Watch: Don’t Let It Get You trailer, 1966.

--

Of all the genres to be tackled by New Zealand’s fledgling independent film industry in the 1960s and 70s, you might think the musical would appear at the bottom of the wish list. Musicals are expensive and complicated to shoot, typically involving large casts, extravagant sets and highly complex choreographed set pieces.

Not only that – and rather like porn films – they are usually hampered by gauche and clumsy plots that propel their characters from performance to performance. Viewed in this context, the 1966 Pacific Films musical Don’t Let It Get You stands not only as a testimony to the pluck and audacity of its intrepid creator, John O’Shea, but a valuable archive of mid-60s New Zealand popular culture.

Featuring an all-star cast, including a young Howard Morrison and an even younger Kiri Te Kanawa, its press release promised “a tonic film that doesn’t let the blues get you. When it finishes, you feel as if the time has gone too fast and you leave the theatre wanting to see it all over again.” And while that optimistic assessment was not shared by serious film critics of the day, Don’t Let It Get You certainly deserves, with the benevolence and hindsight of over 50 years, a second look.

By the time John O’Shea had decided to embark on Don’t Let it Get You, he had already completed two feature films, Broken Barrier (1952), and Runaway (1964). These proved his jaw-dropping ability to forge an industry out of nothing but a borrowed camera, a Moviola, a hot splicer, some basic lighting, along with a formidable intelligence and passion for the art of film.

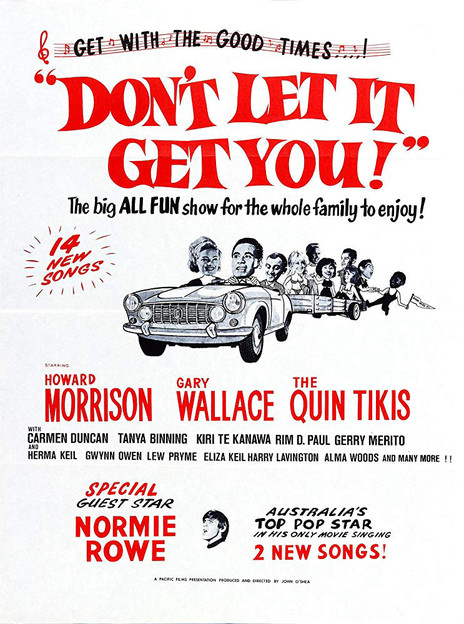

Poster for Don't Let It Get You - Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Despite audience bewilderment over Runaway, O’Shea was undeterred. He had found a new cause to rail against. The Mazengarb Report on Juvenile Delinquency had been released in 1954 and a newspaper-driven “moral panic” followed in its wake in which society’s ills were blamed on this relatively new demographic “teenagers”. As usual, the weekly newspaper Truth led the attack on the declining morals of New Zealand youth.

O’Shea’s response was to conceive an irreverent musical which promoted the values of freedom, youth, non-conformity and racial unity. He placed these themes in a loose narrative that borrowed heavily from recent British examples, Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and John Boorman’s Catch Us If You Can (1965). Prior to this the pop musical had been dominated by Hollywood’s showcases for major stars such as Elvis Presley, Ricky Nelson and Fabian but unlike their well-groomed singing/dancing/acting American counterparts, the members of The Beatles and the Dave Clark Five made an asset of their native wit and irreverent attitudes. The original version of Alun Owen's Oscar-nominated screenplay for A Hard Day’s Night had judiciously supplied the amateur actors with short one-liners (in case they couldn’t act), but they were naturals, and their energy and personality lit up the screen.

O’Shea borrowed many elements from A Hard Day’s Night, including the black and white semi-documentary style and irreverent humour, but most of all he expanded on its counterculture themes of Freedom and Play Power. In contrast to his previous homages to the French and Italian new wave auteurs, this one was designed to appeal not to intellectuals but to the emerging New Zealand teen culture.

But what distinguishes Don’t Let It Get You from its British counterparts is its fresh view of post-colonial race relations. It depicts a conflict-free zone of Māori and Pākehā getting along, side by side with everyone prospering without compromising their own cultural heritage. It starred a range of current musical icons, including New Zealanders Howard Morrison, Kiri Te Kanawa, Lew Pryme and Quin Tikis drummer Gary Wallace (aka Gary Wahrlich), alongside Australian pop star Normie Rowe and actors Harry Lavington and Carmen Duncan.

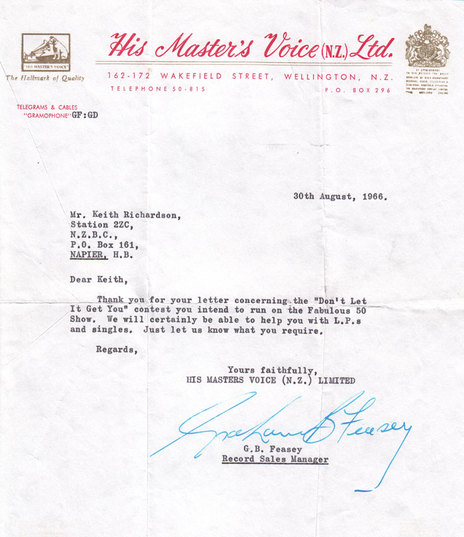

His Master's Voice, then the biggest record company in the country, helps influential NZBC deejay Keith Richardson run a Don't Let It Get You contest on his radio show. - Keith Richardson collection

The script, rather than being a complex narrative, provides little more than an excuse to showcase these performers and to cram in as many musical numbers as possible. This time O’Shea stepped aside and commissioned Downstage playwright Joe Musaphia to write the script about a pop festival in Rotorua, conveniently the hometown of singer and co-producer Howard Morrison. Sydney based drummer Gary Wallace hocks his drums and flies to Rotorua to perform at Howard Morrison’s summer music festival. He meets and falls in love with Judy Beech (Carmen Duncan) who is also visiting with her mother. The obstacle to his goal comes in the form of fellow suitor William Broadhead (Harry Lavington) but love triumphs in the end and is celebrated in the film’s final concert sequence.

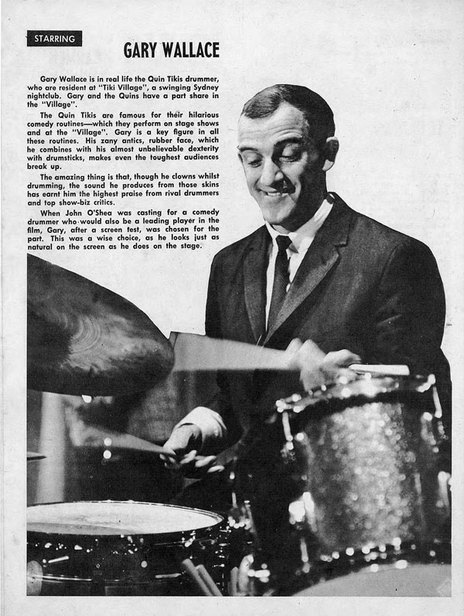

Gary Wahrlich in the Don't Let It Get You programme.

Nothing surprising there but the plot provides a vehicle for the film’s original songs, composed mostly by Patrick Flynn. With titles such as ‘It Takes Two’, ‘She’s the Girl’, ‘You Didn’t Make Me Cry’, ‘Why Am I Alone Now’, ‘My World Has Gone’, ‘She’s the Girl’ and finally ‘Liv’in and Lov’in’, these provide a musical commentary on the fortunes of the hapless suitor. In addition, Robin Maconie composed ‘Come On Into the Sun’ and Kiri Te Kanawa sang the Rossini aria ‘Una voce poco fa’ in a moving sequence to a group of spellbound children in a Rotorua marae. But perhaps the most well-known song – apart from the title track sung by Howard Morrison – was the novelty number ‘Have You Ever Seen? (A Letter Box)’. In this, Gerry Merito, formerly of the Howard Morrison Quartet, puns on various rural and domestic items in a cowshed.

On the 28th January 1966 the NZ Herald announced that filming had begun on the production, which would cost £40,000 and take eight weeks to shoot. Co-investor and star Howard Morrison explained that most of the filming would take place in Rotorua but other scenes would be shot in Tauranga, Wellington, Auckland and Sydney.

Howard Morrison’s character of the undeterred relentlessly optimistic entrepreneur might be an accurate stand-in for John O’Shea himself. Morrison’s optimism, alas, was not indicative of the true conditions under which filming progressed. Even on a minimal budget, the film was a huge risk for O’Shea but he went ahead in the hope that a few “contras” would get them through. The reality was that they were so strapped for cash that O’Shea continued post-production work on commercial jobs while filming on location. At one stage the catering budget ran out and the Morrison family fed the entire crew.

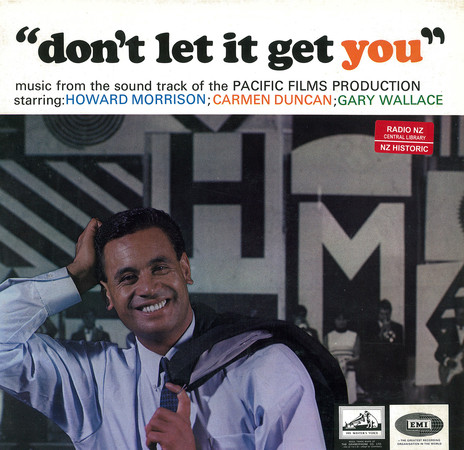

Don't Let It Get You, soundtrack LP - RNZ collection

Williams recalls shooting a complicated three-minute sequence tracking round Howard Morrison singing. “We were literally making the film without a budget ... we had to shoot these complicated musical scenes. We were staying in a motel and at night John was trying to edit documentaries for the Wool Board and the Milk Board so he could pay the motel before we left. When we got to the end of it, we’re still rolling and we’re waiting for John to say: ‘Cut’. Then we turn round and he’s fast asleep.”

One of O’Shea’s ingenious solutions was his premature use of product placements. His use of iconic brands, including Ringamop, the Black and Decker drill and Dulux Paint not only reveals his desperation but also reflects the changing values of the era, following the shift from post war-scarcity to post-war prosperity and the rise of New Zealand’s consumer culture. Some of the most successful scenes were made up as they went along, such as those with Gary the drummer bouncing round amongst a herd of sheep and pretending his drumstick is a flute. The most notorious scene – in which Lew Pryme is driven in a 1950 Jaguar past a Caltex station while a couple of go-go dancers gyrate on the roof – was shot in return for free gas. Tony Williams remembers that at the time, the wind had been blowing Pryme’s hair around so they gave him a liberal coating of hairspray for the shot. Williams: “just as he takes off, a blowfly gets caught in it. No one saw it until it was on the big screen but we had to leave it in: there was no Take Two.”

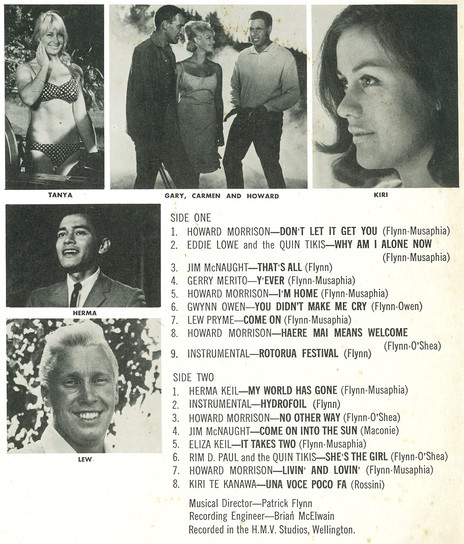

Track listing, Don't Let It Get You LP. - RNZ collection

What the film lacks in polish, it makes up for by providing a showcase for a wealth of eclectic comedic and musical talent. Howard Morrison and Gary Wallace are not only charismatic and talented performers but natural clowns. Their performances – and that of 21-year-old Kiri Te Kanawa, singing to a group of children in an elaborately carved wharenui – are ahead of their time in their awareness of the power of Māori culture.

Utilising existing features of the landscape to stand in for expensive sets becomes less of a deficiency than providing yet another point of difference and a showcase for one of New Zealand’s most popular tourist destinations. The pop culture symbols and props used to liven up the musical segments - showground rides, roller skates, bumper boats and dodgems – would become familiar tropes of music videos in the 1980s.

Don’t Let It Get You may not seem politically subversive by our standards, but it was a determinedly New Zealand film and a much-needed antidote to the tight-lipped repression of post-war New Zealand society. It advocated carefree fun, music and romance and paid homage to local traditions such as Māori showbands.

“NZ Film Has ‘Got Them’” trumpeted the NZ Herald on 19 November 1966, following its Australian release where it was purportedly playing to “packed teenage audiences”. The article quoted Colin Bennett of the Melbourne Age, suggesting, “it could teach the average Hollywood pop picture a thing or two about originality and snap.” Bennett also points out that Australia could boast no equivalent locally produced full-length feature films and that this might cause our Australian filmmakers to, “blush with shame”. Now that the film had been sold to British and Singapore distributors and with extracts scheduled to be shown on American TV, the article revealed that Howard Morrison was currently in Sydney to raise interest in a possible sequel. Morrison defended the film’s low-budget production values by saying “we deliberately made a modest start and we decided to exploit something both New Zealand and Australia have plenty of – top line pop music talent.”

New Zealand critics however were less enthusiastic. After the film’s release, Sunday Times critic Mary Seddon and NZ Listener reviewer Catherine de la Roche both filed scathing reviews, professing surprise that such a clunky plot, shallow stereotypes and embarrassing naïveté came from an intellectual like O’Shea.

But of course, they were not the film’s target audience. Don’t Let It Get You played to appreciative audiences but it was not the box-office smash that O’Shea hoped for. Like Runaway, it left a trail of bills in its wake. Sadly, support from the establishment was notably lacking. The NZBC refused to screen O’Shea’s films: they were “too commercial, and we don’t allow our programmes to be sponsored”. The Film Unit similarly refused to support Pacific’s work, because they were “private enterprise”. Some felt O’Shea was being marginalised in the business world because of his left-wing and pro-Māori sympathies.

Label, Don't Let It Get You LP. - RNZ collection

In retrospect Don’t Let It Get You represents a relatively innocent time when cultural conflicts could be solved by love and the power of music. These messages were replaced by stronger critiques in the 1970s and 80s but once again John O’Shea and his collaborators were at the forefront of the debate.

Excerpt from Don't Let It Get You, 1966

--