NEW ORLEANS, April, 1992 – “I’ll give you a quote for your magazine.” Cyril Neville puts his arm around me. He has a broad grin on his face, which is framed in dreadlocks. He’s dressed in a purple robe, with a cap encrusted in sequins to read “N”.

“Why isn’t more Māori music played on the radio in New Zealand?”

Moana with Cyril and Charles Neville of the Neville Brothers, outside Tipitina's, New Orleans, April 1992. - Photo Chris Bourke

Cyril is the political Neville, the raving rastaman who makes rappers look inarticulate. He’s standing on the corner of Tchoupitoulas and Napoleon, outside Tipitina’s, the small club in uptown New Orleans, just a few metres from the Mississippi River. The Neville Brothers grew up near here and return to play at Tip’s every few months. Tonight, they’re on the bill with Moana and the Moahunters as the support act.

Cyril is the one who invited the Moahunters to play the celebrated Jazz & Heritage Festival and share a few gigs with the Neville Brothers and his own band, the Uptown Allstars.

The invitation came after the Neville Brothers, at their lowest ebb, were welcomed on to a South Auckland marae during the visit to New Zealand last October. The band was at the end of a world tour; Aaron was in a wheelchair, having pinched a sciatic nerve. Mixing with the bros from South Auckland, the brothers thought they were home already.

“It felt like I’d been there before – I was part of the family,” Aaron Neville says. He’s blocking the sun in a doorway at Tipitina’s, wearing a bulging denim jacket embroidered with a large “A”.

“Everybody was just overwhelmed,” says his brother Charles, the suave saxophonist. “We felt like we were being welcomed home.”

Moana Maniapoto outside the legendary venue Tipitina's, New Orleans, 1992. - Photo Chris Bourke

On Tchoupitoulas Street, a few blocks from the Nevilles’ home turf, it’s very apparent this is their home. As Moana conducts a TV interview with Cyril and Charles, people cruise by in large, large motors. “Heeey, Neville Brothers!” they cry. Cyril’s family sit in a late model station wagon, waiting for their father to stop talking. Elder brother Art Neville (Dr Funk) is inside the club, complaining about the new graffiti in the dressing room. Aaron has disappeared and Charles ... Charles just waits for Cyril to stop talking.

The Neville Brothers have just welcomed Moana, the Moahunters, their relatives and a New Zealand film crew to their whānau. The launch for the Brothers’ new album, Family Groove, got lost in all the ceremonies.

The welcome began the day before, at the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport. The Soul Rebels brass band fanfared the Moahunters’ exit from the plane.

“It was outrageous, like being in a dream,” says Moana. “They were raging already and the first thing I saw was Aaron’s great hulking form, dancing away. And all the other Nevilles, waiting for us. Far out!”

That night, there was a party at the home of the Nevilles’ business manager. Tables were laid with candies and every Louisianan dish imaginable and the Soul Rebels came blasting out of the house with Art Neville following, waving a Mardi Gras umbrella.

“He’s pretty funky, old Art,” says Willie Jackson, the Moahunters’ manager.

Memories return of the Neville’s emotional farewell party after their Auckland concert last year. Charles saying goodbye to a group of Māori women from the marae. Cyril saying hello to someone from Greenpeace. Aaron in acute pain, sitting stiffly in his chair. And Art being introduced to Murray Cammick as Rip It Up magazine’s editor. “Rip It Up? Rip It Up?” he cried, bursting into song. ‘Saturday night and I just got paid ...’ I was on all those Little Richard records.”

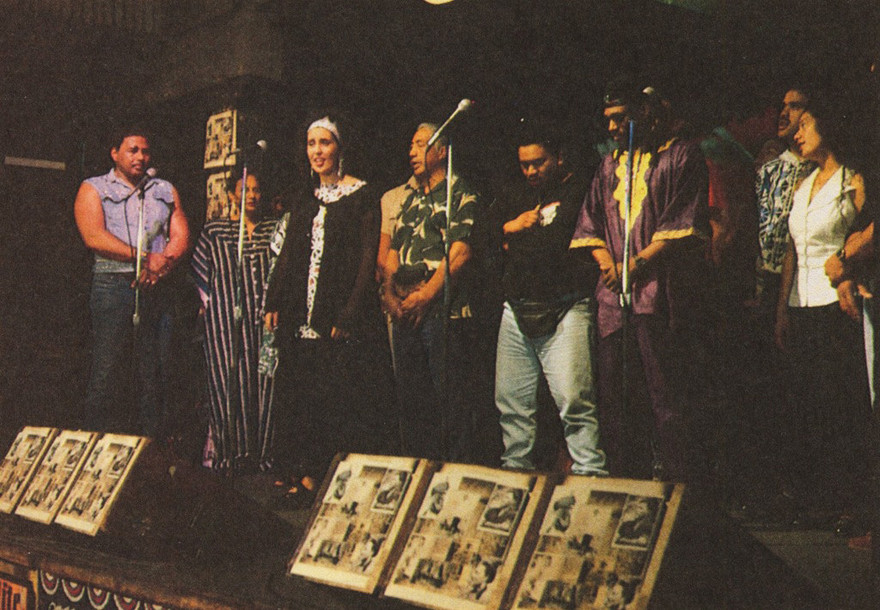

Moana, the Moahunters and the Nevilles, on stage at Tipitina’s, New Orleans, April 1992. - Photo Nick Bollinger

THE TIPITINA’S welcome began with an African dance troupe, drumming, chanting and leaping their way into the club. Then Cyril took the stage:

“We welcome today not only our friends, but our extended family from New Zealand – Ao-tea-roa. The Māori people. We’re trying to duplicate here what happened when we went there. We were welcomed into their families, into their homes, their society.”

Then the brothers produced gifts, each one a personal gesture. From T-shirt collector Art came a bundle of the Nevilles’ classic shirts; from Aaron, carved figurines; from Charles, screen prints of a painting he had done, and from Cyril, political texts that look well read and annotated.

“I learnt so much about their culture from them, and so much about myself,” said Cyril. “So I offer them knowledge of me and my people in these books ... we have some of all our bloods running through each other, so we may as well get it straight and be one family: the family of maaan.”

Moana’s uncle responded with a speech in Māori and English saying what an honour it was to be among the “big guns” of the music world.

“I’ll be a hero when I get back! As it is now, I’m just a nobody. But it doesn’t worry me. We’re all here together, as one people.”

Then Willie, telling the audience of assorted Nevilles, hangers-on, TV crews and international press, about life in South Auckland. Crime, unemployment – Māori are the leaders in all areas, he said.

“The stresses and problems just to survive are great. So when the Brothers came to South Auckland it gave our people the opportunity to relax, to sit back and know that if there’s nothing else in this world, there’s music – something that bonds us all.

“When the Brothers came to South Auckland, the last thing in our minds was a gig at Tipitina’s, or at the the New Orleans Jazz Festival. Well, most of our guys hadn’t been out of South Auckland, let alone past Australia to America. What brought us here was the bond we achieved in New Zealand. If the Brothers had said, just come over to our houses and we’ll have a jam, we would have organised the same way we did. Because a special relationship has been set up, something that will stay in our hearts forever. So the album is aptly named Family Business.”

The Moahunters, their family and the Māori TV crew then all sang ‘Whakaaria Mai’. The Nevilles join in with the English words (‘How Great Thou Art’), just as they do on their new album: on the closing track the Brothers are overdubbed on a location recording of the Moahunters singing the song to them at the Mangere marae.

At Tipitina’s, after the bands’ duet on ‘Whakaaria Mai’, there is a New Orleans feast. Tucking into jambalaya, chicken gumbo and bean hash, Willie Jackson is well chuffed. “I just sang on the same stage as Aaron Neville!” he says.

That night 1000 people were jam-packed into Tipitina’s, which is about as flash as a woolshed. And when a Māori warrior took the stage, with moko and fierce eyes, shouting the wero, they listened. And they stuck with it as the Moahunters came on with their unique mix of traditional Māori music, funk, pop, poi and politics. The audience, full of listeners waiting for one of the world’s greatest live bands, was won over. It happened again through the week, at the Moahunters’ gigs with Cyril Neville and his fiery Uptown Allstars, and on the exotic Congo Square stage at the jazz festival.

Rip It Up, June 1992.

LIKE FATS DOMINO, the Moahunters would have walked to New Orleans if they had to. Every government agency, funding body and corportate sponsor turned them down, not seeing the significance of the visit. Rich men’s yachts, orchestras to Expo, no problem. Māori pop music? Forget it. The only support the band got was from grassroots people, their family and friends – and from Crowded House, who put on a free concert for the band which raised $3500.

“People might think, ‘Oh you just got invited because of the pōwhiri at Mangere’,” says Willie. “But Cyril and Aaron would never have invited our band if they didn’t think they were up to scratch. They watched the band very closely in Auckland. And in New Orleans, Cyril had advertised and he’d said to all his mates, ‘I’m telling you, these guys are family.’ They were sitting at the side of the stage, connoisseurs of funk.

“But people from the music industry ask, ‘So – did you get a record deal?’ That wasn’t the be-all and end-all of the trip. We went across to meet our friends, and also to get our band inspired at the Jazzfest. And we achieved everything we wanted to achieve. There may be the possibilities of a deal, we met with a few different record people. You never know.”

And in New York, Moana and Willie had a lengthy meeting with an expensive entertainment lawyer – attorney to David Byrne, Cyndi Lauper and the Jazzfest – who had taken a fancy to them. His office was on Park Avenue, with rejection letters for ‘Girls Just Wanna Have Fun’ on the wall. He charges $1000 for 10 minutes, but talked to the Moahunters for two and a half hours. “We can’t pay you,” they said. “Who mentioned money?” replied the attorney, inviting his partners in to watch their videos (the ones that can’t get played on New Zealand television).

The Moahunters couldn’t believe they were on their way until they were on the plane. And when they got there, “They just couldn’t believe it,” says Willie. “To see the calibre of musicians.” But they could cut it there; they found when they got up to jam that to the Americans, there was something unique about South Auckland funk.

“For me it just confirms that a lot of our Māori musicians are right up to their standard,” says Willie. “Here, there are no role models – no funk role models. In New Zealand they’re probably the best in the business, but there’s no one they can compare themselves to. And then to go across to America and they know they’re on the right track. They see the Neville Brothers, the Uptown Allstars – they’re great players, those guys, but not that much better than our guys.”

Moana is more down to earth: “At one stage the band got a little bit down, after a performance we didn’t think was that good. We were comparing ourselves to the only two bands we’d really related with in New Orleans and then thought, hang on – we’re talking about the Neville Brothers and the Uptown Allstars. Why get depressed because we don’t think we’re up to their standard?

In the United States, the Moahunters found there was something unique about South Auckland funk.

“But given the lack of support we got to get over there – the struggle for funding, the music awards thing, etcetera – you think, ‘God, don’t people take Māori music seriously?’ And then to go over there and see the response that it gets and the respect. And that Cyril Neville and his Uptown Allstars are doing exactly the same sort of thing we are, fusing the traditional with the modern. They’ve got their Mandinka maidens on stage and the people just go ape over it.”

Simon Lynch, keyboardist with the Moahunters, says, “A lot of people came up and said they’d never heard funk played that way before. ‘You guys have definitely got your own sound.’ We got a great reaction. It felt very good. I knew we were different. If we were trying to copy the style of any of the New Orleans bands we would have ended up on our face. We had our own style. Full credit to Moana for developing that style and sticking to what she believes in. For the band, it peaked at the festival. It felt very privileged to play there – here’s us, in some very illustrious company. But we justified ourselves.

“The main thing was how proud New Orleans people are of their music. That just got to me. I thought, why can’t we be like that? Here, it’s a very oppressive environment to be making original music in. You’ve got people who look down on New Zealand music. They should look up to it. In New Orleans, if you’re a musician, you have some respect, whereas here ...”

For many who went, a favourite moment was backstage at Tipitina’s. The Neville Brothers are kicking back on their turf, and so are the Moahunters. Lynch describes the scene: “In walks Eric Clapton, Nathan East – Stevie Wonder’s bass player – and that annoying percussionist who used to play with Elton John. All the guys from the Moahunters say, Wow! And Aaron and Cyril are sitting there, like, ignoring them. And Willie says, ‘That’s Eric Clapton over there – aren’t you gonna go and speak to him?’

“And quite within earshot of Eric Clapton, Cyril says, ‘Hey man – in this town, he comes and speaks to us’.”

--

First published in Rip It Up, June 1992.