“I was in the right place at the right time,” explains Wellington-born Samoan rapper, street dancer, and graffiti artist Kosmo Faalogo, known over the years as Frosty K, K.O.S 163, Kosmo, and most colloquially, Kos. Throughout the 80s, 90s and 2000s, he left an indelible mark on hip hop across Aotearoa, thanks to his role in a series of seminal groups: Noise and Effect, The Mau, Rough Opinion and Footsouljahs, as well as numerous ancillary duties.

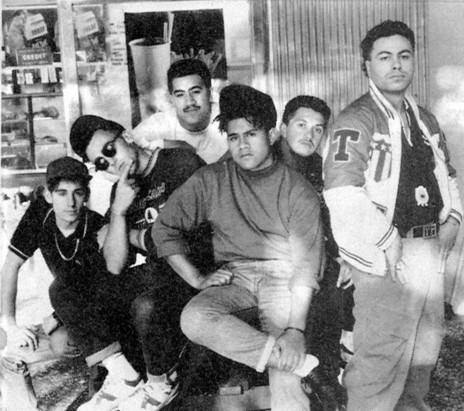

Footsouljahs, clockwise from top left: Pomby'ia (Ali Cabano), Shogun, DJ Raw (Ian Seumanu), Flowz (Fiso Siloata) and K.O.S 163 (Kosmo Faalogo).

As Kos puts it, he was one of those kids who got passed through family, which meant he spent time in Auckland, Samoa, and the City of Carson, 21km south of downtown Los Angeles, before returning to Wellington in the early 1980s. These experiences gave Kos a worldly quality and the skills to make a name for himself in the capital.

During his years in Carson, electro music, early hip hop, and street dance was a key part of life for Samoan youth in California. In Carson’s Foisia Park (formerly known as Scott Park) and the neighbouring cities of Compton and Long Beach, he spent time with the American Samoan street dancers Donald and Danny Devoux of the Blue City Strutters – who led the legendary hip hop band Boo-Yaa T.R.I.B.E – picking up the fundamentals of strutting, boogaloo, popping, and tutting along the way.

“I came back to New Zealand when I was 16 or 17,” says Kos. After spending a couple of months in Auckland with his aunt and uncle, he headed to Wellington to live with his brother. Not long after, he went into the city on a Friday evening and saw a group of b-boys breakdancing in Manners Mall (now Manners Street). One of them was Justin Campbell aka Dr Baggy, who appeared in the New Zealand version of American RnB singer Irene Cara’s ‘Breakdance’ music video in 1984. Another was Vinny Viule, later known as DJ Rock-It V. Kos had to get involved.

Kos’s dance moves impressed the b-boys at Manners Mall, and they invited him to Dr John’s, an all-ages nightclub.

The guys were impressed by his dance moves and invited him to hang out with them at Dr John’s Nite Spot, an all-ages nightclub on Courtenay Place. “I said yes, and as they say, the rest is history,” he laughs.

For the capital’s teenage disco, funk, electro and hip hop fans, Dr John’s was the place to be. “You wanted to wear your best sneakers, meet girls, and get your swag on,” Kos laughs. A big drawcard was the young Māori DJ Tony Pene aka DJ Tee Pee, the shining star of the Wellington nightclub scene of the era. Tee Pee didn’t just DJ though, he would get on the microphone and rap as well. “Tee Pee at Dr John’s was the first time I saw someone DJ and rap at the same time,” Kos remembers. “I thought, whoa, this dude is dope.”

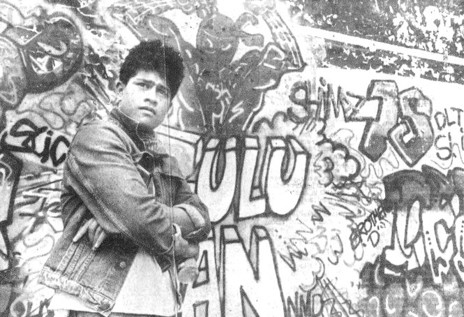

Given their interest in street dance and hip-hop, Kosmo, Dr Baggy, Rock-It V, and a few of their friends formed the dance crew Chain Reaction and, later on, Twilite Thrillz. During the mid-80s, the guys used to bus around the country. They were overjoyed to find breakers dancing to electro and early rap everywhere they went. Hand in hand with dancing, he took inspiration from early hip hop films such as Style Wars (1983) and Beat Street (1984) and started doing graffiti art around the greater Wellington region under the alias Frosty K.

Through these cultural vectors, Kos met the b-boy and rapper Dean Hapeta – aka D-Word and Te Kupu – and the graffiti artist and DJ Darryl Thomson aka DLT (then DLT Slick), both foundational members of the pioneering Aotearoa hip hop group Upper Hutt Posse. Reflecting on the era, Kos appreciates the naivety that came with it.

K.O.S 163 in front of a DLT graffiti piece.

“Back in the day it was something new,” he says. “Everybody was fresh, and everybody was so excited about this hip hop shit. We were all trying to use every cool word we knew in one sentence.” He pauses before giving an example with a laugh. “Yeah man, I’m just chilling. I’m def and I’m out.”

As Kos remembers it, Dean was the first person he met who was ordering records from overseas. Dean would read the NME (New Musical Express) newspaper, find shops that offered mail order and send money overseas to get copies of highly sought after electro, hip-hop, reggae and dub records. He’d bring them into town and give them to DJs such as Tee Pee and Rhys B to play, which as Kos sees it, helped advance the soundscape of Wellington nightlife.

While they were hanging out, Dean and Upper Hutt Posse started getting more serious about rapping. They were making cassette tape demos at home, laying the foundations for their first single, the legendary ‘E Tū’, recorded for Jayrem Records in 1988. Between hearing Dean’s demos and freestyling with him on the weekends, Kos developed the confidence to start rapping. “I thought, if he’s doing it, I’m doing my shit as well,” he says.

In the late 80s, Kos hung out at Tony Barrett’s iconic Jam Hair Co hair salon (then located on Cuba Street). Tony used to get Kosmo and the guys to do graffiti pieces for him. At Jam, he met a British rapper who went under the alias Crafty Cockney (CC).

Noise and Effect, K.O.S 163 centre.

They got together with Rock-it V and a producer Christiaan Ercolano aka Crispy Fresh, who later on became one-half of the House music duo House of Downtown and formed their first crew, Noise and Effect. “Our first gig was a birthday party for one of the girls who used to come to the saloon,” Kos says, before continuing with a laugh. “We got too pissed, did the gig, woke up the next day hungover and didn’t remember the gig. We must have been pretty wack.” Thing is, they weren’t wack.

Two weeks after their first performance, Dean and Upper Hutt Posse invited them to travel up to Auckland with them to play a show at Club Roma, a nightclub located underneath the Civic Theatre on Queen Street. Coincidentally, Club Roma was also where the rappers Otis Frizzell and Mark James Williams aka MC OJ & Rhythm Slave impressed Murray Cammick enough to score a deal with his Southside Records label.

Back in Wellington, Kos started running into a fellow Samoan hip hop fan who wore glasses without any lenses in them, Kas Futialo, later known as Tha Feelstyle. In 1987, he was the winner of the first-ever rap competition in New Zealand history, an event organised at a community hall in Taita by DJ Rhys B and Mark Cubey from the local student-radio station Radio Active 88.6 FM (then 89 FM). Kas had skills and Kos invited him into Noise and Effect.

When they were performing live, Kos made a habit of flipping the chorus from ‘Coolin’ in Cali’ by the Los Angeles hip hop group The 7A3 into the phrase ‘Coolin’ In Welli’. He did the same thing with ‘Going Back to Cali’ by LL Cool J, rendering it as ‘Going Back To Welli’.

Jason Harding aka DJ Clinton Smiley, who sometimes worked as a music journalist, used to occasionally review their gigs for student magazines and street press. He started abbreviating Wellington to Welli in his writing and it caught on. “A lot of people don’t know, but we coined the phrase ‘Welli’,” Kos says. “We’d shout it at shows and from there it went mainstream.”

By 1990, Crafty Cockney (CC) was out of the picture and Kos, Kas, and Rock-it V had formed a new hip hop group, The Mau, named in homage to a non-violent movement for Samoan independence from colonial rule.

Kos, Kas, and DJ Rock-it V were influenced by socio-politically aware US hip hop acts like Public Enemy, X-Clan and Paris, who adopted strong pro-Black American stances. However, they quickly understood they needed to put a local twist on those Afrocentric groups’ ideologies in their own music. “We thought, let’s take our Polynesian and Samoan culture and talk about it in a similar way,” Kos explains. “We were trying to rap about growing up in Aotearoa as a Polynesian and spit knowledge that was good for the youth.”

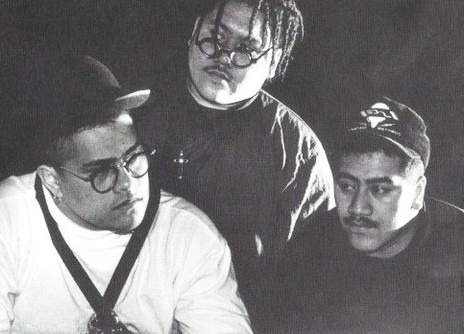

The Mau.

Unfortunately, they quickly ran into a hitch. “People thought we were The Mau from Samoa,” explains Kas. “I said, just translate it into English.” The translation was Rough Opinion. “That’s what it is,” he continues.

As Rough Opinion, they had the opportunity to go on tour with the Auckland funk-rock band Supergroove in the early 90s. At those shows, they connected with a generation of Aotearoa hip hop artists including Dam Native, Slave & Otis, DJ Manuel Bundy and Urban Disturbance (formerly Leaders of Style). “To this day, we have deep connections in Auckland through Dam Native,” Kos explains.

The Aotearoa Hip Hop and RnB legend Che Fu was still in Supergroove then and he loved having them on the road. “They just blew me away,” Che enthuses. “Two crazy Samoan rappers with dreads and a real Cypress Hill type of rap style. They would wear combat boots, jump up and down, and break stages. I loved them.”

Rough Opinion’s touring opportunities came through Supergroove’s original manager Stuart Broughton, formerly of Monitor magazine and The Dog Club. Kos was just beginning to promote club nights and concerts under his Phunk Republic brand, and soaked up everything he could from Broughton. “I used to stay up with him after the shows,” he recalls. “He’d say things like, ‘I can see Supergroove hiring a big plane.’ I was learning to be a promoter at the time, so being around guys who thought big and put it out there was really dope.”

Although Rough Opinion didn’t release any music commercially during their run, they did have the opportunity to record a song about safe sex called ‘Dam Dem Funky Hormones’ for a New Zealand television documentary, Prime Sex, which gave them useful studio experience before they went down different paths in 1993.

rough opinion blew che fu away. “They would wear jump up and down, and break stages. I loved them.”

Kos shifted his focus towards nightclub and concert promotion. Under his Phunk Republic banner, he hosted Wellington performances by Dam Native, Ma-V-elle, Che Fu, DJ Subzero, Time Bandits (Hamilton), and numerous other Aotearoa hip hop and RnB acts, before establishing an accompanying online hip hop website for the brand. In the process, he created a valuable networking platform for the still-nascent scene.

Kas on the other hand, started playing shows with Gerrard Tahu’s group Gifted & Brown, which included a young Bill Urale aka King Kapisi, Mara Finau (formerly of the Holidaymakers), Atawhai Tibble aka MC AT, and DJ Raw (a gifted turntablist and DJ battle champ, who was mentored by DJ Tee Pee).

The following year, Gerrard received an invitation to travel to America and join the former Wellington-based street dance choreographer and musician Steven Daniells-Silva aka Suga Pop’s band. After he left, Kas, Kapisi and Raw briefly formed a group called The Overstayers before Kapisi relocated to Auckland to further his music career.

It was during these years that Lucia Ablett, aka Emcee Lucia – who later became the first woman in New Zealand to release a hip hop album – first met Kos. “He was this super-confident stocky dude with an afro, and he was just so easy to talk to,” she says. “Kos led the conversations and created the vibe. It was about making our own unique version of hip hop that was specific to the Polynesian experience in Wellington.”

In the wake of Gifted & Brown and Rough Opinion. Kos and Raw became weekend drinking buddies. Kos was living just off Courtenay Place on Blair Street and his flat became an unofficial meeting spot for the next generation of Wellington rappers like Lucia’s cousin, Fiso Siloata aka Flowz.

Their first performances were billed as The Rough Opinion Cypher at Kosmo’s Phunk Republic nights, followed by a show under the moniker Pasifikan Me (a play on the US crime drama American Me), in which they performed with a Samoan cello player. They settled on the name Footsouljahs in 1994. “Kos had this idea that we had to be the foot soldiers,” explains Fiso. “We needed to be the voice of our people. I said, ‘What’s a foot soldier?’ He said, ‘They’re the first guys on the frontline in the military.’ That was the sort of mindset he always had.”

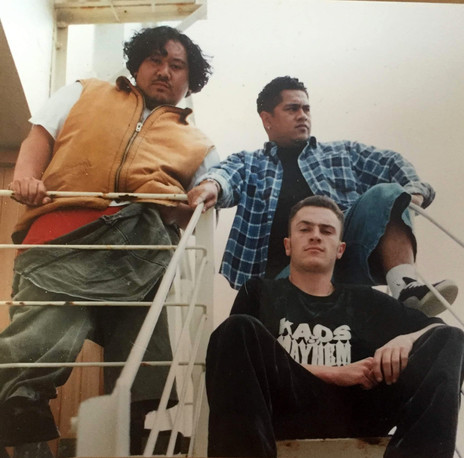

Rough Opinion: Kas tha Feelstyle, K.O.S 163, and Mikki D - Publicity photo

Not long after they renamed themselves, Fiso’s younger brother Ali joined the group, as did two other local rappers Koner and Del C. “A lot of the older guys had moved to Auckland, so we had to encourage the younger generation,” Kos remembers. “A lot of guys who could have kicked in the door and left it open didn’t do that,” he continues. “We were about kicking in the door and leaving it open. Our philosophy was – and still is to this day – that there is more than enough clout, shine, and opportunity for everybody.”

At the time, the New Zealand music industry focus was on major-label artists based in Auckland. By staying in Wellington, Kosmo and the Footsouljahs were going against the flow. During the late 90s, they embraced a resolutely DIY approach and made sure to network with emerging hip hop crews, among them Hamofide from Porirua. “We were always trying to link the city and give younger cats the encouragement to do this,” Kos says.

Raw purchased studio equipment and taught himself how to make beats, produce, and record. Kos began to educate himself about management, publicity, T-shirt screen printing, CD duplication, and distribution. They also taught themselves how to make music videos. “We learned as we went, and from doing that, we learned more skills,” he explains.

“Kos was our leader, basically,” says Raw. “He took the lead and came up with all the ideas for marketing, gigs, t-shirts, and all that kind of stuff. His concepts are quite deep because he has done a lot of research into history. He knows a lot about the Black Panthers and he is quite into his art and culture.” Fiso adds: “Kos has always followed indigenous independence movements. He taught us about being consciously involved with supporting things that align with hip hop. That was a big part of our journey.”

“Kos was our leader, basically,” says Raw. “He taught us about being consciously involved with things that align with hip hop.”

More than anything, though, what Kos and the Footsouljahs were the most renowned for was their stage show. From the word go, they were gigging around the country wherever they could, but when they performed at the Christchurch Hip Hop summit in 2000, things hit a boiling point.

“That hip hop summit was monumental for us because it allowed us to see like-minded individuals,” reflects Mark Sagapolutele, aka Mareko, from the South Auckland hip hop supergroup Deceptikonz. “When we saw Footsouljahs, we were like, I’m Fiso’s biggest fan after that performance, I’m Kosmo’s biggest fan after that performance. These guys are exactly like us. We thought we were the unicorns. Nah, there are other guys exactly like us. It was mean.”

In 2001, Footsouljahs released their first EP, Stylz Deliveriez Flowz through their own independent label, 2Much Records. By this point, the group’s lineup had settled into Kos, Fiso, Raw, Ali and a new member, Shogun. At the time, the Evening Post described it as “a classy slab of – yes – definitely and defiantly ‘indigenous’ hip-hop.”

Three years later, they released their debut album Puttin’ In Work, which came accompanied by several visually powerful music videos. Within the scene, Puttin’ In Work was celebrated as a hardcore classic and received positive reviews from local hip hop focused media like Back2Basics. After the release and promotion of the album, Fiso began the process of recording his debut solo album In The Heart of The City, eventually released in 2008.

Building on his merchandise experience, Kos established his own street fashion clothing labels. He also continued to work in nightclub and concert promotion until the 2010s, when he began travelling around Australia and Southeast Asia before basing himself in Sydney, where he lives and works to this day. “Just the other day,” says Kos, “I was sitting outside a café near Bondi Beach and someone yelled out ‘Footsouljahs!’” The guy came over and talked about how he remembered seeing the group play in Hamilton when he was younger.

Thinking back over his decades of involvement in Aotearoa hip hop, Kos offers up some final thoughts, or more aptly, words of hard-earned and well-lived advice. “If I was going to say anything to new artists coming out now, I would say learn how to do things yourself. When your career depends on other people, you’ll always be waiting. It’s in your interests to learn the skill sets to get out there and do it.”

--

Interviews and research conducted by Phil Bell aka DJ Sir-Vere and Martyn Pepperell

Mai FM: Aotearoa Hip Hop podcast