From the beginning of the 1970s, at 348 Queen Street in Auckland, there was an unmissable sign. It read “Mojo’s Nitespot”. It would eventually become the frontage of New Zealand’s first, largest, and longest-running transexual show.

But it had an earlier incarnation. In the late 1960s, Mojo’s had been a club that had featured many New Zealand pop-groups such as The Chicks (sisters Judy and Sue Donaldson), and blind bandleader Claude Papesch playing both jazz and blues.

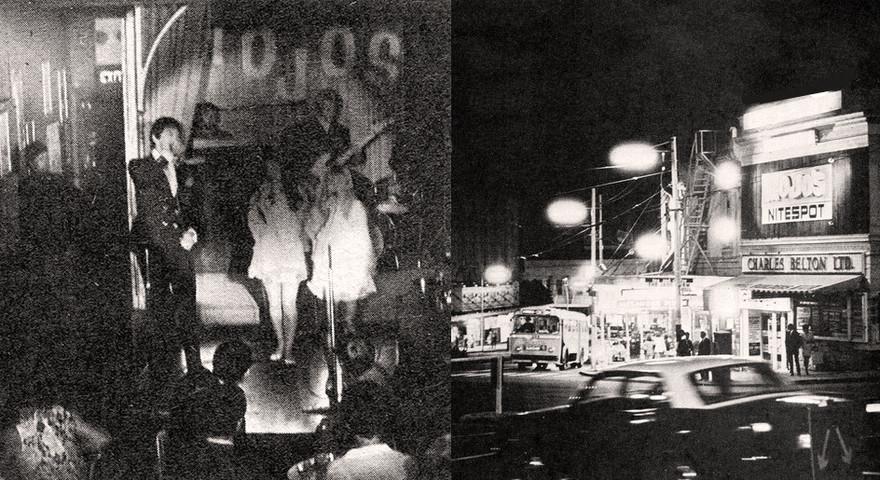

Sonny Day joins The Chicks onstage at Mojo's nightclub, corner of Queen, Rutland, and Wakefield Streets, 1969. - Playdate magazine

“Mojo’s is not a haunt for theology students,” Tom McWillams wrote in a 1969 Playdate feature. “Matt black, red lights glowing, thundering noise: although it is upstairs, Mojo’s is no celestial scene. In the dimness, walls and ceilings seem to recede and the patterns painted on the walls in luminous colour are thrown into relief.”

In 1967, Noel McKay recorded a live album in Mojo’s: Bold’n’Blue. McKay was a married cross-dressing performer, with his wife as his dresser. He had a steel corset to give himself the impression of breasts. He would always be introduced as “Mr Noel McKay” but then appear dressed spectacularly in women’s clothes, clearly influenced by film star Mae West. He changed costumes with frequency.

Bold’n’Blue was just one of his hugely successful albums. Marbecks in Queen Street, for example, sold 200 copies in one week. His risqué humour appealed to the strait-laced country of the era. In the album he was accompanied by Claude Papesch, who would endure some innuendo teasing from McKay.

But Mojo’s was limping along with falling audiences. Then in 1970, the club’s leaseholder Phil Warren found a new tenant: Jacqui Grant, an Australian-born transexual.

Grant had opened her own coffee lounge, Jacqui’s Coffee Lounge in Wellington, but suggested opening a branch in Auckland to her investment partners at the computer company, Burroughs, who had formed Wardour Investments. It was headed by closeted gay man, Bill Hornibrooke, the manager of Burroughs and the chair of the Wellington Chamber of Commerce.

With a jukebox strapped to the roof of a Mini, Grant headed to Auckland ...

With a jukebox strapped to the roof of a Mini, Grant headed to Auckland, opening a closed-door club called Lady Jacks next to the Auckland MLC building. It quickly outgrew its ability to hold 30 people. Her next venture was the Empire Room, a larger premises in High Street.

“One half was a gold cave, and the other was decorated with Greek pillars and a stage,” Grant says. “I started a drag show and got Niccole Duval to come up from Wellington to sort out the show – but to cut a long story short, it struggled on for nearly a year but financially was a big flop.”

Mojo's Nitespot, c. 1968 at the Queen St intersection with Rutland St and Wakefield St; Auckland Town Hall clock at right. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 786-A19-02 (detail)

“One night Phil Warren came in and I told him how bad it was going,” recalls Grant. “He suggested we cut our losses and move the show to a jazz club he owned on Queen St called Mojo’s. He said it had done its dash, but he thought the drag show would work there.”

At Mojo’s, the night now became a series of solo spots where artists like Tiny Tina, aka Pat Crowe, would sometimes perform songs like ‘Nobody Loves a Fairy When She’s Forty’. There was also Niccole Duval, an ambitious dancer who had worked clubs in Wellington. Mojo’s at that time was very much in the tradition of the British music hall. It slowly became more successful, even attracting sailors from the Devonport Naval Base, who were given free tickets.

Niccole Duval at Mojo's nightclub, 12 February 1975. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1269-19750215-21 and 1269-19750215-22

Niccole Duval soon left New Zealand and spent a year working and learning the mechanics of a spectacular show in the Playgirls Den in Kowloon, a part of Hong Kong, with its slogan, “Female Impersonators – Seeing is Believing”. Then she returned to Auckland.

The shareholders of Mojo’s had hired Eden Security, under Hugh Lynn, who provided security for visiting rock groups. He was to do the door and account for the money. The club itself had begun to lose money again, but Lynn could also see its possibilities. On her return to Auckland, Lynn spoke to Duval about compèring a show, should the opportunity arrive. Bemused, she agreed.

The change of owners was abrupt. Lynn had bought out the club’s lease from Phil Warren. From the start, things were different. It would become a polished, sequenced evening, very much like the club Duval had worked in Kowloon. With tables, chairs, booths, and a bar, Lynn – later a successful band-manager and tour promoter – would eventually bring visiting musicians such as Roxy Music for private events and press conferences. It also offered secure jobs for transsexuals at a time when such jobs were not common.

“Hughie Lynn took over and he brought his sister-in-law, Jenny, in to manage the club,” recalls Duval. According to Lynn, Mojo’s lost money at first, primarily because the club had no liquor licence. They tried selling alcohol surreptitiously by the glass, but that wasn’t a success, until they began selling half-bottles which people could put in their pockets to take back to their seats.

The cast of transexuals had many talents.

“We had Shona, who made many of our costumes, and Chanelle, and Nelly who were performers. We all lived on View Road, Mount Eden, all together in different flats in the same building.

“At home, we would sit working on costumes, doing the beading and things like that. Everyone got into it. Shona was the most brilliant dressmaker – you’d just show her something or tell her what you wanted, and she’d be able to cut it out and make it for you.”

A quintet of dancers at Mojo's nightclub, 12 February 1975. Standing, from left: Diana Adams, Niccole Duval, Tiny Tina, Samantha James; in front is Tanya. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19750215-14

But the club needed a unified, sequenced, show.

“I put the shows together – and they were based on what my ideas were and what I thought,” says Duval.

Lynn’s mother, Dorothy, was also the dance instructor.

“We went up to her dance studio and she taught us to tap-dance for a big production number that opened one show. She wouldn’t have ever had four queens to teach before. We weren’t professionals. We couldn’t really dance like she was used to.”

The music was from the stage musical, La Cage aux Folles ... “We are what we are, and what we are is an illusion.” It was simply one number, however. They needed more.

“When the movie Jonathan Livingston Seagull came out, I went and saw it.”

It had an aspirational plot about a young seagull cast out of his flock, produced by filming real seagulls, then superimposing human dialogue over the images. It would have some significance for any gay, lesbian, or transgendered person watching.

Samantha, Tanya, Tiny Tina (aka Pat Crowe). - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19750215-08, 1269-19750215-10, 1269-19750215-07

“The lighting guys hired the movie somehow and cut out a seagull scene that you could play continuously on a loop on a projector – [they] just cut it out of the movie!” Duval recalls, laughing.

“We did a production to it with white costumes with white capes and at a certain time Mojo’s would go completely dark and the projector would go on and there would be the seagulls from the movie flying over our capes as we moved. It really was quite spectacular.

“There was also Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells. It was all done under strobe lights. We wore bell-bottom trousers. Everything was white on one side and chequered on the other. First everything was white and then we’d turn, and everything would be chequered. It was quite amazing, especially with the flashing lights and that music!”

“There was another one where we did a sex-change. We did it all behind a see-through, gauzy curtain, all silhouetted. We operated on Kerry. She lay down and we had long rows of homemade fake sausages coming out of her and, as we cut them off with saws, we would throw them out from behind the curtain.”

“Then the curtain would open and there would be the back of this huge scallop. We’d lined the inside with all with this beautiful material that looked like pearl. Kerry would be standing in this scallop which was on wheels, and we would turn it around and there she would be, posing in a very small bikini. She had a fabulous body. She was there, almost naked. We did it to the Shirley Bassey version of ‘Sea and Sand’.”

The engrossed audience at Mojo's nightclub, 12 February 1975. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19750215-24

The show travelled to Taupō for performances, then to Tahiti where it was front page news. Lynn went with the production to Papeete where they were housed at the Pu’O’Oro Plage resort for the duration of their residency. It was a large tourist complex with thatched guest huts and a huge entertainment area boasting live music and shows. It had hosted many overseas artists, and performances were sometimes recorded for LP release. The residency was a great success and was extended. The island’s newspapers featured many photographs.

On 28 October 1971, a controversial television programme went to air. It was a documentary in the NZBC Gallery series devoted to the subject of transvestites and transexuals. It begins by speaking to two transexual sex workers working on Queen Street, discussing the hazards of their profession. The programme then moves into the interior of Mojo’s.

Performing on the chequered tiled floor of Mojo’s, the introductory clip shows the cast performing to the Pointer Sisters’ song ‘Steam Heat’ in short capes, tassels, mini-skirts, and lightweight knee-length white boots.

“An Auckland night spot, Mojo’s, and an all-male revue,” announces the reporter, Dairne Shanahan, in her voice-over, “… starring Niccole, Lee, Vicky, Cherie, Chanelle, and Brandy, all born male, but they sincerely believe that they are – and want to be treated as – girls. They are hard-working professional entertainers who strongly resent being linked with the transvestites who walk the streets.”

Niccole Duval makes an entrance with her usual flair, Mojo's nightclub, 12 February 1975. Holding her veil are, from left: Diana Adams, Tanya, and Samantha James. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19750215-11

“We were filmed at one of the front row tables – Hughie Lynn’s table – after a performance, which is why we are all wearing our stage make-up,” Duval recalls. “I can remember shooting it. Our table had a vodka and a Coke on it. I used to drink vodka and Coke, and it was my drink always.”

While clearly indicating that they live as girls, the cast from Mojo’s that Shanahan interviews still withhold information.

“We don’t have sex,” Duval says, her blonde hair caught by the TV lights as she tosses it. “We have an emotional relationship with a male, but it is not sexual.”

She points out “we couldn’t admit that we had sex because the police would have been onto us.” Homosexual sex was still punishable by up to two years imprisonment under New Zealand law and would remain so until 1986.

The programme closes with Duval performing a spectacular solo scene, lip-syncing to ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him’ from the stage-show and movie, Jesus Christ Superstar. It was a fitting finale.

Another short audio fragment of life at Mojo’s was recorded for a 1973 episode of the NZBC radio series, Spectrum, devoted to Auckland nightlife.

“It’s the only show of its type in the country,” the announcer, Jack Perkins, begins. “The entire cast is transsexual, males dressed and living as women. Their grooming and general appearance is immaculate. If you didn’t know otherwise, it would be impossible to tell them from the genuine article.”

Perkins interviews the patrons just before a Mojo’s show on a Wednesday night. They are revealing, from the very-British accents of the era to the attitudes they display.

“We are probably coming here out of curiosity,” one woman patron says, “but at the same time we’d prefer to come to this sort of place than a strip club. We don’t like strip clubs, at least I don’t – I’ve been to one.”

“Well, I’ve been to shows in Panama and Paris,” a second woman comments, “but they are so subtly done, and so beautifully done. The costumes are so good that they are not actually vulgar, and I anticipate that this probably is vulgar …”

Then there is a recorded fragment of the show itself.

Mojo's DJ and Kona coffee bar. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19750215-27

“It is with pride and pleasure,” a male voice announces, “we ask you to settle back, relax and enjoy our current show, Mission: Impossible. However, a word of warning, should anything on stage stretch or snap, our entire cast will self-destruct in 10 seconds … Ladies and Gentlemen, the fabulous Play Girls.”

It is followed by the 20th Century Fox movie fanfare and the theme music from the then-popular Mission: Impossible television series.

“The show gets underway,” says Perkins, “with the full cast performing a spectacular dance number – psychedelic lighting adds to the impact.”

As the programme progresses, Duval can frequently be heard beneath the NZBC reporter with her swift stream of patter and rapid quick-fire jokes.

During the performance, another woman patron says, “This show is much more to my taste than an all-girl strip show, which was entirely revolting. This is funny. This is slick. This is well-produced.”

However, the performers don’t get a complete seal of approval.

“They are delightful, but face up to it, get down to the nitty-gritty and they are all homosexuals.”

Then, in 1975, there was the Roxy Music reception, where the press and the band were invited to the club. Lynn was entertaining the British band with a Mojo’s show.

“They seem to have misunderstood what we’re about,” Ferry huffed, according to music journalist and writer Phil Gifford. The night was also recorded in a number of performance shots by photographer and journalist, Murray Cammick.

Duval’S last show at Mojo’s “was by invite only. I used a lot of Shirley Bassey numbers.”

“Lou Reed also came to town,” continues Duval. “Hughie Lynn was bringing all the big artists, like Joe Cocker and Lou Reed by that stage.”

“Lou Reed brought a girlfriend with him, a queen, Rachel. She was Puerto Rican, I think. Very slim and pretty. Hughie asked me to look after her for a day. I took her to town, and we did a lot of shopping. I showed her the sights.”

“We were late when we went back to the [Hotel] Intercontinental where they were staying. Lou Reed opened the door and, literally, this hand comes out and drags her in – and slams the door in my face. I think he was jealous because we were out having a girlie good time.”

There were also sometimes mysteries at Mojo’s.

“Some of the cast used to pick these men up and the next minute they’d be getting married to them. They’d plan a full wedding … They were all having phony weddings at St Matthews in the City with wedding dresses and the full bit. It wasn’t legal but no one knew they were queens. They’d all had their names changed by deed-poll at that stage.

“But with Tanya, the next thing she told us after her wedding was that she was pregnant. I went to the hospital to find out what was going on. The doctor there told me it was a phantom pregnancy – it wasn’t a baby at all.

“But Tanya insisted she’d had the baby. We went to visit her in her flat and she said that the baby was asleep in its bassinet, and she didn’t want to wake her. When she was out of the room, I looked in the bassinet and under the rugs there were rocks, arranged in the shape of a baby.”

Then, suddenly, Duval announced her last show at Mojo’s. Even now, she finds it hard to explain the reason for her final departure. Her work involved stress and constant demands. Her personal life had many upheavals.

“It was by invite only,” she remembers. “I used a lot of Shirley Bassey numbers.”

Shirley Bassey was particularly noted for her Bond theme songs – from the movies Goldfinger (1964) and Diamonds Are Forever (1971). The depth that she communicated through her voice and music certainly suited Duval’s state of mind that Sunday night.

“It was really quite dramatic,” she says of her last show at Mojo’s.

Duval would leave for Wellington the next day.

Mojo’s limped on for another year or two before it finally closed. Later it became Diamond Dogs, then Gobbles Disco. It was the end of an era for polished, rehearsed, and spectacular transgendered nightclub shows in Auckland.

--