Gareth Shute recounts writing Songs From The Shaky Isles: A Short History of Popular Music in New Zealand.

--

Aaradhna, as seen in Songs From the Shaky Isles - Photo by Gareth Shute

I swore I’d never write another book. In my early years, I wrote four books in five years and still managed to squeeze in three overseas tours with bands over the same period. I remember getting back from a show in London with The Brunettes and arriving at the flat of the band’s manager Melinda Olykan and, while everyone else set up places to sleep in the lounge, I pulled the corded phone into the hallway and did an interview with Grant Smithies back in Nelson to promote my book NZ Rock, 1987-2007. It was a difficult juggling act.

Yet despite myself, the past few years have seen me imagining the outlines of a book. It’s been over 20 years since David Eggleton made the last attempt at an overall history of local popular music. More recent works have been in-depth investigations into particular scenes. Case in point: Needles and Plastic: Flying Nun Records, 1981-1988 (Matthew Goody, Auckland University Press, 2022), which examined the first eight years of Flying Nun at length. Great for music nerds like myself, but perhaps too obscure for the general public. Surely, someone needed to go in the opposite direction and show the overall path that popular music has taken in this country?

Songs From The Shaky Isles (Bateman, 2025) is my attempt to write a high level, fast-paced account of popular music in this country.

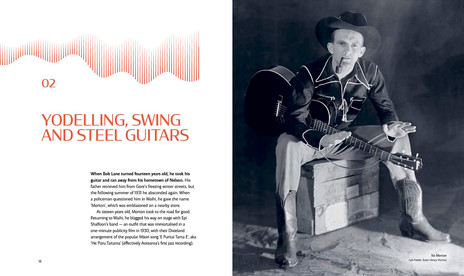

Yodelling, Swing and Steel Guitars - Tex Morton in Songs From the Shaky Isles, Chapter 2

But what do I even mean by “popular music”? For me, the word “popular” suggests music that can be heard by anyone. This wasn’t really the case for songs written prior to the arrival of radio and recorded music. Both Māori and Pākehā had strong oral cultures, which saw songs and waiata passed on from person to person but there was a limit to how far these could reach (though one might point to the incredibly wide reach of the ‘Ka Mate’ haka, written around 1820, as an exception).

Sheet music was also popular, especially due to the country’s high rates of piano ownership, so I did want to write about this back story, though the majority of the book is focused on the era of recorded music, which allowed songs to reach right across the country and even overseas. The aim was to present the story in such a way that you could see the wood for the trees, so that anyone interested in our country’s cultural history was able to follow the changes over time, without being dragged down into the weeds.

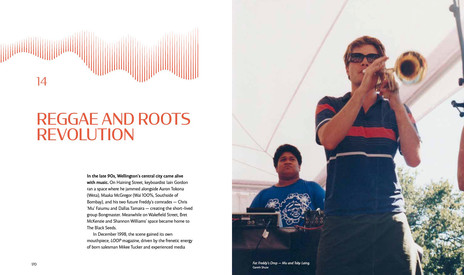

Reggae and Roots Revolution - Fat Freddy's Drop in Songs From the Shaky Isles, Chapter 14

The other benefit is that taking a high-level view allows you to see how different external factors influenced the path of our music scene. For example, why were so many of the music venues in the 1970s connected to hotels? The only way to understand this is to know that in the late 1800s, there was a law passed that required applicants for a liquor licence to also show that they could provide at least six rooms of accommodation (in order to help increase the lodgings available for the growing population). These public bars (aka pubs) connected to hotels were the obvious place for bands to perform once six o’clock closing ended in 1967.

Rodney Fisher from Goodshirt. - Photo by Ian Jorgensen

It was remarkable to discover how much control breweries had over the live scene in the 1970s (particularly Lion Breweries). They even created their own bands with product-placement names such as “Distillery” and “Beam” (when they wanted to promote Jim Beam whiskey).

Another trend more visible from sky-high was the impact of new technologies. There would have been no chance of music festivals without PAs big enough to project the sound to such a large audience. In contrast, acts in the 1960s usually only used PAs for their vocals and relied on their amps to be big enough to be heard directly – this was even the case when The Beatles played the Auckland Town Hall. This improvement in PAs also helped give rise to DJ culture in the 1980s, since it allowed someone playing a record to sound as good as a live band (probably better in some cases).

Technology would cause even bigger changes in the new millennium, when digital approaches completely altered both how music was made and how it was listened to. In this case, it is impossible to fully appreciate the current situation we are in without looking back at how we got here. The only reason streaming was able to take such an overwhelming hold on the industry was due to the damage that illegal downloading had done to it in the early 2000s.

Head Music - Human Instinct in Songs From the Shaky Isles, Chapter 4

Yet there was still a question as to how I could bring these types of themes to the surface and include all the major acts without getting too bogged down by the individual stories of all the amazing acts that this country has produced. I needed a way to narrow my focus.

I decided one key in deciding how much space to give to an act would be whether they wrote original songs and/or whether they found success overseas. There were plenty of acts who found fame in the 1960s simply by covering songs from overseas before the originals could arrive here. While the best of them were important to mention, I did want to highlight those trailblazers who managed to write their own songs, even if some of them gained interest in later decades. After all, aren’t these original songs the ones that will live on?

Through the process of researching the book, I gained a new perspective on some of the changes that I hadn’t really appreciated before. For example, I always wondered what happened to all the musicians from Māori showbands once this form of entertainment started to fade out in the late 70s and early 80s. Taking a step back, it became clear that reggae became the go-to outlet for the musicians that otherwise would’ve played in these bands. Some even made the switch directly – for example, Willie Hona went from being frontman for cabaret act Hona to joining Herbs, while Carl Perkins was the drummer for the Hi-Marks before he joined Herbs, then formed Mana and House of Shem.

No wonder some of these reggae musicians took the same approach of working up a tight band by doing cover versions, until they gained enough of an audience to release originals. Even more recent groups such as Katchafire and L.A.B. took this route to success.

Troy Kingi. - Photo by Mieko Edwards

Once the text was in place there was still the job of collecting photos to go with it. I originally intended for the book to be black-and-white, since this was almost all that I took back in the days of film. Quite far along in the process, the decision was made to do the book in full colour instead, which left me scrambling. I was greatly appreciative to the photographers who allowed me to use their images, including my wife Mieko Edwards, who took the photograph of Troy Kingi that features on the back cover.

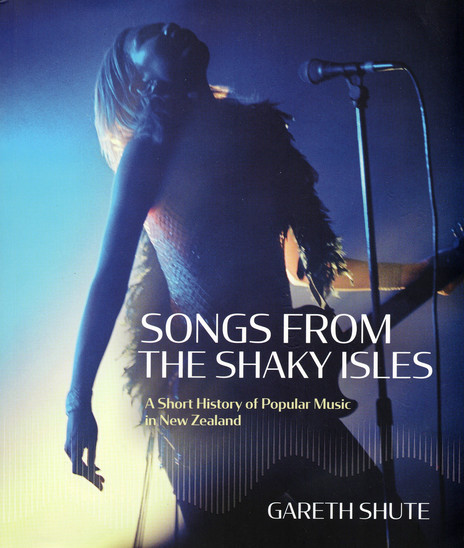

The visual look of the book was given coherence by the designer, Cheryl Smith. I’d always liked the old-fashioned slang term for New Zealand, “Shaky Isles,” with its playful reference to the fact that the country sits along the meeting point of two tectonic plates and therefore the ground might literally shake beneath our feet. The phrase was used in the classic 1960 rock’n’roll number ‘Shaking In The Shaky Isles’ by The Māori Troubadours and the 1991 Dave Dobbyn song ‘Shaky Isles’, plus we also used it for a Lil’ Chief CD sampler back in 2012 (These Shaky Isles). Cheryl referenced the name by placing subtle waves of lines beneath the title on the cover and alongside each chapter title, which also gave the sense of soundwaves moving through the book.

Gareth Shute - Songs From the Shaky Isles featuring Boh Runga from Stellar* on the cover. - Cover photo by Gareth Shute, design by Cheryl Smith.

The cover image was the hardest to choose. I wanted an evocative image, but also one that didn’t pigeonhole too strongly what the book was going to be about. I found a wonderful shot by Ian Jorgensen of Boh Runga, which seemed perfect. After all, Stellar* was amongst a small group of early-90s New Zealand bands that reset expectations of how successful a local act could be (Stellar* sold over 75,000 copies of Mix, the group’s debut album). Another goal of the book was to remind younger readers of just how bad it was prior to this – in the 80s and 90s, the main route to success was radio, but the programmers playlisted less than two percent local music.

Gareth Shute. - Photo by Mieko Edwards

So now the book is done and out in the world. I’ve already spotted a couple of things I wish I could change, but I’ll have to live with them. I certainly hope the book is an enjoyable read and that people are inspired to come back to AudioCulture to dig deeper into the fascinating history of the music made in our little corner of the world.