Before the record store “World” section there was the “International” section, wedged down the back of the shop between Spoken Word and Orchs & Pops. It’s the place where I first realised the prevailing narrative of western rock and roll was only one thread in a wide tapestry of musical stories.

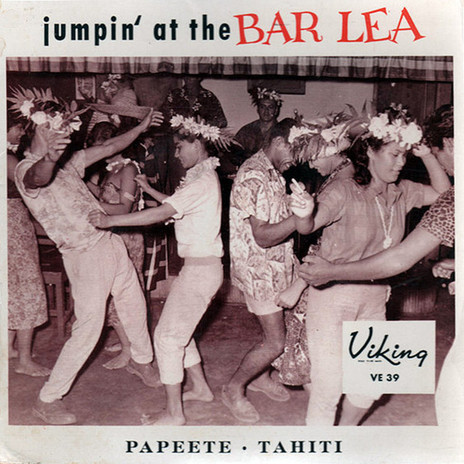

Eddie Lund And The Bar Lea Orchestra - Jumpin' at the Bar Lea EP (Viking, 1959)

Codified in 1987 by the North American record industry, the World genre was a well-intentioned attempt to give writers and performers from other lands their fair dues. David Byrne’s 1989 Brazil Classics 1: Beleza Tropical was a game changer. The compilation of archive material coincided with the rapid uptake of the compact disc and it surprised Sire Records by flying off the shelves.

Byrne and his team created a curatorial template of sorts: stylish packaging, contextualising essays, lyric translations and, most importantly, great sound from the original Brazilian master tapes.

Other record companies took note and soon their tape inventories were being excavated for forgotten foreign titles. Through the 1990s and 2000s labels such as Analog Africa, Soundway, Soul Jazz, and Honest Jon’s undertook a massive archiving endeavour and, collectively, music’s global history is in the process of being meticulously restored and represented.

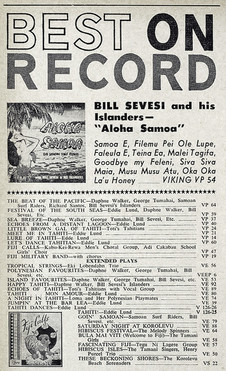

So where, then, are the lovingly compiled packages of music from the South Pacific, the songs and sounds from those old records and tapes produced by Viking, Salem, Armar, et al, between the 1950s and 1980s?

"Best On Record" Viking Records advertisement.

Yes, there are a couple of good CD collections from Ode – a Bill Sevesi set and a compilation of Mavis Rivers’ pre-Capitol material, recorded in New Zealand – but they’re 10 or more years old now and they barely scratch the surface of what was released by Polynesian artists during New Zealand’s vinyl era.

Try streaming/downloading vintage Pacific Island and Māori recordings and you’ll find a reasonable representation. Sonically though, it’s a mixed bag, ranging from what we might charitably call “indifferent” transfers to audio quality that’s good enough to demonstrate just how great the music could sound with sympathetic restoration and mastering.

In 2012 I digitally transferred over 200 songs from my collection of locally pressed LPs – Viking, Salem, all the major titles. There was talk of a possible vinyl release so I whittled down the tracks to a double CD to see what sort of shape a compilation might take. With careful transfers the music sounded amazing and the range and diversity of styles is impressive.

The vinyl project is a work in progress, but the two CDs of Pacific Island music became a mainstay around the house and in the car. I sent copies to friends and family, here and overseas and the reaction was always the same: “Whoa, nice – where do you get this stuff?”

--

Richard Santos – ‘Ou Auve Ae Maile’ (‘So Many Roads To Walk Home’)

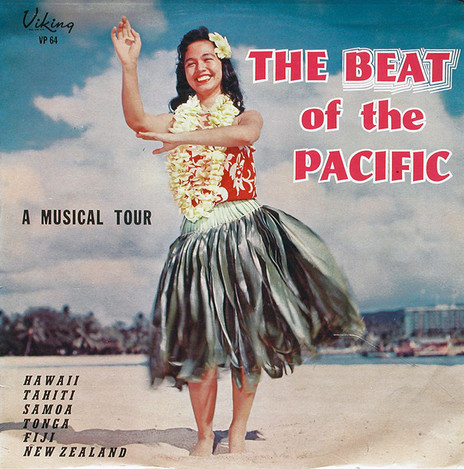

The Beat of the Pacific (Viking, 1962)

One of only two officially released recordings under his own name, Richard Santos’ ‘Ou Auve Ae Maile’ (‘So Many Roads To Walk Home’) kicks off this “Musical Tour” LP in fine Tongan-rockin’ style.

A guitarist in Bill Sevesi’s early 60s pan-Polynesian band, Richard “Ricky” Santos looks young, slim and eager in the few photos that survive from his New Zealand years. By the mid-60s he’d left the local scene for gigs in Australia, the Pacific and south-east Asia before settling in the US in 1973.

Sung in tight harmony with an uncredited female voice and interspersed by Sevesi’s simple but elegant steel-guitar breaks, Santos’ ‘Ou Auve Ae Maile’ deserves its place on the top of this list because of its undeniable quality, not its scarcity.

George Tumahai and his Tahitians – ‘Tahiti Nui’

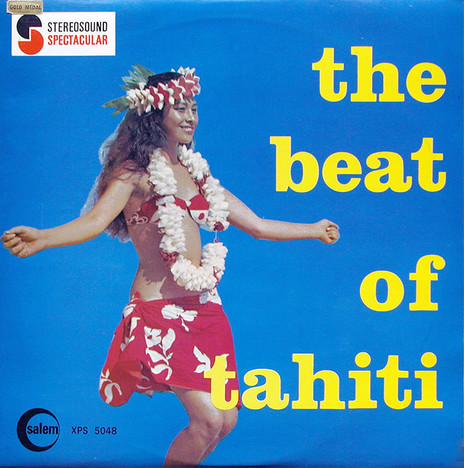

The Beat of Tahiti (Salem, 1969)

George Tumahai sings a version of ‘Tahiti Nui’ on Viking’s The Beat Of The Pacific release but it’s this later interpretation (recorded in 1967 but compiled on LP in 1969) where, with the wind in his sails, his magnificent voice can be heard to best effect.

‘Tahiti Nui’ is one of the great Polynesian belters in the classic maritime folk tradition. The only English lyric I could find – courtesy of a mid-70s translation by the South Pacific Creative Arts Society – tells of a young Rarotongan lad recruited (i.e. all but press-ganged) by a French mining company to dig phosphate on the island of Makatea.

While stopping off in Tahiti for a Customs check the Rarotongan lad leaves his ship and in short order hits town, hits the grog and is hit on by a local girl who takes him home. Waking with a very sore head – and the girl a lot less friendly than she was the night before – he stumbles out to find that his ship has already sailed. Far from home, jobless and spurned by the girl, the beautiful island of Tahiti seems now like a jail. He bemoans his fate: “Oh, I’ll have to return to my mother …”

But in Tumahai’s buoyant delivery the lad’s anguish at making his own way back to Rarotonga seems, possibly, only a temporary setback. Might there yet be further adventures?

The (uncredited) band are with George all the way; an insistent pātē – the Tahitian slit-drum – provides momentum as a gorgeous chiming electric guitar evokes new horizons beyond the reef, out in the wild blue yonder.

The Royal Tahitian Singers and Dancers – ‘Toere’

The Tahitians (Viking, 1962)

There are a fair few kitsch LP covers in the Viking back catalogue but occasionally the kitsch crossed over into seedy, even sleazy territory.

Karin Williams, film director and producer, has Cook Islands Māori whakapapa and made the beautiful film Mou Piri: A Rarotongan Love Song.

I wanted her perspective on these sexualised depictions of Polynesian women. “I think people in the mid-20th Century weren’t asking questions about representation and authenticity,” she said. “There was a blind acceptance of these portrayals – both the National Geographic factor and tropes going back to Cook and early colonisers.”

The Royal Tahitian Singers and Dancers were one of a number of itinerant troupes organised by Tahitian-based American expat Eddie Lund. It is Lund’s name that you’ll see most frequently on the label credits of Viking’s Polynesian records of the 1950s and 60s. Writer, performer and producer, Lund’s triple-threat talents placed him centre stage in the South Pacific’s music business.

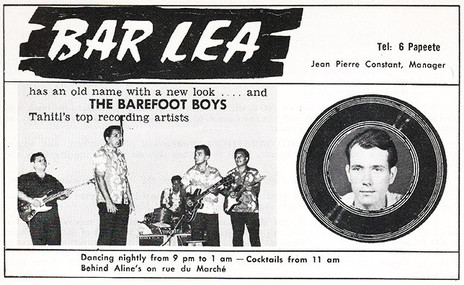

Bar Lea promotional flyer

Operating firstly out of Papeete’s infamous Quinn’s Bar, then later from his recording studio on the premises of the groovier Bar Lea, Lund licensed the music he recorded to Viking for distribution across Australasia and the Pacific.

He also sought tapes from Murdoch Riley for release on his US distributed “Tahiti” label and, via another deal with Vega Records in Paris, channeled Viking recordings into Northern Europe.

Central to Lund’s enterprises were two Tahitian sisters, Loma and Mila Spitz. Mila spent a couple of years in New Zealand in the early 50s while Loma went to Australia. Meeting again in Papeete in 1959 the sisters were signed by Lund to sing as a duo at Quinn’s where they became the darlings of a new tropical mileu: Tahiti – a la Belle Époque.

The tracks on The Tahitians LP were recorded in Melbourne in 1961 during a stop off on one of Lund’s South Seas tours. Mostly its good quality ballads and love songs with Loma on vocals but the frantically exciting instrumental ‘Toere’ is a jet-age Ori Tahiti – a fusion of traditional pātē percussion breaks and an electric guitar that leaps and darts to thrilling effect.

Gabylou and the Tahitian Barefoot Boys – ‘Korero-Timau’

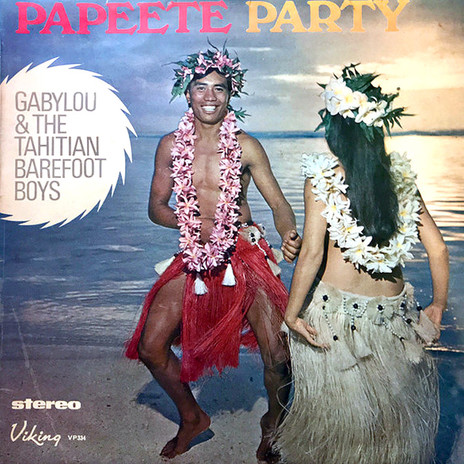

Papeete Party - Gabelou and the Barefoot Boys (Viking, 1971, recorded in 1966/67)

International eyes were on Tahiti in the early 1960s. Marlon Brando was in town for Mutiny On The Bounty, pioneering rock ’n’ roller Bill Justis had a hit across Australasia (No.1 in Australia) with the Tahitian-tinged ‘Tamoure’, and American tourists were flocking to the islands for a slice of the tropical action.

Bill Justis - 'Tamoure' - a No.1 hit in Australia

TEAL, the precursor of Air New Zealand, saw an opportunity to expand its services to Papeete hoping to carry some of the wealthy US tourists back through New Zealand. They sensed a travel bonanza but a number of Tahitian locals were less than impressed: “Americans Not Wanted!” said the Tribune Tahitiane as anti-US graffiti appeared on the streets.

Back in France the notion of a new Belle Époque in Oceania tickled a romantic fancy. Pictures of Brigitte Bardot on her Tahitian honeymoon sweetened the deal and helped attract a demi-monde of European partygoers into Papeete’s nightspots.

As the decade progressed Bar Lea became the happening place and the most happening band was Les Barefoot Boys. Their leader – local guitar hero Petiot Tauru – found a suave young singer called Jean Gabilou and asked him to join the group. Together they were a sensation and at that point, in 1967, arguably the greatest band in the South Pacific.

Gabilou’s voice was immaculate and the group could turn out pitch-perfect two and three part harmonies without breaking a sweat. They were flash too, looking great in their matching red and white hibiscus-pattern shirts. But their time together was all too brief.

‘Korero-Timau’ (a full lyric translation would be welcome if there’s any Reo Tahiti speakers out there?) appears on their Viking LP Papeete Party. The whole album is top quality but this particular track exemplifies the shimmering, modern electric sound and technique the group brought to Polynesian music.

And la Belle Époque? Well, it was a chimera, obviously. How could it not be after the French government’s first detonation of a nuclear bomb on the Pacific atoll of Mururoa, 2 July 1966.

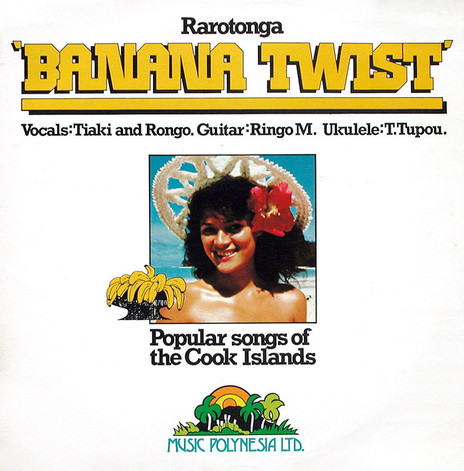

Tiaki, Rongo, Ringo M. and T. Tupou – ‘Taua Banana’

Banana Twist (Music Polynesia, 1979)

Where there’s tourism there’s tension. It’s the nature of the beast – the sting in a very long tail that stretches back to Empire days. Small island nations gaining independence from colonial rule had to address their population’s social needs. To do that capital was required for infrastructure and industry.

Choices were limited though and decisions were tough: Exploiting natural resources through mining and/or plantations or – as the jet-age developed – exploiting the natural resources through tourism?

Banana Twist label side 1, featuring 'Taua Banana'

Either option still required foreign investment and that usually led to a large part of the income from such ventures being extracted and funnelled back overseas, thus fuelling tension…

An article in Pacific Islands Monthly of May 1977 is headlined “Bigtime hotel business comes to Rarotonga.” It’s a piece of boosterism for a slick new hotel development whose principal developers were Air New Zealand, the Tourist Hotel Corporation of New Zealand and the Cook Islands Government. A pretty dull read really, except for a critically negative flourish about the island’s oldest hotel, Otera Rarotonga:

“The only real interest the old hotel must now have for those seeking the thrills of island life is the bar, known as the Banana Court. Here are gloom, rudimentary service, loud music, disorder and old island identities.”

If, like me, you read that and thought, “hold on a sec, that actually sounds sort of great!” then have no fear because, though the Banana Court, is long gone its audio spirit lives on.

The Banana Twist LP plays like a call to action, a rousing blast of Polynesian juke-joint militancy. Its subject is the old Otera Rarotonga’s Banana Court bar and its precarious position in the face of tourist-related gentrification. Apparently (I’m going on the fairly brief sleeve notes here) “Bush Beer Drinkers” were bringing their “Mountain Manners” to the bar hence the “loud music and disorder” reported by PIM. So it would appear unseemly behaviour was the promoters’ issue, especially when there were “sophisticated” tourists in town.

Tensions then. But oh, what music! ‘Taua Banana’ is a glorious mash-up of traditional Polynesian string band and fantastic, late-70s Human League electronic rhythm box. It’s the friction between these two styles that is so wonderfully exciting – the frantically scrubbed guitar and ukulele, busked like there’s no tomorrow, urgent vocals and, at the root, the primitive metronomic beat; a new technology with the potential to unsettle the old order.

There’s no doubt in my mind that I’d be more than ready for a hooley if this was the sort of music that soundtracked the Otera Rarotonga. And its likely too that, with ‘Taua Banana’ blasting out through the disorder and tropical air, the bar at the ramshackle old hotel must surely have qualified as one of the greatest nightspots in the world.

--

Read more: Pacific Romance: Rhythm of the Islands, part two

A National Library playlist of songs from seven Pacific Islands