“It’s where we learned to rock ’n’ roll,” says Christine Panapa, the matriarch of Auckland’s Te Mahurehure Marae (at Point Chevalier), remembering the Māori Community Centre in central Auckland.

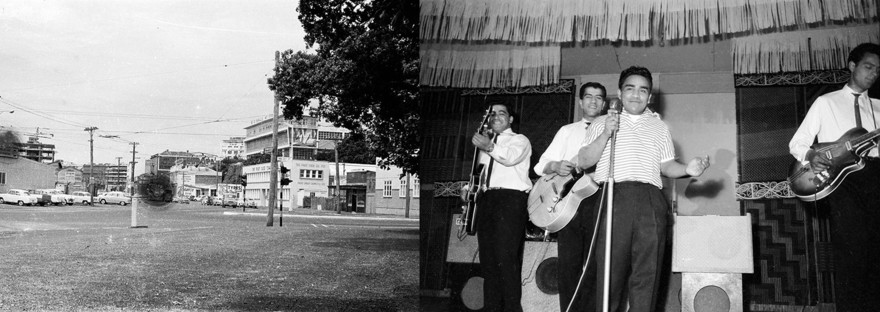

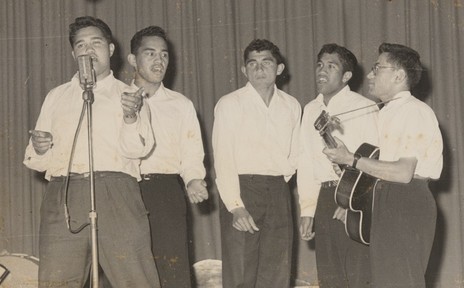

The Māori Community Centre, on the corner of Fanshawe and Halsey streets, is on the far right in this 1965 photo taken on the northeast corner of Victoria Park, Auckland. On stage are the Quin Tikis, 1961. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 786-A17-01 and 1269-E0139-12

Of all Aotearoa’s celebrated venues, the centre stands out for the range of performers who made their start on its stage. Names such as the Māori Hi-Five, The Keil Isles, The Quin Tikis, Sonny Day and the Sundowners, Toni Williams, Robbie Ratana, the Māori Volcanics, Bunny Walters, and the Yandall Sisters stand out in the listings published each weekend.

It wasn’t just a place for music. It was, at its heart, literally a centre for community.

Dilworth Karaka and Charlie Tumahai of Herbs revisit the Māori Community Centre on Halsey Street, 1990. - When the Haka Became Boogie/NZ On Screen

From the outside it still looked like a warehouse, covered with khaki-coloured corrugated iron, with windows high up.

It was one of a cluster of warehouses and facilities thrown up around Victoria Park to service some of the 100,000 United States Army troops heading for the Pacific during World War Two.

Prime Minister Peter Fraser being welcomed to the opening ceremony of the Māori Community Centre in Auckland by Tapihana Paraire Paikea, the MP for Northern Māori, 9 July 1949. - Tourist & Publicity collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. Ref: 1/4-016776-F

In 1948 then-prime minister and Māori affairs minister Peter Fraser ordered it to be used for the many Māori migrating the city. During what’s been described as one of the fastest rates of urbanisation in the world, the Auckland’s Māori population grew from 4900 in 1945 to 35,000 by 1966.

The centre had an unofficial opening in November 1948 – in time to hold a reception for Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Buck), visiting briefly from his role running the Bishop Museum in Hawaii – and an official opening on 9 July 1949. Mei Watene, daughter of prominent community organiser (and later Eastern Māori MP) Steve Watene, was first to step over the lintel.

The managing trust initially included Rotary and the Returned Services Association along with the Māori Women’s Welfare League, which was born in the centre, and the Waitemata Tribal Executive dominated by Ngāti Whātua, whose association with the site went back centuries. Where Victoria Park Market now stands – a stone’s throw across the park – was a major Ngāti Whātua kaīnga, Te Tō.

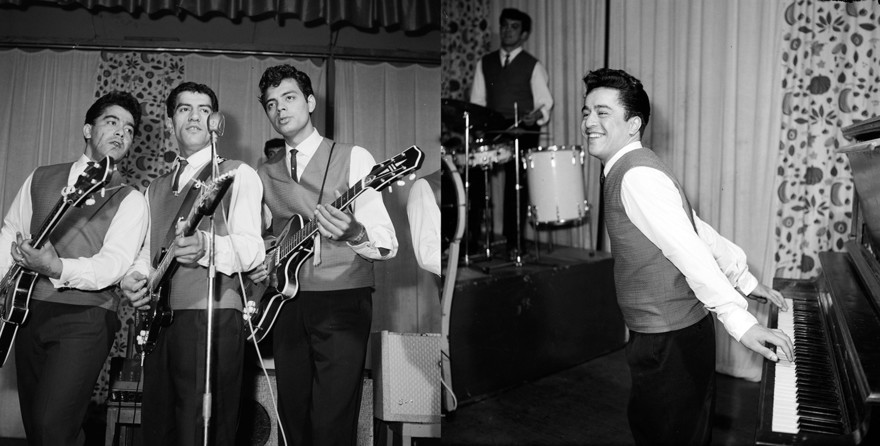

The Quin Tikis at the Māori Community Centre, 22 September 1961. - Rykenberg, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-L0591-07 and 1269-L0592-08

Many of the rural Māori who came to Tāmaki Makaurau found cheap housing around Ponsonby, Freemans Bay, Newton and the slopes leading down to the city centre – all in walking distance of the centre.

They were young, they had money in their pockets and they were looking for fun and company after they finished their jobs in the offices, factories, warehouses and wharves of the city.

Harry Akarana literally grew up in the centre, where his mother Tumanako Reweti – known by all as Auntie or Nanny Hope – oversaw the kitchen and confectionary shop.

He remembers the constant activity and the hold the women such as his mother and future land march leader Whina Cooper had on the place.

“They all looked after me,” he says. “It was wonderful for Māori because it always smelled of boiled meat and cabbage,” says Akarana’s cousin Temepara Morehu, whose group The Sunbeams started performing at the centre in 1957 as a Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers-style singing group and ended up as the house band in the early 60s.

The Sunbeams reminisce, 2025 (L-R): Maurice Watene, Temepara Morehu, and Harry Akarana - Adam Gifford

Another Sunbeam, Maurice Watene, says they grew up between the centre and Kitemoana St in Ōrākei, then known as “Boot Hill”. He was six or seven when the band started. Temple was a year older.

“In those days we were in the Māori Community Centre all the time. On Sunday, in the daytime we always thought we went there to go to the swings over on the corner, but they had church service,” Watene says.

“In the community centre there would be Māori Women’s Welfare League meetings for half the day, then Dobbie (Dobson) Paikea, the MP for Northern Māori would take over for his Labour meeting, then the Ratana church would meet until the dance or the talent quest started,” he says.

There were games of rugby every weekend across the road in Victoria Park featuring factory or company teams, and the tennis court leased to the centre was also in constant use, with the star being Ruia Morrison, who reached the fourth round at Wimbledon in both 1957 and 1959.

“We helped fundraise for her to go to Wimbledon. She had pride of place because she used to practice at the tennis court,” Watene says.

According to the Māori Affairs Department’s magazine Te Ao Hou, the dances started out as formal collar-and-tie affairs, with the music supplied by some of the many Māori musicians in the city’s thriving jazz and dance band scene. But as rock ’n’ roll took off, attendance fell off until management wised up and followed the trend.

It would regularly draw in 500 people for the Friday and Saturday night dances, and that could double for the big Sunday night talent quests.

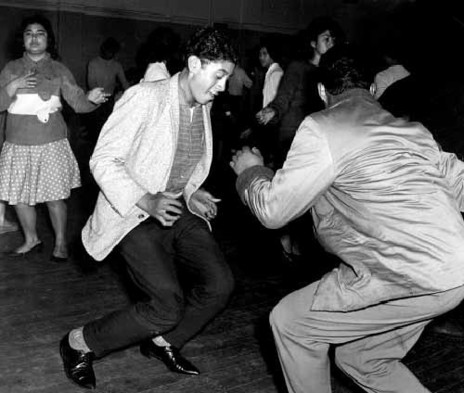

Dancers doing The Twist at the Māori Community Centre, 1962 - Ans Westra, Archives NZ, AAMK W3495/28H; Digital NZ, CC 3.0

A series of photos by Ans Westra held in the Alexander Turnbull Library show the centre in 1962 with people of all ages twisting and jiving the night away.

Future advertising mogul and Waitakere mayor Sir Bob Harvey was a regular visitor in the late 1950s. “I’m 17 and 18 in 1957 and I’m working at the St James [cinema] and on Saturday nights about 10.30 I would often finish up at the Māori Community Centre. There was jiving – not rock’n’roll dancing – that came later, and some people would waltz. In jiving, people would not touch.

“It was fantastic music. I remember the saxophones – they had a lot of saxophones.”

A room near the stage was the domain of the “aunties”.

“They ran the kitchen and they ran the place and supervised the young girls. They sorted out who could dance, and if guys got horny and started to rub up against a young woman, as young guys do, they’d say ‘cut it out’.”

They also enforced the ban on alcohol, and when the dances ended at midnight, or later on a long weekend, the hall would be cleared quickly, leaving patrons to taxi or take the last tram, or to walk home. “The streetlights went out about 11pm, so the whole of Auckland went dark,” Harvey says.

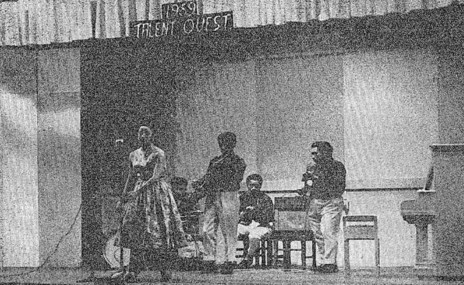

Freda Morrison, backed by the Hawaiian Swingsters, at a talent quest held at the Māori Community Centre on Fanshawe Street, Auckland. - Te Ao Hou, June 1959, Papers Past

Former MP Dover Samuels, who was then working at the Southdown freezing works, says while all-seeing manager Waka Clark and the Māori wardens on the door made sure no alcohol got inside, there was a sly grogger parked around the corner willing to lubricate proceedings, and there were plenty of places to hide a flagon or hipflask in the oak trees along Halsey St.

“This was the era of six o’clock closing. After work or rugby, we’d go to the Oxford or the Empire, and when they booted us out we’d go down to the centre,” he says.

“There were no scraps, no violence. The wardens kept discipline and there was also respect. A number of Ngāti Whātua who lived on Boot Hill were policemen anyway, and they’d be in and out – we knew them all because they were part of the rugby team.

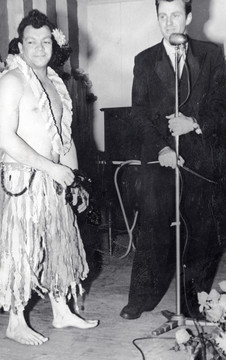

Trevor Rupe - later known as Carmen - with Lou Clauson at the Māori Community Centre, late 1950s. - Lou Clauson collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. Ref: PA1-f-192-17-15

“It was an entertainment centre that accommodated the migration of Ngāpuhi from our nīkau houses to the bright lights, and not just Ngāpuhi – Māori from all over.” Not to mention the strong representation of Cook Island Māori and other Pacific Island migrants who were made welcome.

He says the centre was the place Māori musicians would gather after they finished their paid gigs at dance halls such as the Masonic Hall and the Orange Ballroom.

Scanning the listings for the talent quests, some now-familiar names shine out among the many unknowns.

The finals for the 1957 Christmas competition included Ricky May and Rusty Greaves, with Kahu Pineaha as the guest artist.

The following Christmas, The Starlighters – a group from the Ardmore Teacher Training College in Papakura led by Buddy Wilson – made the final. An acetate recorded by the band in Lou Clauson’s Papakura studio features a repertoire ranging from ‘Hoki Mai’ to ‘At the Hop’ and ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’.

Wilson, who maintained a music career alongside his time in the classroom, including a long partnership with steel guitarist Ben Tawhiti, still remembers the band travelling up from Papakura crammed in their manager’s car.

The Starlighters in full flight, Ardmore, Auckland, 1957; Buddy Wilson with guitar. - Lou Clauson collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. Ref: PA1-f-192-31-17

By 1960 there were 15 weeks of eliminations for the end-of-year quest. The final, compered by Lou Clauson, included Simon Meihana – who shortly after teamed up with Clauson as the successful pop comedy act Lou and Simon.

Eddie Howell, who contested the talent shows when he returned to the city and went on to a brief music career – including recording several singles for Stebbing and one tour with the Howard Morrison Quartet – says the open mic was part of the atmosphere of the place.

“We were Māori – ‘yeah, I can sing’ – and even the buggers who can’t sing, some should have been shot when they were born, but this was our humour, we’d have good laugh, crack up. You’d have good ones, bad ones, and nobody cared. It was a wonderful place to go to at that time. And there was no beer.”

There was a huge pool of musicians to call on to back the singers. “There were a lot of good musicians among the Māori but they didn’t read music. The ones I played with on Zodiac records, Eldred Stebbing and them, they were all readers of music, but it doesn’t mean to say they were as good.

“The old Māori, it was in the ear, one two three four kia ora, and they could make a song swing whereas these guys could read music and it was one-two-three-four. When you’re singing you want to ad lib and play round a little round.”

Glyn Tucker Jr entered the talent quest in early 1959. “I remember that night. It was the only time I went tothe Māori Community Centre, not long after family moved up from Upper Hutt. My dad would have driven me in from Howick.

“I was a real novice doing a rock’n’roll song, a Johnny Devlin rip-off or similar. It would have been pretty awful. I was about 16. I had my first proper electric guitar, a Hofner, I was proud of that. It was the same as the ones The Beatles used in Hamburg before they became famous. I’ve no idea what I sang, but I just did it on my own. It’s pretty lonely to try to do rock’n’roll like that but I didn’t know any better,” Tucker says.

The same weekend Tucker made his talent-quest debut, the centre held a party for the visiting American group, The Platters. “Free dancing! Free supper! Ladies free. Gents 2/6.” Entertainment was by Swalgers’s Samoan Swingers and the university and training college Māori clubs.

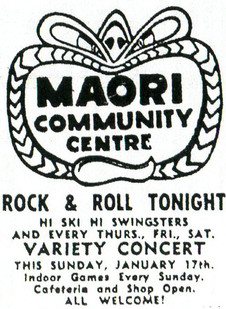

Māori Community Centre, 1960: rock'n'roll three nights a week (Auckland Star advertisement)

It was not unusual for foreign acts to end up at the centre, or be lured up for house parties at the Ngāti Whātua enclave on Bastion Point. “Uncle Jim was a mate of all the promoters, he would go along and bring them up,” says Temple Morehu.“The Ink Spots came. Nat King Cole came out here to someone’s house. He may have sung a song. His voice, when he talked, you could hear the tobacco gravel in his throat.

“Winifred Atwell came, someone approached her and she came here.”

Christine Panapa remembers the Harlem Globetrotters basketballer as guests of the Māori Community Centre during their frequent New Zealand tours in the 1960s.

“I remember on three occasions them coming to the centre and Nanny Hope welcoming them, mum and the other aunties making them a big kai and they all slept there,” she says.

Even after the talent quest was finished there might be a midnight dance, headlined by the like of The Keil Isles.

“When they had that, us young ones all had to sleep in a room to the side,” she says.

As the 1960s wore on, Māori were spreading across the city and raising families in suburbs like Ōtara, Glen Innes, Manurewa and Te Atatū, and also creating urban marae.

Whina Cooper led the Auckland Māori Catholic Society to buy a large bakery on Manukau Rd in Epsom to turn into Te Unga Waka Marae for the Catholics from north Hokianga.

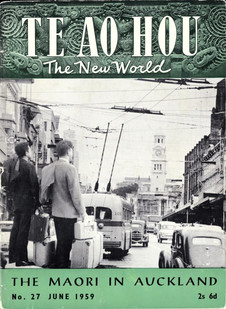

Te Ao Hou was a bilingual quarterly published by the Māori Affairs Department from 1959 to 1975. As well as covering current affairs, it occasionally reported on Māori musicians. The June 1959 issue was a special edition on “The Māori in Auckland”. - Papers Past

Christine Panapa’s elders from the southern side of the harbour bought a dirt-floored rugby league club training shed near Western Springs and turned it into Te Mahurehure Marae, where many of the performers from the centre played over the years for fundraisers and socials.

Panapa and husband John also organised a Māori showband reunion concert in 1996 that drew 1000 people to the Downtown Convention Centre.

The Ōrākei Marae Committee took over the lease for the Māori Community Centre and let it out for social functions, as well as using it as a workshop to make the carvings and tukutuku panels for the marae being built on Takaparawha-Bastion Point.

In the mid-70s the lease was picked up for J Team, a joint initiative by Māori Affairs, Social Welfare, police and community members which attempted to address crime and juvenile delinquency.

In 1981 Ana Tia from Ngāti Kuri, one of the stalwart “aunties”, with support from Ranginui Walker of the Auckland District Māori Council, took over the centre as a base for the work she was doing with Māori youth in prisons and on remand, as well as continuing to host Ratana services until her death in 1990.

It continued to be used for work schemes, but its days were numbered. In 2004 Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, which had a claim over the site, resolved the ownership by buying it from the crown and co-developing a five-storey office, block, which is now worth $50 million.

--