For Bruno, life was an adventure to some distant and unknown destination. An obituary first published in the NZ Listener, 1 July 1995, and revised in 2009.

--

It has been said that Bruno Lawrence made a living simply out of being himself. What is seldom acknowledged is how much determination and courage that took. In the 1950s, when the pubs closed at six and we sang ‘God Save The Queen’ at the cinema, anyone opting out of the nine-to-five routine was conspicuous, and usually marked as a troublemaker; certainly not nurtured as a potential cultural icon.

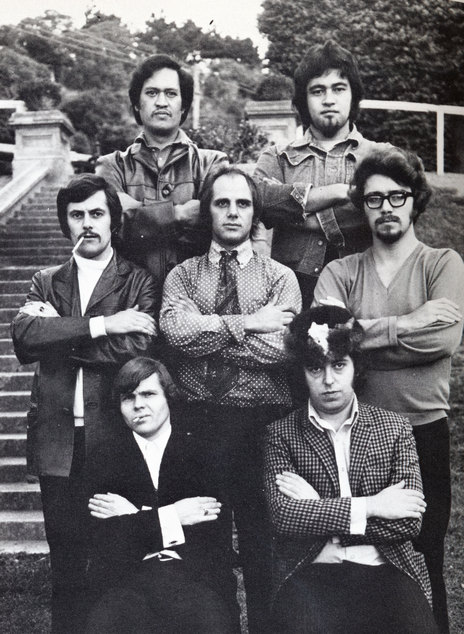

Bruno Lawrence, while in Blerta, c. 1972. - Alan Moon Collection

But if Bruno ever knew what conformity was, then he must have decided at an early age that it wasn’t for him. Jeanette McLaughlin, who later managed Carmen’s nightclub, the Balcony, was his classmate at primary school in Karori. There, he was known by his given name of David Charles Lawrence. “He was always laughing and always made other people laugh,” McLaughlin says. “He always did the opposite of what he was told to do, right through school. He was a leader, even then, for doing naughty things. Rebelling against society, which at that age you didn’t know you were doing, of course.”

By the time he left Wellington Boys College, Lawrence had discovered his passion for music, in particular the modern jazz of Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck and Thelonious Monk, and cobbled together his first drumkit.

After going to high school and losing contact, McLaughlin and Lawrence, now teenagers, ran into each other again on the ferry to Christchurch. “He was really trying to get into music, playing drums, and was going down there to see what was available. He had nowhere to stay, and we were staying with friends, so we helped him out for a night. And he’d forgotten to take his drumsticks! David had no money whatsoever, so we took him down the road and bought him a pair of used sticks.”

Back in Wellington, Lawrence found the music he loved could be heard and played in the netherworld of late-night coffee lounges, dancehalls and strip clubs. Bruno – as he had been nicknamed by friends at college – found a job at the Club Exotique, accompanying the strippers with drum rolls and fanfares.

He wound up playing all over New Zealand and Australia. He was widely regarded as one of the best, and his adaptability and musical sensitivity meant he worked with the top musicians in almost every field. He played jazz with Ricky May and Claude Papesch, cabaret with Jim McNaught and Tommy Adderley, pop with Max Merritt and Dinah Lee, Pacific country with Peter Posa. He travelled with talent quests and played on numerous TV shows. He played in pop groups such as The Measles (a short-lived answer to the Beatles) and even had a solo hit in 1965 (‘Bruno Do That Thing’).

Bruno - Bruno Do That Thing (HMV, 1965)

His drumming was dynamic and visceral. His crescendos would splinter sticks and bring cymbal stands crashing to the floor, while a ballad might find him caressing the skins with his bare hands.

Certain unforgettable incidents belied his real professionalism and enhanced his mistaken – yet persistent – reputation as some kind of musical hoon. In 1970, his song ‘Ride The Rain’, recorded by The Quincy Conserve, was a finalist in the Loxene Golden Disc Awards. Lawrence had recently been in hospital and a stand-in drummer was hired for the televised event. Producers, crew and musicians alike were appalled when Lawrence appeared unannounced, on crutches, to perform his song.

Medication, mixed with alcohol, had excited him. On screen he was maniacal, mugging behind the drum kit with an invisible pair of sticks. Offstage, after the event, he was worse, haranguing assorted local dignitaries with a rant about local musicians being undervalued. When the director-general of the NZBC attempted to calm him, Bruno held up one of his walking aids and invited him to “kiss my crutch”.

Bruno Lawrence (centre) in Quincy Conserve, 1970. Left to right, top to bottom: Rufus Rehu, Denys Mason, Johnny McCormick, Bruno Lawrence, Kevin Furey, Malcolm Hayman, Dave Orams.

That was it. Word went around that Bruno would never appear on television again. Yet within six months he would be back on screen, to collect a Feltex award for his first prominent acting role. As a musician in the NZBC docudrama Time Out, Bruno’s earthy presence had stood out among the “trained” actors that dominated homegrown TV drama. Even his voice was different: a deep, honey-coated growl, clear and articulate, yet with a raw, unapologetic Kiwi-ness that came to be instantly recognised, even off-screen.

Through the 60s he had become the centre of a loose cabal of like-minded bohemians that included Geoff Murphy – trumpet player, aspiring movie-maker, and Bruno’s future brother-in-law. Murphy began plotting films in which Lawrence would star, while Lawrence formed Blerta – a band/multi-media vehicle that incorporated film and live actors. Blerta (Bruno Lawrence’s Electric Revelation and Travelling Apparition) would satisfy their joint interest in jazz, as well as embracing the psychedelic rock that was becoming the soundtrack to the burgeoning hippie movement.

The Day-Glo apparition that was the Blerta bus became a symbol for Bruno’s philosophy that life was an adventure to some distant and unknown destination. Bruno was magnetic, and he picked up assorted creative spirits along the way. Musicians such as Fane Flaws and Patrick Bleakley, more than 10 years his junior, will testify that Lawrence taught them to play their instruments, even if his method of instruction could be harsh. Bass player Bleakley got used to the flying drumstick – pointed end first – behind the ear if he wasn’t playing what Bruno wanted to hear. One night during a torrid Flaws guitar solo, Bruno deliberately knocked a cymbal at an angle calculated to cut through the guitar’s lead, instantly silencing Flaws.

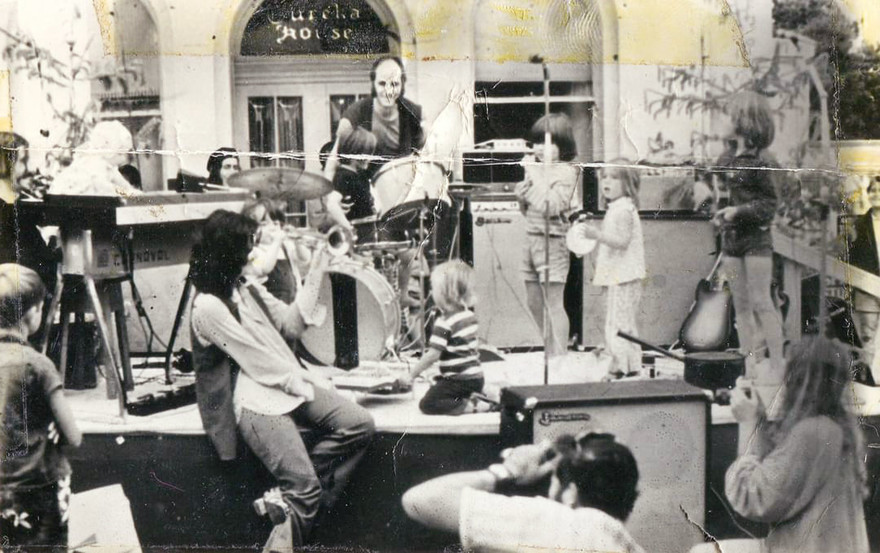

Blerta performing in Australia, Bruno Lawrence at the drum kit - Alan Moon Collection

Though music remained his first love, it was the movies that made Lawrence famous. Blerta’s use of film had amounted to little more than clever home movies, yet this was where Geoff Murphy honed his craft. Murphy’s early features, Goodbye Pork Pie and Utu, in which Bruno played major roles, coincided with the blossoming of the New Zealand film industry in the late 70s, and drew attention to Lawrence, at home and abroad. More screen roles followed, among them Smash Palace, Bridge To Nowhere, Beyond Reasonable Doubt, The Quiet Earth. In addition, there were ongoing TV appearances, from a cameo in the early NZBC drama series Pukemanu, to great Australian current affairs spoof Frontline.

Though he tended to be typecast as the rough-edged, laconic Kiwi bloke, the allegation that Bruno only ever really acted as himself is hotly disputed by Ian Watkin, fellow actor and sometime Blerta member. “He was an incredible perfectionist. He was particularly aware of his lack of grounding in theatre, and his response to that was to work harder at it. The art of it was revealed in the fact that people say it all came easy. It was the same in music. His image was that of the wild, free spirit. But I caught him, on numerous occasions, practising.”

In a sense, his acting and musicianship drew on the same skills. As an actor, his ability to listen and respond to others, not to mention his acute awareness of rhythm and timing, were refined through years of jazz improvisation.

Bruno’s tangi took place on Wednesday, 14 June 1995, at the Taupunga Marae, just up the road from Snoring Waters, the home in the tiny Hawke’s Bay town of Waimarama purchased in the mid-1970s by members of the Blerta clan. In recent years, most had moved away, leaving just Lawrence and his wife Veronica, any number of their five children, and the occasional grandchild.

Like a Blerta gig, the tangi was an unorthodox mixture of traditions. Māori, Pakeha, Ratana, Catholic and probably pagan rituals clashed happily, for once, presided over by an old jazz pal from the 50s, Ronnie Smith, now a Ratana priest.

As the numbers on the marae grew, it became apparent just how many people Bruno had touched over the years, and how varied. Sam Neill, now a Hollywood star, read a tribute from John Clarke; nearby, a man was identified to me as a reformed safe-cracker – “a very good one”.

Finally, Bruno was lifted high in the coffin that Fane Flaws had covered with painted illustrations, and a procession followed it down the dirt road to the marae’s cemetery. Bruno is the first non-tribal member to be buried there. Strains of Pavarotti’s recording of ‘Ave Maria’ mingled with the jazz saxophone of Jonathan Crayford, who followed the coffin blowing his horn, New Orleans-style.

Back at the marae there were stories, there were tears, and, of course, there was music. Many of New Zealand’s best musicians over the last 40 years took part – but they sure could have used a drummer.

--

Listen: ‘Bruno Do That Thing’ (HMV NZ, 1965)

--