Parachute Festival, Mystery Creek, Waikato. - Parachute Music Collection

Parachute Festival was one of the largest local music festivals in the first decade of the 2000s. It relied heavily on Christian contemporary music and included every imaginable genre from hip hop to hardcore punk. It allowed rising pop stars including Brooke Fraser and Kimbra to perform in front of huge crowds, while helping to mint international success stories of its own, through acts such as The Parachute Band and Rapture Ruckus.

The “Parachute Arts Trust” was founded in 1989 without such lofty aims in mind. Founders Mark de Jong and his wife Christine (Chris) de Jong were both musicians – Mark a bass player, Christine a keyboardist and singer. Mark had been playing in church bands since he was 14 years old, but was frustrated by the chasm between “Christian music” and the wider music scene.

Mark de Jong in the early 2000s. - Parachute Music Collection

“The message we wanted to send was that there shouldn’t be these restrictions on Christian music,” he says. “We happen to be Christian and we’re making music, but that shouldn’t limit what the music is. At that time, if you were a Christian musician, there was definitely a stigma and you didn’t get the same opportunities in the music industry. At the same time, people in the church were concerned that secular music was evil and might draw listeners towards sin. We just thought ‘that doesn’t make sense!’ Sure, people can use music or any art form – whether film or literature - to spread bad messages, but music is inherently neutral. So we felt there were some ideas that needed to be challenged.”

Mark co-founded the Mainstage music festival in 1987 and the event was still running when Parachute Music was launched, so the idea was for it to run alongside it, supporting musicians by arranging band nights and get-togethers.

First Mainstage Festival. - Parachute Music Collection

However, following the third and final Mainstage event, Mark believed it was time for Parachute to run its own event.

The first Parachute Festival in 1992 drew 1200 people to El Rancho Christian Holiday Camp in Waikanae, 60km north of Wellington. The venue had three auditoriums, each with an in-built sound system, and these became separate stages for the festival. It was already set up for camping, and suited the three-day event they were planning. Mark called on existing groups from within the Christian music scene, such as long-running group The Lads.

The festival grew steadily over its first three years, partly buoyed by the rising popularity of “Christian Contemporary Music” (CCM). The local Christian radio station Rhema reacted to this overseas movement by creating a new, youth-orientated station, Life FM.

It seemed like a good time to expand the size of the Parachute Festival by taking it to a new location, the Totara Springs Christian Centre in Matamata. This would mean that it was now an easy drive from the big population centres in the top half of the North Island.

Festival-goers chilling at their campsite at Parachute Festival c.1997-98. - Alice Casserly

American rap-rock band DC Talk led the charge from the CCM world into mainstream charts with their album Free At Last (1992) creeping towards platinum status in the US. They were booked to headline the 1995 Parachute Festival but on the morning before their evening performance, the festival grounds were inundated with pouring rain. The move to the bigger location meant that the organisers needed to construct outdoor stages. Unfortunately, the tarpaulins rigged over the main stage were not enough to defend against the downpour and water dripped down onto the electrical cables below.

DC Talk’s tour manager arrived onsite and said that he couldn’t let the band perform in such conditions. Mark wasn’t sure what this might mean for the festival – if the headliners didn’t perform, would people demand their money back?

A couple of hours later, the band themselves arrived at Totara Springs and band leader, Toby McKeehan (aka TobyMac) reassured Mark that whatever happened, the band would find a way to perform. In the end, the rain eased and the festival was able to go ahead as planned, though Mark can still recall the stress of that afternoon.

“It was frightening,” he says. “I’m 64 years old now, but I can still feel the emotion that I felt on that day, 30 years ago. We’d already gone from 1200 people to 2500 people in three years at Waikanae and now we’d doubled that capacity to 5000. We’d taken another huge step by getting DC Talk. That was my first time interfacing with the CCM world in America, which was a lot more sophisticated and business-oriented than I had expected. So that was difficult enough. Then to see it potentially blowing up in my face. I just wanted the ground to swallow me up! But it’s those lows that can turn into the biggest highs. To look out that night and see the bowl of this new venue filled with people, going crazy to this unbelievable band, who were just nailing it – it was incredible.”

Festival-goers Parachute Festival with musician Chris Lamsam (middle) c.1997-98, a few years before he co-founded children's musical supergroup The Funky Monkeys. - Alice Casserly

The following year, the festival caught another overseas group on the rise, and this one had a local connection. Back in the late-90s, local funk-rockers Drinkwater had done a reasonable job of straddling the worlds of both Christian and alternative rock. Lead singer Phil Urry certainly cut a striking figure with his wild curly blonde locks and charismatic stage persona, but Drinkwater were already nearing their end by the time they supported US/Australian group The Newsboys in 1994. Six months after this show, the headliners contacted Urry to ask if he’d be keen to join them on bass – despite being a guitarist – and he signed up. He found Americans struggled to pronounce his last name so switched it with his middle name, becoming Phil Joel.

Mark knew Urry from the early days and so was keen to work with the Newsboys. “We brought the Newsboys over to do a concert in Wellington, but no one came. It was another of those emotional moments where I questioned what I was doing! There were just 15 people in this massive school auditorium. It was embarrassing. But the Newsboys performed like it was a sold-out auditorium. They were getting pretty big overseas, so we brought them over for Parachute Festival.”

The Newsboys first performed in 1996, then returned in subsequent years; Urry even re-formed Drinkwater for a one-off performance at the festival in 2001.

Delirious? at Parachute Festival, 2006. - Parachute Music Collection

Gradually, Parachute Festival gained a reputation globally as a major Christian festival and this gave them more access to big name artists.

“Getting the UK group called Delirious? was one of our biggest coups,” says Mark. “Their music had elements of worship, but they were just a fantastic band essentially. I happened to be at this conference in Nashville and went to the bathroom. I ended up standing next to their manager. One of us made a joke and then we got chatting afterwards, partly just marvelling that there we were – a British guy and a Kiwi – deep in the heart of America. Later on, when we visited London as a family, we went to see them play and they agreed to come out to New Zealand. Few people realised how good they were at that stage, but their performance ended up being one of the best that we ever had.”

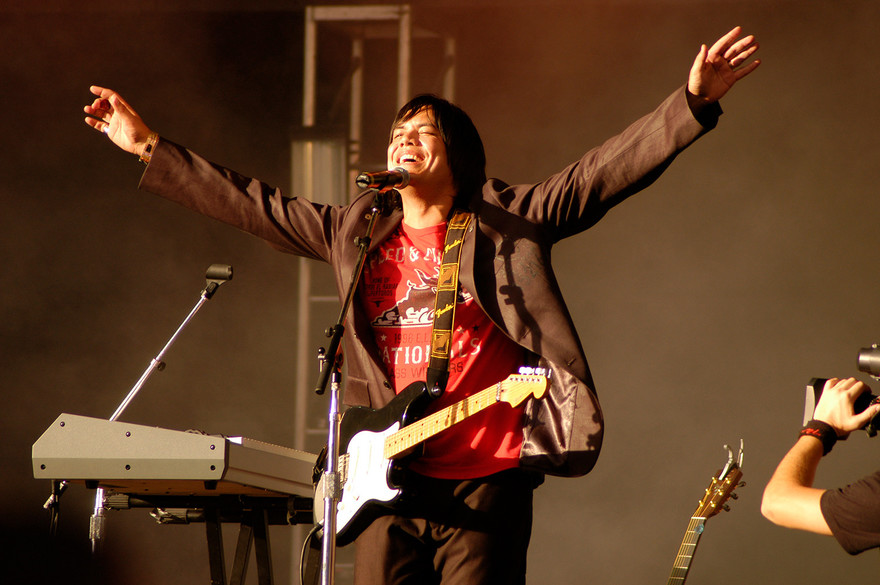

Wayne Huirua from the Parachute Band original line up. - Parachute Music Collection

Delirious? not only took to the main stage Parachute in 1999, but provided a crucial connection for The Parachute Band, the festival’s resident group. Mark and Chris had originally formed the group to fill a gap in the programming.

“We needed a band to play at the morning services, so Chris and I got some musicians together. It just seemed nice to start the day with a homegrown act. Some of the people in the group started writing songs and we were offered other songs by friends, but then people started asking, ‘where can we get these songs?’ So we ended up in Revolver Studios recording the first album. Eventually the band started to take off internationally. What started as a little side project became quite an undertaking. We had two young kids – Sam and Jane – so we had to take them touring the world with us. Every year we also had this deadline of late January coming up, because the festival had to be ready to go. It was just a crazy busy time.”

Amazing, an album by The Parachute Band, showing Wayne Huirua, Chris de Jong and Kelly Bennett (Worship Extreme/ Parachute Music, 2002).

The Parachute Band’s fifth and sixth albums Amazing (2002) and Glorious (2003) gained a remarkable reach through a deal they had with Fierce! Distribution, a company that Delirious? had created to put out their own music. Chris continued to be one of the key songwriters/ vocalists on songs including ‘You’re My Lord’, though other enduring tracks were sung/ co-written by Andrew Ulugia (‘Complete’ and ‘All The Earth’) and Louis Collins (‘I Stand In Awe’). Their live album All The Earth (2006) reached No.12 on Billboard’s Top Christian Album charts.

Remarkably, this was all taking place just as Parachute Festival was becoming one of the biggest music festivals in New Zealand. By the early 2000s, Parachute Festival was drawing over 10,000 attendees and had nearly two dozen full-time staff. In 2004, the festival moved to a new location so it could accommodate its continued growth, taking over the Mystery Creek Events near Hamilton. The numbers continued to climb, eventually surpassing 20,000 people.

For many, the appeal of the event was that it banned alcohol and drugs. Teens could get their first experience of a music festival while their parents felt reassured they were in a safe environment. Certainly there were always a few rule-breakers who took it as a challenge to get wasted at the Christian festival, but for the most part the revellers were high on music, religion, or energy drinks. There were four to five stages with over 150 bands, a food area with dozens of options, and a range of amusement rides.

Parachute Festival, 2008. - Parachute Music Collection

Parachute Festival reached 27,000 attendees in 2007. The event now had more people working or volunteering on site than the numbers of attendees at its first year. The organisation was also able to raise money for other causes, such as helping to sponsor a village in Rwanda through World Vision, and in the final years they offered “pay what you can afford” tickets for families who couldn’t come up with the rising ticket prices.

The festival’s growth meant that Mark and his team were basically overseeing an entire town’s worth of people and it came with an incredible level of stress, especially when things went wrong. Two examples: in 2007, a young man who’d been helping at the festival went to swim at a nearby section of the Waikato river and drowned after jumping from Narrows Bridge; in 2013, the bass player for Great North, Rachel Donnell, was hit by a poorly secured metal chandelier with dangling glass bottles, which fell from overhead while she was in the food area. She was left with a traumatic brain injury, had to take three months off work, and was limited to working part-time for a year afterwards.

Events like these were heartbreaking, but Mark had to try to take them in his stride to keep the festival going.

“I remember that death in particular. It wasn’t within our gates, but that didn’t really change anything. It felt very personal. The guy made an unfortunate decision but lots of other people had been doing the same thing, jumping off that same bridge. It was definitely a very heavy thing to have to face. Things like that are bound to happen when you have that many people, but do they affect you? Of course they do.”

Parachute Festival 2009

The scale of the festival meant it could provide a tremendous boost for young musicians, who were able to play in front of large, receptive crowds early in their careers. This was certainly the case for Steriogram, who formed to play the festival in 1999, and Kimbra, who appeared in 2008, three years before she finally had a solo hit.

Perhaps the most impressive success story was Brooke Fraser.

“When she was recording her first album,” says Mark, “she had a job as our communications person. She wrote a lot of our publicity material and she was very clever at it – she had a great way with words. It was fabulous to be part of her journey and then to watch her career take off. That’s what we wanted Parachute to be about – to help musicians succeed in that way.”

Two months after Fraser’s debut album What To Do With Daylight (2004) hit No.1, she performed on Parachute’s main stage, though it was actually the fifth time she had appeared at the event.

Other rising acts used the festival as a springboard for connecting with the Christian music scene overseas. The rapper Rapture Ruckus (Brad Dring) broke the record for CD sales at the festival when he promoted his self-titled debut album with a set in 2002. His next full-length release was a live CD/DVD recorded at the event in 2008, before he signed to US label BEC Recordings and relocated to Nashville.

Dave Dobbyn performing at Parachute Festival, 2007. - Parachute Music Collection

The festival also provided an opportunity for established musical stars – such as Dave Dobbyn and Stan Walker – to be able to express their Christianity onstage rather than keep it low key as they would in front of a secular audience.

The Parachute Band re-emerged with a new line-up which included Mark and Chris’s son Sam de Jong as the drummer. They toured internationally and released four albums, two of which won best gospel/ Christian album at the Vodafone New Zealand Music Awards, and they won the people’s choice category at the 2008 awards. Sam went on to be a producer and songwriter based in the US; his co-writes include the Gracie Abrams hit ‘Close To You’, which has over half-a-billion streams.

Ruby Frost aka Jane de Jong at Parachute Festival with the logo of the White Elephant stage visible behind her. This is where the indie bands commonly appeared. - Gareth Shute

The de Jong’s daughter Jane was also a musician, under the name Ruby Frost. She performed a few times at Parachute Festival and was supportive of Parachute Band, even supplying a couple of songs for the group. However, she was bemused by the CCM acts out of the US who came across like soundalike versions of popular secular acts and she took her own career in a different direction.

“I feel grateful to have grown up in such a rich musical environment,” says Jane, “standing side-of-stage as a kid watching incredible performers doing their thing, and watching my parents in the studio. But I do remember going to a CCM conference in Nashville when I was about 13 or 14, and seeing the machine of the industry behind a lot of these bands when CCM was at its peak. I guess I realised that wasn’t really a world I felt I wanted to be part of. I understood the Gospel, or spiritual, music there; but some of the CCM music just felt like Christian versions of popular music, which was fascinating to me. I don’t think my music has ever been very suited to that world, and I decided to just do my own thing when it was time to record my first EP.”

Ruby Frost at Parachute Festival, 2013. - Parachute Music Collection

In 2010, both Mark and Christine received the Queens Service Medal for “services to music”. However, as time went on, Mark felt more restricted in how he could run the festival. The event had always been non-denominational, so it had a relationship with churches from across the spectrum of Christian belief but – as the event grew – some groups wanted to have more input. Mark felt things being pulled in an increasingly conservative direction, which pulled it away from its core aims.

“When we started Parachute,” he says, “we weren’t trying to proselytise. Our aim was to change the thinking of the church about music. As the festival developed, it included opportunities for people to learn about Christianity and I was okay with that. However I was never comfortable with the idea of using the emotional high of music to convert people, as if you were saying – this is what heaven will feel like!”

After years of trying to pull down barriers between Christian musicians and the secular music industry, he felt pressure to start putting them back up. A case in point was the inclusion of hardcore acts like East of Eden (one of Mazbou Q’s early bands), which were only accepted with provisos.

“The local Christian community accepted our argument that certain musical styles aren’t good or evil,” says Mark. “Heavier types of music were okay, but we now we were being told that those bands had to be ‘real Christians’. They had to not have sex outside of marriage, not be gay, not use drugs. Only then were they allowed to play whatever music they liked. I always tried to argue, life’s not that black and white!”

When the festival booked Nesian Mystik in 2007 and Elemeno P in 2011, there were complaints that not all the members of each group were Christian, despite the fact that Nesian Mystik’s Feleti Strickson Pua was the son of a reverend, while Elemeno P’s drummer Scotty Pearson had been in one of the first New Zealand groups to break into the CCM scene in the US, Hoi Polloi.

Mark felt there was a clear value in having a mix of artists – from hitmakers such us Avalanche City and Evermore through to rising stars like Ginny Blackmore and Vince Harder and foundational figures in the local Christian music scene such as Derek Lind and Steve Apirana.

The festival certainly pulled in some heavyweight acts in its heyday, most notably in 2008 when it hosted both Leigh Nash from Sixpence None The Richer (their song ‘Kiss Me’ went to No.2 in the US) and the crossover act, Switchfoot. However when Switchfoot returned in two subsequent years, it was a sure sign of a line-up that was getting stale.

Mark became increasingly frustrated with how the festival was failing to keep up with the mood of the time.

“I remember explaining the situation to the Parachute board of trustees,” he says. “There used to be a time when a Christian kid growing up in a Christian home would listen to Christian music and have the radio tuned mostly to Life FM, but there was a demographic shift happening. Kids now listened to whatever they wanted. If we couldn’t even get acts that had Christian members, but who didn’t play within the Christian music scene then the whole thing was doomed. A lot of acts were already wary of playing a Christian festival, so by placing more demands on them, you’re losing the best, the newest, the most exciting artists.”

Adeaze on the main stage at Parachute Festival. - Gareth Shute

By 2014, there was a lot more competition when it came to local music festivals, with over half-a-dozen running in the North Island. That year, Parachute Festival posted a half-a-million dollar loss. Mark had a clarifying discussion with Parachute’s board chair Martyn Norrie at the end of that weekend.

“Martyn responded to my concerns – ‘you know you don’t have to keep doing this?’ That was when we started moving towards closing it down. We wanted to do one final year as a farewell, given it would’ve been the 25th year of the event but came to the conclusion it wasn’t worth it. It could’ve been a disaster, who knows? … We also talked about scaling back the festival, but once you’ve done a big, iconic event, then part of its power is its size. I didn’t think it would work to make it drastically smaller. You risk tarnishing the reputation you’ve built up.”

In the years that followed, Parachute Music re-focused itself on supporting musicians, no matter what their religious beliefs. The organisation set up a studio which it funded through charitable fundraising and doing commercial work (such as recording all the music for TV shows such as Dancing With The Stars). Its main hub now contains a dozen studio spaces, it also offers wellbeing services and discounted studio spaces to creatives working in the music industry.

Mark looks back on Parachute Festival fondly, but sees it as a closed chapter.

“I felt like we achieved what we’d set out to achieve and, by the end, it felt like we were creating a monument to the status quo rather than anything new. We risked becoming part of the problem, not part of the answer. I talked with my wife after it ended and she categorised it perfectly ‘we really need to be back out on the edge, trying to create change. We just want to help musicians take the next step on their journey.’”

--

Link: Documentary on first Mainstage event, featuring Mark de Jong, Steve Apirana, Derek Lind, Stephen Bell-Booth, Guy Wishart, and Jamboree, who would later re-name themselves Hoi Polloi and gain international success.