Eddie Rayner at the June 2014 A Strange Day's Night shows - Photo by Jason Hailes, courtesy of the Play It Strange Trust.

In March 2022, Gareth Shute spoke to Eddie Rayner while researching his AudioCulture profile. The heart of the discussion is Rayner’s long career in music which has spanned a range of bands, including Space Waltz, Split Enz, The Makers, Crowded House, and RBR (a three-piece that includes Brian Ritchie of Violent Femmes, and Michael Barker of Jon Butler Trio). More recently, he has been working with Tim Finn using inspiration from the early Split Enz songs/demos, in a project called Forenzics. The discussion below also covers highlights of Rayner’s career, such as creating the ENZSO performances/albums, and recording with Paul McCartney.

--

You were self-taught, but didn’t start seriously until you were 17?

My mum sent me to the local piano teacher when I was 11 years old … I lasted about three months with her, which left me with a basic knowledge of where the notes were on the keyboard, but I couldn’t play or read music. There was always a piano in our house, and my dad was an amazing piano player, stride-style – but he always used to play behind closed doors. You would hear this incredible piano playing coming from the lounge, but the doors would be closed, and he would stop playing as soon as anybody else dared to walk in. Quite strange. So he never taught me but I guess it was in my DNA.

“I bought a $200 Vox organ on hire purchase from Kingsley-Smith’s music store.”

I was expelled from school at 17, along with acquaintance Steve Hughes, for the crime of wearing our hair a little bit longer than the rules allowed [over the collar]. Never being one to do what I’m told, I was gone, but I was over school anyway. The social thing at school was fun but academia, while I was good at it, was plain tedious for me. Neither Steve nor I had any clue of what we were going to do with the rest of our lives. We went into town, and I bought a $200 Vox organ on hire purchase from Kingsley-Smith’s music store, an identical one Alan Price from The Animals had. We decided to form a band – Steve played bass and sang, and that was the start of it all.

Our first band was called Hungry Dog, and we played covers like ‘Proud Mary’, ‘Hey Joe’, and ‘Listen to the Music’ … those sorts of songs. Paul (Wally) Wilkinson, who lived nearby, became our guitarist, and our friendship has endured to this day. We did a residency on Waiheke Island over that summer and played a few clubs in town. These days, residencies aren’t a thing, but I think they should be resurrected. If you perform once or more a week, you get the chance to hone your chops and you’re going to derive a bunch of skills quickly that are hard to come by any other way.

How did you progress from there?

Initially, I was a bit ambivalent about being a musician because I didn’t like the sound of my Vox organ. I also found playing in a band to be physically unpleasant because of the sheer volume – I found it quite excruciating and uncomfortable. I was coming and going from that band for quite a few months. Probably a year after I started, I decided that I wanted to get serious about playing. I was 18 and my girlfriend and I headed south to Christchurch. I scored a job in a market garden, and we found ourselves a house on the beachfront, in North Beach. We were down there for less than a year, but I bought a piano from a second-hand shop and spent a lot of time outside of work trying to emulate the piano parts in songs that I liked. I often didn’t know who the players were, but I’d hear certain songs on the radio that appealed to me and tried to learn how to play them, by ear. That became my modus operandi and I’ve still never had to learn how to read music. I can read a basic chord chart, but I can’t read sheet music. Haven’t ever needed to ...

But you were ready for more serious working bands after that?

After that year in Christchurch I ended up back in Auckland, living at home again. There was a band called Roger Skinner and The Motivation who were quite legendary at that time, or so I thought. Roger’s still playing to this day, which makes him even more legendary, to me. He advertised in the Herald for a keyboard player and asked me to join after the audition. I thought I’d really hit the big time. That was where I first met Paul (Croth) Crowther, who was the drummer. I think Paul had heard of me around the traps, and we became very good friends. Later we both hooked up with Alastair [Riddell]. The three of us formed an originals band and Wally Wilkinson joined on bass, who soon joined Split Enz (before me), and who was instrumental in my joining the Enz. We called our first originals band Orb and we played mostly our own songs, sprinkled with some obscure covers from overseas. Alastair wrote most of the songs and soon discovered David Bowie. Croth and I were into prog rock. We listened a lot to Yes, Genesis, and Emerson Lake and Palmer, amongst others. I loved the complexity and colours in that style of music.

How did you guys meet Alastair?

Just a grapevine-type hook-up. We were aware of Alastair because we’d seen him playing at the university in a blues band called Original Sun. He’s a very good blues guitarist, and had charisma – we liked his look and the way he sang.

“We found out pretty quickly heartland New Zealand was not into original music.”

Did you mostly just play around Auckland?

We probably played as far south as New Plymouth or Palmerston North. We found out pretty quickly that heartland New Zealand was not into original music and certainly not interested in hearing songs by the more obscure international artists. We were doing originals and some prog songs like ‘Roundabout’ but Yes or Genesis were unheard of in heartland New Zealand. So, we thought, “we’ll have to get back to doing pop covers because we need to support ourselves”. We started a covers band called ‘Stewart and the Belmonts’.

[Eddie pulls out an old poster advertising Stewart and the Belmonts]

This is a poster that was done by Brent Eccles. Here he displays his early talent for promotion. Stewart and the Belmonts quickly scored a residency at the Kawerau Tavern and we stayed there for a couple of months, I think. This was where I learned to interpret a chord chart, because on our first night there, without warning we were called on to “back the floor show”, which was a singer called Enari who, with no prior warning, presented us all with chord charts which none of us could read. Disastrous, but a good way to get the guitar player to turn down.

Otherwise, we just played around, but it was kind of soul destroying and tedious, and to this day, I don’t understand how people can play covers year in, year out. I guess it’s just a mindset, but not mine. Pat Khutze is working with me on a few projects currently. He’s a very well respected, great drummer and band member. He’s been doing covers most of his life and he’s totally over it. He agrees – there’s something so much more satisfying in collaborating/creating and playing your own music. It’s fun playing covers for a short time, but I couldn’t do it for any longer than a couple of weeks.

Is that how you moved on to doing Space Waltz?

Orb morphed into Space Waltz. Stewart and the Belmonts was a parallel band, but I left Orb for some reason. There was no acrimony or anything. Probably just me being fickle. Later, when I’d reconnected with the guys, we decided to start a new band called Space Waltz with a slightly different line-up. Alastair, myself, Peter Cuddihy (bass) and Brent Eccles (drums) remained from the Belmonts, and we asked Greg Clark to join as second guitarist.

Alastair Riddell and Space Waltz. L to R: Brent Eccles, Peter Cuddihy, Alastair Riddell, Greg Clark, Eddie Rayner

Space Waltz had a relatively fast rise to success through New Faces.

It all happened really quickly. I’d already heard from Wally Wilkinson that Split Enz were keen on having me in the band to take over keyboard duties from Tim who wanted to be out front as lead singer, but at that point they were more of a folk/acoustic band and I didn’t really like the sound, so I wasn’t particularly interested. But a year later, once Wally had joined playing electric guitar and the songwriting had developed, their sound somehow appealed to me a lot more. They appeared twice on television, but I think it was when I saw them on New Faces that I decided I wanted in. Even though I was in a band who had a No.1 hit single and we were writing our own material, there was something about Split Enz that I just found magical and appealing. Tim and Phil’s voices together were pretty special and distinctive, and the songs were unique, like nobody else. It was a very difficult decision for me to make, but they did ask me, so I joined, even though I felt quite guilty about leaving Space Waltz.

Space Waltz always came across Alastair’s project, but your keyboard sound was quite central to the band’s sound.

Just an integral part really. Less so than the guitar parts. We recorded the album at EMI in Wellington. We’d been playing the songs live anyway, so we all knew our parts, and just had to go in and record them just as we played them live. Several weeks later, when the album was finished and we saw the album cover, it had somehow morphed into “Space Waltz, by Alastair Riddell” unbeknownst to the rest of us. We all thought it was a bit strange, and to this day, I still don’t really know how it happened – whether Alastair wanted it that way or whether the record company insisted – but that’s what happened.

Was there much room for you to contribute creatively when you first joined Split Enz?

We were all very young and callow, as well as being really excited, enthusiastic, and happy to be in the band. Like puppies. Phil Judd was doing most of the writing. I thought he was an oddball, but artistically gifted. I’d heard him described him as a genius and – even though he was difficult to deal with at times – he would come up with ideas that I’d never imagined before could’ve existed, in terms of chord structures, melodies, and lyrics. I thought they were brilliant.

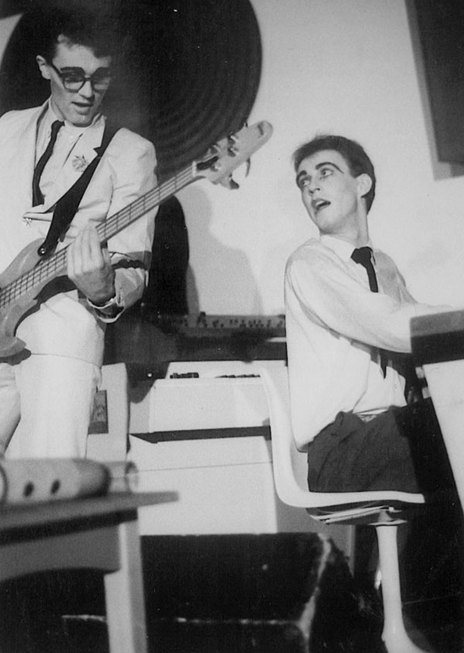

Mike Chunn and Eddie Rayner, 1976. - Photo: Mike Chunn Collection

But it was very much a band. We would all arrive at rehearsal and just start playing, unwittingly and willingly contributing to the overall shape and content of the songs. After all, that’s what a band does, right? A “real” band creates the presentation pack for their original songs, though that largely goes unnoticed on a recording, when one person is often credited with the composition. The presentation pack of the song is a whole bunch of things, including the performance, the parts and arrangement, production, the mixing – the overall sound of it.

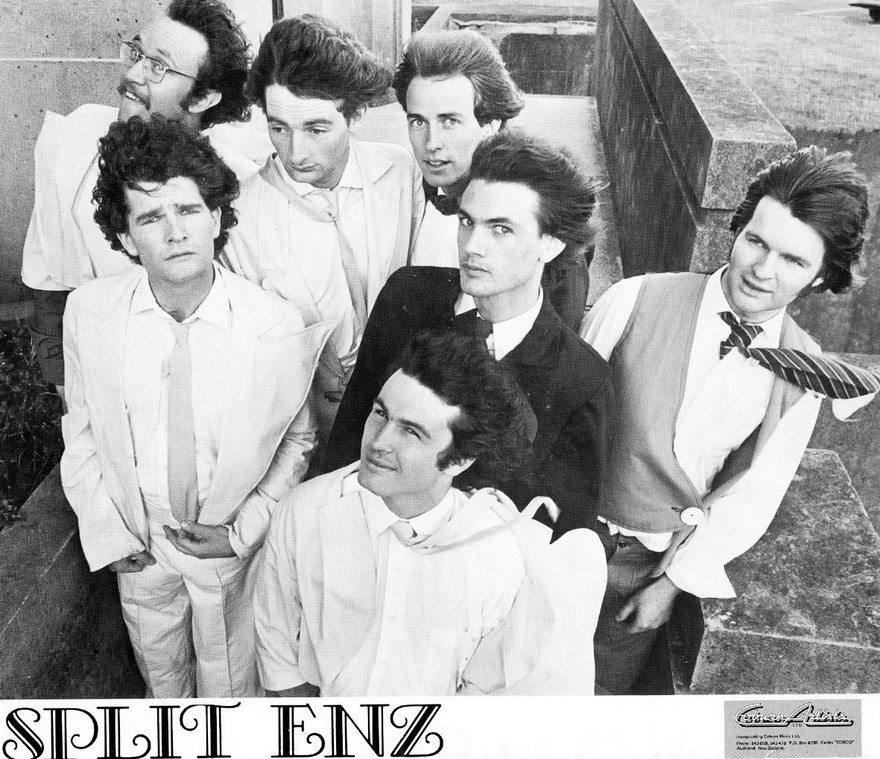

Mental Notes publicity shot, 1975. Back row, from left: Wally Wilkinson, Noel Crombie, Eddie Rayner. Centre: Timothy Finn, Philip Judd, Emlyn Crowther. In front: Jonathan Michael Chunn. These were the names credited on the album. - Simon Grigg Collection

Bands are in large part responsible for that, but they are often unrecognised for the way or style in which a song is completed and presented. They’re seldom, if ever, given even a chord chart, let alone written parts to play and often the component parts and arrangements are actually composed by the band members. Back then we were all contributing and having fun with it, and simply loving what we were doing. We were on a mission because we all believed so much in what we were doing. We recognised the band’s uniqueness, musically and visually. We were determined to strut our stuff on the world stage, to show how great our songs and we were as a performing band. Of course, we probably weren’t that great at that point, but we got there in the end.

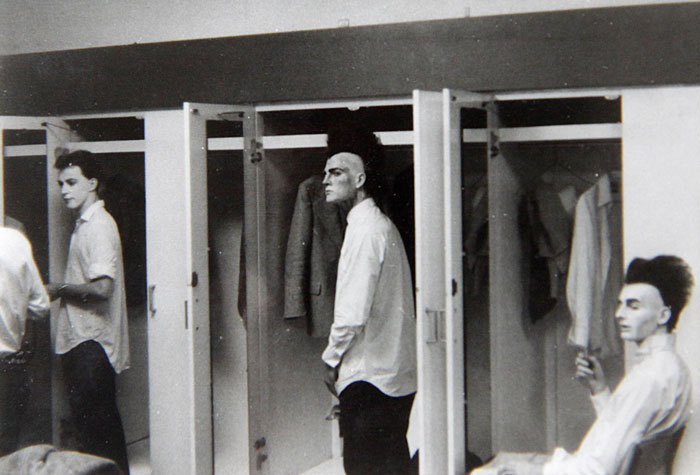

Eddie Rayner, Tim Finn and Noel Crombie, Europe 1976/77. - Mike Chunn Collection

It must have been quite intense. You joined and then you would have played His Majesty’s Theatre quite soon after that in front of 1200 people. Then the band moved to Australia and recorded Mental Notes all within a year? Then on to the UK.

Pretty much. I think I joined in March one year, and we were in Australia by March the next year. It was a mad, eccentric crew of guys. There was Tim, Phil Judd, Noel Crombie, and Robert Gillies, all gifted in their own right. It was a very unusual group of people and a huge wellspring of creativity. It is hard to explain why joining Split Enz was so appealing to me, but that was a huge part of it. Something in me recognised the genius of Judd, I loved Tim’s voice, and I loved the gel of Tim and Phil’s voices together. A very unusual sound, I’d never heard anything like it. Noel and Robert’s visual aesthetic was appealing as well. The fountain of creativity that was emanating from the band was something I relished the opportunity of being involved with. I felt like I’d arrived home.

How did it feel when Phil left? It must have been stressful for the band to come up with new songs without him there.

When Phil left, the songwriting mantle fell on Tim, and he liked the idea of me being his sidekick, helping him out and giving him confidence to finish his own songs off. After the infamous fisticuffs at the end of a difficult American tour in 1977, Phil left, and Tim and I went to stay at his uncle’s place in Baltimore, where we stayed for several weeks, writing and completing songs. We wrote or completed all of the songs on the Dizrythmia album there: ‘Bold As Brass’, ‘Charlie’, ‘Without A Doubt’, ‘My Mistake’.

You can really hear your piano parts on ‘My Mistake’ and ‘Parrot Fashion Love’. Your synth part with the bending notes that start ‘Bold As Brass’ is probably the main hook of the song.

At that point we didn’t have a “proper” guitar player. We’d asked Neil [Finn] to join, and he accepted but he’d never really played electric guitar before. He’d been an acoustic guitar player. We knew he would develop and that he could write cool songs and was a good singer. He seemed like the obvious choice once Mike Chunn suggested him. Our initial reaction was that he wasn’t a genuine electric guitar player, but then we thought he’d make up for it in a lot of other ways and would quickly learn. He arrived in early 1977 and pretty much immediately, was with us at Air London studios. Kate Bush was recording ‘Wuthering Heights’ right next door. Gino Vannelli on the other side, and 10cc were along the corridor. And he was being called on to play all the electric guitar on a Split Enz album! It’s actually not too bad when you listen to it these days, it sounds alright … [laughs]

You did a bit of songwriting yourself. ‘Marooned’ is solely credited to you. Then there were the instrumentals on later albums?

Mainly, I would get inspired through jamming. I understand when the muse is around and when it’s not ... Instrumentals became an integral part of our albums and live repertoire. I don’t know whether the others really liked them, or whether they just felt obliged to give me at least one slot on each album. In hindsight it would have been great if Tim and I had continued writing together back then, but of course at that point Tim was gaining more and more confidence in his own abilities. He became incredibly prolific around 78, when the band wasn’t doing a lot in England, and we were living in different parts of London.

Split Enz, 1977. Back row: Neil Finn, Tim Finn, Nigel Griggs, Eddie Rayner; in front: Malcolm Green, Noel Crombie

Had you started buying different synths in England?

Quite often, I’d read about a new technology, or Paul Crowther might suggest that I check something out. After reading about Simmons drums [the first electronic drum kit using all-electronic sounds], I designed a briefcase-sized version which I thought I could use on stage and visited Dave Simmons’ factory in St Albans. He loved the idea and started manufacturing them, inside actual briefcases. I got the first unit ever made.

Paul Crowther encouraged me to buy a Prophet-5 when they first came out, because they had presets for the first time in history. You could spend hours making up a sound which you could save for later recall on stage. Prior to the advent of presets, I’d be playing away onstage while at the same time thinking ahead about the next sound and programming it simultaneously, using the control panel on a synth. So, onstage I’d constantly be in a state of thinking ahead, and I used to feel somewhat detached from the performance because I’d be so much in my own head, you know? All synths subsequently had presets, and it was a huge positive for my onstage performance. Freed me up to actually notice and play to the audience!

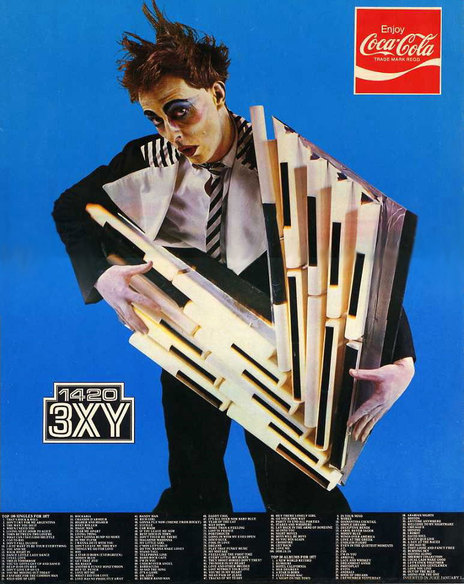

Eddie Rayner in a radio station ad - Simon Grigg Collection

When would you come up with particular synth sounds for each song?

I used to muck around with my synths all over the place: in hotels; in the tour bus with a set of headphones; very often in rehearsal rooms and soundchecks. In the studio, you get to know what sounds work, because you’re regularly getting to hear them back inside the forest of guitars, drums, and vocals. So a lot of the sounds that I tried to use in the very early days, I wouldn’t use now because I’d learned – “no, that’s not going to work inside this particular song, because the harmonic content isn’t right or the feeling of that sound isn’t right for the song”. I’m a lot quicker these days at coming up with sounds that I think are appropriate for a particular set of lyrics and will fit well with the backing track.

Another early instrumental of yours on a Split Enz album was ‘Double Happy’ off True Colours. How did you go about creating them?

I’d just jam them in the moment, when I felt inspired. More often than not, it would just be myself, or me, Mal Green and Nigel Griggs jamming together. Generally the songwriters were off doing their own thing. Back then, there was never any inclination to work on them much as a band or turn them into songs with lyrics because they were always simply regarded as “Ed’s instrumentals”.

It’s interesting listening to some of those instrumentals now. Some of them are quite epic. ‘Albert of India’ in particular has quite a few changes in tone and a lot of different synth sounds. It must’ve been hard to piece it together to play live.

Live it was easy because I just played solo piano all the way, with a bit of synth here and there. On a recording, you can add endless layers to a song. You haven’t got a hope of recreating it perfectly on stage, without a computer synched up – you’ve only got two hands, after all. But playing along with a laptop has never appealed to me. Every time I perform live, I like to play everything as a complete performance. So I cherry-pick the important bits and sounds that I know people would like to hear and leave all the other bits and pieces that you might have used in a recording, to the imagination of the listeners. They’ll hear it in their heads anyway. As long as the most important pieces are there in the performance, that’s all that really matters.

How did you get into production in the 80s? The most striking one for New Zealand audiences is probably the Pop Mechanix song ‘Jumping Out A Window’ which reached No.21 on the charts.

I think that was my first production. I had always been drawn towards production because – out of everybody in the Enz – I was usually the guy who stayed up till five o’clock in the morning alongside the producer, mixing or overdubbing. Often it was me and David Tickle or me and Hugh Padgham. I’m interested in the creation of records, how all the component parts work together. I still get excited and compelled by good arrangements. I love how they work, how layers of sound work together. It’s just something that’s part of me. So production and arrangement became a natural path for me to head into. Today I’m still doing exactly the same thing I was doing back in 1980, except now I’m doing it with a lot more confidence and expertise.

“I still get excited and compelled by good arrangements. I love how they work, how layers of sound work together.”

You also worked with a lot of Australian acts – for instance The Promise and Russell Morris. You also played almost all of the keyboards (bar one song) on the album Howling by The Angels, which included your old bandmate Brent Eccles on drums.

Ahh – ‘We Gotta Get Outta This Place’. It took me right back to The Animals and Hungry Dog. The Alan Price/Eddie Rayner Vox organ … but Alan always made his Vox sound good. Yeah, I played with or produced heaps of Aussie bands and solo artists.

The album was a massive hit and went to No.6 in Australia and No.10 here.

It was fun, really enjoyable. I’d befriended the producer, Julian Mendlesohn on another production he did, and he asked me to do the keyboard parts on The Howling. I toured with The Angels later to promote the album, but had to bail after several gigs because I couldn’t hack the onstage volume and all the shenanigans!

So you were doing a lot of stuff over in Australia that people in New Zealand probably weren’t even aware of?

Oh yeah, I guess. I’ve worked with Tommy Emmanuel, Joe Camilleri, Ross Wilson, Russell Morris, Goanna, and heaps of others. There’s so much psychology involved in production, especially with lead singers I find, who often seem to have insecurities masked by arrogance and ego. Forget the musical stuff, it’s the people-management that’s most important!

You did the Paul McCartney sessions for his 1986 album, Press To Play. It must have been quite surreal?

Yes, I was working with Paul for about three weeks. I remember at one point I gave him a whole bunch of demos that I’d done with Neil Finn in my lounge in Melbourne. Paul played the cassette a lot in his car to-and-from the recording sessions. He loved ‘Message To My Girl’ and really admired Neil’s songwriting. Paul’s pretty much the same guy in the flesh as he is when you see him being interviewed. He is very down to earth, affable and a lovely person. Very generous.

But I’ve heard you say that there wasn’t much creatively for you to be able to input in that session?

To be honest, I’d been working with Crowded House and in my opinion Neil was peaking in his songwriting. All of these amazing songs like ‘World Where You Live’, ‘When You Come’, ‘Better Be Home Soon’, and ‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’. I thought the McCartney album I did paled in comparison when it came to song quality, but the actual experience was truly amazing. To be playing with that calibre of musician – Phil Collins on drums, Carlos Alomar and Pete Townshend on guitars – was unbelievable. How quickly they learnt the songs. We’d have versions done within a few minutes.

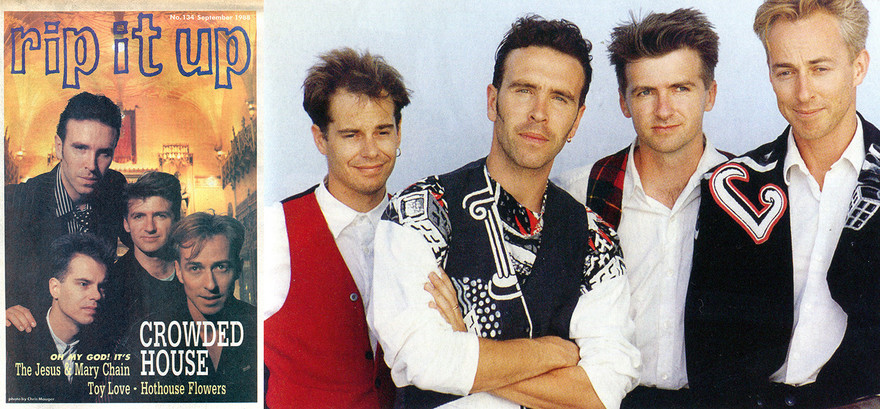

Crowded House featured in Rip It Up #134, September 1988. At right: Paul Hester, Nick Seymour, Neil Finn, Eddie Rayner. - Photo by Kerry Brown

Your involvement with Crowded House was a funny thing because you were there from the inception, but you became more of a live musician with them.

I only ever wanted to be a sideman in the band. I was doing my own thing at that time with a friend, Brian Baker, in a duo-band called The Makers. We were signed up to East West, a sub label of Warners in Sydney. The guy who signed us up was the managing director of Warners, Philip Mortlock, who’s now working on the Forenzics project with Tim and me. But at the time when Crowded House was starting to fly, Brian and I had signed a deal with Warners which was a commitment for two albums, which I wanted to see through.

“Crowded House would walk into the offices of its record label, Capitol Records in LA, and everyone would stand up and clap.”

Neil asked me to join Crowded House then, because I’d been playing with them for a couple of years on and off as a session and “live” musician. I told Neil I could join the following year, but I had The Makers commitment to fulfil first. I was meant to join Crowded House for a Canadian Tour [in 1988] but then my dad got really sick and I had to come back to New Zealand to take care of all that. Neil asked Mark Hart to deputise for me and in the end they offered him the job. I couldn’t do anything about that and I was quite happy with that decision at the time too. But it was really quite enlightening touring in America with a No.2 hit single ‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’. People celebrate and applaud success in the States, it’s different here.

They’d treat you nicely rather than telling you not to get too big for your boots?

Yeah, we’d walk into the offices of our record label, Capitol Records in LA, and everyone would stand up and clap. They’re celebrating our and their team’s success, you know? It wouldn’t happen here.

You were still living in Australia and playing in The Makers?

Just prior to The Makers, there was the Schnell Fenster thing. I asked Phil Judd if he wanted to get together and write some songs. We wrote a whole bunch of stuff really, really quickly. We asked Noel Crombie and Nigel Griggs from Split Enz to join, as well as the brilliant Michael den Elzen as a second guitar player. But soon, I decided that I wouldn’t carry on with it. Phil Judd has undeniable talent, he’s a genius, but we didn’t gel professionally. I’ll leave it at that.

Anyway, The Makers superseded all that. We went on to do two records and had a minor hit in Australia with the songs ‘Big Picture’ and [its] follow-up ‘New Kind of Blue’. But I never really felt totally comfortable with any of it. I’d been in a great band for 12 years already and I was playing in Crowded House simultaneously. I had just started a family, was getting offers for production, and I was going off and touring.

I guess, after having been in a band such as the Enz for 12 years, The Makers seemed somehow “less”, even though I was really proud of our achievements and the material, it just wasn’t in the same league. Crowded House was lean and tight – a minimal and perfect band. I just loved playing those early songs as well. Neil has written plenty of other great stuff subsequently, but there was such an outpouring of amazingly appealing songs from him at that point in time … and The Makers’ songs, while still good, weren’t in the same realm as Neil’s at that point in time.

We were writing some high-quality material, but there were only two of us in the band: myself and Brian, plus live sideman Michael Barker. Michael is a virtuoso drummer and percussionist. He can play anything – keyboards, guitar, sing. He’s über-talented and clever as hell. But I think it was the fact that I was playing bass on the keyboard, doing the keyboard parts and singing at the same time that spoiled my live experience in the Makers. We should have gotten a proper bass player, but we decided on a very compact, three-piece electro-pop band. And I just didn’t like it much. So after the second album, I left The Makers, and moved back to New Zealand.

But over the years you’ve brought Brian in for different projects, so you’ve stayed in good contact with him.

Brian and I are very good friends. We work together semi-regularly to this day. He’s moved back to New Zealand and lives south of Whāngarei. He’s out in the country north of Auckland, has embedded himself in the community, doing his own thing and living off the land. He sends material to me, and I add my bits and pieces, and vice versa, we’ve worked like this for years.

It must have been hard going back to New Zealand when you had so much going on in Australia?

I came back in 1994, Split Enz left New Zealand in 75. So it had been nearly twenty years. It was a conscious decision to come home because I had a couple of kids by then. I had my first boy when I was 33, in 1985. I’d never really thought about coming back to live in New Zealand up till then. New Zealand was always my home, but it did feel like a backwater for most of those twenty years. In the early 90s, something changed in New Zealand and suddenly you could get a good coffee here (laughs). It had a much more positive upbeat vibe than I’d felt in the years since I’d left. That’s when we decided to come back.

ENZSO was another big thing that you did in the 90s. I heard that you just went to orchestral concerts and worked out where the different instruments sat?

I didn’t do a lot of that; I might have gone to one or two orchestral concerts. But when I launched into ENZSO, I didn’t really have any idea about the orchestral machine, to be frank.

It was extremely ambitious for someone who doesn’t read music.

I would have foolishly thought “how hard can it be?”

How did you approach it?

I did really cool-sounding demos on my computer and keyboard. To me they sounded like what an orchestra should sound like, albeit synthetic. The demos had something about them that led me to believe that they were reasonably authentic and that if the NZSO played the sheet music, then it would sound similar, only better – but of course it didn’t. The symphony orchestra is a huge, lumbering, amorphous mass, and a quite unwieldy beast. Not that I was wielding it, that was in the hands of the conductor.

Neil Finn taking a break from the mic at the 1996 ENZSO gig in Auckland - Dave Dobbyn, Neil Finn, Annie Crummer, Tim Finn

I loved the sound of the NZSO, but the thing that I found hard to cope with, was its “feel”. A drummer like Paul Hester for instance, had his own feel and whenever he sat at the drums and played, everybody knew, it just felt good. But it’s hard to describe or analyse feel. The orchestra is a huge body of players, all with different personal musical aesthetics – how do you articulate on a score “must feel good”? The thing that perturbed me most, was what I called the “lag”. The “downbeat” in popular music is so important, but orchestrally not so much, so I was feeling that the orchestral versions all lumbered and staggered along, when my synthetic versions all got along at a good clip, so to speak.

We toured the entire NZSO, National Youth Choir and singers here in New Zealand, and used different orchestras and choirs in Australia. In the end, I was trying to dictate the feel I wanted for each song with my piano parts. Normally the conductor would be responsible for the whole thing, but in the end I felt that if I played loud enough then the band would get the vibe.

Let’s jump forward a bit now to the project you did with Brian Ritchie from Violent Femmes and Michael Barker from Jon Butler Trio. How did you meet them?

Michael Barker was in The Makers’ live band. He played in the Jon Butler trio for years but now lives back in his hometown, Rotorua. He came back after Jon Butler decided to change his band’s line-up, God knows why. Michael mentioned to me that he’d met Brian Ritchie so we just organised a jam. Brian came over from Tasmania where he lives, we went down to Roundhead and improvised twenty pieces in a few hours. I edited and finished them up at home on my computer. Later we did another session at Michael’s studio in Rotorua. We wound up with a bunch of cool material which I completed and mixed at home. We farmed it off to a music sync/licensing company, but they’ve done nothing with it, of course. So it’s just lying around in a vault somewhere.

In some ways, it was getting back to what you did in Split Enz – writing stuff in the band room?

That’s right. I had in my head little chord sequences that I’d start playing and they’d just join in. Then we’d jam around that and turn it into a piece of music. That approach has become my thing. Split Enz did a lot of that as well, particularly in the rehearsal rooms. There was loads of jamming going on, and a lot of dope being smoked. Not by me, of course [laughs]. Nigel Griggs would bring along a cassette player and later he’d spend hours and hours editing the good bits onto another cassette player. Some of those bits became parts for Enz songs.

It must have been a nightmare to work out how you’d got a particular synth part after the fact?

That’s exactly right! I realised from the Split Enz experience more than anything else that something magical happens when you get a bunch of people in a room who are positive, excited, and there to create something together. When you want to make something happen, you can just start playing. In fact, that’s how a lot of the Forenzics stuff started. I’ve got a jamming band called Double Life. It’s Pat Kuhtze who is my drummer mate, Adrian Stuckey who’s a dead-set but unheralded genius in many ways, and Mark Dennison who plays sax, flute, and clarinet. He played brass on the first Makers album in Australia, and that’s where we originally met. It’s funny all the ways it ties up. He is Australian but he married a Kiwi girl and moved over here. He’s Mr. Efficiency, very, very talented, and being a university-trained musician and musical director, he really knows his stuff.

I asked them all around to my studio and said “we’re just going to play”. They all looked at me blankly. Like, “play what?” We only did three sessions, a couple of hours at a time, but we wound up with eighteen instrumentals – finished, properly recorded and mixed. I sent those instrumentals off to a few songwriter/lyricists, Tim Finn being one of them, the idea being that they could serve as good backing tracks for songs, as well as instrumentals in their own right. Tim said he didn’t normally do that sort of thing, but a year later, he emailed to say he actually really liked the instrumentals and had written a whole bunch of lyrics for them. Those songs eventually comprised fifty percent of the Forenzics album.

A couple of other people have written lyrics to those instrumentals as well. That’s how Andrew McLennan and I reconnected. He had a whole bunch of songs of his own, so the two of us have made an album as well, called Another Life, which is also the name of our band. Pat Kuhtze is our drummer, though he didn’t drum on the record. I did all the music, Andrew did all the singing, Pat did all the B/Vs ...

Over the years, you’ve had projects that have fed back into Split Enz in different ways. ENZSO and Forenzics being two prime examples. On the one hand, it’s your legacy to draw from. On the other hand, some fans probably think Split Enz should be held reverentially in amber and left alone. How do you approach it?

Just be careful about what you’re doing and think it through. For instance, I’ve never touched the Mental Notes album, even though I have remixed Frenzy, Waiata, and True Colours. There are others that I haven’t touched not because I don’t want to, but because the original tapes have disappeared. But I haven’t touched Mental Notes because I know it would upset a lot of people. Paul Crowther has threatened me with physical bodily harm if I touch it! He loves his drum sound on the existing mixes, and that’s fine. I (probably) won’t touch it. People love it, that’s the way it is. I could make it sound much better though [laughs].

When it comes to doing what we’re doing with Forenzics and using snippets or samples from old Split Enz songs and creating new songs out of them – I simply ran it past everybody in the band, those who I thought might be interested. Phil Judd had okayed us using bits and pieces, and I’ve told Wally, Mike Chunn, Geoff Chunn, Mal Green, Paul Crowther, and Neil. They’re all fine with it. I think once they hear it, they’re all okay with it, you know? You get the occasional cynical trainspotter who says “just leave the bloody thing alone, what are you doing mucking around with the old stuff when you could be doing new stuff?” Well excuse me, it’s brand new stuff. It’s just utilising some of the old stuff as a place to start. And, we’re also doing totally new material!

It must be satisfying when you get a chance to go back down the path not taken and work with old friends. That sentiment could also be applied to the fact that you did end up recording some keyboard parts for Crowded House’s last album that they did at Karekare.

Yeah, I did a bit on that and we’ve remained friends. It’s not like we live in each other’s back pocket or anything like that, but there’s certainly no acrimony between any of us. I don’t think there really ever was. There was a bit of angst between Tim and Phil for a while, but we’ve all grown up now. It’d be nice to think that we could all actually get together around a table and just laugh, reminisce and talk about stuff, anything. But some people are more tormented by that history than others.

Myself, I feel at peace around Split Enz, because I’m reconciled to the huge part of me that it still comprises. I look after all the surviving tapes and still have loads of memorabilia. I don’t know all the stats, I’m not like the fan club guy, but I know where everything is, and it’s precious to me.

Space Waltz, 2022. From left: Brent Eccles, Peter Cuddihy, Greg Clark, Alastair Riddell, Eddie Rayner. - Publicity photo

The same goes for Space Waltz? You’re good enough friends that you can get together and record an album.

We’ve remained friends. There was a wee bit of discomfort around the time that I left, but I didn’t feel it because I was so excited about being in Split Enz, but we’re all good friends now.

How did you approach recording the new Space Waltz album?

It’s been a bit of a trial in that it’s taken seven years to complete. We recorded it over three days at Roundhead Studios in 2014 and I’ve only just recently had all of the parts delivered to me for the mixdown. But now it’s finished, it’s fantastic and it’s coming out very soon. There’s a single out now getting good radio play, called ‘Hypnotize Me’.

Well that’s just another sign of the widely varying nature of your career. You can do an album with Brian and Michael in a weekend, but another album might take seven years.

Yeah, that’s totally correct. Different people work in different ways, and it’s very much an exercise in dealing with human foibles and relationships. Me, I just like to work, get things done, and have fun on the way!