“Boy is what they call me, but my real name is Charlie.” That was the catch-cry the cousins living in Kitemoana Street, Ōrākei, responded to as Charlie – or Boy as he was known – and the bros headed for another day of mischief down at Okahu Bay, or at the vacated World War II gun emplacement camps at Bastion Point.

The days usually ended with one of the bros nursing an injury from a bow and arrow, or a shanghai fight down at the camps, and Uncle Digger Maihi breaking the bows in half and giving us a whack around the backside. It always seemed to be Charlie who got a whack, he wasn’t fast enough to run past our uncle’s house – that’s why he was also nicknamed Weeps.

‘Hey Boy!’ was based on a perspective of a Māori community from a young boy’s eyes.

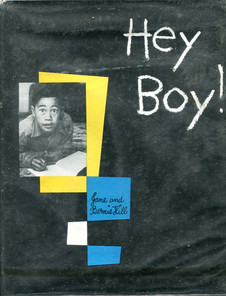

Jane and Bernie Hill – friends of the family who worked as a freelance writer and photographer for the NZ Herald – published a book which those of us now in our 40s can probably remember. Hey Boy! was based on a perspective of a Māori community from a young boy’s eyes. Charlie, my family and the whānau at Ōrākei were the main characters in the book. This was Charlie’s first claim to fame. The book was published about 18 years after all the whānau moved from the papakāinga down at Okahu Bay up to Boot Hill as it was known in those days.

Boy’s musical talents were inspired by our grandfather, Daddy Francis. He was Tahitian, so Charlie reckoned we are half hula and half haka. Daddy Francis was a member of a French minstrel show that was touring Aotearoa. He played the banjo real awesome. He met our Nana Maude at a show in Auckland and to stay with her, he jumped his ship, which was on his way back to Tahiti, as it passed the Ōrākei wharf. He swam to all the cousins and my Nana waiting at the end of the wharf. They hid him from the authorities, down at the papakāinga, until they finally got married.

Hey Boy! featuring Charlie Tumahai (Whitcombe & Tombs, 1962)

Charlie’s days of mucking around with Daddy Francis’s banjo and the piano they had in their house eventually saw him advance to the guitar and a stint with his cousin’s band, the Sunbeams. Young teenage kids playing in bands were all the rage in those days and the success of the group and the talent and experience they gained were never lost. They were to be experienced in later years through the exploits of the top 80s and 90s band, Herbs.

The Sunbeams at the Maori Community Centre, 1960; Lou Clauson at right. "When Dad comes to get us we are glad to get home to bed, but most of the grownups stay on and dance until very late." (Hey Boy!). - Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, PA1-f-192-17-03

Experiences of the 60s were very productive for Charlie’s musical career. Tommy Adderley and Ray Columbus and the Invaders were making waves around town at the Shiralee and the Top 20 club. The old Trades Hall up at Hobson Street was the stomping ground of the whānau and all the whanaunga from around Aotearoa who were in Auckland.

They would converge on the Trades and rock’n’roll to a brand of music and rhythm that attracted most Māori to the hall. Charlie played the bass guitar – totally engrossed in what he was playing, standing on the stage in his grey-flannel suit with that piece of velvet up around the back of the collar, white shirt, thin black tie, Beatles-style haircut – very 60s.

Charlie was oblivious to the attempts of his tāne cousins on the dancefloor, daring each other to go over and ask the Pākehā sheilas sitting on a form across the room for a dance, because all the wāhine cousins insisted on dancing with each other. The tānes would eventually get hōhā, leave and walk down the road to the Picasso where most of the Pacific Islanders used to hang out.

I think a lot of the stories they told us about the Picasso and their attempts to imitate a scene out of West Side Story, were a lot of teka. I think they used to go down to the Picasso, just stand there, Coca-Cola in one hand, one of those old rubbish tin lids in the other, flex their muscles, yell some abuse, get hungry and go down to Mr Chips for a big feed, then go back to the Trades Hall. There would be Charlie and the band, bouncing out the music, the wāhine still dancing with each other, and the Pākehā sheilas dancing with the clever tānes who decided to stay at the Trades.

A stint to Australia playing for bands, among them Healing Force, whose Top 30 hit ‘Golden Miles’ saw Charlie travel to England, eventually joining the acclaimed group Be Bop Deluxe. There are two things I can distinctly remember from when Charlie was in Europe. The first is the live broadcast on Aotearoa television of a concert Be Bop Deluxe were performing in London. My dad sat there, watching the TV with excited anticipation, Charlie and the band booming this new-wave sound out of the box. When it was all over, I remember my dad saying: “What the hell was that?” He was totally divorced from the message in the music and lyrics, and being a hairdresser by trade, he couldn’t wait to get at Charlie’s afro haircut when he returned to Aotearoa. It is probably understandable as he was in his 40s.

The second memory is from a visit to London in 1979. We were walking down a London street to a pub, and on the way we passed groups of West Indian tamariki and rangatahi who were kicking soccer balls, playing guitars and just hanging out. They would call out: “Hey Charlie Maaan,” with that distinctive Bob Marley drawl, “teach me a few chords on the guitar.” Or, “Hey Charlie Maaan, have a look a my song.” For an instant I flashed back to Hey Boy! and Kitemoana Street, but here we were in the middle of London, all these kids attracted to him like a magnet. Charlie would of course stop, teach them a few chords, jam with them, show them what George Best should be doing with a soccer ball, then remember half an hour later that we were going down to the pub. That magnetic influence he had over rangatahi was to play a significant part in his life on his return to Aotearoa.

Charlie Tumahai, Greenpeace Concert, Mt. Smart, 5 April 1986

Back in Aotearoa, Charlie’s history is well documented in music and lyrics from his stint with Herbs. He and his cousins, Maurice Watene and Dilworth Karaka, enjoyed a successful relationship in the development of the band’s style from when Charlie joined them. The message in their music was to gain the band many successes in Aotearoa and the Pacific, in particular the song ‘French Letter’ which was inspired by French nuclear testing in the Pacific.

It is sad to say that Charlie found his niche in life just before his death. His ability to respond to rangatahi of all nationalities and his influence over them as a popular musician prompted him to take a break from Herbs to return to his roots and develop his interest and education in his culture and language.

Prompted by his Uncle Danny and Aunty Jose Tumahai to action, rather than korero, Charlie became involved with youth justice. His work in the courts and the justice system, helping rangatahi and social workers to steer these young people in the right direction, gave Charlie a tremendous degree of satisfaction and self-worth.

A typical day at the courts in Albert Street is shown in Charlie’s story about a young offender peering at him through a pair of dark shades like something out of Once Were Warriors and saying: “Hey bro, you have made my day. You’re that fella from Herbs.” After repeating this sentence a few times over, Charlie said: “Hey bro, now you make my day. Now when you go before the judge, I want you to behave like this.”

This was the influence he had, and was an influence that motivated Charlie in his work to develop a dream: to use his years of musical skill and experience to help young people by starting a musical school for young rangatahi at risk, to give them something to do and replace their lives with activities that might teach them a skill. Perhaps among them, there may have been another budding musician.

Working with his Aunty Esta Davis and the kapa haka group at the marae, he was able to introduce another dimension to the waiata which was also satisfying. Unfortunately, his dream was not to be. Whether it was time for him to join our tīpuna, or just plain bad luck, Boy’s life was taken at a time when he had found a new goal and meaning in his life.

The memories of what Charlie had given to his family, friends, fellow musicians – and, for a short time, to those young people at the courts – will not be forgotten. This was exemplified in that brief impromptu concert at the marae performed by his friends and fellow musos. On behalf of the family, I thank all those who expressed their kind thoughts and best wishes, and to Annie Crummer, Ray Columbus, Matty J and all the other musos.

You made his day.

--

This first appeared in Te Māori News, January 1996, and is republished with permission.