An expatriate New Zealander in the right place at the right time helped launch British rock’n’roll. In 1956, John Kennedy was a suave opportunist in his mid-twenties who would become a clever and shameless publicist-cum-PR operative in London showbiz circles. He had, as Nik Cohn wrote, “flair, invention and a fast mouth”.

In the mid 1950s a teenage culture emerged in London around the recently opened 2i’s Coffee Bar in Soho. A plaque there reads “Birthplace of British Rock’n’Roll and the Popular Music Industry”. It was in that cramped basement that a distinctively British version of rock’n’roll was kick-started by a most unlikely singer, 20-year-old Tommy Hicks, a former merchant seaman from a working-class family south of the Thames. (Ironically, Hicks had visited Wellington in 1954 while working as a steward on the Rangitane. A hairdresser who met him at a party, where he sang, recalled, “He said that we would see his name in lights one day, but of course we just laughed at him then.”)

The 2i's coffee bar, "home of the stars" - as viewed from above Old Compton Street, Soho, London, in 1963 - CC-wiki

One night in 1956, Kennedy was drawn to the sound coming from the 2i’s basement and was smitten by Tommy Hicks’s good looks and tousled hair.

The legend – which Kennedy invented – is that after seeing Hicks sing at the 2i’s, Kennedy immediately offered to be his manager and publicist. In fact, two minor figures in London pop music were already interested in Hicks, and invited Kennedy to see him perform at the 2i’s. For years, Hicks stuck to the script, telling the BBC that Kennedy had followed him out of the 2i’s, and asked him if he wanted to turn professional. Both Kennedy and Hicks were amateurs, but Hicks said yes.

First, Hicks needed a new name. He became Tommy Steele, and – through outrageous and amusing manipulations of the British press – Kennedy made him Britain’s first rock’n’roll star. By extension, he helped create a new era in Britain’s pop business.

To help fund his hype of Steele, Kennedy turned to showbiz entrepreneur Larry Parnes, who became his business partner. These days Parnes is better remembered than Kennedy. “Mr Parnes, Shillings and Pence” was a svengali who went on to create a school of British pop stars with names like Billy Fury, Marty Wilde, Georgie Fame, Johnny Gentle, Dickie Pride, and Vince Eager. His methods were fondly parodied by Peter Sellers in his late 50s’ sketches ‘So Little Time’ and ‘Trumpet Volunteer’. But it was Kennedy who introduced Parnes to Hicks and created the wave of publicity which made Tommy Steele a household name within weeks.

From the distance of over 65 years, it can be hard to discern the truth or a sound timeline about Steele, Kennedy and Parnes, but this is what our research tells us.

In his book The Velvet Mafia, about the gay managers in British popular music – among them producer Joe Meek, Parnes, Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, and the Who co-manager Kit Lambert – Darryl W Bullock describes Parnes and Kennedy as regularly drinking together at La Caverne in Soho, a favourite venue “with journalists, drunks and many who answered to both callings.”

“[It was] a men-only establishment that featured murals of half-naked sailors on the walls and chains hanging from the ceiling, and which quickly became known as a haven for the city’s homosexuals, gamblers and theatrical types.”

After arriving from New Zealand earlier in the 1950s as a merchant seaman, Kennedy became a freelance photographer snapping the few celebrities arriving at Heathrow. When he met Hicks in 1956, Kennedy had recently been sacked from his job as a photographer for the Daily Sketch. At La Caverne he convinced Parnes to check out the young singer. Kennedy saw Parnes as someone who had the cash to launch the career of his 2i’s discovery, even though Parnes would later admit “I didn’t know what rock’n’roll was”.

“It was obvious that Kennedy had taken a shine to the young man, but a couple of years at sea had taught Hicks how to fend off unwanted attention quickly and without causing a scene,” writes Bullock.

Hicks had played skiffle in other clubs alongside others such as Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts, Long John Baldry and Harry Webb (who would soon become Cliff Richard and, like many others, also got his start at the 2i’s).

He sang songs by Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, the kids loved it, Kennedy saw his potential and made him an offer. The young singer always remembered the conversation that night:

“He said, ‘I think I could make you a star very quickly’ and I said, ‘What do you know about show-business?’ and he said, ‘Absolutely nothing! What do you know about singing?’

“I said, ‘Nothing’ and so he said, ‘Why don’t we try it?’ Which is what we did.”

Kennedy then persuaded Parnes to see Hicks at the Sabrina on Wardour Street and he too was impressed. Unfortunately, Hicks already had a management deal but Parnes and Kennedy noted he was underage when he signed, so the contract was void.

By persuading Hicks’s father, they secured the singer for a five-year contract. According to Johnny Rogan’s Starmakers and Svengalis, Kennedy was so confident in Hicks’s potential that he promised to tear up the contract if they failed to make him a star in three months. It took much less time than that.

First came the sales job: Hicks and Kennedy brainstormed a new name and settled on Steele, adapted from the first name of Hicks’s Swedish grandfather, Stil Hicks. And so Tommy Steele was born; his name was “a neat amalgam of the homely and the sexual” writes Rogan.

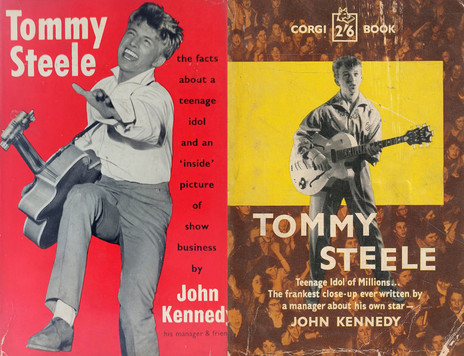

Two editions of the 1958 Tommy Steele biography written by his manager John Kennedy

Parnes the businessman bankrolled Kennedy’s publicity campaign. “Tommy had the voice, I had all the publicity know-how and Larry had a shrewd business sense,” Kennedy wrote in Tommy Steele, the quick cash-in biography he published in 1958.

Kennedy was inventive in his publicity stunts which grabbed headlines and column space in the newspapers. Before his rock’n’roll venture he had advised the stage producer Geoff Wright, who was backed by Parnes, to change the name of his failing play The House of Shame to something more racy: Women of the Streets.

The PR wide-boy hired a couple of actresses to position themselves outside the stage door dressed as prostitutes. They were arrested, the press got hold of the story – tipped off by Kennedy no doubt – and the play found an audience, although it never made any significant profit.

Because Kennedy had worked in newspapers and had run the Record Mirror’s photo studio, he had connections in the media. (In late 1954 he spent several weeks in Los Angeles, during which he allegedly photographed Marilyn Monroe on location filming The Seven Year Itch. As UK rock’n’roll historian Pete Frame quips in The Restless Generation, “Not the last John Kennedy to take an interest in her.”)

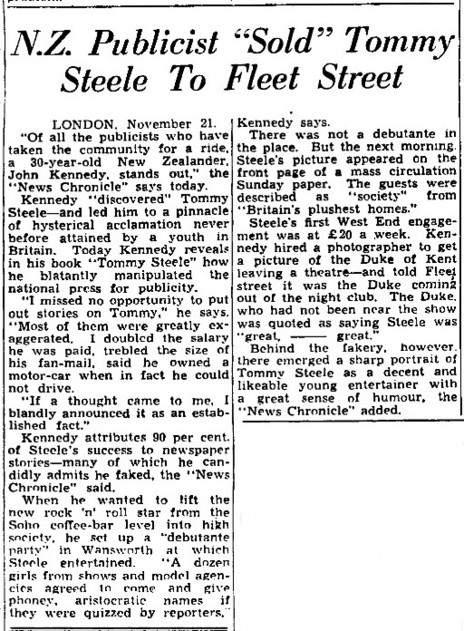

John Kennedy admitted to the publicity scams he pulled to get Tommy Steele in the papers. - Christchurch Press, 22 November 1958

Kennedy’s scams became legendary in British pop music. He had former seaman Steele perform at the Cambridge University ball which, in class-conscious Britain, guaranteed column inches.

But his most notorious stunt involved a Steele concert where Kennedy paid “a dozen girls from shows or model agencies who agreed to give phoney aristocratic names if they were quizzed by reporters”. By having them pretend to be debutantes who were fans of Steele and rock’n’roll – and suggesting this would be a good story to a newspaper editor he knew – Kennedy pulled off a show-business coup.

The story – under the block capital headline ROCK AND ROLL HAS GOT THE DEBS TOO! – appeared on the front page of The People (circulation in excess of 4.5 million). It told readers “now the smart set are at it, and here’s what the camera saw happening at the first rock’n’roll society party in London”.

Rock’n’roll, which had been associated with juvenile delinquency and Teddy boys slashing the seats in cinemas at screenings of Blackboard Jungle a year earlier, was now going mainstream and becoming acceptable, thanks to Kennedy.

“The first and one of the greatest hypes in rock history,” wrote Pete Frame. “But it could never have succeeded had Tommy not had the capacity and ambition to follow it through.” A three-week residency for Steele at the swanky Stork Club followed: “He brought the place to life,” said Parnes. “He had charisma and personality”. Journalists tracked down Steele’s interesting backstory and it was time for the singer to record something.

In one of those showbiz ironies, Kennedy and Steele were turned down by EMI’s George Martin (who would later sign the Beatles) but were accepted by Decca (which turned down the Beatles).

By chance Steele knew aspiring songwriter Lionel Bart, who – before he found fame writing Oliver! – worked as a waiter at the 2i’s. With fellow songwriter Mike Pratt, Bart and Steele knocked out the catchy if rather obvious ‘Rock with the Caveman’ (credited to Tommy Steele and the Steelmen).

The lyrics played off the 1912 story of the famous Piltdown Man hoax, in which skull fragments were said to be the missing link between humans and apes. The fraud had been exposed in 1953, so the Piltdown Man was being talked about again.

It’s not much of a song (“rock with the caveman, roll with caveman”) but it had “rock” in the title and the flipside, written by Steele, was ‘Rock Around the Town’.

A novelty song, spoof, or a genuine rock’n’roll single? It seems to have been all of those, but – at less than two minutes long – a star was born. Or at least, had been created by Kennedy.

John Kennedy tells a court that as Tommy Steele's managers, he and Larry Parnes were not overpaid. - Christchurch Press, 21 July 1960

Two days after the song was recorded in September 1956, Steele, Parnes and Kennedy entered into a management deal with Steele guaranteed 60 percent of his gross takings and Parnes/Kennedy bearing all costs of promotion, bookings, travel and accommodation out of their 40 percent.

It was a remarkably good deal at the time (Presley’s manager Colonel Tom Parker took 50 percent) and Steele was on his way. He made his television debut in late September and ‘Rock with the Caveman’ raced into the top 20. More television and live performances followed but, despite the enthusiastic fans, the music press was immune to Steele. NME said his record “lacks the authentic flavour. Best thing on the disc is Ronnie Scott’s driving tenor sax playing”.

No matter. Kennedy kept cranking the publicity machine. “I missed no opportunity to put out stories on Tommy,” he said. “Most were greatly exaggerated. I doubled the salary he was paid, trebled the size of his fan mails, said he owned a motorcar when in fact he could not drive.

“If a thought came to me, I blandly announced it as an established fact.”

As far away as Texas, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram carried a Kennedy-devised story that Steele (“Britain’s Answer to Elvis”) was earning more than the British Prime Minister.

Although Steele’s second single ‘Doomsday Rock’ (backed with ‘Elevator Rock’) was a failure, his third – a cover of the recent Guy Mitchell song ‘Singing the Blues’ (backed with ‘Rebel Rock’) – hit the top of the charts in January 1957. In the absence of much competition, it must be said. Cliff Richard’s big hit ‘Move It’ – considered the best and most authentic British rock’n’roll song – was still 18 months away.

Kennedy and Parnes saw a career for Steele beyond rock’n’roll which many felt – rightly, as it would turn out within three years – was limiting if not a dead end. As with most British entertainers, Cliff Richard being another example, the aim was to be “an all-round family entertainer” and Steele wasn’t averse to that. He had grown up with music hall songs, pub singalongs, American country and folk music. And he liked pantomime. He was by nature an entertainer.

He had a small part in the 1957 film Kill Me Tomorrow playing himself and did well enough for Kennedy to negotiate a musical bio film The Tommy Steele Story which appeared that same year. It was a fanciful dramatisation of his meteoric rise and appeared just three months after ‘Rock With the Caveman’.

The Tommy Steele Story wasn’t just a box office success and the first such bio-pic of a pop star, it spawned a tie-in album. (This included the song ‘Two Eyes’ as tribute to the coffee bar where he’d been discovered). It was the first number one album by a British act. It also secured Steele an acting career: three more films followed in quick succession.

The mythologising of Steele, thanks to Kennedy, fed directly into the most famous and impressive British pop film of the time, 1959’s Expresso Bongo starring Cliff Richard as a surly angry young pop singer on the make. Lawrence Harvey, cast as his fast-talking, hustling manager, was a distillation of Kennedy and Parnes. The young Andrew Loog Oldham who would, aged just 19, become the Rolling Stones’ first manager, saw Expresso Bongo and decided that would be his career: not the star, but the manager. Oldham saw where the power lay.

Soon, Kennedy was pulling back – Steele was too busy making films and hardly in need of publicity stunts – although he tried to make a star out of Tommy’s younger brother Colin Hicks, with no success.

Kennedy split with Steele and Parnes in the early 1960s. As Steve Turner said in the NME in August 1975: “Kennedy only wanted one star, Parnes wanted a constellation.”

A documentary on Larry Parnes featuring interviews with John Kennedy and Tommy Steele

Parnes would go on to build his stable of young pop stars with fanciful, homoerotic names. (Even as late as 1963, Brian Epstein refashioned Tommy Quigley into Tommy Quickly as he built his own roster of Merseybeat stars around the Beatles; William Ashton became Billy J Kramer, and Cilla White, Cilla Black.)

Colin McInnes satirised the pretty-boy pop phenomenon in his 1959 novel Absolute Beginners, loosely adapted into the 1986 film starring David Bowie, Ray Davies and others, which opens with a scene replicating the 2i’s. One of the characters asks about a pop song with “Which of the boy slaves was it sung it? Strides Vandal, Limply Leslie, Rape Hunger?”

The teenage market needed to be fed and the often unscrupulous puppet-masters were very happy to do it, and take the cash. Pop wasn’t art, it was the commodification of youth culture, adolescent need and managerial greed. Not cash from chaos as Malcolm McLaren would claim two decades later with the Sex Pistols, but cash from commercialisation.

Tommy Steele from Bermondsey might not have seemed to be made of star material, but he became a British show business legend. And it’s fair to say he wouldn’t have had a career if not for John Kennedy.

Larry Parnes learnt the art of manipulation and star creation from Kennedy, not the other way round. As Rogan noted in Starmakers and Svengalis, “Parnes was developing fast talking and creative skills, the equal of John Kennedy”. High praise indeed.

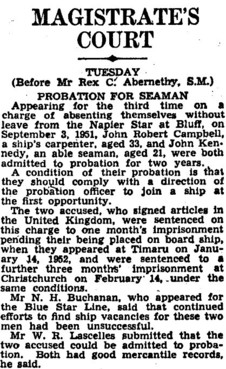

John Kennedy goes on probation at the Napier Magistrates Court for going AWOL from his merchant navy ship in Bluff. - Christchurch Press, 21 February 1952

The early, New Zealand part of Kennedy’s life remains a mystery: there’s a small paragraph in a local paper of him as an able seaman, age 21, convicted of being absent without leave from the Napier Star in Bluff and being detained for a period not exceeding three months.

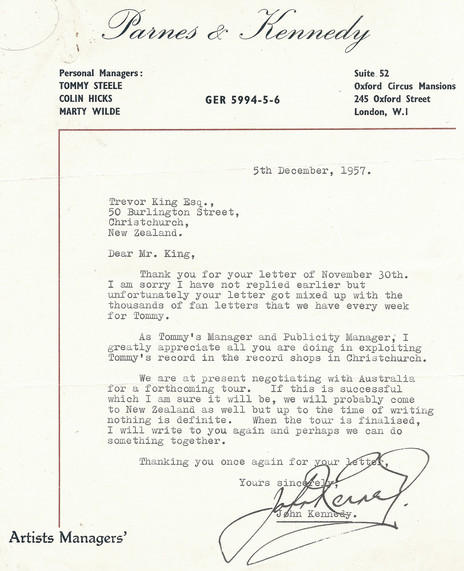

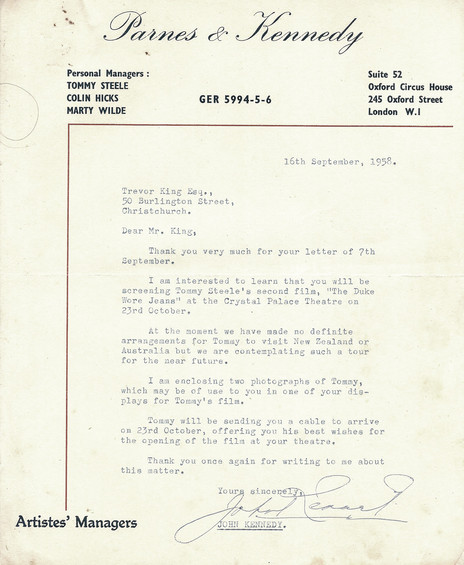

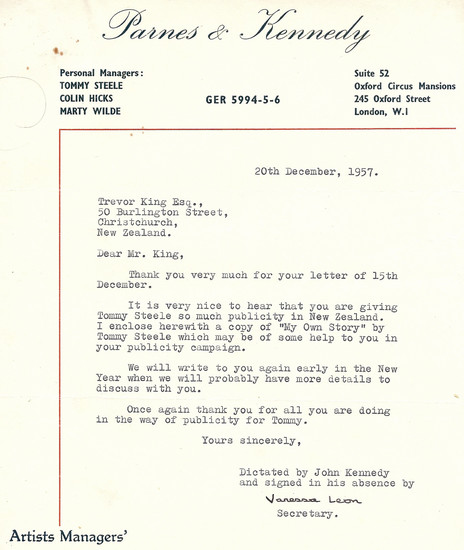

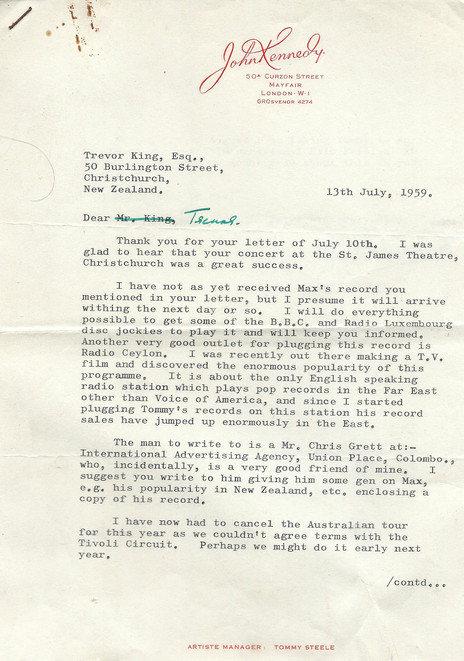

A few years later he was in Britain as a freelance photographer, and stumbling upon a guy called Tommy Hicks. His notoriety as a publicist became as big as Steele’s fame. But, after creating Britain’s first rock’n’roll star and writing a biography about him in 1958, Kennedy soon walked away from pop music. But not before legendary Christchurch promoter Trevor King, manager of Max Merritt, began a correspondence offering assistance to Steele in New Zealand, and asking for advice about how to break Merritt in the UK.

There were more headlines in 1960, when the papers reported his engagement to Colleen Field, the glamorous daughter of an Australian millionaire. In July 1960 Kennedy and Parnes won a libel action after the earlier agents who had alerted Kennedy to Steele’s talent, alleged the pair had conspired against them, “procured a breach of contract, and slander”.

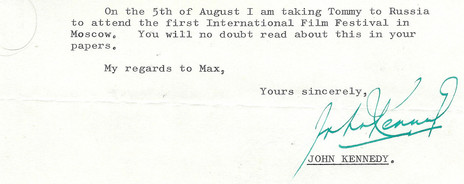

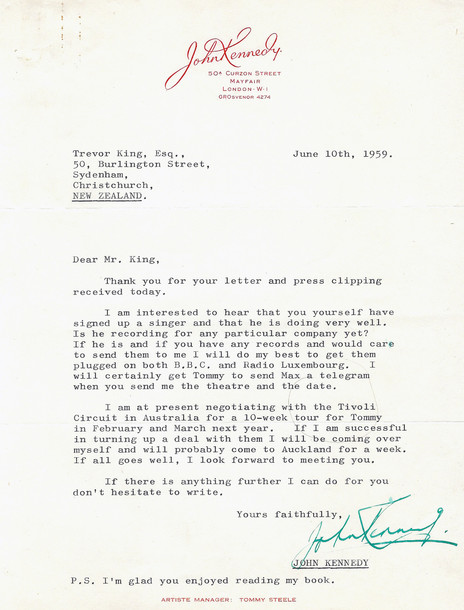

John Kennedy writes to Trevor King, about publicity possibilities for Tommy Steele in New Zealand, and for Max Merritt in Britain, 10 June 1959 (see below for more letters). - Alan Galley Collection

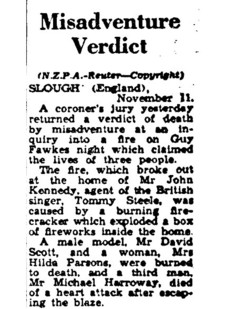

The headlines turned grim in 1961 when fire destroyed Kennedy’s wooden home during a Guy Fawkes party, after a pile of fireworks accidentally ignited. Three guests died and Carry On actor Sid James – who Kennedy was managing – was one of many celebrities present, along with buxom blonde film star Diana Dors. James rescued others from the flames but his relationship with Kennedy was never the same.

Death by misadventure: the coroner's jury returns a verdict on the Guy Fawkes tragedy that ocurred at the home of John Kennedy. - NZPA/Reuters

Three years later, in February 1964, Kennedy married London model Paula Noble, later known as owner of Swinging 60s nightclub the Ad Lib, often frequented by pop stars such as the Beatles, the Kinks, and the Rolling Stones. In June 1966 the couple had a daughter.

Kennedy died in 2004 at age 73 in California. In an obituary in the Daily Mail – which shouldn’t be taken at face value – John Edwards writes of Kennedy as being “the magician in the wings” of Steele’s rise but that he loved gambling and the good life, went to California in the early 1980s for cleaner air to assist his breathing (after decades of smoking) and started marketing air conditioning – for the outdoors.

Then he became a sculptor and “his artistry is all over the south-western states, right there in the entrance halls of banks and in special places in wealthy people’s homes”.

Maybe this is true. Maybe not. What does ring true in that obituary was that wheeler-dealer John Kennedy from New Zealand, a likeable rogue in sharply cut Savile Row suits, was unique.

“There hadn’t been a man like Kennedy before … there was this tall, slim, handsome guy strutting around, cutting deals in the offices of people who wouldn’t take a phone call from him before him. He was the first one of that kind of agent/manager, and afterwards they came along like rain.”

--

The Magician in the Wings: Daily Mail obituary of John Kennedy, 4 August 2004

Photographs of John Kennedy, Larry Parnes, and Tommy Steele

Photographs of John Kennedy and fiancee, heiress Colleen Field, 1960

A wedding photo of John Kennedy and Paula Noble, 1964

The Peter Sellers skits: So Little Time and The Trumpet Volunteer

--

Letters from John Kennedy

In the late 1950s indefatigable Christchurch promoter Trevor King corresponded with John Kennedy regularly, offering his services to publicise Tommy Steele in New Zealand, and informing Kennedy about locals acts such as Max Merritt. These letters come courtesy of the Alan Galley Collection.