It’s the simple questions that will throw you. Like, “Do you think there was a local disco and funk scene back then?”

And you would think after conducting about 20 interviews for Heed The Call! (Whakarongo, Nga Tamariki) – a compilation of New Zealand funk and disco from 1972 to 1982 – I’d have a good idea. But I don’t, and even though I’ve thought about it a fair bit since, I’m still only halfway to a definitive no.

What I do know is that, for better or worse, the New Zealand music scene during the 1970s were a great production line for musicians. Despite the conditions.

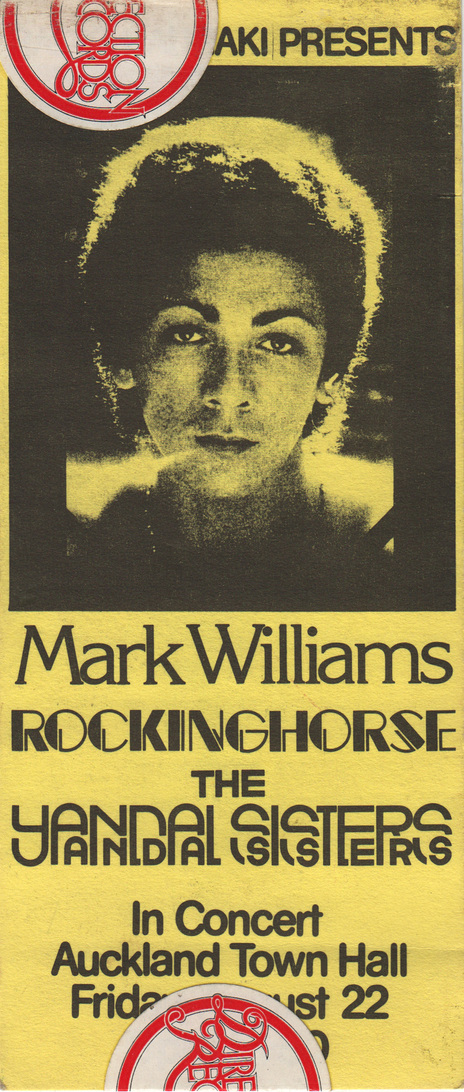

Mark Williams, August, 1975, at Auckland Town Hall with Rockinghorse and The Yandall Sisters - an all EMI line-up.

Not only did The Inbetweens, one of the bigger pub acts of the 70s as well as one of the most media-shy, have to use their socks to plug holes in the wall of one of the band flats a publican accommodated them in, they also copped attitude for a being a bunch of pākehā wanting to play funk.

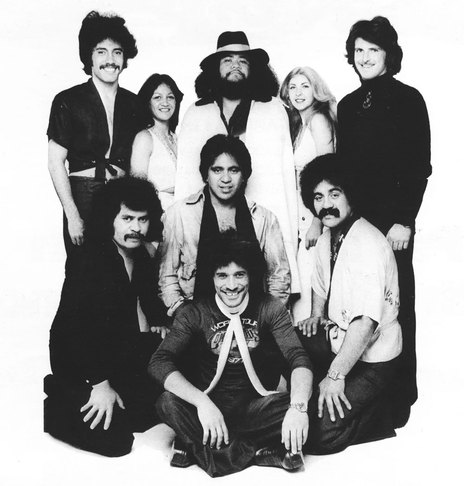

The Inbetweens at the Ferrymead Heritage Park, Christchurch, 1977. From left: David Bailey, Neville McCarthy, Len Worthington, Chris McCarthy and Tony Rabbett.

Some of that reaction can be put down to patch protection. DJs and live bands often swapped sets during the night and it wasn’t the done thing to stomp on one another’s material. But the American DJ at Wellington’s Lion Tavern would get fairly hostile when he saw some white guys banging out the Isley Brothers.

And if The Yandall Sisters were playing the more upmarket dine-and-dance circuit, the conditions were still lousy. The three young women had to find broom cupboards in which they could get changed and apply makeup. In one Auckland venue, they would have to arrange the concertina doors into an ad-hoc green room while the wait staff worked around them.

THE INBETWEENS COPPED ATTITUDE FOR BEING A BUNCH OF PĀKEHĀ WANTING TO PLAY FUNK.

So yeah, it was a different time with very different expectations of our live bands. Compared to most bands kicking off today, they were less creative entities with a singular voice than live jukeboxes. Punters everywhere expected to rock up to their local pub each week and see a completely different band playing fairly predictable sets.

Still, if there was an evolution toward dance music, it was also driven by the crowd. Inbetweens guitarist Chris McCarthy saw it from the stage. Rock music dominated in the early 70s, giving way to disco flavours by 1976. It was why McCarthy wrote the track ‘Mr Funky’, which was about a styling guy they almost used as a barometer of the dance floor. If he was dancing, others would follow.

As a result, says Collision horn player Mike Booth, it was normal practice to spend a day sitting around the radio, incrementally learning a new song to the point it could faithfully be reproduced that night: as they didn’t have tape recorders this was only possible due to radio’s high rotation policy. But when you got down to it, the music bands were still playing across-the-board genres with a heavy focus on current radio hits, and a couple of slow dances and hoary classics for the grandfolks. They were paid to keep the crowd entertained and the crowd wanted the hits. Save your originals for the shower, thanks very much.

But musical emphasis shifted from band to band. If the Inbetweens were wary of going too far to the funk for fear of alienating the crowd, it was pretty much all Collision wanted to play.

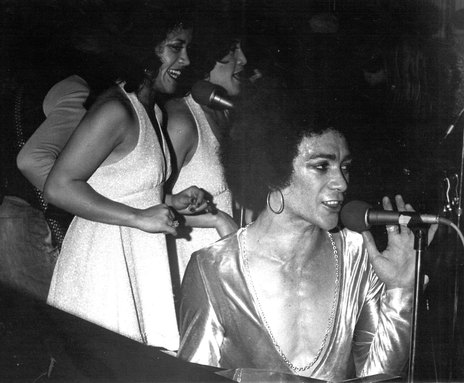

Collision with Dalvanius and the Fascinations - Murray Cammick collection

This was a deliberate choice from Collision, which spent its earliest days in Tokoroa, called Shriek Machine. Barely out of their teens, they had no intention of being yet another pop band: they wanted to go hard. Yet there were still dependent on covers, at least until they hit the studio in Australia.

Another young band, Golden Harvest – originally called The Brothers – had a similar outlier sentiment, although they expressed it in a more rock-oriented direction. Again, the band relied on cover versions and if it’s now known for sunshine grooves (‘I Need Your Love’) it was only under duress.

The interesting thing here is that although Collision came from Tokoroa, and Golden Harvest from Turangi – on the other side of Lake Taupo – they never knew much about each other. Because it’s easy to forget, when everything in the world seems only a click away, the isolation of the era. If you wanted to find or hear something new, it took real effort, especially when it came to music. Sure, records were available, but there was a 40 percent sales tax on them. The arts were hardly a focus of 1970s New Zealand.

Kevin Kaukau does his thing - Golden Harvest. - Simon Grigg Collection

So if, by scene, you’re thinking about a collection of vaguely like-minded individuals who maybe got together on occasion to share thoughts, ideas and maybe band members, well, not so much.

But, as mentioned, what scene there was did forge hardened musicians. You couldn’t survive otherwise. The North and South Islands had their own brewery-run circuits, Lion and DB, and each band would spend months trundling around each stop, playing (with variations) Tuesday through to Saturday evenings and practising most mornings. As a bonus, each venue would provide (sometimes squalid) accommodation for bands.

If you weren’t working on your set, you were driving to the next venue: this was music as blue-collared labour.

This was bad enough for groups but consider Mark Williams. He toured alone and would encounter a completely new set of variously abled musicians every week, and he would have to teach them his entire set in a day or two. And when he wasn’t doing that, he was being abused for the clothes he wore.

Mark Williams, circa 1975 - Phil Warren Collection

Williams never saw himself as a disco kid and had to be heavily cajoled into recording his first hit, ‘Yesterday Was Just the Beginning of my Life’ – the first version he heard sounded to his ears like AC/DC. But he enjoyed the result enough that he wanted to show it off at his next gig. It cleared the floor. Usually, the message was “Just the hits we know mate, just the hits”.

TRYING TO REACH THE “BIG TIME” IN AUSTRALIA MEANT STARTING AT THE BOTTOM AGAIN.

But it was one of the ironies of the time that groups (such as Williams’s first, The Face, from Dargaville) would enter the national music showcase, The Battle of the Bands, in the hope of moving up the food chain. The grand prize was a trip to Australia to have your shot at the big time, except that in this case “the big time” meant starting at the rock bottom again. Touring a country as big as Australia in a crappy van was fun for about five minutes: band after band shipped themselves over only to burn out, break up and slink home.

On the other hand, it was also one of the tragedies of the time that busting your back performing was a higher priority than recording.

Playing live was how bands earned coin: there was no money to be made by entering the studio, there was only playing time to be lost. Which, tragically, is why Leo de Castro – one of the greatest voices of his generation – has the merest of recorded legacies. Even then he still lucked in, making the switch to Australia before being all-but broken by the New Zealand circuit. Which is just as well, because he quickly revealed a singular knack for self-destruction, substance abuse and unreliability: it got so bad other band members would be assigned to make sure he made it to gigs.

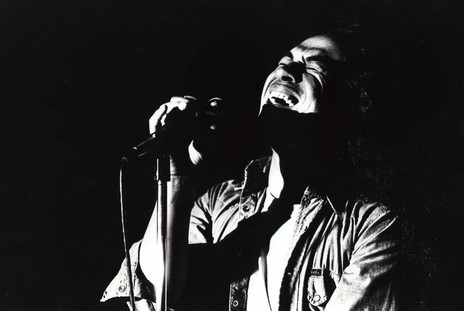

Leo de Castro, Sydney, 1973 - Simon Grigg collection

Some groups, such as Collision, saw recording simply as a means of memorialising their live sets. They had few expectations of selling funk to the Australian rock audience. When they were then pushed to record their own material, it was almost as though they didn’t know how. As with Ticket, they resorted to jamming – and when they found a groove they dug, they would stretch it out into a song.

Collison in Wellington, 1975 - Murray Cammick

Unfortunately, one of their best ideas – updating traditional Māori music – was dismissed by Sydney’s Māori community as disrespectful. Undeterred, their patron Dalvanius eventually returned to New Zealand where he used the notion to create his No.1 hit, ‘Poi E’.

Dalvanius and the Fascinations, Sydney 1970s. - Phil Warren Collection

Thankfully, Wellington had producer Alan Galbraith, who in 1973 had returned to New Zealand with the sound of UK’s Hot Chocolate ringing in his ears. It was a sound he then bestowed on the likes of Mark Williams, courtesy of seasoned touring veterans (Rockinghorse and Redeye) who had shown they could turn their hand to any sound you wanted.

Auckland’s unsung studio hero was Phil Yule, an engineer at Stebbing studios in the mid-1970s who would take every opportunity to experiment with effects. It was his playing around with the kick drum and bass guitar sounds that put the greasy, sleazy groove into the Inbetweens’ ‘Mr Funky’.

But the real takeaway from this experience is all these players had done their time: they could turn their hands to anything and make it sound authentic. From The 1860 Band (Wellington) to Ticket (Auckland) to Collision (Tokoroa) and the almost-unheard of Totals (Auckland), these players could all play.

The downside was that their apprenticeship didn’t encourage songwriters. If Chris McCarthy tried, he could only do so hunching over in a quiet(ish) corner, singing guitar lines into a tiny recorder. Even then his efforts were often met with audience indifference. Bah.

So, let’s ask that question again then: Was there a New Zealand funk and disco scene?

Only if that’s what the audience wanted.

--

Alan Perrott wrote the liner notes, and co-compiled with John Baker, the compilation Heed the Call! Whakarongo, Nga Tamariki! 17 Prime Soul, Funk and Disco Cuts from Aotearoa 1973 to 1983 (Vostok, 2017).

--

Nick Bollinger reviews Heed the Call! for RNZ National.

Grant Smithies picks four favourites from Heed the Call!