybe the biggest gem he offers up to us here is that it’s okay – liberating, even – to cast an idea into the bin.

So whether you write jingles, anthems or thunderclaps of melody, here’s a look into the tune-filled head of Neil Finn ...

--

Getting straight to the point, can you tell us how you write songs?

The moments when I’m most creative are when I’m sitting there with nothing to do and nothing pressing – no one’s making demands on your time. This is just me, so I can’t talk for anybody else. Even the most angst-ridden songs tend to get written when I feel okay. I don’t normally write when I’m really depressed. Just clearing out space mentally is the first step.

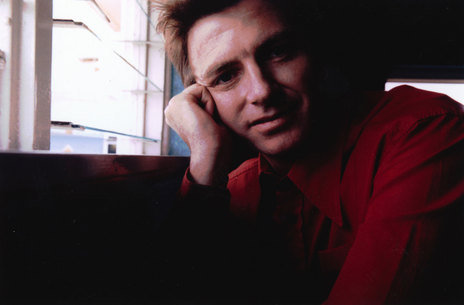

Neil Finn in 1998 - Photo by Zoran Gold

I was talking to [the late Chills frontman and writer] Martin Phillipps about that the other day and he said the same thing. Usually before he goes away to write he makes sure he pays all his bills, gets all his stuff tidied up, so when he gets there he’s got nothing playing on his mind. I guess that’s because it requires getting into a slightly trancey kind of state, which is easier once you’re undistracted.

What sort of material were you coming up with before you joined Split Enz?

I wrote a few things when I was about 15, mostly because Split Enz asked me to go on tour with them, so I had a focus for it. It was kind of boogling on the piano. When you start off you’re playing other people’s songs hopefully not too accurately, so that you get their style as well as their content and you get an idea of how chords fit together and things that you particularly like that seem to reflect something essential in you.

Split Enz, 1980 (L-R): Neil Finn, Tim Finn, Nigel Griggs, Eddie Rayner, Malcolm Green, Noel Crombie

It’s much the same as doodling on a piece of paper, when you’re not thinking about it and all of a sudden, when you look at it, it looks like a face or something. The first step is kind of the unconscious step, for me. And it was the same then as it is now. Just burbling pretty absentmindedly on the piano or the guitar until you come up with something that feels good to play. And usually with me the chords will suggest a melody. You find yourself la-la-la-ing and a phrase will drop into your head.

The longer you can keep it not fully conscious the better, in a way. Because as soon as you become conscious of what you’re doing it becomes an academic exercise. It’s easy to talk yourself out of it at that point and say, “Well, thinking about this logically, it doesn’t seem all that crash-hot.” Whereas if you go about it without questioning it and just let it be, all of a sudden one chord, or one little thing, will change and the melody will shift and suddenly it has a little bit of a life. Up until that point it’s just pure will – an act of will. But a lot of the time, I find, when I’m writing, it’s just a case of believing you’ve written a song.

If you’re in a negative frame of mind you’ll go, “That’s nothing”, and disown it. But on another day, when you’re feeling a bit more positive, you’ll take it through and you’ll demo it and at some point it will come to life and you’ll go, “Wow! This is really good!”

All the practical things like a deadline and a purpose, someone to bounce it off pretty soon after you’ve written it, are important. Or better still, to play it in a band room, when what is just a couple of chords and a little riff idea can suddenly become a three-hour jam – which is totally uplifting. In the course of ranting your way through a jam you can work out all the lyrics and the different bits.

Do you record these ideas in their first instance or do you try to remember them until you’re jamming with the band?

It’s good to have a tape recorder all the time because often the structure or the rhythm of a line is at its best the very first time. If you’re not recording it you can easily lose a couple of beats of the rhythm and then suddenly it’s really ordinary – it’s that subtle, sometimes. So if you’ve got a recorder going it’s very useful to be able to refer back to how it was when you first started and keep that in mind as the soul or the essence of the song.

Crowded House at Karekare, 1993 - Youri Lenquette/EMI

And anyway, the more you sing it the more you change it. It’s OK to evolve it to a point, but I think you’ve always got to get that first performance down on tape. I don’t always do that, and there’s an argument for saying, “Well, if it’s good enough, you should be able to remember it.” Sometimes you can be lying awake at night and a great thing will come into your head so you sing it over and over again to try and remember it … but in the morning it’s gone. That’s really frustrating. I’m not very good at keeping a tape recorder handy all the time, but that would be a great attribute for a writer. Or a notebook for that matter. The moment might strike at any time.

It can happen that I’m at somebody’s house in the middle of a tour, I’ll find an hour of peace and somebody’s got a great piano and a nice room and you go in for a private play. That’s quite common, to be in a different location and feel inspired just because you’re in a different room.

It is deeply mysterious because there are probably exceptions to everything I’ve said. Because there is no textbook on writing songs, it is useful to have a few things that you observe yourself and become a slight form of discipline as a way of getting into the right frame of mind. But ultimately things pop in when they’re ready to. An emotional event happening is usually quite good for dislodging a few lines, but I rely on subconscious for some of my stuff.

Some of the Enz stuff was quirky; the Crowded House stuff actually has some jarring moments. Do you have any particular favourite formula?

I’m aware of certain formulas that I inevitably fall into, because they’re chord progressions that do something for me. So it’s kind of a battle to write in a style which people like, and you like, without repeating yourself. A few songs on different albums are very similar, although there’s a different spin on each one. But I would now be aware that I should avoid certain things because I’ve done them too much.

Crowded House - Together Alone (Capital Records, 1993)

A classic example is ‘Nails in My Feet’, from Together Alone, which has very similar chords and melody to ‘Fall at Your Feet’, on Woodface. No one has pointed it out, but when I made the connection I considered leaving out ‘Nails In My Feet‘. But sometimes the arrangement can make it sound totally different. Anyway, rock music has repeated itself ad nauseam and it’s only the character of the singer that differentiates something from the last thing that happened. Certain riffs have been recycled billions of times. It’s all in the character and the attitude. There are people who are original, but they’re few and far between.

How many songs do you write for an album?

For Together Alone we had about 25 songs. I don’t tend to finish things unless they’re reasonably good, so I’ll just have lots of ideas floating around. When the band’s played them, we can get an idea of which ones work well. Then I’ll finish them.

What comes first, music or words?

The music always comes first. Sometimes it comes with a chorus line, which can be as little as one phrase and is basically the essence of the song, or it can be as much as the whole lyric. Music and lyrics occasionally happen together, and they’re usually pretty good those ones. Whatever lyrics I come up with at the time – and often they seem like nonsense lines and phrases just falling out of my mouth – you have to look at them and figure out what they suggest, before you get too hung up about what they mean, and find other lines that match them in atmosphere and intent. Or even provide a jarring counterpoint.

The more lyrics you get to write at the same time as the music, the better, because you’re never going to get into the same atmosphere as when you wrote that song. It’s like pulling teeth – every new line is very difficult. The prerequisite for me is that they sound musical, they sound good to sing, and that’s above and beyond whether or not they mean anything. They must have a satisfying feeling to sing. And what bugs me more than anything are songs where there’s emphasis on a word that you just wouldn’t put emphasis on. It might be a nice line but the emphasis is on “the” or in a really weird place in the line, so it totally screws up the rhythm of the song. The craft of it, for me, is to get the words to sound musical.

I wish sometimes it was easier. There are certain people I know who just scrawl words out – bang, bang, bang, bang, bang – then they pull the best ones and they always sound great. On a really good screeds-of-lyrics day that might happen to me, but more than often I’ll dish up about seven or eight lines, maybe 10, that feel really right and are the essence of the songs and the rest of them I have to slave over for hours sometimes.

Do you ever get writer’s block?

Yeah, at times. When I think about it, it bugs me that I don’t write every day. Months go by where I don’t write a thing. A lot of it is because I don’t even try. It just doesn’t feel right. It’s just laziness really …

Maybe you’re not hungry enough …

It usually needs a deadline of some sort, something looming, to actually make me sit down in a really disciplined way.

But if that deadline comes up and you’re not firing, do you get frustrated?

It’s pretty troubling and difficult for those around you. You feel useless. You’re a songwriter and yet you can’t write. It’s like going to work at the bank and not being able to add up.

I don’t get as panicky now as I did. There’s a large percentage of people with careers in music who dry up after a not very long time. So when I first started I thought, maybe I’ve got a limited number of songs in me. Every time I had a block I thought, this might be it. But now I’ve been writing long enough to know that something will turn up. I just have a mild panic and then go out for a walk.

Was your first hit, ‘I Got You’, a song that you slaved over, or did it just fall into place?

Two-thirds of it was easy. I had to struggle over the last few lines, as usual, to fill the gaps in. There’re a couple of lines, to this day, that I cringe when I hear, because you end up compromising. I remember, with that one, that I really liked the verse but I was always worried that the chorus was too corny, which is probably why it was such a big hit. But I went with it and with the band it had a bit more drive to it, so it sounded a bit more happening. But when I first came up with it I thought, “The chorus has to be a bit like that, but it has to be better than that.” But it never ended up getting worked on. I wasn’t convinced it was a great song at the time; it’s probably still not, although there was something about it that people related to.

Did that song destroy any myths or ideals about songwriting you may have held up until then?

No, it created more myths than it broke down. When a song becomes a big hit like that you start to ask yourself, “What was I feeling? What was I doing the day I wrote that? What was it about that song that people connected with?” Ultimately that has to remain a deeply mysterious thing. I can point to that line “I don’t know why sometimes I get frightened”. That was a very adolescent line that a lot of people related to. It was the ultimate hook. That and the guitar riff going ding-ding-ding-ding, ding-ding-ding-ding. So you think about it but ultimately you can’t do it again the same; next time has to be something different.

It’s always seemed, to me, to be quite random and I haven’t been able to write a string of hits at any point, although over a period of time I’ve had a lot of success. It hasn’t been one after the other, just rolling them out like a Motown machine. They’ve been quite few and far between, the genuine hit singles.

Do you ever write a song and think to yourself, “I’ve got a great song here”, and then play it to the band and they don’t like it?

Not often, because I’m usually the most critical anyway. If I’ve really got this inherent feeling about a song and I take it to the band, it’ll turn out to be good. It may be difficult to arrange, but there’ll be something you know is solid. Because you know, in a way, when you write them whether they’ve got something good. Some of them surprise you, but it’s more often as a result of the band taking something you regard as being slight and then suddenly it comes to life.

It would be best to be a completely uninhibited person with a great creative spark. Doubts and insecurities tend to stifle your ability to get things out. I also feel they are responsible for me working things in the studio particularly. The craft of making a record is fed by doubts and insecurities about things not being good enough, so you try to make them better by working on them more. But it doesn’t make them better. It just makes them smoother. That’s a thing to fight against. The studio tends to make you too analytical. Trust in your first instincts in recording. That’s the best.

Do you think along the lines of verse, chorus, middle eight, and so on?

It’s tempting to. I’d like to get out of that, but it’s a very good format for popular music. Three minutes. Verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, out. In terms of keeping an audience interested, people feel good about that much information delivered at that pace.

So what is a middle eight anyway?

After you’ve done two choruses, say, there’re no exact rules, but the common pop formula is verse/chorus/verse/chorus/middle eight/verse/ chorus/out, and it’s just at a point where you’ve just had two choruses that people want to hear some little shift. The best middle eights are generally the ones where the song picks up a notch and gets really intense before opening out into the last verse/chorus or whatever…

“I feel like I’ve slightly failed, in a song, if I don’t have a chord change that was unexpected”

Because a song is such a nebulous unknowable thing, a lot of people need certain parameters to start with in order to get them into it. It’s like having a set start and a set end in a running race.

What about the claim that a hit record should have the chorus in the first 30 seconds of the song?

That’s ridiculous. As soon as you start putting forward formulas it’s narrowing what might be. Somebody’s going to come along in the next five years or so and redefine what a popular song can be, so you don’t want to give anyone the idea that it might not be them.

Over the years have you landed on chord progressions that you’re particularly fond of, or that evoke any particular moods?

I’ve ended up starting on a major and then going to the minor third below and then the major third below that, but it’s pointless talking in those terms really.

How about augmented chords?

Yeah, sometimes. Diminished chords. Augmented chords. In the right places. I feel like I’ve slightly failed, in a song, if I don’t have a chord change that was unexpected or that takes you to another atmosphere that you didn’t expect. There have been exceptions in really simple songs that just don’t change, but I’m looking for a chord change that makes you slip sideways a bit. And a lot of my songs have a minor verse, major chorus feeling to them. I like a triumphant chorus, an uplifting chorus, and a fairly brooding verse. That’s a kind of common thread.

You also use descending progressions …

A lot of descensions and stuff, yeah.

Why?

The notes start to ring around a bit in descensions. The guitar player can be playing one chord and if the bass is descending through it weird notes fly around and chords get mixed up and blurry. That’s always attractive to my ear.

Do you sometimes find that a song just isn’t working?

Sometimes the best thing you can do is chuck away hours of work and consign it to the scrap heap. It’s really liberating. It gets oppressive after a while and if you can just kiss it goodbye, you suddenly free yourself up. I find that the greatest moments in recording and writing are when you slash something, kill it mercilessly. Cast a knife into its heart and watch it squirm. I always find it really positive.

I think songs make themselves apparent. I think you know within yourself when a song has gone beyond the amount of work that it’s worth. And anyway, sometimes it’s good to chuck it; then at some point six months later you find a new way to approach it and it comes back to life. It can be an oppressive feeling to have something not working for a long time. The important thing is when you chuck something you have to get the reverse reaction to that to write something new. You have to use that feeling of liberating yourself from the curse of things not working. That’s what always works best for me, is to throw myself into something different with a lot of gusto and usually come up with something really good.

As much as you take it seriously, as if your life depended on it, be prepared to also just cut it loose and not care about it.

What about lyrics?

The other thing is not to get too academic with lyrics. As soon as you’re expecting the audience to listen to every line you’re kind of stopping them from a natural enjoyment. The majority of people just want things to wash over them and the odd line to connect every now and then.

Sad but true ...

Well, I don’t think it’s sad. I think that’s the way it should be. You absorb at your own rate. You make up your own spin. At a party you’ll sing it and get half the words wrong.

But do words you’ve written years ago sometimes make you cringe when you sing them live?

Oh yeah, sometimes ...

Do they wash over your head?

When you’re on stage you’re not thinking of what they mean anyway. It’s like playing a line on a guitar, it’s just set in your mind and you deliver it. That doesn’t mean to say that it’s lacking emotion, because the music alone can provide that. In an ideal world your lyrics mean profound things and sound really good, too. But in a less than perfect world, at the very least, they should sound good, too. That’s what matters to me. Some of the greatest rock’n’roll statements of all time have been completely meaningless.

--

‘Private Universe’ – the Dissection of a Crowded House Song

By way of putting some of Neil’s theories to the test we asked him to isolate a particularly gruesome Crowded House song, any one he wanted, and give us the rundown on how many dramas it threw up in its journey from initial conception in the songwriter’s head to the finished recorded result.

Listen to an acoustic version of ‘Private Universe’ from 1993

Neil scratched his chin, ummed and ahhed and decided on ‘Private Universe’ from Together Alone. So we grabbed it as it flew around the room, pinned its wings down on the dining table and dissected it with the rusty scalpel of investigative rock journalism. Here it is held open, its vital organs exposed to the elements and yet still breathing, as Neil remembers it ...

“I got the verse and I had it in swing feel. It was quite rollicking, going ching ching chi-ching ching, ching ching chi-ching ching sort of feel. There was something good about it but we tried it in rehearsal and it sounded too dinky. A bit too ‘good time’. And the song itself sounded darker than that, both lyrically and the mood of the chords, so it didn’t quite fit.

“So we got out to the studio and tried it all day like that. We worked on it and changed it and tried to make it happen and got to the point where we were ready to throw it away. I then remembered this chorus bit that I’d written around the same time. I changed the feel of the verse to a straighter feel, just on acoustic, strumming along and trying to get more moody with it, and it suddenly seemed to fit with this other bit. Even the lyrics that I had for both seemed to fit with each other in atmosphere, although they were written at different times and in a totally different frame of mind.

“So we stuck them together and that seemed very successful. But because we’d worked on them all day, no one had the energy to get up to a traditional band thing with it again – bass, drums and guitar – so we set up in the control room and the chorus I originally had didn’t seem like a very strong chorus, so inevitably that became the bridge, ha ha ha ha ha ha, which often happens …

“Songs do have their moments of clicking suddenly. You struggle for ages to see it. It’s like a Rubik’s cube. You spend hours of fiddling with it and fiddling with it and it just seems like it’s going nowhere and then all of a sudden there’s one turn and it’s breakthrough! Normally it takes two or three breakthroughs for a song to get to a well-evolved state. It can happen in five minutes or five days or a year.

“So we got to the point where everyone set up in the control room and grabbed the first thing they found – Paul had harmonica, Mark had slide guitar, I had my acoustic – and we got a little loop of congas going to play along, too. We tried to get into a totally fresh feeling for the song and pretty soon it had its own atmosphere.

“Even halfway through recording an album sometimes you decide that three of the songs you’ve been listening to you just can’t stand any more. So you say, ‘I can’t stand listening to those any more, they’re gone! Forget about it!’ And everyone says, ‘What? What about all the work that’s gone into them?!’ But I just find it really energising. And then you go, ‘Okay, let’s just take that one little bit out of that song. Remember that time we jammed on it and it was completely different? Let’s try to make something out of that.’ Suddenly there’s a really fresh feeling.

“That’s a great moment and that’s what happened with ‘Private Universe’. Within 10 minutes the song was a song and it was a record, too.”

--

This interview was originally published as “Codas, Choruses and Chords: Neil Finn’s Secrets of Successful Songwriting”, in The Mechanics of Popular Music: a New Zealand Perspective, by Mike and Jeremy Chunn (Wellington: GP Publications, 1995). It appears here, slightly edited, with permission.