Damien Wilkins in 2024. - Ebony Lamb

Damien Wilkins is the author of 14 books, including the novel Delirious (2024), which won the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the 2025 Ockham NZ Book Awards. As a musician and songwriter, he writes and records as The Close Readers, whose album Trees of Lower Hutt was released in December 2025, The Lines Are Open in 2014, and Group Hug in 2011. In the 1980s he was a member of Wellington band The Jonahs. The Lines Are Open made it on to the 2015 Dean’s List: the year's best records, compiled by influential US critic Robert Christgau. “His tune sense will sneak up on you,” wrote Christgau, “and two of his catchiest songs are about novelists.”

--

Dave Dobbyn – Language

I saw Th’ Dudes live as a teenager and was taken aback when the frontman stepped away and the guy off to the side came forward to sing their hit. Then a few years later we broke into Wellington’s State Opera House and danced ironically to DD Smash in the closed-off upper level. We could be very obnoxious but we also loved ‘Whaling’.

Dave Dobbyn - Twist (Epic, 1995)

The album Twist from 1994 is Dave Dobbyn all grown up and suffering adult themes and some heavy self-consciousness: “My heart from a gun / Now it’s caked to the walls / It’s performance art / And it’s framed by a house.” The production was self-conscious too. It was an extension of the echoey sound world of the previous year’s Lament for the Numb, where Elvis Costello’s rhythm section is placed a million miles away. This is the lonely Dave period, downer Dave. Even the drummer and bass player aren’t hanging out with him. The breezy confection of ‘Outlook for Thursday’ happened in another universe. The damaged singer came home after LA’s Lament to make Twist, as in a knife not the dance. He’s really not thinking about dancing. Rather it’s doubt, hesitation, fear, shame, guilt, excess – useful muses for a Catholic boy who knew he made no sense as a pop star or rock persona but who had a gift for hooks.

In interviews from the time Dobbyn talks about reading Janet Frame and Pablo Neruda. Lyric poetry not lyrics. “It’s all atmosphere!” he laughs in another interview. That laugh. He never speaks without it. He takes to seriousness like it’s tickling – he can’t tolerate it for long. Amid all the dark and the emotionalism and the poetry, he’s still Dave Dobbyn and the radiant songcraft keeps breaking through. On Twist, the more trad quiet ones (‘It Dawned on Me’, ‘I Can’t Change my Name’) are the songs I still want to listen to. And ‘Language’ of course, which continues to hold its own in a stunningly large repertoire.

It’s a piercingly articulate song about someone who can’t say what they mean to the person who means most to them. Here, let me tell you what I can’t tell you. Dobbyn has always known how to access pop’s secret power to share some abject state while consoling us with sound. I especially like the moment before the guitar takes over in the middle of the song: “One day a heap on the ground / Next day I’m so proud / Today – I don’t know, I don’t know.”

That great pause after “today” and then the repeated statement of loss (‘I don’t know, I don’t know”) falls into the space because … language don’t work no more.

Maybe the masterstroke here is that Dobbyn settled on the word “language” as the thing he can’t find rather than the narrower and more conventional “words”. Language is fancier of course and the whole record embraces pretension but here it’s majestically worth it. This damaged couple needs a translator not a thesaurus. Or maybe they just need to break up. All that gun-scattered heart caked on the walls is hell to clean off.

The Clean – Anything Could Happen

It’s a minor mystery that The Clean never really did much with lyrics after Boodle Boodle Boodle. Why didn’t they continue telling funny, touching stories? Maybe their sporadic reunion records made jamming the quickest route to song and words became afterthoughts. Whatever message they had could be carried in the trio’s magical bondedness, two brothers and a third near-sibling, forever in-step on alt rock stages around the globe. I’m not here to begrudge them an iota of whatever fun they had and gave. It was plenty. But for now I’m thinking of words and even in most of David Kilgour’s solo stuff the words are largely placeholders that were never upgraded. (Honorable exception: the infinitely playable Here Come the Cars.) Did Robert Scott walk off with all the narrative? Actual singing could become fairly perfunctory, which was a loss.

The Clean - Boodle Boodle Boodle (Flying Nun, 1981)

Anyway, this one is instantly alive from its first acoustic strum, and the words really help, as does the commited vocal. “Went to a doctor said I looked so hard and with a smile on his face pointed me to a junkyard / Looked for an answer in empty doorways, talked to a dancer said it’s out on the highways / Well c’mon doctor won’t you gimme a shot, I’m feelin cold boy I’m feelin hot / Doctor said no boy you’ve gotta learn / first I’ll shoot up and then it’s your turn.” Later verse: “Begged for consolation and I got none / I haven’t the motivation to get myself a gun.” You’d probably have to wait until the arrival of New Zealand hip hop to find an internal rhyme with the cleverness of “consolation” and “motivation”.

The Dylanish speaker, self-aware in his self-mythologising, is depressed (“Well here I am in the big city / I got no heart and I got no pity / Can’t you see I’m on the run? / Can’t you see I’m not having any fun?”) but the music puts something irresistible in the air and the chorus swamps his negativity. Everything seems possible! Anything can happen! And for a few years it did.

The Clean came to my town in the early 1980s and immediately cut through the death-haunted Anglo gloom of much of Wellington’s indie scene. I remember seeing them upstairs at a Courtenay Place bar one afternoon and again playing in the daytime at Auckland’s Rumba Bar, when we followed them up the island, enraptured. The light came out; it seemed to be attached to their paisley shirts. People smiled and bopped around. With Shoes This High at the Rock Theatre, we all seemed down a dark wet well and all our clothes – jerseys and long coats – were rotting. Post-punk words were hard to catch, which was a blessing. My own beloved The Gordons used their mics to shout paranoid stuff about taking your tablets, “every four hours”. That seemed alarming and a bit silly. David Kilgour’s visit to the doctor was so much funnier and more human.

If The Gordons had written a song called ‘Point that Thing Somewhere Else’, we all would have experienced the anguish and retreated into the shadows feeling satisfactorily punished. But The Clean, uncertain in love (“Baby when you say you want me / I’ll faint and know it’s not true”) seemed oddly and winningly free of anguish. Yeah, point that thing over here, we like it! We might even faint. And how strange that verb “to faint” is – how far from male vengefulness. The love object is wrestling with its own vulnerability. “Don’t point me out in a crowd” – as if being noticed was the beginning of the end. That absence of declarative certainty was in The Clean’s personal affect and in its Velvety humming grooves. Previously our own awkwardness could only see itself in angularity and extreme loudness but this corner of the “Dunedin sound”, which we were all ready to meet with scorn, turned us towards other friendlier options involving tunefulness and sunlight.

Chris Knox – Becoming Something Other

“And the CAT scan showed his brain was losing mass

And he didn’t know each morning where he was or how he’d come to this impasse.”

In the days of Toy Love, this scenario might have slipped easily into their brand of cartoon horror. It would have been fun – brains shrinking, yee ha! Now the singer is playing for keeps. His father has dementia and terrifyingly understands what’s to come:

“I asked my dad, how much his vision was impaired

He said he sees things, but that the things he sees were things that are not there

Then he paused and quietly spoke this words that chilled

‘I have my own small thoughts about that’

And I felt the air around me grow quite still”

Chris Knox's Beat album, released by Flying Nun in 2000.

The father’s devastating line – so characteristic of him, we feel, even though we don’t know him – is one of those moments where suddenly we hear a song break free of the singer’s control and the other person speaks. In speaking, the father takes back control, or whatever is left of it, and reinstates the concept of privacy which the song, the son, is threatening to take away. The father’s “small thoughts” are the unshareable feelings the singer is trying to understand. Of course he can’t. Stuck, he can only cry softly and then repeat the words of his mother’s phone call – someone else’s voice, also at a loss to state the exact dimensions of the awful thing that is happening. The entry of the consoling piano is one of the most agonising things in our pop music.

Chris Knox’s vast musical catalogue – is it vast? – awaits me. Can someone do a Best-Of? Back in the day I dutifully bought the first couple of Tall Dwarfs EPs, though I hated the bad joke of the name and mourned the absence of Paul Kean’s great bouncy bass in Toy Love. I found the DIY approach a bit wearying. There’s only so much dinky keyboard I can take. Why was he throwing away his talent? Like, wouldn’t it all be better with an actual drummer? Hats off to the man though. He did it his way. Some of the solo gigs I saw him play, which could be in the most inhospitable settings, were bad and some were heroic.

Bravery is hard to turn away from. ‘Becoming Something Other’ is about bravery too – that of the singer’s parents. I doubt that Chris Knox would think he was being brave for writing so candidly about this pain. The complete absence of the slightest whiff of self-congratulation makes us credit the songwriter with the very thing he denies himself: the idea he too has the courage to face this. It’s a miracle of storytelling that in the recounting of these domestic scenes of phone calls home, the great wildman of New Zealand punk ends up closer to the delicate manners of his dad.

Aldous Harding – Treasure

It all clicked for me when I saw Aldous Harding at the Michael Fowler Centre in the days before the first Covid lockdown. A bloke beside us let out a huge sneeze which we felt on our cheeks and when he didn’t come back to his seat after the intermission we thought we were going to die. Instead we listened and watched Harding and her oddly atomised and expert band deliver her disjunctive songs, which was utterly mesmerising. They put the songs together with a kind of fastidiousness I’d never seen at a gig before. I don’t mean it was cautious and perfect in the sometimes painful way folk concerts can proceed – let’s all not breathe during the next Dobro solo. It was goofy and sometimes hard to follow. But we all followed. Harding seemed at times surprised that we were there. There was a period when it felt like the soundcheck. She might just be a terrific comedian too.

Aldous Harding - Designer (Flying Nun, 4AD, 2019)

‘Treasure’ is stunningly beautiful. Austere and warm at the same time. Even though it’s mainly a single voice, plucked acoustic guitar and later a piano, the song makes me think of Brian Wilson in the way it continues to find these surprising melodic turns. Harding’s phrasing is astonishing. Is she a wonderful mimic? Her voice can live in many registers and here is her fascinating take on that: “For me, taking identity too seriously is really detrimental to my music. People say to me, ‘Why don’t you use your real voice?’ But what people don’t understand is that I don’t know what my normal voice is anymore.”

Ordinary ideas about confessional songwriting are out and while I don’t think her music is supposed to be “hilarious”, or only hilarious, I also suspect earnestness is more wrong. Was that what put me off at first – the fumes of a cult? Turns out her upending of folk’s problematic emphasis on authenticity is another reason to listen hard. In place of the single female artiste, Harding presents a revolving cast of personae. It’s her solution to this: “… the last thing I wanna do is pay $45 and see a bunch of musicians play their instruments for an hour and a half. [laughs]”

She’s not a musician, she says, but “a song actor”. I have no idea what the actor’s words mean but Harding delivers them with utter conviction while appearing curious herself as to their import. The speaker is in the Amazon with a rock in her hand? The mirror is a worry, given the rock. I could probably read an essay on the song as imaging some colonial action – “I’ve come for your treasure”. Aldous Harding might just shrug, pull a face.

In the Pitchfork interview quoted above, when asked about her cryptic lyrics, Harding says, “I just want everyone to feel like a philosopher.” Yet of all the songs on my list, hers is the one I feel I can do least with. Maybe that’s my issue. She might also be the most entertaining interviewee about songwriting on my list. Here she is again describing the problem of reconstructing the creative process: “I feel like I’m being interviewed about a robbery, and I didn’t see their face and I wanna help, but I don’t really remember how it felt.”

I also love this on perfectionism: “I’ve never written a letter in my life because I always used to screw them up and throw them in the bin. I never sent people letters or mail because the pressure was too much.”

Aldous Harding. - Photo by Ebony Lamb

Harding talks of writing ‘Treasure’ in complete silence, “like coaxing an animal, like holding a piece of bread in my hand for ages until the duck or the hedgehog or whatever had enough space to come and take it from me.” The interviewer presses for more. Harding: “… I sometimes feel like I’m a kid and I’ve been hearing these noises and I’m like, ‘Ghost! Show yourself!’ It’s like this weird, unnecessary therapy where you’re like, ‘Tell me what’s wrong with me.’ You let it come in, you gain its trust, you get all the information, and then you work.” Songwriting as unnecessary therapy – that’s so good. Finally she cracks, asking her own question of the interviewer: “Wasn’t that just the worst conversation you’ve ever had?!”

I confess the lyrical opacity in her catalogue can cause my attention to wander a bit. But certainly not for the duration of this glory. Those ducks and hedgehogs really showed up.

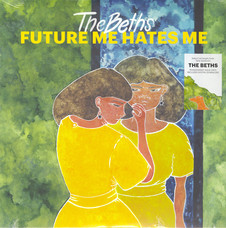

The Beths – Future Me Hates Me

I saw them live at a packed Massey Uni (Wellington) in the Great Hall after they’d come home from their last big international tour and they seemed a bit “Here’s the show and now we’re going to collapse.” But then I saw them on my computer on Neil Finn’s livestreamed Infinity Sessions, before their current world tour, and they were reignited by the new material.

I like the new album but I’m choosing ‘Future Me Hates Me’ from 2018 since it wraps up most of their considerable appeal and skill in a powerful, hooky single package. As a songwriter, the head Beth is not static or trapped, though the delicacy and impact of the song for her mother might suggest a future solo project. As a human she’s facing the kind of health struggles we all hope to avoid. More bravery.

The Beths (from left): Jonathan Pearce, Ben Sinclair, Liz Stokes, Tristan Deck, and Ben Sinclair. - Amanda Cheng

Rather than deployed to state finished feelings, concluded events, words here are what you use to work something out, some puzzle or an internal argument, an emotional obstacle the song just might help its composer with. And as with the music, the lyrics are meticulous and considered. They have timing, like jokes, and semi-punchlines.

‘Future Me Hates Me’ opens with a classic pop proposition: “I never wanted to, I didn’t want to fall/I don’t believe that love’s a good idea at all.” The self is as much a source of confusion as in an Aldous Harding song but The Beths don’t do poetic alienation; they do helpfulness. They propose friendship, decency, the benefits of risking openness. The bright music is an ally not an antagonist. I’m particularly fond of the chorus where the rhyming and linguistic rhythmical chops really shine:

“Future heartbreak, future headaches

Wide eyed nights late, lying awake

With future cold shakes from stupid mistakes

Future me hates me for, hates me for”

You hear that and wonder at how under-explored verbal life is in most songs. Do songwriters not hear what secrets lie in patterning syllables, making them click and strike? That’s the deal right there in four perfectly scored lines. A thoughtful and funny person wrote that; it’s a mind in action.

The Beths' debut album, Future Me Hates Me, released in 2018 by Carpark Records.

You sense the three men are fully on-board with the boss. Of course the blokes can play their instruments very well – everyone can these days – but more than that, they must also be a little in awe of Elizabeth Stokes. You see that too. She is not in awe of herself but in this marriage, they took her name. It’s moving to see a band like this, where care is on show, not only in the skilled coordination of each musical moment but in how they express feeling for each other as people when they play together.

How to explain this? Jonathan Pearce’s guitar can dial in the history of rock and roll in bursts of 10 or 20 seconds, dovetailing with Elizabeth Stokes’s playing and singing, as the music is able to stop and re-start on a dime. His terrific solo on that other jewel ‘Jump Rope Gazers’, in many ways a restatement of ‘Future Me Hates Me’s theme of romantic doubt, might be the best example of care and companionship. It’s such an unexpected part, almost suggesting a mistake. The song, like the relationship it delineates, is crumbling in front of us. Stokes’s flattened singing, as always, does its low to high thing but isn’t about soulfulness. The guitar solo’s odd expressiveness assists her. It becomes the singer, semi-stopped in her tracks, and with that brokenness acknowledged, the song can lift again; the voice can come back renewed: “I think I love you / I wanna give it my best try”. That’s the spirit. Anything can happen.

Sidenote: When I was their age, no one like them could play their instruments with this sort of technical panache and make imaginative rock and roll. Now everyone has been to jazz school and had a creative crisis resulting in the purchase of a Goldtop Les Paul and a copy of Marquee Moon. Sometimes this crosses over into good songs. Past Me Hates Me.

The Mutton Birds – While You Sleep

Okay, some people could play their instruments and make imaginative rock and roll.

The opening image is of someone sleeping “coiled up like a spring”, which doesn’t sound very comfortable. It turns out that the lyrics are also coiled. Here’s the magnificent last verse, written as tightly as you like:

“They will keep

Whatever plans I’ve made

They’ll wait for another day

When I will tell you things that now I only tell you while you sleep”

That last line, with its deft capture of two time periods, is probably my favourite single line in all of our weird little nation’s music.

The Mutton Birds: Ross Burge, Don McGlashan, Alan Gregg, David Long

Watching someone sleep is a strange sort of gift. Are they consenting? We check on children when they’re sleeping. We don’t want to wake our older people. We don’t like to stare. What’s the story here? I think it’s this: the singer is only able to apprehend the love object while it’s stationary. Can only truly cope when things are still. For the bulk of the song, the singer/lover details how unbounded that person is awake (“You looked so hungry / You couldn’t stand still / You made everything in the flat look so cheap”), how magnetic (“You took the room / And pretty soon I knew / That we all would fly to you like little arrows”).

So at one point, this flatmate (?), desired by many (the little arrows), becomes the singer’s own domain. It’s unclear how the singer achieved their cherished status as the one who gets to watch the hungry, active, attractive-to-everyone person asleep or how long it’s all going to last. But this song is a cry of pleasure and pride, unworried by a concept as insignificant as the future. The immediate past (time of the plastic sandals and jumping the motorway fence) is the guarantee of the fabulous present. Planetary motion (“The Earth revolves in space”) is mere backdrop to the lovers’ motions. The beloved’s sleeping has caused the lover to be more awake than they’ve ever felt. It’s all very heady.

Scottish crime writer Ian Rankin famously loved this song and gave The Mutton Birds some ink-time as one of his character’s favourite bands. Possibly we literary types gravitate towards people who might have read some books. (I remember when I was recording my second album in another band’s rehearsal space, the only book there was called Living with Tinnitus.) Who knows, Ian Rankin might just like the tune, since apart from the brilliance of the lyrical conceit, ‘While You Sleep’ features one of those indelible Don McGlashan melodies which he delivers almost at once. The first line is the title, like early Beatles (“Love, love me do”, “Help! I need somebody”, “She loves you yeah yeah yeah”, “Paperback writer, writer, writer”). No mucking around, state your business: “While you sleep ...” David Long’s choppy intro guitar riff is soon swept away by this gorgeous vocal in that classic Mutton Birds dynamic of jagged and smooth. The riff will come back later in the song, just slightly discolouring the optimism while leaving it in place, and safely banished again by loveliness. These are Don’s songs but the band always has its say. He will never be able to watch them sleeping.

The Chills – Look for the Good in Others and They’ll See the Good in You

Like some leaked tape from a therapy session, complete with the patient’s attempt to integrate a pyschologised self:

“Last week just for a while

I thought I found someone at last

The woman in my future

Was a child from my past

Oh that was cruel of fate to give me hope

The first time in two years

Now I’ve learned just who my friends

Are and no one really cares”

Martin Phillipps is one of those songwriters who was so much better than I first thought that I continue to doubt any of my judgements in that period. The snobbery was killing. For a period in the late 80s / early 90s he was as good as anyone anywhere. Seven or so years before, I didn’t see it at all. Okay, he got better, sure, and The Clean, well, that was their peak song-wise. After that, they played the variations. Marty was a developing human rather than a theme with reverb. Still, I was a fool. In following The Clean up the island, as mentioned above, it turned out we were also putting ourselves in the audience for that first iteration of The Chills. I thought they were cute and insubstantial. ‘Kaleidoscope World’? I didn’t want to live there.

“I used to look for too much

In the people that we are

You know we used to have a reason

For doing things the way we do

Sorrow was my reward

‘Cos I’m unhappy with me too

Now I’ve learned that I am me

And me is not the same as you”

Don McGlashan would have too much good taste to write that, and I need to make such a statement work positively in both directions. When Don looks back, he usually needs some particulars, a scene. He’s already in a short story. He sees characters and proceeds through elegant indirection – not a song about the killer, that would be too much, but one about the man who, unknowingly, sold the killer his rifle? Perfect. Martin Phillipps isn’t made like that: “But she’s lying there dying / How can I live when you see what I’ve done?” He’s always too much.

For Phillipps, writing is a way of seeing himself or trying to. The solipsism is necessary since inwardness is the first step towards insight. His vivid conundrum and, I think, his great subject, is how to learn what a person is while being one himself. “Me is not the same as you.” His gift is philosophical not dramatic, even when or especially when something dramatic has happened. “What can I do if she dies? / What can I do if she dies? / What can I do if she’s lost?” She’s dying but he can’t get over himself. It’s always his kaleidoscope world we’re asked to live in.

I don’t want to labour the contrast but if Don McGlashan wrote ‘I Love My Leather Jacket’ we’d hear about the purchase, the quality of the material, then some small detail about the funeral when the jacket was passed on. He’d really make us see it.

The Chills: “It’s the only concrete link with an absent friend / It’s a symbol I can wear till we meet again / Or it’s a weight around my neck while the owner’s free / Both protector and reminder of mortality.” Martin names it as a symbol, not bothering to work it up into one. His writing often has this quality of bareness and back-to-frontness.

Can we turn this lyric back into ordinary speech? How would it sound? Like this: “What does that leather jacket mean to you, the one that belonged to your friend who died?” “Oh, it’s a reminder of mortality.” It’s as if the words wants us to think always and immediately of meaningfulness. We don’t have time for anything else. The world not full of things but messages, private symbols. Is that how Phillipps made sense of experience?

It works for the singer but why does it work for others, for we who aren’t Martin Phillipps? (“And me is not the same as you.”) Because it emphatically does. It’s a great singalong song. Obviously songs are songs not texts. The ‘Leather Jacket’ riff is such a goodie, who cares about the words. I get it. Except Martin Phillipps is a singer songwriter. His voice is usually high in the mix. He has things to say and things we can hear. He’s not J Mascis.

The Chills in Berlin, c. 1987. From left: Caroline Easther, Martin Phillipps, Andrew Todd, Justin Harwood. - Caroline Easther collection

Back to my chosen song. As a title and a sentiment, ‘Look for the Good in Others And They’ll See the Good in You’ sounds like it could be on a Christian rock playlist. It’s sort of embarrassing on the face of it since, unlike say ‘There is No Depression in New Zealand’, this is not satire. That’s the dare in a lot of The Chills lyrics – can you cope with this much of a bromide? But something strange is happening here. The verses don’t quite add up. Does the singer’s account of what’s happened to him really bear out the title? Will they see the good in you if you look for it in them? Hardly. You’re more likely to find out who your real friends are and good luck with that (“And no one really cares”). It’s an enraging thing, this therapy. People are just so fucking unreliable. How can the hopefulness survive the disenchantment? Since that is what the singer longs for. I think of Martin Phillipps as one of our least ironic writers.

I love the moment when his breathing almost runs out on “the first time in two years”. It’s one of my favourite Phillipps vocals. He’s on or even over the edge. He wasn’t always so pumped up but his singing often carried this kind of gulp of self-surprise, some undimmed wonder at the strangeness of everything, including himself. Live, ‘Look for the Good’ was played faster and kicked off like The Ramones. (There’s a great version from the Gluepot in 1991 on YouTube. Again, you can hear all the words; he was a good enunciator and he wanted his vision to carry.)

That this all comes inside a rollicking bit of rock and roll is an amazement.

Phillipps concludes, against the bitter logic of the song, with his mission statement: “It’s great to be an adult and still believe the child in me.” The drums are just pounding away gloriously, and for a moment you believe him too and wish him well. But if you’ve been following the words, you also feel the heat of an accusation: leaving aside my personal failings (“I’m unhappy with me too”), you people let me down! Is that what it means to be a person? The doubled disappointment of your unrealised self and everyone else’s disregard.

That this all comes inside a rollicking bit of rock and roll is an amazement. We feel the stress placed on the word “sometimes” in the final verse when the singer, full of despair, pointless dreams, his “talent coming bare”, thinks that he is sometimes “set free”. It’s very fragile but just enough. A song then with a naïve wish which is undone by a moment’s reflection but which nevertheless sounds triumphant. Loud guitars, big beat, a singer popping the veins in his neck. Those punters at the Gluepot 35 years ago didn’t feel chastised. They felt lucky and lifted, even good in themselves, connected to each other, for a moment set free.

I saw the Chills whenever I could in their final phase, once in a small bar in off-peak Wānaka maybe 10 years ago. They gave it everything. I thanked Martin after the show. He nodded. It was cold outside. He was absolutely spent and they had to drive on somewhere else in the dark.

I don’t know if Martin Phillipps was ever convinced by adulthood. It didn’t sound like much fun to be in his band at times. Key allies appear in the wonderful Chills documentary by Julia Parnell and Rob Curry, still wondering at what went on. Decades after these hurts, Martin on-camera is genuinely working to understand these responses, still thinking about goodness and others. His friends also talk about his kindness and generosity.

Watching the film I was convinced all over again by his music and by his extraordinary courage. By then reminders of mortality were so urgent, he didn’t need the leather jacket. He was still playing the song though and ‘Look for the Good in Others’. Still rocking it, singing to the edge of himself. We wanted that, he knew it, and The Chills warmed up cold dark Wānaka with a feeling of possibility I still carry.