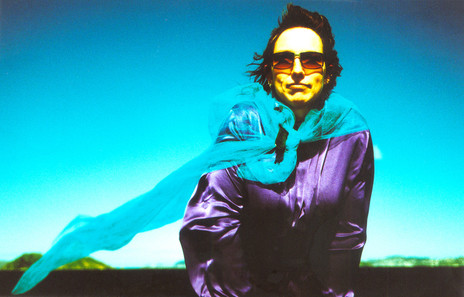

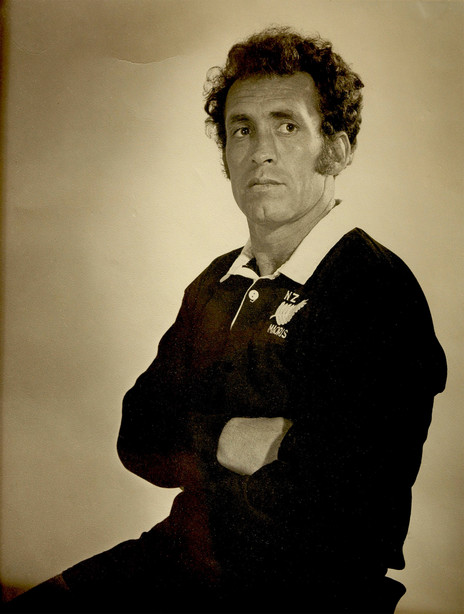

The daughter of a former Māori All Black and a mother who descends from yodelling Bavarian goatherds, and the niece of “New Zealand’s Yodelling Sweetheart”, Fay Charlett, Hinemoana has called Berlin home since being awarded the Creative New Zealand’s Berlin Writer’s Residency in 2015. She was born in Christchurch, in 1968, raised in Whakatāne and Nelson, and lived in Wellington and Kāpiti for over 20 years before leaving for Berlin. In 2024, she returned to Aotearoa to take up the role of 2024 writer-in-residence at Randell Cottage, in central Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

While in Wellington – uncertain just how long she would really stay, in the way of her itinerant soul – she was everywhere. She gave poetry and music performances – reading at a Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Writers on Mondays session, joining a gig with Kahu Kutia and Lee Stuart at the Verb Readers and Writers Festival – and booked a full calendar of individual, free, Poetry Power Hour mentoring sessions with early career poets. She also spoke with the Te Herenga Waka Victoria University poetry students on their folio hand-in day, willingly soliciting their buy-in on the title poem of the collection she was working on, Exhaust World. This gave me plenty of opportunities to have crossed paths with her before she found time to meet for a chat focused on her music, on a blazing blue day in early December.

In the valiant attempt of two poets trying to ring fence talk about music, we tugged on the most enduring thread available to us: Hinemoana’s first musical memories.

Both Hinemoana's parents were good singers: “not professional, but parties, kitchen parties”

“Both of my parents were really good singers,” she says, “not professional, but parties, kitchen parties. My mum’s big sister was Fay Charlett – she was a country singer.” As Fay Doell, she was among the first women to release a record in New Zealand, ‘Texas Star’ b/w ‘Daddy Was a Yodelling Cowboy’, in 1952 on the Tanza label.

“My mother was also a singer, but she didn’t get the confidence that my auntie got. My mother was kind of a bit dominated by her, but they had this really interesting musical relationship in that their voices were just amazing together. I’ve got one recording of them.” (Hear ‘The Three Bells’, sung by the two sisters, on Hinemoana’s Soundcloud.)

“By the time I came along, she was always singing around the house. Actually, that’s how she and my father met. Him and his mates were in the pub, singing songs from some musical, because he loved singing, and she and her friend were there, and kind of flirted together because, yeah, Mum liked this boy, and Dad was a bit of a charmer.”

Hinemoana imagined it was something more than his charisma that attracted her mum to her dad. “It was also just his kind of … survival instincts. He was a really good-looking guy as well.”

She returns to the early music thread. “Voices, parents’ voices, and mum taught me how to harmonise when I was little. So, we would sing together a bit later in her life. She also joined a choir. She was a huge choir fan.” Plus, her mother sang with a Sweet Adelines choir.

“Dad was a music fan as well. He listened to music a lot. He had an old Sony stereo, and I became fascinated with the sound controls at a young age … It was very minimal, and the speakers were massive. I was absolutely enamoured with how you could change the entire feeling of sound with treble and bass. There was a cassette deck. It must have been from the 1970s. We were listening to Louis Armstrong, and he put out one country music album. At the end of that album, there’s the song ‘Miller’s Cave’, about how he – the speaker of the song – found his girl with some other guy and shot them, and then he ran away, and now he’s in Miller’s cave. At the end, there’s this reverb. I was like, ‘Oh, my God, he sounds like he’s in a cave!’ I was really fascinated by that.

“I remember spending a lot of time listening to Dad’s music and also listening to my older sister’s music, when she was still at home. She left home quite young, but she was a child of the 1970s, so she was listening to, like, Deep Purple, Whitesnake. Elton John, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.”

As a teenager, with posters of Boz Scaggs and ABBA’s Arrival on her bedroom walls, Hinemoana discovered Kate Bush – The Kick Inside, and ‘Wuthering Heights’ – and made Spandau Ballet’s Gold her first album purchase. She liked Fun Boy Three, and loved ska, although the latter could be hard to get her hands on in 1980s New Zealand. Her musical world would soon be cracked wide open.

Her musical world was cracked wide open when she met the Hallelujah Picassos

“My best friend Louise’s sister Sue was friends with the boys from the Hallelujah Picassos; they had quite a lot of music. Then I went and lived in London for a year, and then Zimbabwe for a couple of years. The guitar music from southern Africa just blew my mind. When I got back from there and I started studying Māori, then I really discovered the Māori musicians. That was in ’92.”

Although there was a little bit of Māori spoken in Hinemoana’s home when she was growing up, her dad was of the generation where it was not encouraged.

“He wasn’t really the source of te reo in the house. I grew up in Whakatāne, as a kid, and went to St Joseph’s convent school. There was a teacher there called Gwenda Paul – who was the wife of Maanu Paul, the politician, and she was Pākehā – but she taught us Māori. I can’t remember whether we had actual language lessons or whether she just taught us songs. So, that was one of the first sources of the language when I was, like five and six, and then a little bit of the language at high school. But then my parents split and I went to live in Nelson, so that was kind of the end of my te reo anything for a while.”

She went to Canterbury University for a few years, picking up more te reo Māori there. On her return from an overseas sojourn, she completed a degree in Māori and Women’s Studies.

“That’s where I learned the language to the level that I have now, which is still not super-fluent. When I was doing that, I discovered Mahinaarangi Tocker, and Aotearoa, and this band from my own marae, Tauira; they put out a couple of cassettes, and one of their hits was ‘He Māori Ahau’. So, the world of Māori music was amazing, a huge discovery: Dread Beat & Blood, Upper Hutt Posse, Dam Native, Moana and the Moahunters … Then Pacific music too: the Fuemana brothers [Pauly and Phil], Teremoana Rapley … It was amazing.

“My first professional music group was a Māori language trio called Te Hihiri, and it was me, Toni Huata, and Jackie Hemmingsen, and we used to do Māori a capella. We would dress up and do, like, corporate Christmas gigs. It was really fun, but I was terrified because I hadn’t had a lot of performance experience, and Toni did, because she’d done the Whitireia course, and also, she’s Huata! But she believed in me, and it was great. I mean, there’s so much more Māori music available now, it’s awesome.”

there’s so much more Māori music available now, it’s awesome”

When Toni Huata died in February 2025, Hinemoana posted on her Facebook page, “Such a shock, such a loss. Moe mai rā, e te tuahine.”

In 1994 Hinemoana took Bill Manhire’s undergraduate creative writing paper – “it was awesome” – then decided to spend some time making music. “I just got obsessed with singing, and I knew that my voice was something people felt strongly about, and it seemed to do good things in the world. That was one of the reasons I wanted to share it. I felt it had a good effect on people, or lots of different effects on people. At that stage, I was writing songs daily. I was really hungry for exercises like I do with writing now.

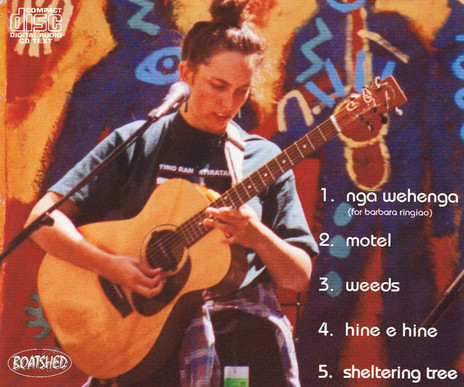

“I’d give myself musical exercises. I was really just drowning in Alanis Morissette at one stage. And so I was, like, could I write a song based on the arrangement and production of one of her songs? I would use models like that. Then I was writing a little bit of Māori as well. I was really, totally in there every day and touring. I was doing gigs at all sorts of places, pubs and cafés, and plenty in Auckland and Wellington, down here. I was helping to run an open mic night for a while down here, so I was really immersed in it. But then, after I did the Masters [at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University’s IIML], I focused more and more on the writing.”

In Te Tau o Te Reo Māori, in 1995 – making a massive 30-year retrospective release due – Hinemoana and a couple of friends formed a production company called Mana Wahine. In partnership with Mangu Kōrero, they made 50 episodes of a programme about Māori and Pacific musicians called Mana Tangata, for NZ On Air. “We made those programmes once a week for student radio. But we made extra copies and sent them out to Māori radio as well. That was one the things I’m most proud of, because we did it on almost no money. I mean, they gave us some grant money, but it was – and I still don’t know if this has happened – the first time there’s ever been a broadcast show which was in both Māori and Pacific languages, across those cultures. And that’s why we called it Mana Tangata, because [tangata/tagata] is a word in Māori and also many Pacific languages. Plus we got to say at the end, ‘Mana Tangata is produced by Mana Wahine’. Which is true on lots of levels!”

Hinemoana stresses the importance of Māori and Pacific not being segregated into separate funding streams, firmly believing they are stronger together, and that they also belong together whakapapa-wise. “It just makes so much sense,” she says.

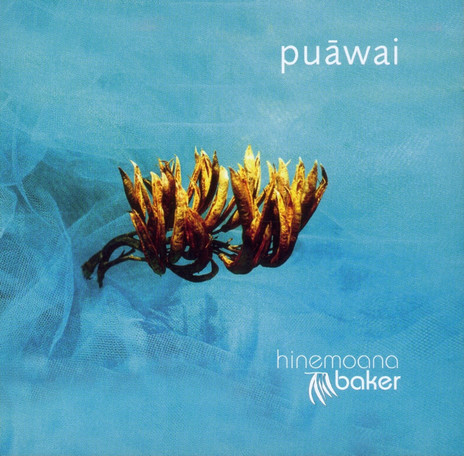

‘Puāwai’ was a finalist for the folk ALbum category of the 2005 NZ Music Awards

She believes it is more her place to document other people’s positions in the history of New Zealand music culture rather than her own. As the whakataukī says: Kāore te kumara e kōrero ana mo tōna ake reka. Nevertheless, we begin to talk about her albums, and approaches to making them, starting with Puāwai in 2004. It was a finalist for the folk category of the 2005 NZ Music Awards, and the title track was a finalist for the Māori language category of the APRA Silver Scroll Award that same year.

“When I was making Puāwai, I was recording it with Robbie Duncan – a legend of the New Zealand music scene – and we were really co-producing it. He wouldn’t say that, but we kind of were. I’m just interested in sound, and what connects my music with my poetry is that I’m sometimes more focused on sound than meaning. I’m not a good enough musician yet to really bring that through; so, my lyrics are still quite, you know, meaningful. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more and more interested in sound, just in itself.

“Even at that stage, when I was making the album, I was interested in John Cage and his exploration of so-called silence as music. So, listening to what’s already around you, and incorporating that was always interesting to me, hence the cicadas.”

One of her tracks credits cicadas to Tāne Mahuta.

“And you know, I remember listening to Robbie Robertson’s album, Music for the Native Americans; there’s one song on there where there’s a, I think, an Ojibwe or Lakota soprano, singing with crickets, which have been slowed down, and the crickets sound like a choir when they’re slowed down. I just really loved that idea of incorporating insects.

“Kate Bush did it a bit too, with one of her albums where she has a dove, or some kind of bird, and she imitates it. That’s the basis of one of the songs. I’m interested in the sound of the world. John Cage says something about how traffic is the ultimate music for him.”

The subject turns to Björk as a kind of field scientist of sound. “I was smashing Björk in those years as well,” enthuses Hinemoana. “These are people I aspire to be more like. What Björk does with her voice, and how she really pushes her voice to do everything, is really interesting to me.”

We talk about Billie Eilish and her brother/collaborator Finneas sampling the crosswalk signal in Sydney – Hinemoana reckons it’s the same sound we hear here – which he later wove into the chorus of her Grammy award winning song ‘Bad Guy’.

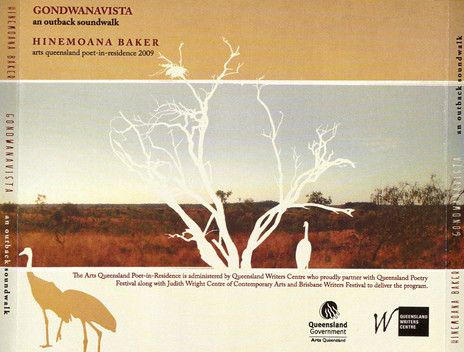

“Using that as a kind of percussion or melodic percussion is cool. And I mean, when I did Gondwanavista, it’s spoken word, but there’s still so much music just in the accent.”

On Gondwanavista: an outback soundwalk (2009), interludes of the voices of tour guides and locals, their footfalls, bird song, flowing water, ominous cattle sounds, machinery and passing vehicles are integral to the sound. There is a monologue about a vertebrae bone of a dinosaur who may or may not have been Matilda, and other monologues about the water supply. Hinemoana converses with a young girl named Amber about the moon, and the conversation is so unaffected, you feel like you are right there with them.

“I was Queensland Arts Council poet-in-residence for three months. Because it was Queensland’s 250th anniversary as a state, they sent us out into the outback on this old 1920s Pullman steam train they’d renovated. Whatever little town we went through, there would be people waving 250th anniversary flags, and there’d be a little morning tea. And one of the things we did was, we went on this tour of this dinosaur museum. At that stage, I was really committed to field recording, and at the end of the residency, they wanted some kind of performance. I knew, right at the beginning, I wanted to do something with field recordings, so I did a live version of that album. I made people listen to it in the dark so they couldn’t just look at me. They had to actually listen. It was really good. I enjoyed it.”

Taniwha was “Hinemoana Baker and Christine White and a Black & Decker workbench”

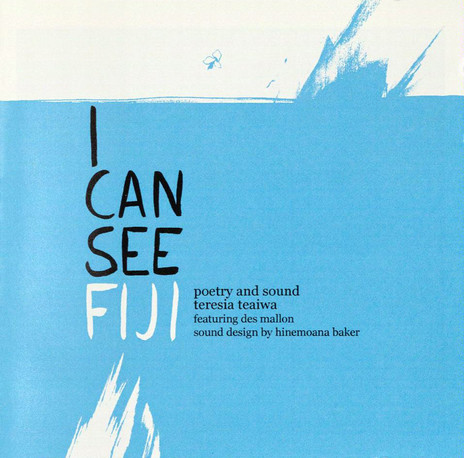

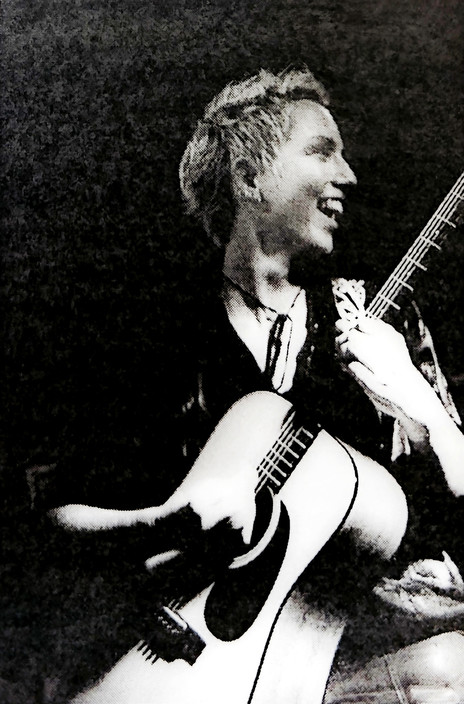

Hinemoana’s other album is Snap Happy, by Taniwha, who were “Hinemoana Baker and Christine White and a Black & Decker workbench, a trio making sweet music with anything and everything they have to hand.” She also produced Teresia Teaiwa’s I Can See Fiji, featuring Des Mallon, describing it as a “docu-story, a poem-entary, even an old-fashioned radio drama.” The project is on Soundcloud. “There’s poetry, for sure, but not as we know it.”

She says her ideal arts pathway would be to explore more sonic art with text on a large scale. “I’ve always had to do things on quite a small scale. I’ve seen a couple of shows in Berlin that are really large-scale sound works that also combine language. I’d really love to be able to do something like that.”

While she says she is not really doing music at present, she can point to a couple of choirs she’s worked with as examples of larger scale work she enjoys being part of.

“The first choir that I was in was 50, 55, voices, and then the one that we created is 20, 25, voices. That’s been amazing. I’m not the choir leader, but it’s been a really interesting musical education. That smaller choir is called Amaryllis for the amaryllis flower. It’s a queer choir, and we sing classical music, and in certain kinds of classical or pre-classical music the amaryllis flower is used as a stand-in for the beloved so that you don’t know which gender that person is, or just so they remain a bit anonymous. Then we found out that the orange amaryllis is sometimes used as a symbol of queer pride.

“It’s been interesting because I don’t read music, don’t read tab, don’t read notes. I can play guitar and stuff, and I learned clarinet for a couple of months at school. But I’m not a sight reader, I’m not a musician. All of my music is self-taught. So, when I get to this choir … I joined during Covid, specifically because I couldn’t do gigs, I couldn’t do anything with anybody, but this choir was practising outside, so it was safe, and it was a community that I could be a part of. Then I’m faced with these very complicated scores and arrangements, in different languages. But I was at that point where I was like, ‘Yeah, I want a bit of a challenge.’ So, I’ve learned a hell of a lot, and I’m a much better sight reader than I used to be, but I still really just read by intervals between the notes. I also rely on the other sopranos around me. I guess when I say I haven’t been doing music, I mean I haven’t been doing much original music for the last nine years, but I’ve been doing a lot of learning and singing communally.”

“I’m not a sight reader, I’m not a musician. All of my music is self-taught”

Tying the thread with a final point about Hinemoana’s magic throat, I ask her how often she’s been compared, vocally, to Joni Mitchell (who can’t read music either).

“I’ve had it said, definitely – and it’s a huge honour to have anyone say that – but I did totally smash her albums, particularly Blue. I could probably sing that note-for-note, like 10 times in a row. So yeah, that was a huge influence.”

Hinemoana didn’t discover Joni until she was touring with Mahinaarangi Tocker’s sister, Mahara, in the mid-1990s. “I had heard Mahinā being compared to Joni, actually,” she says, ever keen to shine a light on someone who is not herself.

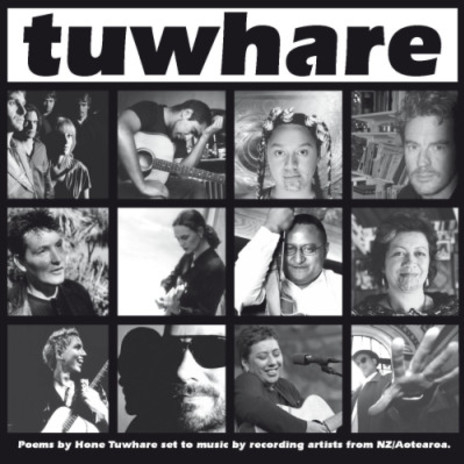

She cites the greatest performance experience of her life to have occurred at the Tuwhare concert, for the poet Hone Tuwhare; Hinemoana contributed the track ‘People Leave I Know’ to. “I was on stage – not at the same time – but with Don McGlashan and Whirimako Black, and Mahinaarangi. Yes, incredible.”

Although Hinemoana is being kept busy by poetry at present, she says she would like to write some more music. “As any guitarist knows, or any instrumentalist knows, it’s not a small decision to bring your instrument with you on a plane, but it can be a bad decision not to! I think what happens for me is that, particularly with music, I need to have this feeling of being a bit grounded, or having some ground under my feet. Yeah, a little bit more stability maybe, in order to make music, and I don’t feel that yet. I’ll have to just let that gently arrive.”