Ozumba settled into the role of producer and frontman, though his experience in music actually went back further. He learnt classical piano from age five and switched to drums at age 11 before taking up guitar and bass a few years later. Unsurprisingly, his background as a drummer meant he took a heavily rhythmic approach to the chugging guitar lines he wrote.

His interest in heavy music partly came through the DIY all-ages gigs he’d attended in his early teens, with influential local bands Mumsdollar, All Left Out, and Cold By Winter arranging their own shows at unlicensed venues such as Ellen Melville Hall, Orange Coronation Hall, and Grey Lynn Library Hall. The all-ages scene had largely ended by the time East of Eden got going, but the band still had the chance to perform at Ellen Melville Hall when they supported US bands Attack Attack! and The Amity Affliction.

East of Eden’s most regular haunt was Zeal in Henderson, which became a home to heavy forms of music in the 2010s. The band had a connection to the Christian music scene, and played in front of their biggest crowds at the Parachute Music Festival. They also supported other visiting hardcore acts and did their own national tours.

At the same time, Ozumba found himself pulled towards other forms of music.

“Towards the end of school, I started diving into hip hop and Afrobeat”

“Towards the end of school, I started diving into hip hop and Afrobeat as part of my exploration of my identity as a Black New Zealander. Afrobeat was definitely something that was played around my house growing up. I slowly began figuring out ways of expressing my unique identity through those kinds of music.”

Ozumba was originally born in Liverpool, where his parents – who had Igbo heritage – emigrated to from Nigeria. He took particular inspiration from rappers such as Blitz the Ambassador and M.anifest, who had come from the African diaspora and kept this central to the hip hop they made.

Ozumba’s first serious attempt at rapping came through leftfield means, via his interest in powerlifting – a form of weightlifting that focuses on heavy squats, bench presses, and dead lifts. He befriended a fellow competitor in Australia who got him rapping publically.

“He was making rap videos to promote powerlifting events,” he says. “One time when I went to see him, he said, ‘you should make a rap with me’. I’d already been recording my own raps, but this was the first time I put a rap out into the public domain. My friend said, ‘you’re really good at this, dude, you should keep doing it!’ So that’s how I ended up actually pursuing it.”

He formed a hip hop covers group called Fleamarket, tried to retain the energy of East of Eden by having a full band onstage with him, and always sought to get the crowd moving. The group only lasted for a year, but it set the stage for the next stage of his development.

Unchained XL

Ozumba moved into writing originals next and took his original rap name, Unchained XL, from a movie he enjoyed as a teenager, Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained. He knew that “Unchained” would be hard to search for online by itself, so added “XL” to make it easier to find. There weren’t many African people within the local rap scene, so he was keen to work with those he did come across – in particular, the rapper Phodiso and singer Ch! Nonso (aka Nuel Nonso), both of whom became his long term collaborators.

He had been developing his skills as a producer since the days of East of Eden. During high school, he initially used the notation software program Sibelius; he was interested in learning composition, and it taught him how to use MIDI instruments. He then upgraded to Adobe Audition – a digital audio workstation or DAW – and finally moved on to another DAW, Logic Pro. It helped that he was now a computer engineer by trade and adept at learning new software, though there was a long process of trial and error as he worked out how to reach a standard he was happy with.

Unchained XL’s first two EPs – Foreign Legacy (2018) and The Migrant Mind (2019) – display a striking mix of hip hop and Afrobeat, with lyrics that reflect the experience of being a part of the African diaspora. Phodiso and Ch! Nonso each appear on a couple of tracks and there are featured appearances by rising star JessB and UK rappers Skunkadelic, Genesis Elijah, Magugu, and Femi. He also released a single that was inspired by local UFC champion Israel Adesanya, ‘Stylebender’.

One of his early breakthroughs came through working with US rapper Kevin Posey.

“Kevin was dating someone from New Zealand,” he says, “so he was here for a couple of years. He’s a talented producer and rapper, so we just clicked and started making music together. We were both at an interesting time of our lives, reflecting on where our careers might go next. That’s where the song ‘Letter to My Future Self’ came from.”

He was wary of pigeonholing himself as “this diaspora African kid working out his identity”

The personal nature of the track connected with audiences, despite being quite different from Ozumba’s previous work. This fed into his feeling that he pigeonholed himself in his early years.

“My work as Unchained XL was always branded as coming from this diaspora African kid who is working out his identity and really wants to showcase it. So not only would I use a lot of Afrobeat sounds and take influence from Fela Kuti, I’d also wear a lot of Ankara prints and Nigerian jewellery. As I got a little older, I realised that being secure in who I was meant not having to wear my identity on my sleeve all the time …

“The other big thing was my daughter being born, in January 2020. I had new music coming out and had started to move away from Afrobeat hip hop, so I decided it was a good time to change my name. I had a lot of people telling me not to do it and, to be honest, it was only a few years later that I really became aware of how much I’d had to start over from scratch.”

The birth of Mazbou Q

The name Mazbou came from an anagram of his surname, Ozumba. Another reason for choosing the moniker Mazbou Q was that it sounded like the name of a specific person, which seemed more appropriate for making tracks that expressed a personal viewpoint rather than the largely political lyrics he’d written as Unchained XL.

‘To The Gates’, the lead single of his 2020 EP Afroternity, reflected his new approach.

“That track was very introspective, vulnerable, and emotional. It wasn’t about politics and it wasn’t a confidence flex. It was a very personal song, a very deep song. It was reflected in the music video, which is very symbolic of working through personal changes and hurtful events. Sonically, it just sounds different too. I’m really singing on that song and there’s layers of backing vocals, which show some gospel influences coming through. There’s a rock aspect too. So it’s really me embracing a lot more of my musical background.”

The song was combined with an eerie music video that alternated between a crime scene, a person dying in a hospital bed, and Mazbou in a church filled with blindfolded parishioners. It was made by the Umbrella Creative; Mazbou had a long connection with their main director.

“I knew Swap Gomez from Umbrella Creative since way back in the Myspace days in the mid-2000s. He was a drummer and, at that time, being a drummer was central to my identity too. When I later heard that he was doing film work, we reconnected again.”

Mazbou continued to present pro-Black messages, arguing for “focusing on positivity in any given situation” on ‘Bad Energy feat Kevin Posey’ and he created an upbeat collaborative anthem with ‘Blacklight feat Mo Muse and Phodiso’.

Mazbou Q expanded his sound even further on his 2021 album The Future Was. The thumping horn-driven groove of ‘Beat Up, Bullied and Dunked On’ sounded like classic hip hop, with punchy rapping from Mazbou and Vallé, as well as turntable cuts from Scizzorhands. When Mazbou heard a drum fill that he loved from Wellington jazz star Myele Manzanza, he managed to clear it for a sample and created the funked up track ‘Just Let It Go’ which also featured his old friend Phodiso, rapper Tyler Trench, singer Fae, and a trumpet solo by Loz Coz. He also hooked up with another rising star from the African community of Aotearoa, getting Raiza Biza to guest on ‘G.O.A.T. Problems’.

By this stage Mazbou had a regular live band and wrote many of the tracks on the album with live performance in mind. He also decided to push the visual side of the work by expanding on the theme of his track, ‘Don’t Stop Regardless’. The lyrics imagined a time traveller coming back from a future in which Africa has become prosperous and united, so he wants to encourage young people from the global African community to reach towards that goal.

The Umbrella Creative helped him create a short, partially fictional documentary that was inspired by the track.

“At that time, NZ On Air had expanded their funding so you could do more than just a music video. So I thought, ‘why don’t we do a mini-documentary that captures the essence of the song?’”

The documentary portrayed a range of young African creatives and then had the time traveller opening out their vision of what might be possible in their careers.

This wasn’t the only way that Mazbou used collaboration as a way to push into new areas. He always kept an open mind when working with other musical acts. His EP with Jessie Booth saw him move into R&B-infused beats with gentle, almost-jazzy guitar lines; he turned towards much heavier, cinematic beats for the Metahuman EP he did with Missouri rapper xJ-Will, which was recorded during a trip to the US. Perhaps one of his most surprising tracks was ‘Bruised Soles’, which put blues guitar over a thumping beat.

“I’ve always seen collaborations as an excuse for me to break from my brand a little bit”

He enjoyed the freedom inherent in these projects.

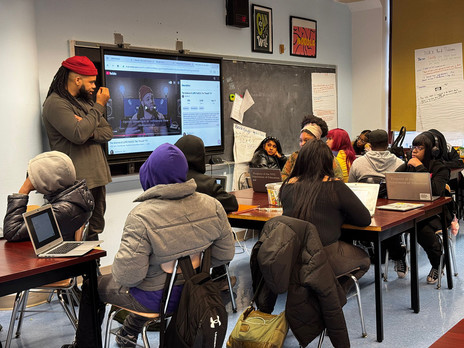

“I’ve always seen collaborations as an excuse for me to break from my brand a little bit. If I know a person is into a style and I have a low-key interest in it as well, then I feel more free to go in that direction. Though it was funny in the case of ‘Bruised Soles’ because I did that with Regi Angelou, who is very much a New York rapper. I sent her the track and she was, ‘oh, I was not expecting this, but I’ll do it anyway!’ So that’s just an example of me thinking, ‘well, since I’ve got someone else on the track, let’s just try something new.’ I do a lot of music mentoring with young people, and I’m always trying to get them to do something a little bit different, or go into an area.”

Mazbou Q was a well-known presence on the local rap scene by this stage. Nonetheless he sometimes felt like an outsider, given that rap in Aotearoa was so dominated by Māori and Polynesian artists. It was uncomfortable to hear local rappers thoughtlessly spit the “N” word or claim an ownership of hip hop that seemed to discount the African roots of the culture. These concerns were magnified by the Black Lives Matter protests in the US and he commented online about some of the blindspots of the local scene, which made for some tense exchanges.

The issue came up again a few years later, when Mazbou saw the line-up of the first Eden Fest event.

“They had a bunch of international black headliners, including Nigerian headliners, but not a single local Black opener was on that festival line-up. So I put up a post saying, hey, look, this is not good enough, because what if that happened the other way around? What if a community of Black people here put on an event and invited some of the biggest Pacifika names from around the world – like The Rock and Jason Momoa – but no local Polynesians were involved or even consulted? Would that not be crazy? It’s frustrating that people don’t look at Black music and Black culture the same way they look at other cultures. So that was the conversation I was sparking up. The problem was that I got hella backlash and people saying I was jealous or that I didn’t work hard enough or that it was about business not race. They were all the same things that white culture has said to brown culture before to account for why they weren’t getting the same opportunities.”

Mazbou was pleased when Eden Fest subsequently added Raiza Biza to the line-up and the following year Jujulipps performed. The downside was that Mazbou himself felt as if he’d provoked the ire of some people within the local rap community. In the meantime, he created a new avenue for reaching listeners worldwide.

The Rap Scientist

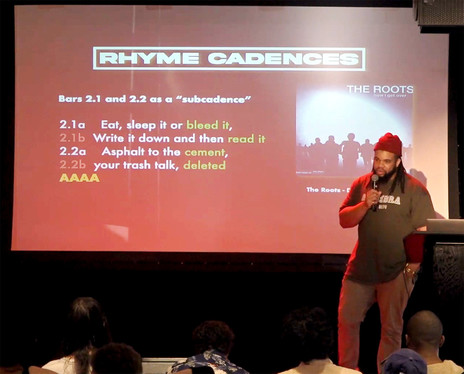

Mazbou Q’s breakout as viral-clip-producing online educator first came through a TikTok video in which he advised aspiring rappers, “don’t rap on beat, rap behind the beat.” This encouraged him to do more short clips on the fundamentals of rap flow and he soon grew an impressive audience. It might have seemed like a sudden change of direction but it flowed on smoothly from the experience he had built up throughout his involvement in music.

One obvious element that went into his success was that his mother had been a teacher, and he had a sense of what it took to communicate ideas clearly. His first attempt at making an online video tutorial was during his time in East of Eden. He made a YouTube clip that explained how guitarists could create more interesting guitar lines by moving their riffs back a couple of beats or mixing them up with bends and runs. He later noticed that one of his short rap tutorials was very similar: it described moving the placement of a line of rapping back a couple of bars to create a more interesting rhythmic interplay with the beat.

However, his first attempts at creating video content as a sideline to his rap career involved him “re-imagining” local songs – remaking them from scratch in his home studio and filming the process. It often involved completely changing the style of the song – for example, by turning ‘Soaked’ by Benee into a rap track.

Realising that shorter slices of content would be required to fit the TikTok format, he turned his attention to the fundamentals of rhythm within rapping. Part of his unique ability to break down the fundamentals of how raps sit on a beat extended back to his formative years as drummer, though he also credits his professional studies.

In his online tutorials he turned his attention to the fundamentals of rhythm within rapping

“I did Computer Systems Engineering at university and it took me a while to realise how much that mindset played into how I understand the process of making music. Engineering is all about understanding the first principles of a system – how the system is made up of components, which work together to turn a certain input into a certain output. That’s also how I look at rhythm. The reason why people love my clips is because I’m breaking down what seems like a complex or tough to understand rhythm into first principles. Then I build it up from there. People might not understand all these crazy ideas, but they can understand the click: one-two-three-four. Then they can see how I subdivide the click and get to something complex. All of a sudden, people get what’s going on.”

Mazbou put an immense amount of work into improving his videos, gradually teaching himself advanced video editing skills, lighting, and computer animation; many of his videos have visual breakdowns of rhythms at work.

He realised that TikTok might have worked for gaining a new audience, but it was more difficult to get those viewers interested in his music or wider work because his TikTok videos often just appeared within a stream of content, rather than viewers following him or seeking it out. He worked to develop a following on Instagram and YouTube as well, at which point he began to gain serious interest from overseas. He was later stunned to find himself being followed by hip hop luminaries such as Lupe Fiasco and Joey Bada$$, as well as renowned music prodigy Jacob Collier.

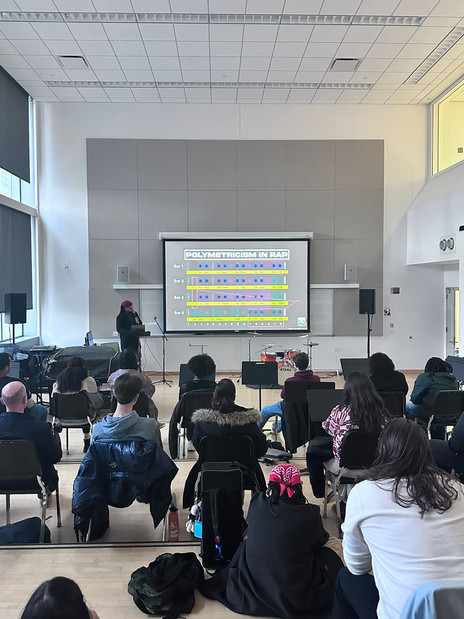

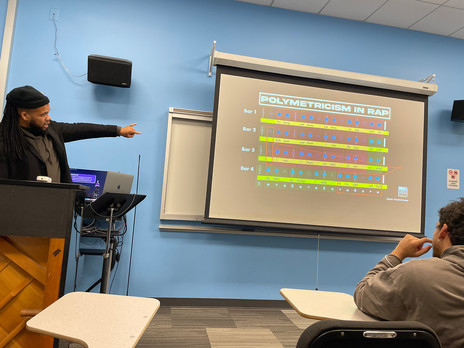

He also received messages from lecturers at universities in the US who noticed what he had been doing and wanted him to speak to their classes. It led to his Rap Science trip to the US in 2023, which included talks at Louisiana State University, Southern University (in Baton Rouge), Harvard and Berklee. He was required to make an hour-long presentation from the material he ha put on social media, but he relished the opportunity to get further into music theory and rap flow. The following year, he did two trips: returning on the first trip to Berklee and speaking at the Hip Hop Congress’s annual meeting. He next visited New York, where he spoke at NYU and Borough of Manhattan Community College.

Mazbou continued to develop this side of his music career by creating an online tutorial that viewers could pay to access for a more in-depth lesson on how to incorporate his ideas into their music. However, it was a trickier process working out how to get this new audience interested in his own music …

Bringing the science to Mazbou Q

Mazbou Q continued to release new music over this time. His 2023 album The Sum of Unfinished Business was released song by song, so that listeners had a chance to check out each track in turn. The collection had elements that tied it back to his earlier work. One of the standout tracks from his Unchained XL days – ‘E No Dey Easy’ – was given a full spectrum re-work, though still featured old friends Phodiso and Ch! Nonso. He also provided the latest in an ongoing series by dropping ‘Weight On My Bars Pt. 6’.

However, the album looked forward as well as back. A track like ‘Now I’m Whole’ had all the attitude of a hardcore rock track, but done over a grinding synth line instead. There were also hints of how his sideline as the Rap Scientist might provide a boost to his own music. ‘CLRS’ was a call for unity amongst people of African heritage across the world. It had a guest spot by King Green, a US rapper who had previously performed with Pharrell Williams and Eminem. While on his Rap Science tour, Mazbou was able to meet up with King Green in Washington DC and film a video for the track.

In 2024 Mazbou was just in the process of starting on a new run of songs when a song he had largely forgotten about suddenly gained traction.

“someone messaged me to say, ‘yo, your song ‘In My Bag’ is going crazy’ ”

“I do a lot of sync work on the side – top lining and or composing for brands and so on. I was approached by a representative from Meta [owners of Facebook and Instagram]. They needed some more music for their music library, so people can use it as background music on their content. I wrote a bunch of tracks in a rush: quite throwaway stuff. But once they went live, someone messaged me to say, ‘yo, your song ‘In My Bag’ is going crazy’. I looked it up and found it had 100,000 uses on Reels. I hadn’t really been paying attention, but it turned out I had a bunch of hidden messages asking me to put ‘In My Bag’ on the streaming sites. The problem was, I’d sold the rights to Meta so I couldn’t use the original master recording. I had to do a Taylor Swift and re-record my own song from scratch. If you listen to the version on Facebook and Instagram, then it’s actually slightly different. I released it with no promo and it ended up being my biggest streaming song. I don’t even like it that much, because I literally wrote it in a couple of hours.”

Mazbou’s main focus over this time was trying to find a way to use his Rap Scientist following to gain more listeners for his own music.

“I had two distinct brands and needed to unite them. ‘Polymers’ was the first song I wrote where I put aside any thought about what might work on playlists or radio. Instead, I just wrote a track that packed in all these different complex rhythmic techniques that I teach about. Then I was able to create content about those techniques and use the song. One of those videos ended up blowing up, with around two million views on each platform. That helped catapult that song on streaming too. It was really an experiment, but it worked so I kept making songs like that. I tied them all to a science theme, that’s why the titles were based on scientific fields: ‘Physiology’, ‘Photonics’, ‘Cryptography’ and so on. Most of the songs aren’t actually about the subject mentioned in the title – they just use the word in there. I was just playing on the idea of being a rap scientist. Each one of them had a rhythmic technique that I was trying to teach people. On ‘Physiology’ you’ll hear polymeter, on Cryptography you’ll hear progressive swing. That was the main idea.”

Fortunately, he found that having this restriction on his songwriting process actually helped stir his creativity and sent him in unexpected directions. For example, he came up with the name “Torque” for one track and figured that it might be fun to use the pun of “talk” as an inspiration to do some real talk on the track. This led him to dig deep and he even touched on his recent diagnosis as having ADHD.

“I just had some Ritalin pills issued, now I’m tranquil / grieving the life I could’ve had. Damn! / Wait a minute, you neuro-typicals never told me how badly it slaps to not have to procrastinate or lapse into distraction / scrolling screens to overdose on dopamine just to manage thoughts.”

In this way, Mazbou has been able to fuse his role as rapper and educator, while still opening up a space that allows him to express himself and this leaves him excited for what might come next.

“‘Torque’ was a big turning point for me. That song still has the rhythmic techniques in there, but the heart of the song is how I was feeling. The fact I was struggling with my music career and my ADHD diagnosis. Amazingly, someone actually pointed out to me that torque is a type of force that comes from the edge of what is being turned – it’s never coming from the inside. So that could also be a metaphor about my own feelings about being a Black New Zealander. I’ve been deeply connected to the culture of hip hop, while always feeling like an outsider. I never expected anyone to pick up a detail like that, but people did. That showed me that I can still use the rap science approach, but give myself more leeway to express myself more holistically.”