Combining an old-school get-the-job-done discipline with a progressive mindset, Bruce Lynch produced some of our finest, most successful songs of the 1980s, but there’s so much more.

In the 1970s, he became one of the most in-demand session bassists on the planet, who somehow squeezed in startling jazz performances with some of New Zealand’s best practitioners of the art. And in what seems like yet another life, in the 2000s he arranged and composed for the likes of the World Of Wearable Arts and the Power Rangers TV series. Somehow, there’s always more to uncover with Bruce Lynch, and only a proper memoir would do this chap justice.

For 60-odd years, Lynch has stayed afloat in the choppy waters of the music business; an amazing feat in itself. Despite this, he’s hardly a household name like his former wife, Suzanne Lynch (née Donaldson of The Chicks fame).

Bruce Lynch laying down some bass at Studios 301, Sydney. - Bruce Lynch Collection

Born on 1 June 1948 and raised in New Plymouth, Lynch hated the piano lessons his mother pushed him into but when his school pals at Spotswood College set about forming a band and announced their need for a bass player, Lynch raised his hand for the job.

“A friend of mine, Neil Cleaver, wanted to start a band. And of course, they had all these people that wanted to be singers and guitarists, but they didn’t have a bass player, so they asked if I could be a bass player, and I said okay.”

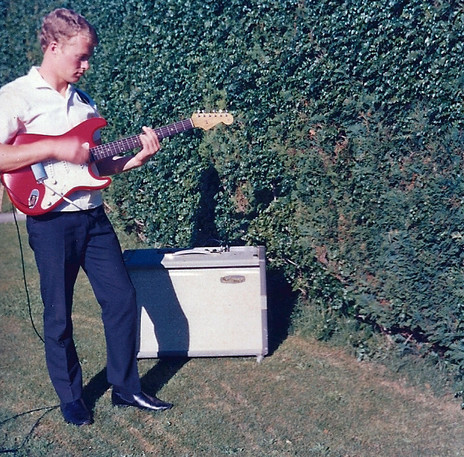

And so, an almost random event led to a lifetime of bass adventures. But it wasn’t quite that simple. As he didn’t have the money to buy a bass guitar, Lynch made his first one in his carpenter father’s workshop. The real revelation though, was when he got to see, feel and play his first Fender Stratocaster. The feel of the thing, the image, the music; it all mixed into a great desire to have a life in music.

Bruce Lynch with his first Fender Stratocaster - Bruce Lynch Collection

“I used to live just across the road from high school, and we’d come home at lunchtime and rehearse and listen to records,” says Lynch. “Among the many albums was The Shadows. I had The Rolling Stones, but I didn’t actually like them that much. Dave Brubeck, Dizzy Gillespie’s Dizzy Goes To Hollywood and Dizzy On The Riviera, Chet Atkins’s Hometown Guitar. That covers a lot of stuff, and I’ve still got them all.

“But also, there was a hairdresser in New Plymouth by the name of Galvin Edser. He was a jazz bass player. I heard him play with trios and stuff and I was trying to figure out what these guys were doing. I loved it but I just had no idea because they were way beyond what my experience was. His claim to fame was that he wrote to the Russian president at the time and said he wanted to be the first bass player in space. I kid you not.”

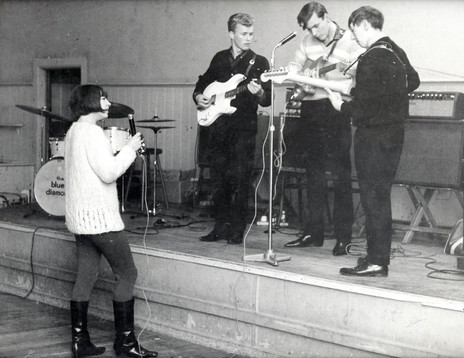

Dinah Lee rehearsing with the Blue Diamonds in New Plymouth, 1964. From left: Bruce Lynch, Murray Coplestone, and Midge Marsden. - Bruce Lynch Collection

That incident was reported by the legendary Midge Marsden, who was working for the Taranaki Herald at the time. And miraculously, Lynch ferrets out a newspaper report about a show Edser played with Midge backing Dinah Lee.

Hanging out with Marsden and other New Plymouth musicians was an introduction to a different way of thinking. “That’s kind of where I was introduced to the colourful aspects and alternative way of thinking [of being a musician]. There’s a certain lovely humour and vibe from people who approach life and express themselves in that medium. It’s what we do. We do give a shit, but ultimately, we don’t!”

White tie: Bruce Lynch, playing bass at the Bowl of Brooklands, New Plymouth, 1966. - Bruce Lynch Collection

There was another strand to Lynch’s musical education. “I did my first arrangement when I was 15,” he says. “It was crap but I put pencil to paper, and I’m still putting pencil to paper. What I love is the fact that you can pick up a pencil and a piece of manuscript and it goes from here to there and then somebody will pick up that part and play it … It’s one of those skills that’s been slightly lost, but with electronic scoring programs sometimes they’ll end up writing you.” Lynch still strongly advocates, on occasion, the good old 3B or 4B pencil, a sharpener and a rubber.

Bruce Lynch - at the steering wheel - with the Nite Lights, Taranaki, 2 December 1965. - Bernard Woods Studio; Puke Ariki, New Plymouth.

From the get-go, he found that having the ability to play any genre of music was emotionally satisfying and made a huge difference to his bank balance.

“Unfortunately, it’s been part of the landscape of being a musician in New Zealand. If you want to work you’ve got to pay the bills, make yourself useful, so someone comes along and asks if I can play in a certain style, and I answer ‘Yes’.”

In 1969, Lynch made the big move to the big city, Auckland, where he attended university – a ruse to allow him to soak up the nightlife.

“The great thing about university was that it got me to Auckland, and I ended up playing guitar, and was musical director for Robert Gennari, an Italian tenor, and that’s how I met Frank [Gibson Jr] and the rest. Robert’s manager knew a guy, Brian Curtis, who was opening a nightclub on Fort Street, and asked me to put the band together, so the first person I approached was Frank. ‘Hey man, I’ve got a gig!’ We didn’t know that Curtis was a major drug dealer. It didn’t last long but it was pretty funny. He went to prison, then he escaped.” When Brian Curtis died in 2013 after a lifetime of heists and daring prison escapes, the NZ Herald described him as “New Zealand’s most notorious criminal.”

Bruce Lynch, back row centre, with the Merv Thomas Octet, at Auckland's Peter Pan Band ballroom, early 1970s. - Bruce Lynch Collection

Depending on who you talk to, Auckland in the 1960s and 70s was either dead boring and looked like a communist city because everything was shut, or it was a hot spot for music and nightlife. Lynch simply remarks: “They were colourful days! Just lift the carpet!”

“After that we fell into a gig at a place called The Embers that was run by a Liverpudlian folk singer called Nick Villard, and he was so encouraging of jazz musicians. He had a recording set-up there as well and when people like the Basie band and the Ellington band came through, we actually had jam sessions down there that were recorded.”

Lynch’s can-do attitude and reliability soon saw him become a fixture on television pop programmes like Happen Inn as an arranger and member of the backing band.

“I played in the recording band and did many of the arrangements. Carl Doy rescued a few boxes from Radio New Zealand because they were going to throw those things out. There are two big boxes, which probably represents a couple of years’ worth, and it’s all handwritten.”

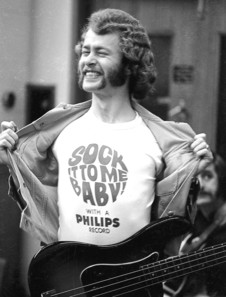

"Sock it to me, baby!" - Bruce Lynch in the studio, early 1970s

Lynch appeared on loads of local recordings going right back to the 1965 EP by self-described “Taranaki cow cocky” Woody Woodhouse, and gained steam from 1971 to 73 with releases by Suzanne, The Rumour, Christine Smith, Ken Lemon, Rob Guest and Larry Morris, on whose 5.55am album he contributed guitar, vocals, co-production, arrangements and “remix”.

Another job Lynch excelled at was playing in pick-up bands for touring international celebrities such as Shirley Bassey and Cilla Black. It was on one of these tours that he met producer/musician Tony Visconti, who went on to huge fame due to his decades-long association with David Bowie.

“I owe a great debt to Tony,” says Lynch. “I met him in New Zealand in 72. He was out here with Mary Hopkin, his wife at the time, and he was playing for Mary, and he used my double bass. And Tony, we just became great friends, we had a great time on the tour, and it turns out we both play classical guitar, and both play bass and we’re both arrangers. So, he said if you ever get to England give us a call.”

Having already achieved so much in his four years in the Auckland music scene – jazz gigs in nightclubs, hired hand on recordings, arranging and playing in a television music show backing band, helping out international touring acts – Lynch and his wife Suzanne took off on a holiday to England.

“We went there for a three-month holiday. I phoned Tony and he said, ‘Bruce, where are you? Are you here? Do you want to work? I’ll call you back’. And five minutes later he called me back and that’s how I ended up on that very first session, Randy Stonehill. I worked almost every day for the rest of the year.”

This was the start of a long friendship with Visconti, and Lynch’s busy session-work years in England, mostly playing bass on a terrific variety of recordings, from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Bruce Lynch with Tony Visconti, reunited. - Bruce Lynch Collection

“The studio period playing the bass in the UK was interesting because you do a whole lot of different stuff. Randy Stonehill was a singer-songwriter session and next thing you find yourself at Wembley and it’s a film session with Jerry Goldsmith or Dave Grusin or somebody.”

Among the artists Lynch applied his bass playing magic to from 1973 onwards were Leo Sayer, Mary Hopkin, the mighty Scott Walker and the queen of willowy experimental pop, Kate Bush (check out ‘Saxophone Song’ on her debut album, The Kick Inside). His skills were also exploited for orchestral and film soundtrack sessions (including James Bond films), and he performed on one of the odder albums of the 1970s, Deep Purple member Roger Glover’s audacious triple 1974 concept album, The Butterfly Ball And The Grasshopper’s Feast, which featured Dame Judi Dench.

“That was beautiful, that album. In fact, there’s a connection there because the Butterfly Ball was from the same people who produced the very first album I was on [Randy Stonehill’s Get Me Out Of Hollywood]. And on that very first session was drummer Chris Karan, who was Dudley Moore’ s drummer, and Elton John’s percussionist Ray Cooper. I was booked the day before to go in and do a 10-to-1 at Air London Oxford Circus, and that was obviously my audition, and then, ‘Can you come back at 2?’”

Lynch remarks about the skills of all-analogue audio engineer Bill Price and remains amazed at his nonchalant attitude towards the people he worked with during those first years in London, including pedal steel guitarist BJ Cole, Cooper, and out-of-the-box oddities such as comedian Spike Milligan’s son Sean.

“The funny thing is that I was just a young fullah from New Zealand going, ‘Oh yeah, that’s cool’. And it’s not until years later that you think, ‘I should have been paying more attention’. Without being obsequious or in awe. That’s probably what got me through a lot of stuff, because I’m not actually that good, it’s just that I have a certain amount of ‘Okay, let’s do it’, the Number-8 wire thing. But I could read. It’s interesting in that I probably made more money per note than anybody else during those singer-songwriter sessions.”

One of the last 1970s sessions Lynch undertook was with former Procol Harum keyboardist Gary Brooker. While the album, No More Fear Of Flying (1979) featured producer George Martin and well-known musicians including Dave Mattacks and Tim Renwick, for Lynch it wasn’t notable so much for the music recorded but a conversation that resonated with him. Keith Reid, who wrote the lyrics for Procol Harum’s big hit ‘Whiter Shade Of Pale’ was hanging in the studio. “I couldn’t resist,” says Lynch. “I said ‘Keith, what do the words of that song mean?’ and he said, ‘I have no fucking idea! It’s just words mate!’”

Rick Wakeman with Bruce Lynch, London, 1970s. - Bruce Lynch Collection

For Lynch, it backed up a comment he’d heard famed drummer Andy Newmark (Sly & The Family Stone) make: “When you’re doing a job with a singer-songwriter don’t listen to the lyrics”. “And it’s absolutely true,” says Lynch. “What the hell am I going to do on the bass to enhance fluffy stuff?”

That same year, before returning to New Zealand in 1980, he worked on albums by Rick Wakeman (with his old pals Tony Visconti and Frank Gibson Jr), celebrated folkies Richard and Linda Thompson, and former Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band member Neil Innes, among others.

While many of the sessions were one-offs, one artist that Lynch struck up a long-term friendship and ongoing musical relationship with was Cat Stevens (aka Yusuf Islam), beginning with the 1974 album Buddha And The Chocolate Box. With Suzanne accompanying as backing singer, Lynch became an intrinsic part of the touring band during that decade.

It was due to his work on a Cat Stevens song in 1976 that Lynch – many years later – found that he’d been credited with creating one of the first electronic dance tracks. ‘Was Dog A Doughnut?’ anticipates the groovy kind of backing tracks that early hip-hop artists often used, and features jazz legend Chick Corea on electric piano. “That was 1976 and we were in a studio in Copenhagen,” says Lynch. “I had an ARP 2600 and we were just mucking about.”

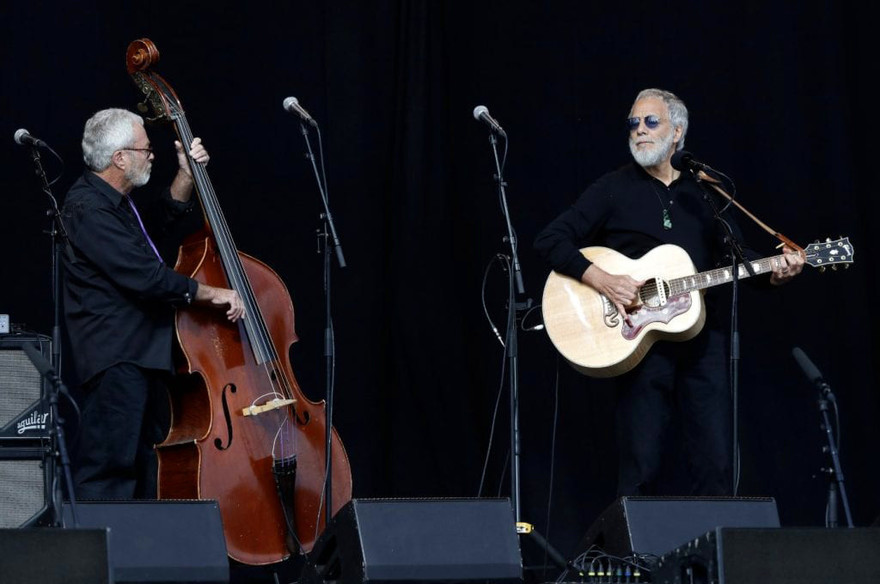

Fast forward to 2017 and Lynch was back in France recording tracks for Yusuf’s album, King Of A Land (2023). A few months later, he was asked to remaster the singer-songwriter’s early Decca recordings from the late 1960s, including ‘Matthew & Son’. While working away on the remasters he got the cheeky idea of creating a composite of Cat’s very first single, ‘I Love My Dog’ (1966) and the electronic track, ‘Was Dog A Doughnut?’. “I sent it to him, and he said, “That’s great!” This fusion has yet to see the light of day, but Lynch was invited back to perform on Tea For The Tillerman 2 (2020) as well as play acoustic bass and keyboards on King Of A Land.

Lynch also performed with Yusuf/Cat at the remembrance service held on March 28, 2019 in response to the Christchurch mosque shootings.

“I love that man, he’s a very clever dude,” Lynch says of Yusuf. “He’s a complex individual, a deep thinker.”

Bruce Lynch with Yusuf Islam aka Cat Stevens, at the National Remembrance Service, in Hagley Park, Christchurch, 29 March 2019 - Bruce Lynch Collection

Have we forgotten something? Yes, we have. Because apart from recording sessions with all of the above (and many more) Lynch had a contingent of expatriate New Zealand jazz musicians to hang out with. The 1970s saw an explosion of jazz-rock fusion and several of our top jazz players were integral to the UK scene at the time, including keyboardist Dave MacRae (who played with Robert Wyatt’s Matching Mole), saxophonist Brian Smith (who played with Maynard Ferguson and the band Nucleus) and the late, lamented drummer Frank Gibson Jr (who, with Lynch, was a founding member of the popular London fusion group Morrissey-Mullen).

“We did loads of gigs with Morrissey-Mullen but they didn’t make an album until the early 80s. The only recording we did was at Abbey Road using the first digital recorder. It was the first non-classical recording on a digital EMI machine.”

It turns out that Lynch was also a member of Nucleus for a time, performing with them for an Italian tour but nothing was put down on tape. And that’s how it went for Lynch. Between his busy session recordings, he somehow managed a busy schedule of late-night jazz gigs, some of which haven’t even been noted for posterity. “I even did a gig with [pianist] Dudley Moore once, when his bassist was sick.”

These sound like exciting times, but Lynch is candid about his attitude. “Exciting? I don’t know what the word would be. There’s a job to do and when you’re going into a jazz gig you’re thinking, ‘What tunes is he going to play and do I need core charts? Do I know them, or are we going to do the same changes? How’s it feeling at the bottom end with the drums?’ You haven’t got time to be excited. But you know when it’s good.”

--

Read more: Bruce Lynch, 2: home and away

Discogs: Bruce Lynch’s production credits