One News, 15 March 2023: “Te reo Māori words and Kiwi slang like chur will now be added to the Oxford English Dictionary as a part of a ‘Kiwi update’ totalling 47 words.”

It’s only taken 60 years, but a word popularised by Māori musicians is now officially part of the coloniser’s language. The Empire strikes back.

In the past couple of decades, “chur” has become common usage, taking over from the place “choice” had in the language in the early 80s. While the words can sometimes have a similar meaning – “thanks” or “that’s good” – they don’t always mean the same thing.

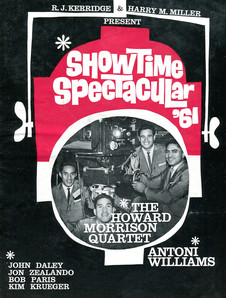

The Howard Morrison Quartet.

As etymologist Jimi Jackson explains on YouTube (warning: explicit language), the word can mean a lot of things: Hi, hello, congratulations, thank you or goodbye (“Chur bro”), and an all-purpose response (“True that” or “oh yeah?”).

“How smooth is that?” says Jackson. “It’s probably the best word ever, the best invented. And it’s from New Zealand.”

“Bro” is a recent addition. When first developed in the early 60s, the actual phrase was “Chur, doy.” Say what?

The Showtime Spectacular ’61 tour programme. The Howard Morrison Quartet topped a bill that also featured Toni Williams, Bob Paris, Kim Krueger, and magician Jon Zealando.

The phrase emerged from the Showtime Spectacular tour of 1961, a national tour headlined by the Howard Morrison Quartet at their peak, plus Toni Williams, Kim Krueger, and backing musicians such as Bob Paris and Bruce King.

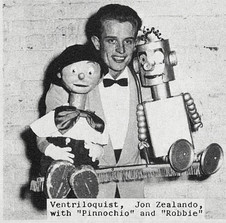

It was invented by a magician/ventriloquist on the bill, Jon Zealando. The Quartet was fascinated by his ability to speak without moving his lips when working with his metal robot puppet.

I had long heard chur used by older musicians: not just Māori but veterans who had reached the stage where they mixed beyond their genre, with variety performers, show bands, old hoofers. It was only when talking with Gerry Merito of the Howard Morrison Quartet in 2008 that I became aware of its background. I was asking about the self-deprecating humour of the era – the “eh boy” school of cheap laughs – and Merito said the Quartet dropped into that trap when they first went to Australia, where it only meant something to the New Zealanders in the audience.

Ventriloquist Jon Zealando with 'Pinocchio' and 'Robbie', August 1961. - Gisborne Photo News

“We didn’t need to. We didn’t even need to do it here for goodness sake. However we just slipped into it because it was habit. And then that silly language came along – Chur, doy – and we had a heck of a job getting rid of it in Australia.

“We started that language, and I still hear musos using it today. It came from Jon Zealando. We used to copy him from the side stage. We started the lingo off without moving your lips you see. So ‘gidday boy’ doesn’t work – that’s how the doy came into it.”

“Doy” is of course “boy” and when combined, “chur doy” became an all-purpose phrase when responding to a mate. A 2022 biography of Jon Zealando, written by magician Bernard Reid, goes into more detail:

“The two letters of the alphabet that give ventrioloquists major problem are the letters ‘B’ and ‘M’ which are the only letters that cannot be pronounced clearly without the operator’s lips moving. In writing scripts ventriloquists avoid these letters as much as possible by inserting alternate words but sometimes this is unavoidable.

“An occasional substitution for the letter ‘B’ is the letter ‘D’. Jon used this subterfuge in his act a couple of times. Hearing the act every night the other performers in the show ultimately became aware of this. Howard Morrison thought it was hysterical and adopted the practice by greeting everyone as ‘Doy’ instead of ‘Boy’. ‘Alright, Doy,’ became the catchphrase of the show backstage with everyone using this greeting. This carried on for years among the personnel of the show whenever they met. It is still heard today among older performers.”

Zealando describes how this caused problems for pianist Carl Doy when he emigrated to New Zealand in 1973. Quickly booked to play in many orchestras for musicals, Doy thought people were referring to him when they said “doy”. He recalled, “The word was used so frequently I had to immunise myself and react only to ‘Carl’.”

While Sir Howard was occasionally claimed he invented the phrase, he usually gave Zealando the credit – and used it so extensively he can be seen as its means of distribution. In a 2008 interview with Julie Jacobson of Stuff, he mentioned it was being used by much younger Māori. She wrote:

They also introduced a new word to the New Zealand lexicon, one that is still used today, most often by a generation twice removed from theirs, and created their own “Quartet language”.

“Chur,” Sir Howard hooted. “Chur doy, chur,” which, translated, means something along the lines of: “Well done, mate.”

“There was a ventriloquist we worked with who couldn’t say his Gs; they became Ds. Some other letter became T. Gerry picked up on it and we all just started talking like that.”

Of course it wasn’t because Zealando couldn’t say those consonants, it was part of the act.

In his 1992 memoir, Howard (ghost-written by John Costello), the singer explains that the “secret language” went further than chur, doy. He says that while socialising after a show one night, he and Merito were speaking in te reo to each other. “A woman in a group nearby said we were arrogant and rude for speaking Māori. We were so innocent – I’ll use that word rather than stupid – that we apologised. But as a direct consequence of that we started a language of our own.”

While “direct consequence” might be an exaggeration, the Quartet’s secret language became quite elaborate.

Morrison: “Her sounded like twer; so girls became twers. And the vocabulary was gradually expanded. If a woman was a nice person, we would say, ‘Sheed!’ Or not so nice, ‘Sheed not!’ Or ‘Heed’ and ‘Heed not’ in acknowledging fellas.

“No one would know what we meant because we’d just say it very casually. I might meet someone and want to know if I was liable to get into a conversation I’d rather avoid. I’d say to Gerry: ‘Woody be?’ And he might say: ‘Heed,’ meaning he’s all right. Or ‘Heed not!’ We had some rude ones; a ‘Finbar’ was some vulgar-type person. We could conduct a whole conversation in our slang.”

Younger musicians touring with them – especially Māori musicians – loved hearing the Quartet and Toni Williams use their language, and emulated them. Billy T James was a regular user, as were other members of the Māori showband fraternity.

Morrison recalled that during the This Is Your Life programme in 1989 that briefly reunited the Quartet, while on camera they automatically slipped back into their language. “One viewer wrote to the paper that her one big complaint about the programme was that she thought we were rude – she actually thought our showbiz lingo was Māori! Fancy, 30 years after we created our own lingo, we were getting ticked off again.”

To Jacobson, in 2008, Morrison said, “It’s nothing to be proud of,” but then demurred: “But maybe, if we are remembered for nothing else, we’ll be remembered for having our own language.”

Chur turns up regularly in online farewells to deceased musicians from their peers. And in the last couple of decades, the word is now used frequently outside of the music community. Piripi Walker, manager of Te Upoko O te Ika – the first iwi radio station, in Wellington – noticed that the hosts in the 1990s regularly used the word on air and with each other, usually as “chur, bro”.

And now Chur is in the Oxford English Dictionary, an example of how language continually evolves, and how not just te reo but also vernacular Māori expressions are entering and shaping Aotearoa English.

The word turns up regularly in AudioCulture profiles. John Dix describes how it was a core part of Ike Metekingi’s vocabulary, and in a 2014 interview with Steven Shaw, Bunny Walters said, “I never got a taste for soul music until I got up to Auckland and started mixing with musicians, the doys.

“Have you heard of that word before, doys? It’s a language that started out way back in show band days, with Māori show bands, Howard Morrison and others. They’d speak this alien language, like gibberish. Chur doy. You’ve heard that term? It goes right back, chur doy, it’s another language spoken by musicians back in the day. Only they could understand it. It was ‘elite’ communication between musicians.”

How it has become universal in recent years is yet to be pinpointed, but an anecdote expatriate drummer Stan Mitchell, formerly of The Drongos, told a US journalist in 2022, gives an idea of its currency. “It started amongst the musicians as a joke, and it really took on. Now it’s quite common. In fact, I was watching the Oscars a few years ago, and one guy got up from a film that was produced by Taika Waititi, a Māori guy who’s doing extremely well as a director. The actor looked down at Taika and said, ‘Chur!’ I nearly fell off my seat laughing.”

The week Sir Howard died in 2009, I ran into veteran guitarist Rob Winch who remembered that he once had to pick him up at the airport. Driving away, Morrison was on a mobile phone to an old mate. After his friend said hello, Morrison joked, “It’s Sir Doy to you!” Winch recalled, “I nearly drove off the road.”

--

Responses on AudioCulture’s Facebook page

Tuhi Timoti: Aww dright without the letter L. And “He’d” meaning he’s cool or. “She’d” meant she’s cool. “He’d not”: he’s uncool, and “She’d not”: she’s not attractive. Feen baa, a male; Feen twer, a female. The language is alive and still spoken today. Eddie Low, Brendan [Dugan], Gray [Bartlett]. Dean Ruscoe. Max Hohepa. The guys in Kairo. Young Howie. We could have a 10-minute conversation about someone in front of them and they’d have no idea we were discussing them Some of it in lurid detail. Lol … I speak that lingo better than I can speak Māori. Which is disgraceful.

Jonathan Woolf: I worked on the movie Don’t Let It Get You, in 1966, and can vouch for the “chur, doy” information. The movie was co-produced by Howard Morrison, and featured many members of the New Zealand pop scene at the time, starring the Quin-Tikis. On and off screen, the slightly distorted vowels-to-consonants words were in daily use, especially by Howard, and Rufus Herrick, Gerry Merito, and others. I recall one exchange that is in the film, ”All dright?” with the response "All dright!”